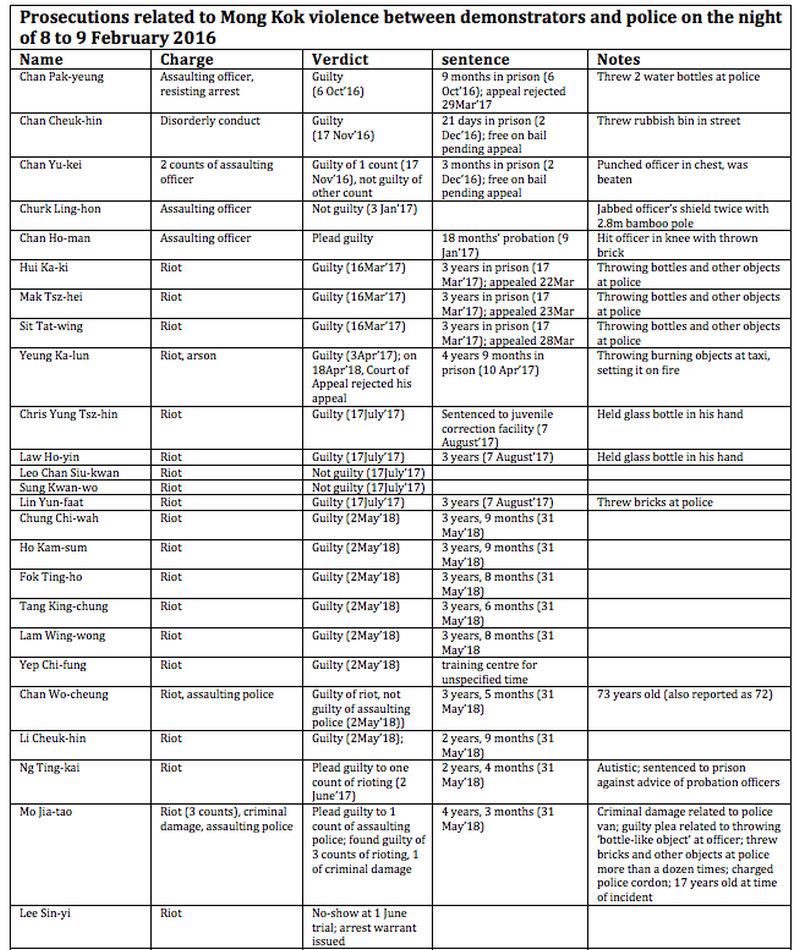

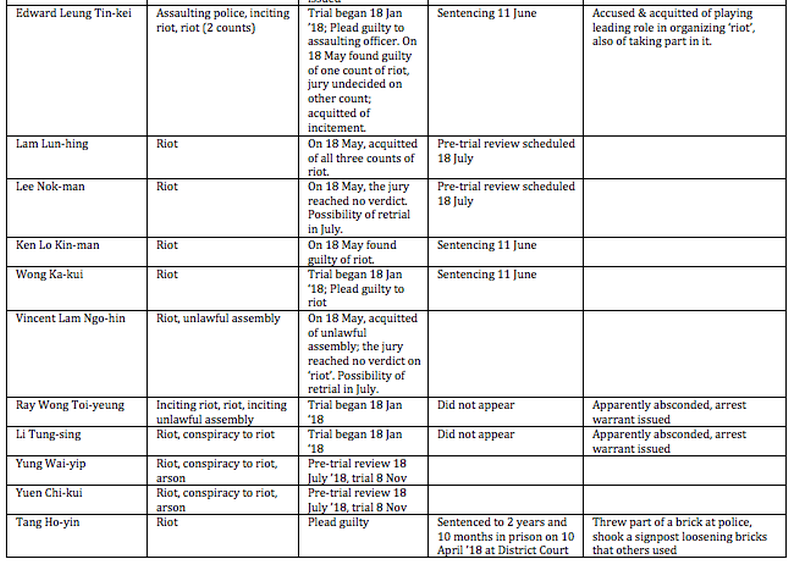

On Monday, June 11, Edward Leung, Lo Kin-man and Wong Ka-kui were sentenced to, respectively, six years, seven years, and three years and six months in prison, following their conviction for ‘riot’. Leung had previously plead guilty to assaulting a police officer in the same case.

