On July 19, 1989, one of the most dramatic events in aviation unfolded in the skies over Iowa as heroic pilots battled to land a crippled DC-10.

There was a festive atmosphere in first class that day, July 19, 1989, on United Flight 232. Virginia Jane Murray, a thin, youthful, 34-year-old flight attendant with bleached silver hair, stopped to talk with passengers Bill and Rose Marie Prato and Harlon "Gerry" Dobson and his wife, Joann, from Pittsgrove Township, N.J. The ladies were dressed in muumuus, and their husbands wore Hawaiian shirts. They were laughing and enjoying the perfect ending to their trip. "It was obvious they'd had a wonderful vacation," Murray said more than two decades later. "They were just very pleasant people. I think about them all the time."

On the flight deck of the McDonnell Douglas DC-10, the crew ate lunch in their seats, as usual. William Records, the first officer, was flying the Denver-to-Chicago leg of the trip with Capt. Alfred Haynes in the left seat acting as his copilot. Behind Records, Dudley Dvorak, the second officer, was monitoring all systems. DC-10s were introduced in the early 1970s as McDonnell Douglas's entry in the new class of wide-body aircraft, which included the Lockheed L-1011 and the Boeing 747. The most distinctive feature of the three-engine DC-10 and the L-1011 was a turbofan mounted through the tail. The DC-10 carried a maximum of 380 passengers; on this flight, there were 296 people, including crew, on board.

It was 3:16 pm, a bit more than an hour into the flight. The lunch trays had been cleared away; Haynes was nursing a cup of coffee. With the plane on autopilot, the crew had few tasks to perform until the time came to descend into Chicago. "Everything was fine," Haynes said many years later. "And there was this loud bang like an explosion. It was so loud, I thought it was a bomb."

Records lurched forward and took the control wheel, or yoke, saying, "I have the airplane." The DC-10 slewed hard to the right. It shuddered and shook violently, almost immediately climbing 300 feet, as the tail dropped sharply. Dvorak radioed the Minneapolis Air Route Traffic Control Center in Farmington, Minn., "We just lost No. 2 engine, like to lower our altitude, please."

While Records struggled with the controls, Haynes called to Dvorak to read out the checklist for shutting down the failed engine, the one mounted through the tail. The first item on the list said to close the throttle, but the throttle would not go back. "That was the first indication that we had something more than a simple engine failure," Haynes said later. The second item on the list said to turn off the fuel supply to that engine. "The fuel lever would not move. It was binding." Haynes felt a deep wave of concern surge through him. Events were unfolding at lightning speed. Only a minute or so after the explosion, Records said, "Al, I can't control the airplane."

The DC-10 had stopped its climb and begun descending, rolling to the right. Haynes said, "I've got it," and took hold of his own control wheel. "As the aircraft reached about 38 degrees of bank on its way toward rolling over on its back," Haynes explained later, "we slammed the No. 1 [left engine] throttle closed and firewalled the No. 3 [right engine] throttle." By putting all the power on the right side of the plane, Haynes forced the DC-10 to yaw to the left. This meant air was flowing slightly faster over the right wing, generating more lift.

After a few agonizing seconds, the right wing slowly came back up. If Haynes had not decided—somehow, reflexively—to steer the plane with the throttles, the crippled DC-10 would have rolled all the way over and spiraled to the ground, killing all on board. Haynes had no idea what made him use the throttles. Nothing in his training would have suggested it. Now as Dvorak watched his instruments, he was horrified to see the pressure and quantity in all three hydraulic systems fall to zero.

When the head flight attendant, Jan Brown, heard the explosion, she went to the floor and held on to the nearest armrest until the plane was stable. After a minute Dvorak's steady voice came over the loudspeaker and explained that they had lost the No. 2 engine. But the plane had two other engines, one on each wing. The plane would descend to a lower altitude and fly more slowly to Chicago.

Then the chime rang at Brown's station. She could see most of her crew and knew that the call was not coming from any of them. Long experience told her that if the cockpit was calling at this point in the flight, it could be nothing but bad news. She picked up the handset and her fear was confirmed by Dvorak's voice. He told her to report to the flight deck. She hung up and walked up the port-side aisle, trying to look calm. "I knocked on the door like we're trained to do," Brown said. "And the whole world changed just in that instant when that door opened." She saw no panic, she said. "It was what was in the air. It was so palpable. I remember thinking, this isn't an emergency, this is a crisis."

