Jane Austen’s books are constantly adapted for television and film; her world has spun off into an entire cottage industry where people dress up as her characters and attend Regency-style balls. Now that obsession is set to reach new heights with a host of novels that draw inspiration from the author’s life and fiction.

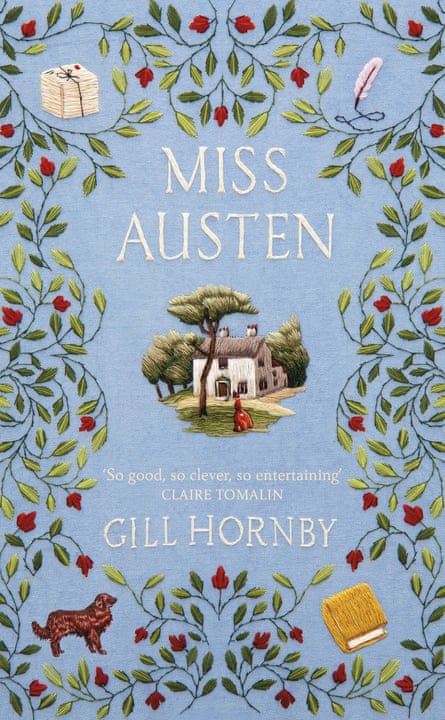

Coming in the first half of this year are: Gill Hornby’s Miss Austen, reimagining the author through the eyes of her sister Cassandra; Janice Hadlow’s The Other Bennet Sister, asking us to consider Pride and Prejudice’s Mary in a different light; and Helen Moffett’s Charlotte, picking up the story of that same novel’s Charlotte Lucas. All of them are attempts to recreate the Austen universe for different times by means of lesser-known characters, both fictional and real.

Colour portrait of Jane Austen drawn by her sister Cassandra, dated 1810. Photograph: Universal History Archive/Getty

“One of the things that inspired me was that ridiculous notion of, ‘poor Jane, she never found marriage, and those books provided her with an outlet for all her desires’. Really? Did they?” said Hornby. “The reality is that Jane was never going to marry. She had nought pence, was quite difficult, and not the kind of girl who sucked up to a man when he walked into a room. Nor I think did she care about that.”

Hornby was interested in the role Austen’s sister played in allowing the author to write. “Cassandra was Jane’s support system. She had enormous pride and investment in Jane’s work. When they’re living in Chawton, she runs the house and says: ‘You get on with it.’”

If Miss Austen delves deep into the author’s interior life – among the novel’s many highlights are a series of letters between the two sisters which Hornby admits she initially worried were something of a “liberty” – the year’s other Austen-related novels mine more familiar ground.

“Once I started thinking about Mary, I couldn’t get her out of my head,” said Hadlow, adding that she hoped The Other Bennet Sister would allow us to view the plain sibling in a fresh light. “I’ve been reading Pride and Prejudice for as long as I can remember, and Mary sits on the margins of the book and doesn’t, at first glance, have much to recommend her. She is the only plain daughter in a family of beauties … she can’t open her mouth without saying something dull or sententious. She’s still a teenager at the time of Pride and Prejudice but she’s already a prig and a bore.”

Hadlow felt touched by Mary’s plight. “I found myself feeling increasingly sorry for her and began to wonder who she might be if she was moved from the margins? What would the world of Pride and Prejudice look like when seen through her eyes? How might our sympathies shift?”

A similar empathy lay behind South African novelist Moffett’s decision to make Charlotte Lucas the heroine of her novel. Charlotte’s fate – marriage to the appalling Mr Collins – has long been seen as one of Austen’s more bleak endings, albeit a realistic one, and Moffett was keen to explore what might happen next.

“What sort of a life did she have after making a hasty and expedient marriage? What about happiness? Was that a luxury? And was love even more of a fantasy? I wanted to make clear that an ordinary life, an everyday life, even in a society that restricts women’s autonomy is worth scrutinising, recording, exploring. I wanted to look at how a woman with apparently little or no power could be an active agent in the lives of others. I think this is hugely important: the power of the apparently powerless.”

While none of this is entirely new – indeed the last decade has seen a boom in Austen-related fiction, with entire shelves given over to it in US bookshops, and authors from PD James to Joanna Trollope trying their hand at spin-offs and updates – the three novels are linked by their interest in smaller, less obviously exciting lives. It is this concentration on quiet acts of heroism that ensures that they do they far more than simply coast on Austen’s bonnet strings.

“One of the things that drew me to Gill’s novel was the way in which she presents Jane through the prism of Cassandra,” said Hornby’s editor Selina Walker. “She makes a very good case for the notion that if it wasn’t for Cassandra, then there wouldn’t be any books, and that attracted me.”

Sam Humphreys, Hadlow’s editor, agrees. “There’s always been a lot of Austen-related fiction but perhaps not always from mainstream publishers,” she said. “I suspect some of this renewed interest stems from the current climate: in times of uncertainty we tend to turn to the familiar, to our traditional sources of comfort – and who better than Jane Austen?”

Hornby herself believes the reason Austen continues to endure – a new film version of Emma is released next month – is because “we never tire of the domestic novel. Her themes are ageless – difficult mothers, malicious sisters-in-law, dodgy boyfriends, the immediate horizons of the town or village you live in. These are the eternals of a civilised society.”

And, says Hadlow, they are also fun to read. “Not all of the works inspired by great books are seen to be great art but I don’t think it matters,” she said. “It’s a testimony to the power of the original novels, a declaration that they continue to matter, that they can still touch the lives of readers so profoundly that they feel moved to create something of their own as a result.”