The six-year and seven-year sentences are the longest yet out of the 25 related to the police-protester violence in Mong Kok on the night of 8 to 9 February 2016. Cumulatively, the 25 defendants have been sentenced to 71 years, 1 month and 21 days in prison, 18 of those for ‘riot’ amounting to 67 years and 6 months.

On Thursday, May 31, in the largest ‘riot’ trial, a judge sentenced nine of ten defendants to prison. The heaviest sentence of four years and three months was given to Mo Jia-tao, who was 17, a minor, at the time of the incident. A 73-year-old (also reported to be 72) was sentenced to three years and five months, and an autistic man got two years and four months. This last sentence was imposed against the advice of probation officers. The nine were sentenced to overall 31 years and one month in prison.

With these sentences, most of the trials related to that night of violence in 2016 have concluded. Three defendants, including Leung, will be retried on counts on which the jury could not reach a verdict, and two defendants will go on trial in November. This, therefore, is a good moment to step back and analyze what has occurred.

Why ‘riot’ is, in this case, a loaded term

The event to which these trials are related has been variously referred to as a ‘riot’, the ‘Fishball Revolution’, ‘clashes’ and ‘civil unrest’. I find ‘police-protester violence’ or ‘clashes’ to be the most appropriate terms.

The term ‘riot’ was politicized by the Hong Kong government immediately after the event. It used this designation to stamp its definitive judgement on the event, to block calls for an independent inquiry into police actions on the night and to stigmatize the protesters, effectively declaring that the police were entirely in the right, the protesters entirely in the wrong.

Riots occurred in Hong Kong in 1956, 1966 and 1967, and in each case the government conducted an inquiry and published a report. The government has refused to do so in relation to 2016. The term ‘riot’ was quickly adopted by pro-Communist Hong Kong media.

‘Riot’ is a specific offence in the Hong Kong Crimes Ordinance, and using the term may imply the view that those who participated are liable to prosecution for that offence. ‘Riot’ also has the connotation of out-of-control violence involving destruction of property, but in fact, virtually all of the protester violence targeted police.

There was no looting, there was minimal destruction of private property, and there was almost no targeting of private property. Only one protester was charged with arson, for setting a taxi on fire. For these reasons, the term ‘riot’ is misleading, simplistic, politically biased and best avoided.

‘Fishball Revolution’ is a term that tends to be used by supporters of the protesters, sometimes ironically. It refers to the fact that the protesters originally came out that night to support hawkers who were accosted by Food and Environmental Hygiene Department officers and police officers (and who may or may not have been selling fishballs). The term is hyperbolic: whatever occurred that night, a revolution it was not.

‘Unrest’ seems a bit abstract and distant for what after all was a discrete event occurring over the course of a single night. ‘Police-protester violence’ or ‘clashes’ puts the focus most squarely on what most definitely occurred: a night-long fight between police and protesters.

The trial of Edward Leung

The just-concluded trial was the highest profile Mong Kok case because one of the six defendants was Edward Leung Tin-kei. At the time of the clashes, Leung was a leader of localist group Hong Kong Indigenous. He then ran for the Legislative Council in a by-election held the same month, February 2016.

While finishing third, he did so well that he was expected to win a seat in the city-wide Legco elections of September. But he was disqualified from running by an administrative official at the behest of the Hong Kong government, on grounds that since he supported independence for Hong Kong, he could not be expected to uphold the Basic Law, a duty of Legco members.

He had been allowed to run seven months previously and, in his application for candidacy, had forsworn independence advocacy and promised to uphold the Basic Law. To protest this abuse of his rights, he filed an election petition at the Hong Kong High Court, which to this day, a year and a half later, still has not been heard.

Not only is Leung probably the best-known localist leader in Hong Kong, he was also charged with “inciting riot”, the first person to stand trial for that offence. In effect, the Hong Kong government was alleging that he was one of the main instigators behind the “riot”. His fellow leader of Hong Kong Indigenous, Ray Wong Toi-yeung, was also charged with “inciting riot”, but he has absconded, whereabouts unknown, and a warrant has been issued for his arrest.

‘Inciting riot’ was only one of the charges Leung faced. The others were two counts of riot and a count of assaulting a police officer. He pleaded guilty to the latter charge, was found guilty of one count of ‘riot’, and the jury failed to reach a verdict on the other count. He was acquitted of ‘inciting riot’. The government has since announced that it will re-try Leung on the one riot count.