Brown watched Haynes and Records wrenching the control wheel back and to the left as the plane tipped more and more steeply to the right. "I could just feel the strength that was being put into that motion from both of them."

Haynes said, "We've lost all hydraulics."

Although Brown was not the sort to panic, she explained, "I have not found the appropriate word that can describe the pure terror of an airplane that was always my friend, that I knew in the dark. But now it's a metal tube, and it holds my fate. And there's nowhere to go. There's nowhere to hide."

As she passed through first class, she decided she could not call the crew together for a briefing. It would be too obvious to the passengers. She would talk to them quickly and quietly, wherever they happened to be. In the forward galley she caught Murray and Barbara Gillespie, the two first-class flight attendants, and began telling them what Haynes had said. Then Brown squared her shoulders, forced herself into an attitude of professionalism, and began walking down the aisle, trying to figure out how to protect the babies that some passengers were holding in their laps.

Murray, her heart sinking, continued cleaning up after lunch. What Brown had told her merely strengthened her conviction that she was going to die. Earlier, while serving the meal, Murray had chatted with Dennis Fitch, a DC-10 instructor at the United training facility in Denver who was on his way home for the weekend.

Fitch was the oldest of eight siblings, and, as such, he had developed what he called people radar. He could spot a distressed person at 100 yards, he liked to say. Now, as Murray rushed past looking grave and worried, Fitch reached out and stopped her. She leaned down. "Don't worry about this," he told her. "This thing flies fine on two engines."

Murray spoke softly so as not to be overheard. "The captain told us that we have lost all our hydraulics."

"That's impossible," Fitch told Murray. "It can't happen."

"Well, that's what we're being told," Murray said.

Fitch thought about that for a moment. "Would you go back to the cockpit? Tell the captain there's a DC-10 training check airman [TCA] back here. If there's anything that I can do to assist, I'd be happy to do so."

Fitch watched Murray go forward as quickly as she could without alarming the passengers. Fitch had been on full alert for a while now, and this development was baffling and chilling. As a TCA, Fitch trained pilots for every conceivable emergency, week in and week out, yet nothing he was seeing or hearing made sense. A DC-10 can't lose all hydraulics and continue to fly in a controllable fashion. On small aircraft the moveable surfaces used to steer the plane—the rudder on the vertical stabilizer, the elevators on the horizontal stabilizer, and the ailerons on the wings—are controlled by cables and rods with a physical connection to the pilot's yoke and pedals. On airliners the control surfaces are so large and the airstream so powerful that hydraulics are needed to move those surfaces. When the pilot moves the yoke, he is moving a cable that moves a switch that turns on the hydraulic power to move the rudder or elevators or ailerons. Without fluid in the hydraulic lines, Flight 232's crew had no way to steer the plane, or extend flaps, slats, and spoilers on the wings to slow the airplane for landing. And even if they managed to get the craft on the ground, they had no brakes. Although most of the passengers didn't yet know it, Flight 232 was doomed to crash.

At Sioux City Gateway Airport, about 65 miles to the southwest, the phone rang in the tower cab—a glass fishbowl atop the terminal building with a 360-degree view of the field and the surrounding Iowa farmland. It was a controller from Minneapolis Center. "Sioux City, got a 'mergency for ya," a voice said.

Kevin Bachman, the Sioux City approach controller, replied in his native Virginia drawl: "Aw-right." He listened to the breathless, speedy voice of the controller trying to bark out information that had clearly scared him out of his wits. "I gotta, let's see, United aircraft coming in, lost No. 2 engine, having a hard time controlling the aircraft; right now he's outta twenty-nine thousand, right now on descent into Sioux City, right now he's—he's east of your VOR [Very High Frequency Omnidirectional Radio Range], but he wants the equipment standing by right now."

Bachman could see United Flight 232 on his radar screen, a bright electronic blip showing the plane's altitude and an identifying transponder code beneath. "Radar contact," he said.

