Back in February, Microsoft made the surprising announcement that the Windows development team was going to move to using the open source Git version control system for Windows development. A little over three months after that first revelation, and about 90 percent of the Windows engineering team has made the switch.

The switch to Git has been driven by a couple of things. In 2013, the company embarked on its OneCore project, unifying its different strands of Windows development and making the operating system a more cleanly modularized, layered platform. At the time, Microsoft was using SourceDepot, a customized version of the commercial Perforce version control system, for all its major projects.

SourceDepot couldn't handle a project the size of Windows, so rather than having the whole operating system in a single repository, the Windows code was actually divided among 65 different repositories, with a kind of virtualization layer on top to produce a unified view of all the code. Some of these 65 repos contained nicely isolated, standalone components; others took vertical or horizontal slices through the operating system; others were just grab bags of different code. As such, the repo structure didn't correspond with OneCore's module boundaries.

Microsoft wanted a structure that better fit OneCore. It also wanted a system that better fit the development of "Windows as a Service" and the move from making one major release every three years to making a smaller release every six months. Windows development has been substantially opened up compared to the Windows 7 and Windows 8 days, with much more customer feedback through the Insider Program. The development team is trying to be much more responsive to bug reports and suggestions coming from Windows users, and this changed the demands placed on the version control system.

Even with its customization and multiple repositories, the scale of the Windows codebase, some 3.5 million files in total, pushed SourceDepot to the limit. Creating a branch took the better part of a day, with a performance-imposed limit of about 500 branches total. Groups had to think long and hard about whether they would actually create a branch—they certainly weren't going to create one on a whim—and would then have to scavenge someone else's branch if they decided that they really needed one; they would have to find an old, unused branch and ask the team that created it to kill it off so that the system would have capacity for the new branch.

Addressing these performance concerns was the second big driver for the switch away from SourceDepot to something new.

More broadly, the company wanted to develop a single engineering system ("1ES"), spanning not just version control, but bug tracking, building, and more, that could span the entire company. Presently, different teams use different systems; some had already migrated to Git on their own, but other, larger, older products are on SourceDepot. The other aspects of application lifecycle management (ALM) are being handled Visual Studio Team Services (VSTS), the cloud-hosted version of the Team Foundation Server ALM system.

The switch to Git

Due to widespread developer familiarity and strong support for creating lots of branches with low overhead, the decision was made to use Git as the new system. But Git isn't designed to handle 300GB repositories made up of 3.5 million files. Microsoft had to embark on a project to customize Git to enable it to handle the company's scale.

This work has proceeded along three main paths. The first is the Git Virtual File System (GVFS) project, which allows the repository to be cloned (that is, copied from the remote server to a local, modifiable copy that developers actually work on locally) without having to replicate all 300GB at once. Instead, a skeleton copy of the repository is created locally, and as files are opened they're pulled on an as-needed basis from the Git server. The server components similarly needed to be updated to handle this style of operation.

The second is to make algorithmic improvements to Git itself. Microsoft found that Git would often touch files unnecessarily; this meant that GVFS would fetch those files similarly unnecessarily and that operations on the repository got slower as the number of files in the repository grew. With 3.5 million files, even simple operations such as git status, which shows which files have been modified and have changes that need to be committed, took about 30 minutes. The company made algorithmic improvements to improve the scaling and made many operations "aware" of GVFS, only touching those files that were actually available locally—files that GVFS hasn't yet requested from the server obviously cannot be changed, so they do not need to be checked for changes. This first pass took the git status down to about 9 seconds.

This helped considerably, and with these changes in place Microsoft moved about 2,000 Windows devs to using Git back in March. However, the company then noticed that performance got worse the longer a developer worked on their local repository; the average git status had crept up to 11 seconds. The reason for this was that as the developers went about their jobs, they'd touch more and more files. Often these files weren't actually modified, just fetched incidentally while building or debugging something else, but the net result was that the local repository became bigger and bigger over time.

This has led to a second round of optimization work: changing Git so that, to as great an extent as possible, its performance scales not with the total number of files in the repository (as it was initially), nor even with the number of files retrieved and stored locally (as it was with GVFS), but with the number of locally stored files that have been modified. git status is now down to 2.3 seconds, and the company's goal is to get it under one second.

The third thing the company has done is build a Git proxy server so that remote teams with higher latency, lower-bandwidth connections can work on the Windows code without too much pain. Cloning the Windows repository from Redmond takes about 127 seconds; the repository itself is hosted in Azure on the West Coast, so bandwidth is high and latency is relatively low. The same operation from the company's North Carolina office was taking 25 minutes. With the introduction of the proxy, this has dropped to 70 seconds—it's actually quicker than in Redmond, because the latency to the proxy is even lower than the latency between Redmond and Azure.

Big numbers

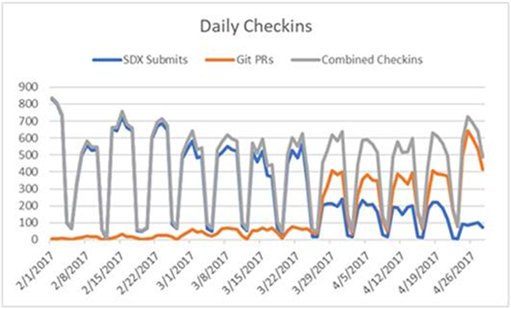

The result? The Windows repository now has about 4,400 active branches, with 8,500 code pushes made per day and 6,600 code reviews each day. An astonishing 1,760 different Windows builds are made every single day—more than even the most excitable Windows Insider can handle.

Where Source Depot tended to force branches to be kept long term (because it was so painful to create a new one), the company can now use a more conventional model of short-lived branches, where a branch is created for a specific feature, development is done on the branch, merged into the main tree, and the branch closed. Git aficionados might be surprised that many of the details of how Git is used are left for teams to decide themselves. The Git community has its own version of the tabs versus spaces debate: whether merges should use rebasing, squashed commits, or full commit history. This is a religious issue—some people greatly prefer to see the individual commits and accurate history of individual commits, others prefer the cleaner history that comes of rebasing and squashing—and different teams have different policies. Squash commits are more popular overall.

Git is, of course, open source. Microsoft has forked the Git client to make it understand GVFS and use algorithms that scale according to the number of modified files. Presently, GVFS has to be used with the Git server that's part of VSTS, as only that has the required extensions to serve files the way GVFS requires. The company's ambition, however, is to do away with these forks and have as much of the work integrated into the mainline as possible—with the ultimate goal being to get all of its modifications accepted by the main Git developers and incorporated into the standard Git codebase.

To ease that, the company is moving from Android-style development—where development occurs in private, with occasional public code drops—to developing "in the open," with regular updates and openness to outside contributions. Third parties have already shown interest in the work: Atlassian SourceTree has added GVFS support, and Tower Git will soon add support. Visual Studio's integrated Git support will add GVFS support in Visual Studio 2017 Update 3.

Microsoft also says that it has had discussions with both Google and Facebook—both of whom face similar scale issues—about its Git development. These companies both have their own internal systems to handle their workloads, and it's possible that we may start to see collaboration between the companies in the future.

The last parts of the Windows team that are using SourceDepot should make the switch to Git over the next few months. After that, the new system will be rolled out beyond the Windows division, with other development teams making the switch.

reader comments

160