There were originally ten charged in this trial. As well as Wong, one other, Li Tung-sing, absconded. Two who are charged with ‘conspiracy to riot’ as well as ‘riot’, Yung Wai-yip and Yuen Chi-Kui, will be tried separately in a trial scheduled to begin on November 8.

Of the five others tried with Leung, Wong Ka-kui pleaded guilty to riot; Lo Kin-man was found guilty of riot; Lam Lun-hing was acquitted of three counts of riot; the jury reached no verdict in the ‘riot’ charges against Lee Nok-man and Lam Ngo-hin; Lam Ngo-hin was acquitted of unlawful assembly.

So of the 12 counts brought against the six defendants in the case, only four resulted in conviction and Leung was acquitted of the most serious charge against him, incitement. Indeed, the government has thus far failed to get any conviction related to ‘inciting’ or organizing the protest. While the sentences of seven, six and three years four months are shockingly heavy, this trial was by far the worst result yet for the Hong Kong government in its three dozen or so prosecutions related to the Mong Kok police-protester violence.

The only clear difference between this case and the others was that it was held in the High Court with a jury, whereas judges issued the verdicts in the other trials. Was the government’s case worse, or does the result also indicate that juries tend to be more sceptical than judges, at least when it comes to ‘riot’ charges?

By contrast, the May 31 sentencing of ten concluded the government’s most successful case against Mong Kok defendants, with all ten convicted and sentenced to heavy prison terms.

An overview and analysis of results

Originally, 90 people were arrested, and 51 were charged. Charges were dropped against 20 due to lack of evidence, leaving 31 to prosecute. Six were later arrested or charged with additional counts.

Of the 31 trials completed so far, 25 defendants have been convicted on 34 counts. These include 21 for ‘riot’, one for arson, five for assaulting a police officer, one for disorderly conduct, one for resisting arrest, and two for criminal damage. Eight defendants have been acquitted on ten counts. These comprised five for ‘riot’, three for assaulting an officer, one for unlawful assembly, and one for ‘inciting riot’. In addition, a jury reached no verdict on three counts.

That’s a 75 percent conviction rate, compared with about 50 percent for all criminal prosecutions, and about 40 percent for Umbrella Movement-related prosecutions. Looking just at prosecutions on ‘riot’ charges, 21 out of 26, or 80 percent, have resulted in convictions.

Sentences for the 25 sentenced so far have been harsh. Only one conviction has resulted in a non-custodial sentence. All others were sentenced to prison, with the shortest sentence being 21 days and the longest seven years. Of the 18 defendants convicted of ‘riot’, one was sentenced to seven years, one to six years, two to four-to-five years, six to three-to-four years, five to three-year terms, three to two-to-three years, one to a training centre and another to juvenile detention.

By comparison, only five demonstrators out of approximately 100 convicted after the Umbrella Movement got prison sentences, and these amounted to a total of 20 months. Eight police officers were sentenced to a total of 14 years and three months in prison for Umbrella Movement-related offences.

From this, it can be concluded that Hong Kong judges take a very dim view of protester violence, dimmer than in the past. The average prison term for those convicted of ‘riot’ is 3.75 years. The 1956 riots were much more serious, resulting in 59 deaths, but prison sentences for ‘riot’ ranged from seven months to two years.

In many of the cases, the violence committed by the defendants seemed not terribly serious. Among those convicted of ‘riot’ and sentenced to three years in prison, three threw bottles and other objects at police, one held a glass bottle in his hand, and one threw bricks at police.

One of the longest sentences, four years and nine months, was for ‘riot’ and arson. It involved throwing burning objects at a taxi and setting it on fire. One of the shortest ‘riot’ sentences — two years and 10 months — was for throwing part of a brick at police and shaking a signpost so as to loosen bricks in the pavement that could be used by others.

It also appears that judges have made a big distinction between merely committing violence and doing so as part of a riot. This can be seen by comparing sentences for violent offences but not riot with those for ‘riot’, which is defined as ‘a breach of the peace’ in an unlawful assembly. (Public Order Ordinance, Cap 245, Part IV, article 19)

Four defendants were convicted of violent offences such as assaulting an officer, and received sentences totaling one year and 21 days. One defendant threw two water bottles at police. Another threw a rubbish bin in the street. Yet another punched an officer in the chest. And the fourth hit an officer in the knee with a thrown brick.