Then Haynes said, "Sioux City Approach, United two thirty-two heavy." (The term heavy is added to the call sign of DC-10s, 747s, and other aircraft large enough to cause dangerous turbulence in their wake.) "We're out of twenty-six, heading right now is two-nine-oh, and we got about a 500-foot rate of descent." He meant that the plane was passing through 26,000 feet, traveling roughly west, and losing 500 feet of altitude every minute.

Bachman told him that he could expect to land on Runway 31.

Haynes responded, "So you know, we have almost no controllability. Very little elevator and almost no ailerons; we're controlling the turns by power. We can only turn right, we can't turn left."

Bachman could see that on its present track, the plane would wind up 8 miles north of the airport. He decided to adjust the heading and told Haynes, "United two thirty-two heavy, fly heading two-four-zero, say souls on board and fuel remaining."

"We have thirty-seven-six fuel," Haynes said, "and we're countin' the souls, sir." He meant that the plane had 37,600 pounds of fuel. (Fuel on planes is measured in pounds, not gallons or liters.)

Dvorak heard a knock on the door and opened it to find Murray standing there. The flight attendant's eyes grew wide as she saw the state of affairs on the flight deck. "I hollered in there," she explained later. "I said, 'You have a training check airman back here if you need him.' "

"Okay," Haynes said. "Let him come up."

Murray backed away fast, shaking from shock.

Addressing Bachman by radio, Haynes began, clipped, staccato, breathless: "I have serious doubts about making the airport. Have you got someplace near there that we might be able to ditch?"

The airplane, Bachman realized, was going to crash. He had no idea how to respond. "United two thirty-two heavy, roger, uh, stand by."

When Fitch reached the cockpit, he said later, Haynes and Records "were in short-sleeved shirts, the tendons raised in their forearms; their knuckles were white." As he closed the door behind him, his eyes flicked over the instruments and switches on Dvorak's panel. The navigation was working normally, and the plane had electrical power. But the hydraulic gauges read zero and the low-pressure lights were on. Fitch saw that Records didn't even have his shoulder harness fastened. He leaned over him and fastened it.

Haynes later said that Fitch "took one look at the instrument panel and that was it, that was the end of his knowledge."

The plane was porpoising in a slow up-and-down cycle of hundreds of feet every minute, even as both Haynes and Records fought the yoke to no effect. On the radio, Dvorak was pleading for help from United Airlines Systems Aircraft Maintenance in San Francisco, but the United engineers kept repeating that what Dvorak was describing was impossible.

"Okay," Fitch said to Haynes, "tell me what you want, and I'll help you."

"What we need," Haynes said, "is elevator control, and I don't know how to get it."

Fitch was confused but willing. He stood between the two pilots, took the throttles in his hands, and began to move them in accordance with instructions from Haynes and Records.

"Start it down," Haynes coached. "No, no, no, no, no, not yet … wait a minute till it levels off … now go!"

Immediately after the explosion, the plane had made one big slow right turn about 20 miles in diameter. Then it proceeded to make several more spirals of 5 to 10 miles each, downward and to the right. The DC-10 was flying the way a paper airplane would fly if thrown from a height—first nose down, then nose up, nose down, nose up. The plane descended, rapidly gaining speed. The increased speed produced more lift on the wings, causing the plane to climb. As the speed bled off in the climb, the wings lost lift, and the plane resumed its descent. And so it went, each oscillation taking a minute or so. The plane always wound up at a lower altitude. They were going to return to earth no matter what. That motion is called a phugoid oscillation, and the crew well understood that they could not possibly land safely without putting an end to it. So they tried to control how much the right wing dropped and how much the ship pitched up and down during each cycle. They tried to anticipate the behavior of the craft, and, in fact, they were gradually "getting in tune with the airplane," as Fitch later put it. But, as a TCA, he knew that in the 25 years before this event no one had ever survived the complete loss of flight controls in an airliner. They were merely buying time.

Haynes began an announcement to the passengers. He explained that they would attempt an emergency landing at Sioux City and that his signal, before they met with the earth, would be the word "brace," said three times. A roar of anxiety and despair arose from the coach cabin. Many passengers recalled that Haynes also said, "This is gonna be the roughest landing you've ever had."

When Jan Brown completed her safety briefing for the passengers, she tried to think whether she had covered everything "and then I see parents, lap children." She made another announcement, telling passengers to put their children on the floor. "As I'm saying this, I'm like, oh, my God, this has got to be the most ludicrous, ludicrous thing I've ever said in my life. I'm telling people to put their prize, treasured possession on the floor? In other words, let's just hope for the best. Everybody else has a seatbelt. I was so appalled at what I was saying."

Then her cabin fell silent, save for the restless, uneven throbbing of the engines.

At 3:46 pm Fitch began the only left turn that the disabled plane was ever to make. He'd had 20 minutes of practice at steering with the throttles, and this was his finest performance. The crucial maneuver put the plane on a southwesterly course direct to Sioux City at nearly the correct altitude to make the runway. The runway, however, had a big yellow X painted across the approach end to let pilots know that the World War II–era relic was permanently closed.

After giving the passengers a 10-minute warning, Haynes discussed with the crew how to put the wheels down without hydraulics. They decided to follow abnormal procedure and lower the landing gear manually by using handles under the cockpit floor. Once that was done, Haynes said, "Okay, lock up and put everything away."

Fitch had been standing the whole time, but he would not have any hope of surviving if he stood during the landing. Dvorak offered Fitch his seat to run the throttles for the final minutes of the flight. Dvorak strapped himself into the jump seat behind Haynes and announced to the passengers, "We have 4 minutes to touchdown, 4 minutes to touchdown."

The compass read 220 degrees, or southwest. Haynes, for one, had been convinced that they would never make it to any runway. Yet here they were, pointing right at Sioux City airport and a usable stretch of cracked and weedy 1940s concrete. He peered out into the bright sunlight and asked, "Is that the runway right there?" Elated, he told Bachman in the control tower, "We have the runway in sight! We'll be with you very shortly. Thanks a lot for your help." You could hear the relief in Haynes' voice. They had rolled the wings level, and, all at once, Haynes saw the sight that for decades had represented safety and relief for him and the accomplishment of the ultimate goal of any aviator: to return safely. To bring your people home.

The control tower fell eerily silent. The controllers had brought the flight in, and now they could almost hear the applause. A hundred and twelve seconds remained in the flight when Bachman said, "United two thirty-two heavy, the wind's currently three-six-zero at one-one. Three-sixty at eleven. You're cleared to land on any runway."

Haynes laughed. "You want to be particular and make it a runway, huh?"

In the control tower, some of the men chuckled. The tension went out of the room. Everyone believed that Flight 232 had it made. Maybe it would roll off the end of the runway into the corn. Of course, the crew would deploy the evacuation slides. The fire engines would respond. But in that moment of levity, they were all convinced that the crippled DC-10 was going to land safely.

A few seconds later the aircraft appeared over the bluffs in the intense blue sky, now populated by an afternoon buildup of cumulus clouds that had appeared like great white schooners, as the sun baked the rain off the land. Hundreds of people were watching—all the other controllers who had joined Bachman in the tower, as well as scores of firefighters, police, and National Guard. The great winged shape of the jumbo jet wasn't floating the way airliners ordinarily seem to, that deceptive illusion of slow motion. Rather, this plane was howling down the glide slope, dropping like a stone.

When the plane lined up with Runway 22, Fitch understood that they had 360,000 pounds of flesh and metal going nearly 250 mph with no way to stop it. "But," Fitch later said, "the beautiful thing was that at the end of the runway was a wide-open field laced in corn." Flight 232 would be landing, in effect, on a rich, green, midsummer farm.

At an altitude of about 400 feet, Haynes saw their excessive speed and was concerned that the tires would explode on contact. Normally, the plane would land at about half its present speed. Haynes told Fitch to take the power off. Fitch later said that he had planned to close the throttles as the plane touched down, "but then I looked over to see the incredibly high sink rate, 1800 feet per minute, three times in excess of the structural capability of the landing gear. So I firewalled both the engines." He stretched his arms forward as far as he could reach, straining against his harness.