It is unclear why those prosecuted for committing violent offenses at Mong Kok were not charged with ‘riot’ like the others. As noted, those convicted of ‘riot’ got on average of 3.75 years in prison each.

Based on this comparison, it seems that the harsh sentences for ‘riot’ have as much if not more to do with being present at an unlawful assembly where a breach of the peace has been committed as with any act of violence perpetrated by the defendant.

The Public Order Ordinance needs reform but the Hong Kong government is doubling down on its use.

This raises many questions about the legitimacy of the ‘riot’ charge, which comes under the Public Order Ordinance, which has been repeatedly criticized by the United Nations Human Rights Committee, Human Rights Watch, Hong Kong Watch and former Hong Kong governor Chris Patten as failing to meet international standards, facilitating excessive restrictions on freedom of assembly, and being open to abuse by police and prosecutors.

In regard to ‘riot’, the bar is set very low, for all that needs to have occurred is commission of a ‘breach of the peace’ at an unlawful assembly. A breach of the peace could be as little as shouting loudly; there may be no violence involved.

Many pro-democracy demonstrators have also been convicted under the POO, and 13 have received lengthy prison terms (12 to 13 months and one to eight months) for the nonviolent offence of unlawful assembly. Their appeal of the sentences will be heard in September. See the #NENT13 case here.)

If there is evidence the defendant has committed a recognizable criminal offense, he should be tried for that act, and not for acts committed by others which the defendant had nothing to do with. In the specific cases of the Mong Kok police-protester violence prosecutions, while a protester may be charged with, for example, assault for throwing bricks or water bottles, it is much more problematic to charge the same protester with ‘riot’.

In the May 31 sentencing hearing, the judge said the ten defendants bore ‘collective liability’ for the riot on top of what each of them had done individually. This is a troubling concept, especially as none were convicted of ‘inciting riot’ or organizing it, and no evidence was introduced that they were coordinating their actions or conspiring to ‘riot’.

While numerous human rights experts have pointed out that it is more than high time for the POO to be reformed, the Hong Kong government is instead increasing its use in prosecuting demonstrators.

The lack of police accountability for actions during the Umbrella Movement has been compounded by a similar lack in the Mong Kok police-protester violence.

The Mong Kok ‘riot’ trials should be viewed in the wider context of the event to which they are related and this particular moment in Hong Kong history. The violence between Hong Kong police and citizens that night was the worst since 1967. For the first time in living memory, a police officer fired his pistol at a protest, bringing Hong Kong closer than ever to its first protest-related fatality since the 1960s.

In light of its magnitude and gravity — something about which there was wide consensus in Hong Kong society across the political spectrum — the Hong Kong government should have called for an independent inquiry to determine just what happened, who was to blame, and what the underlying causes were. Instead it immediately brushed off the suggestion, rejecting calls for an inquiry less than a week after the event.

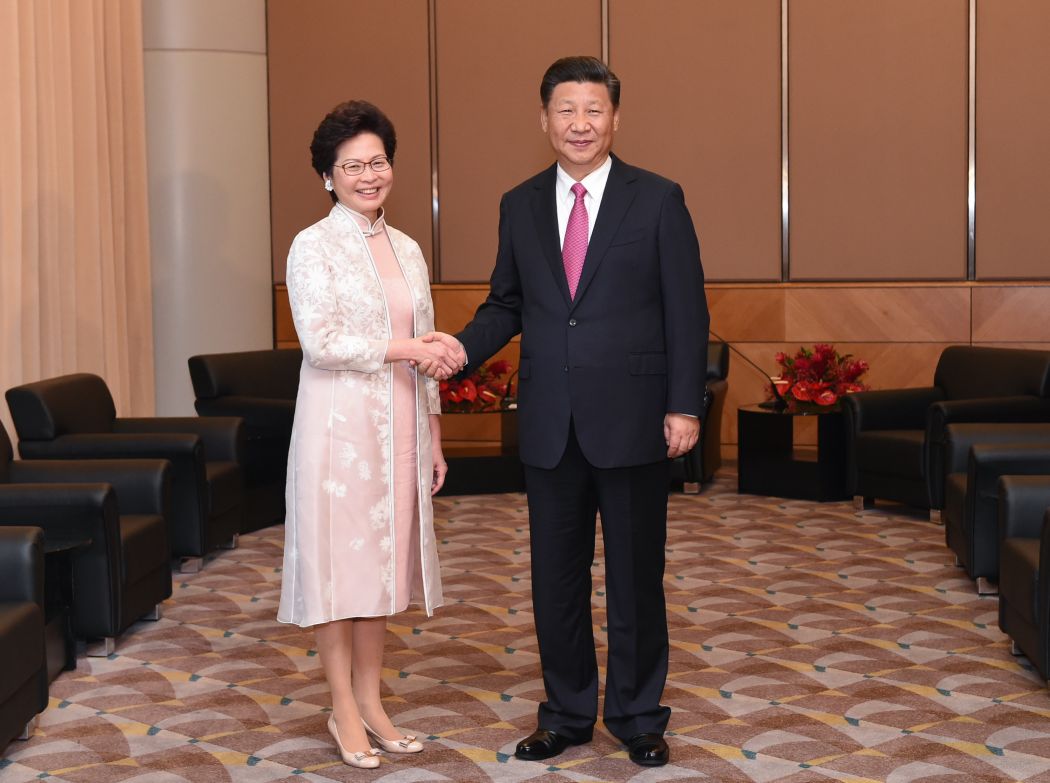

It was determined from the start to label the events a ‘riot’, to place all blame on the protesters and shield the police and government officials from accountability. Chief Executive Carrie Lam recently reiterated the government’s refusal to sanction an independent investigation.

This is in contrast with not only previous Hong Kong government inquiries into the riots of 1956, 1966 and 1967, as mentioned above, but also, for example, the inquiry into the riots in England in 2011 by an independent panel set up by the government.

Hong Kong actually has a Commission of Inquiry Ordinance. Recent commissions looked into the fatal ferry accident of 2012 and lead found in drinking water in 2015. Was the police-protester violence of 2016 not as important as those matters, and of just as much public interest?

Just to take a single example of the consequences of this refusal to get to the bottom of what happened: in the case of the police officer who fired two shots into the air, the police said they would conduct an investigation. Then, a few days later, the police concluded the officer was justified, as he believed he was defending imperiled colleagues.

Later, the officer was presented with an official commendation. This process ridicules the whole notion of a proper impartial investigation and could actually have the effect of encouraging police officers to use firearms at demonstrations.

Apart from the question of whether or not the officer was justified in firing his gun, other important relevant questions would include:

- How did it ever get to the point that the officer apparently felt he had no other recourse than to fire his gun into the air in one of the most densely populated parts of the city?

- How had the police allowed the situation to get so out of control that by that point the officer apparently believed his colleagues to be in real danger? Does that not reflect poorly on how the police handled the occasion?

- If so, what did the police do wrong; how could they have handled it better? Did the police take appropriate crowd control measures? Did they handle the demonstrators in an unjustifiably aggressive or provocative manner?

- Did they do enough to protect the rights of all involved? What are the guidelines for use of live fire, in particular at demonstrations, and do they need to be revisited and perhaps revised? The police say they have such guidelines, but they refuse to divulge them to the public or even to Legco members, rendering public oversight impossible.

- What had motivated the protesters to, in some cases, attack police, given that the original “spark”, FEHD and police officers trying to prevent hawkers from selling their wares, doesn’t seem sufficient motivation? Many defendants have testified that their primary motivation was anger at the police for violence inflicted upon demonstrators at the Umbrella Movement. This does seem to be a widespread sentiment, and, if so, how should that affect police policy regarding policing of demonstrations? Does it reflect a need for greater police accountability, and if so, how can that be achieved?

It is astounding that in one of the more important events to have occurred in the last few years in the city, the government has decided not to look deeper into the matter and try to get to the bottom of it. Instead, it simply labels the incident a ‘riot’, cracks down on the ‘rioters’ through prosecutions, and moves on as if everything else is fine.

The Hong Kong government has attempted to draw the attention of the media and the people away from these questions and issues by the long parade of prosecutions. And to a large extent, this seems to have succeeded. It played on the accurate view that a large number of Hong Kong people, including myself, deplore violence, and distracted people from the high probability that the police were at least as responsible for the violence as the protesters.

So whenever we discuss the prosecutions related to that night’s events, we should always remember the context, the many unanswered questions, and the fact that an unelected government has shielded itself and the police force from any form of accountability.