The left engine spooled up to almost 96 percent power, while the right reached only 66 percent at first. It's possible that Fitch pushed both throttles the same amount and the engines happened to respond that way. The relationship between the position of the throttle and the thrust that an engine produces is not linear. Whatever the case, the right wing went from about 2 degrees of bank to more than 20. This happened less than 100 feet above the ground, and it happened fast. Once the right wing began to drop, it took a fraction of a second for it to tear into the runway at roughly the same time that the right landing gear began gouging an 18-inch-deep trench through the World War II concrete.

When the plane pancaked onto the runway, more than 10,000 pounds of kerosene came out all at once from the ruptured right wing and turned to mist. The No. 2 engine came out of its mount and the tail snapped off and went tumbling away. The single remaining engine, mounted on the left wing, was still running full throttle. "Like a pinwheel, it [the left wing] is causing the airplane to rotate, because the engine's pushing it around," Fitch said. "When the tail broke off, the airplane is much heavier forward, so the airplane is now coming up in the air like a seesaw that somebody got off. And the cockpit is getting pointed straight to the earth, and we skip like a pogo stick. The first skip, when I saw the windshield go dark brown and green, we were still integral to the aircraft." But on the second skip, "the stress caused the cockpit to break off like a pencil tip."

As that was happening, the lift on the left wing, as well as some thrust, perhaps, from the left engine, powered the plane around in a complete 360-degree rotation on its nose, spinning like a top. A fireball and smoke rose from the middle portion of the plane as banks of seats began vaulting and somersaulting high above the flames. Some of the banks of seats were thrown far above the fuselage in great parabolas, shot as if from a cannon by the centrifugal force of the aft end of the fuselage swinging in its majestic, flaming arc. What must it have been like to take that ride, alive, aloft, alone, aware, unhurt as yet, and looking down on the green earth? Finally, the plane angled over and landed on its back.

Moments later a storm of paper began rising on the heat waves above the main body of the fire. It turned in a slowly rotating vortex, like a mythical creature, and began drifting down around the ambulances and fire trucks and pickup trucks and cars that rumbled out onto the runway. In the tower the controllers stared in silence at a scene they could scarcely comprehend, as a sunny Iowa summer day turned into a gray and wintry landscape.

Bachman turned away from his position and fell to his knees, hanging his head. Mark Zielezinski, the control tower supervisor, put his hand on Bachman's shoulder, said Bachman, and he "told me that I had done everything I could." Bachman stood up, quaking and ill, and went unsteadily down the stairs and burst into tears.

Jim Walker, a pilot with the 185th Tactical Fighter Group of the Iowa Air National Guard, which had its headquarters at the airport, assumed that no one could have survived the crash. But then another pilot, Norm Frank, screeched to a halt in a pickup truck and said, "Get in, we're going to pick up survivors." Walker boarded the truck, and Frank raced onto the field.

There were bodies everywhere. "We just sat there looking at all these dead people," Walker said. Most of them were lying in the grassy easement between the concrete and the crops. "And the most surreal thing I've ever seen in my life happened next. It actually looked like something from Night of the Living Dead, because many of these bodies all of a sudden started sitting up." Walker watched in amazement as a businessman in a suit stood and looked around as if searching for something. "He walked over and grabbed his luggage" and walked away, the National Guard pilot said.

In the glass-walled control tower Charles Owings, one of the controllers, broke the silence and radioed all aircraft on the frequency that Sioux City Gateway Airport was now officially closed.