As for what actually happened that night, the account that Edward Leung gave when taking the stand in his own defence at his trial is close to that which circulates widely in opposition circles: FEHD officers approached hawkers in Mong Kok and demanded that they stop selling because they had no licences.

It was unclear why they felt the need to enforce the law so aggressively that evening, since Chinese New Year has traditionally been a time when grey areas in the law were winked at, and the previous year the FEHD took no such action. Some people hawk traditional foods at that time of year and no other. They are unlikely to go through the long, arduous procedures needed to obtain a hawking licence.

Through social media, calls went out to come and defend the hawkers. This role had been performed by Hong Kong Indigenous and other groups the year before as well, and that time, the holiday passed without major conflict, even though it was closer to the Umbrella Movement than 2016 was.

As demonstrators gathered, FEHD officials called in the police for back-up. The police acted in an aggressive manner, similar to that employed to clear the Mong Kok occupation during the Umbrella Movement in November 2014 and to keep the streets of Mong Kok clear of demonstrators in the aftermath.

That involved using significant and unjustifiable force such as the systematic aiming of batons at demonstrators’ heads. But at Chinese New Year 2016, police were unprepared for the eventuality that demonstrators might stand up to their aggressive behavior, and the situation quickly escalated to physical confrontation.

If nothing else, the policing that evening appears ham-handed and not very well attuned to the situation. The lesson the police had learned from the Umbrella Movement clearance of the Mong Kok occupation was that it was important to be uniformly and consistently tough on demonstrators, to send them a clear message of what would be tolerated and what not.

At the time of the Umbrella Movement and the Mong Kok “gao wu” demonstrations in the aftermath of the Mong Kok occupation, police had sufficient numbers on the streets to employ that strategy, but they did not on the evening in question. They simply assumed the demonstrators would be cowed and disperse, and when they did not, the police had no back-up plan.

Beyond that, it is important to remember that there has been no accountability for police actions during the Umbrella Movement either. There again, as with the Mong Kok violence, there were calls for an independent investigation into police actions; in particular, the eight-hour-long tear gas attacks on unarmed, nonviolent Hong Kong citizens on 28 September 2014, which were arguably the number one trigger of the Umbrella Movement, as Hong Kong people rose up in outrage.

To this day, the only information we have from police about the decision-making and the command responsibility for that action is an interview given to South China Morning Post by an anonymous police superintendent saying it was entirely his responsibility.

This account is hardly credible, falling far short of addressing the matter. I don’t believe for a second he was solely responsible for ordering the initial attacks, but even if that were the case, he certainly couldn’t have ordered all on his own that the tear gas attacks continue for eight hours.

Throughout the Umbrella Movement, on numerous occasions, the police used force disproportionately, including in the clearance of Mong Kok. I can still very clearly hear in my memory the loud haunting, sickening THWACK! of police batons landing first on the umbrellas and then on the hardhats of demonstrators who were sitting in front of police lines.

Later, police would say that the fact that demonstrators came ‘armed’ with protective devices such as umbrellas (against pepperspray) and hardhats (against baton blows) was a sign they intended trouble. No, it was a sign they simply intended to protect themselves from the police violence they knew full well to expect, violence that was endorsed and in all likelihood ordered by the government.

The lack of police accountability for actions during the Umbrella Movement left festering wounds which were an important precipitator of protester actions on the night of the Mong Kok clashes. People remember. And now, the lack of investigation of police actions during the Umbrella Movement is followed by lack of investigation of police actions in Mong Kok that night.

People remember all of this as well. The wounds do not go away but fester. Langston Hughes’ famous poem, written about African-Americans’ struggle for equal rights in the U.S., comes to mind:

In the newspaper, I read that the police themselves say that relations with Hong Kong people have now recovered since the Umbrella Movement, and I just have to laugh: Who are they kidding? Police refer to a survey they supposedly commissioned in January this year as evidence, but that survey, if it does exist, is not publicly available.

We do, though have HKUPOP’s regular survey on the popularity of Hong Kong disciplinary forces and the Hong Kong PLA Garrison, the most recent of which was conducted in December 2017. It shows very little change in police unpopularity from November 2015 (about a year after the Umbrella Movement).

The police are still the second most unpopular disciplinary force out of ten. The only one that does worse is the PLA Garrison, which is not a disciplinary but an occupying force. Indeed, that the police do only slightly better than the PLA should tell you something. They have a “satisfaction rating” of 64.1 versus the PLA’s 63.3. And that 64.1 has gone up less than two points from the 62.4 of November 2015. Instead of complacency, this should give cause for concern.

And rather than a blossoming love fest between the police and the people of Hong Kong, what has occurred is that official Hong Kong — the Hong Kong of the unelected government and the unaccountable police force, the Hong Kong of the continued, indefinite denial of the promise of universal suffrage — continues down one path.

And the Hong Kong of a good many of its people, who want justice, democracy and real autonomy, who want a government and a police force that recognize they work for the people and should implement the people’s will rather than regard them as underlings to be “policed”, continues down another path.

The paths are diverging ever further apart. What becomes of that widening gap remains to be seen, but it is politically unsustainable and will probably lead to increased repression.

The police force’s lesson from the Umbrella Movement and the Mong Kok clashes is to be tougher on demonstrators. So it has invested tens of millions of dollars in new water cannon vehicles, the first of which has just been delivered. I doubt many Hong Kong people are thinking, Just what we need!

The government’s lesson is that it has to be harder on the pro-democracy movement and all political opposition, resulting in the most widespread crackdown since the handover, in the form of dozens of prosecutions, disqualifications from Legco, and barring of candidates from running for office on political grounds, among other means.

The people’s lesson is that there is no justice in Hong Kong under Communist rule.

It is true that eight police officers were eventually tried and convicted for assaulting demonstrators in the Umbrella Movement. And it is true that those eight officers were sentenced to more prison time than all Umbrella Movement protesters put together. But it is as if the government and police are using the prosecutions related to the Mong Kok clashes to take revenge.

The prosecutions of those officers came about against the will of the police force, which tried to prevent them from occurring. The officers were only prosecuted after tireless efforts of activists in pursuit of justice. What all eight officers had in common was that they were caught on video committing the offences. It appears that police will only be held accountable for violence inflicted on demonstrators if the actions are captured on video.

But even then, accountability only applies to individual officers. This is far from what is meant by the term police accountability. While the police have protested loudly against the convictions, top officers have allowed individual frontline officers to be the fall guys, sacrificing them rather than taking responsibility themselves for policies in which these officers played their part.

These leaders hide behind their indignation at the convictions, confident they will never themselves face accountability for their actions.

The police force has been morally corrupted by its use as the guard dog of the regime. Its position is more precarious than at any time since the early 1970s when the force was perceived as so corrupt that nothing short of the creation of the Independent Commission Against Corruption could address it. Now, we don’t have that kind of corruption; we have moral corruption, a corruption of purpose.

It is hard to think of a single case involving the regime and its allies that the police have adequately addressed, whether the kidnappings and abductions to the mainland of Lee Bo and Xiao Jianhua by Communist agents, the attacks on Umbrella Movement demonstrators by triad-related thugs, or pro-Communist Legco member Junius Ho’s threatening pronouncement that independence advocates should be ‘killed mercilessly’.

The Hong Kong Bar Association usually sticks quite narrowly to issuing statements on legal matters, but in its submission to the Hong Kong government as part of the upcoming Universal Periodic Review of Hong Kong and China at the UN Human Rights Council, it dedicates a full four paragraphs to the police’s “increasing [deployment of] more restrict [sic]crowd control measures which had an impact on citizens’ exercising their right to freedom of assembly”.

It also notes that in spite of the fact there is a pattern of judges having acquitted defendants on protest-related charges and criticizing police for making false accusations under oath, “those police officers subject to such criticisms continue to serve on the police force with impunity”.

Remember this context when regarding the prosecutions of young people who are now being sent to prison for years for throwing bricks and bottles at police in Mong Kok.

Repercussions and implications of the Mong Kok prosecutions

Far from blindly supporting the protesters that evening, I abhor violence of any kind. I believe the struggle for democracy, self-determination and justice must remain entirely nonviolent. I understand the anger and frustration that motivated the protesters, I feel it myself, but those motives do not justify violent acts, which were not only morally unacceptable but strategically idiotic.

The protester attacks on police provided the government with its best opportunity to decimate localist groups through prosecutions, and it has proceeded to do so. At the time of Chinese New Year 2016, localism was on the rise. It represented, especially to young people, an alternative to the traditional pan-democrats increasingly seen as naïve, weak and ineffectual.