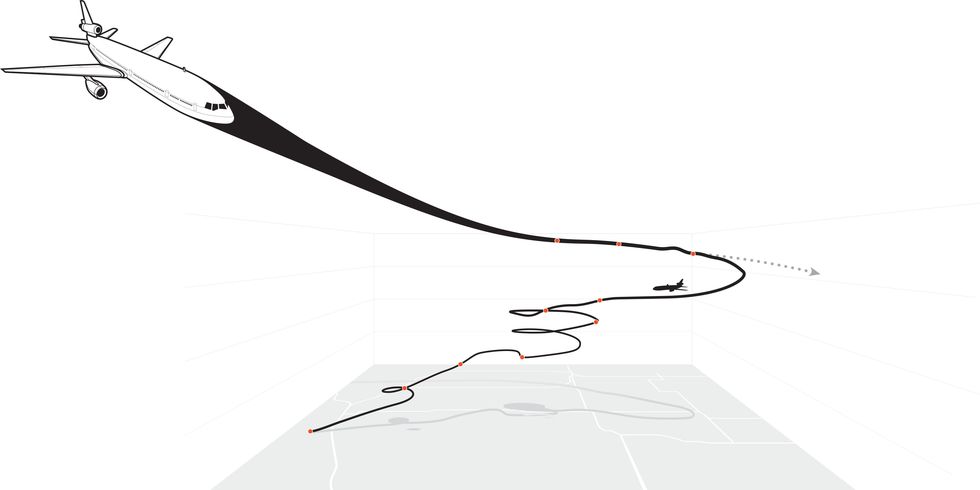

The Way Down

On July 19, 1989, United Flight 232 was about an hour out of Denver en route to Chicago when the engine in the tail of the DC-10 blew, destroying the three hydraulic systems pilots use to move flight control surfaces and steer the plane. As the airliner descended in looping circles, the crew tried heroically to make an emergency landing at the Sioux City, Iowa, airport by using only the thrust of the remaining two engines to control the aircraft.

3:14 pm At an altitude of 37,000 feet, the plane begins a right turn over Iowa, on a heading for Chicago.

3:16 Engine No. 2 explodes; titanium shrapnel severs hydraulic lines in the horizontal stabilizer.

3:18 The hydraulic fluid drains, eliminating the crew's ability to move the plane's control surfaces. As the DC-10 rolls sharply to the right, Capt. Haynes discovers that by throttling up on the right engine and down on the left, he can—barely—steer the crippled plane.

3:26 At 26,000 feet the plane completes a 20-mile loop—the first in a series of downward, right-hand spirals. (Turns are in that direction due to the extensive damage on the right side of the nacelle, or engine housing, in the tail, which creates drag like a paddle in water.)

3:29 At 21,700 feet Flight 232 starts a second turn.

3:31 Capt. Dennis Fitch, a DC-10 instructor who happens to be on board the flight, takes control of the throttles in an attempt to steer the plane.

3:45 At 9220 feet the plane starts to make its only left turn of the event.

3:49 At 7091 feet the crew manually opens the wheel-well doors and lets the landing gear fall into position.

3:52 At just 3500 feet the plane makes a final, crucial 360-degree turn that puts the plane at the correct altitude to land at the Sioux City airport. Flight 232 is descending at a sink rate of 1800 feet per minute, more than three times faster than the landing gear can withstand.

4:00 As the plane nears Runway 22, it is traveling at nearly 250 mph—about twice as fast as normal. Less than 100 feet off the ground, Fitch advances both throttles. The left engine powers up to nearly 96 percent, while the right one lags behind at 66 percent. The right wing drops 20 degrees, hitting the runway and initiating the breakup of the plane. Fire and smoke envelop the central fuselage.

(Diagram by Martin Laksman)

Of the 296 souls on board Flight 232, 185 survived. Seven of eight flight attendants, including Jan Brown and Virginia Jane Murray, survived, as well as the three crew members and Fitch in the crushed cockpit. Returning vacationers Joann Dobson and Bill and Rose Marie Prato were killed; Gerry Dobson died a month later.

The National Transportation Safety Board report concluded that the titanium first-stage fan disc on the No. 2 engine exploded because of a manufacturing defect that had created a hairline crack. The disc split in flight, destroying all three of the plane's hydraulic systems. Within months of the crash, the Federal Aviation Administration had formed the Titanium Rotating Components Review Team to improve the manufacturing and inspection of all spinning parts on turbines.

For at least a decade prior to Flight 232 the DC-10 had been falling out of favor with airlines; after Sioux City, some pilots refused to fly it. The plane's last scheduled U.S. passenger flight was on Jan. 7, 2007.

This July, on the 25th anniversary of the crash, a series of community events in Sioux City will honor first responders and survivors and commemorate those who died.

Excerpted from Flight 232: A Story of Disaster and Survival, by Laurence Gonzales. Visit laurencegonzales.com. This story originally appeared in the May 2014 issue of Popular Mechanics.