Just a few weeks after the clashes, Edward Leung placed third in a Legco by-election and appeared to be on track to securing a seat in Legco in the city-wide elections of September, though, as it turned out, he was barred from running in that contest.

Civic Passion won one seat in that election, and Youngspiration (with Baggio Leung stepping in to replace the disqualified Leung) two. Flash forward two years, and Hong Kong Indigenous and Youngspiration are all but moribund, and Civic Passion isn’t doing much better.

Localism still exists and is still influential, again especially among young people, but it has gone underground and, apart from localist-dominated university student unions, has virtually no visible institutional presence. While there are various reasons for this, the situation would surely look very different now if protesters had not attacked police with bricks and bottles at Chinese New Year 2016.

The prosecutions of protesters on ‘riot’ charges also emboldened the government to go after nonviolent pro-democracy protesters more aggressively, appealing the community service sentences of 16 protesters and procuring lengthy prison sentences as well as harsher future sentencing guidelines for convicted protesters.

Three of those prison sentences were subsequently overturned by the Court of Final Appeal, which will also hear the appeal of the 13 others in September.

The government was able to do this by dangling the spectres of ‘violence’ and ‘disorder’ in front of judges ruling on the cases of defendants who were not convicted of violent crimes or even disorderly conduct. This prosecution tactic seems to have had a hypnotizing effect, as attested to by the harsher sentencing guidelines for those convicted of nonviolent crimes committed at protests where violence occurred.

They are held responsible for violence in which they were not involved, running counter to the principle that the individual should be held accountable for his own actions, not those of others.

Hong Kong judges are not particularly streetwise. They exist in their own version of the ivory tower, swimming in their own social circles, insulated from how ordinary Hong Kong people live. They also tend to be rather conservative. This leaves them susceptible to government narratives about what is happening on the street that may bear little resemblance to reality.

The government has taken advantage of this to drive the story that Hong Kong is somehow on the verge of ‘chaos’, ‘disorder’, ‘lawlessness’ and ‘violence’, and it is incumbent upon judges to ‘do something about this’ through ‘deterrent’ sentencing and harsher sentencing guidelines. The Mong Kok police-protester violence of Chinese New Year 2016 made it much easier for prosecutors to sell this hackneyed tale to gullible judges.

Regime opponents can be forgiven for thinking that the High Court in particular does not have much sympathy with their cause. Of all the cases against pro-democracy leaders and activists and Mong Kok ‘rioters’ tried in the last two years, the High Court has decided in favour of the government in every case but one.

It has disqualified six democratically elected pro-democracy Legco members. It has upheld the barring on political grounds of National Party leader Andy Chan from running for Legco. Upon government appeal of lower court sentences of community service, it has sentenced 16 pro-democracy protesters to prison for six to 13 months for the nonviolent offense of unlawful assembly.

It has found liable of contempt of court all 20 of those tried so far in relation to the November 2014 police clearance of the Mong Kok occupation during the Umbrella Movement, and sentenced two of them to prison. A further 15 are now on trial.

So far, that’s 43 decisions in favor of the government, three in favor of the opposition. And even those three — Joshua Wong, Nathan Law, and Alex Chow — were initially sentenced to prison by the Court of Appeal and only had their sentences overturned by the Court of Final Appeal, which nevertheless upheld the Court of Appeal’s harsher sentencing guidelines for protesters issued in the case.

And that CFA decision, not least in its timing, had a suspiciously political smell to it, coming after the three had been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize . The government didn’t want their prison martyrdom to increase the chances of them winning. The message is that the High Court is inclined to side with authority and the status quo and not particularly convinced by rights-based arguments.

In summary, the most immediate repercussions of the Mong Kok violence are: dozens of imprisonments, the decimation of the localist movement, heightened Party and Hong Kong government resolve to attack political enemies, a harsher judicial climate for protesters, and continued – and arguably increased – insulation from accountability of the Hong Kong government and police force.

Not least significant, the ‘riot’ trials have highlighted the substantial and growing gap between law and justice in Hong Kong. While some of the ‘riot’ defendants may have committed crimes for which they should be held liable in a court of law, the larger issues behind the event, including police accountability and unenacted political reform that is required by law, continue to go entirely unaddressed.

As Baggio Leung, another pro-democracy activist who has faced the courts, said, “One cannot look to the courts for justice in a place without democracy.”