Why Protecting Recipes Under Intellectual Property Law May Leave a Bad Taste in Your Mouth

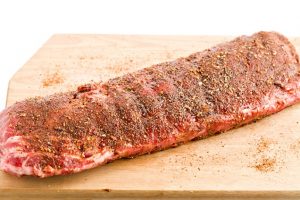

Dry rub is more complicated than it looks, from an IP perspective at least.

Living and practicing out of Texas, one comes to appreciate good ol’ Texas barbecue. Pitmasters take immense pride in their product, working combinations of everything from the type of meat and spice rubs to the types of wood smoke and duration of cooking to provide the “perfect” barbecued meat. They are also quite guarded about the composition of their “secret” rubs, sauces, wood smoke – you name it. Without necessarily knowing it, they are taking an decent course of action to protect their intellectual property rights in and to their “recipes”, but there is actually more to such protection than meets the taste buds.

Early Adopters Of Legal AI Gaining Competitive Edge In Marketplace

Restaurants and chefs are always looking for the next great culinary creation, but may also be invested in signature dishes or items (like those derived from family recipes handed down for generations). Each of these dishes and items help distinguish restaurant establishments from one another, and in the competitive world of the restaurant business, every little bit counts. In fact, these considerations are not limited to restaurants – bakeries, breweries and wineries benefit as well, to name just a few. What may be pleasing to the palate, however, is not always acceptable under intellectual property law.

Before digging in, it is important to think about recipes in a broader perspective so as to understand what is being protected, and barbecue provides a tempting example (my apologies, vegetarians). One of the most popular forms of barbecue is smoked brisket, a specific cut of beef that requires a long, slow cooking time so as to allow the meat to properly tenderize. That said, proper preparation can include not only the quality of the cut of beef, but how it is trimmed and prepared prior to smoking. Often, a spice rub composed of unique compositions of spices is prepared and used, being rubbed on the meat a then letting the meat “rest” with the rub prior to actual smoking. As noted above, different types of wood can be used to smoke the meat, the may be a “good smoke” or “hot” smoke for a specific period go time depending upon the recipe, and these steps merely scratch the surface. As you can see, smoked brisket that you eat is more than just the simple “recipe” of components – it is a combination of various elements, techniques, processes and steps that make-up the end-product. This is the case with many other “recipes” as well, from baked goods to the brewing of beer.

Sponsored

Navigating Financial Success by Avoiding Common Pitfalls and Maximizing Firm Performance

The Business Case For AI At Your Law Firm

Legal AI: 3 Steps Law Firms Should Take Now

Navigating Financial Success by Avoiding Common Pitfalls and Maximizing Firm Performance

With this perspective, one would think that all of these elements and techniques would be protectable, but think again. When it comes to patents, copyrights, trademarks and trade secrets, such “recipes” do not always conform to the requirements for such protection. To explore how one can protect a “recipe”, it is best to explore how each of the pillars of intellectual property may (or may not) apply.

Patent law, for example, is usually the least likely area of protection for a recipe, at least in the traditional sense. Why? Although patents may be granted for any “new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof” under 35 U.S.C. Section 101, the “recipe” would need to be both “novel” under 35 U.S.C. Section 102 and not obvious “to a person having ordinary skill in the art to which the claimed invention pertains” under 35 U,S.C. Section 103. In most cases, the “recipe” simply cannot meet the novelty requirement, and even if it does, would the inventor really want the recipe to be publicly disclosed in an issued patent? Probably not. Moreover, trademarks may help distinguish the dish from others from a brand perspective, but when it comes to protecting the elements if the “recipe”, trademarks provide no viable protection. Even so, at least trademark law would apply to the actual branding of the end product.

Copyright law is also of little help here, and you don’t have to take my word for it – the U.S. Copyright Office says so:

Sponsored

Is The Future Of Law Distributed? Lessons From The Tech Adoption Curve

Early Adopters Of Legal AI Gaining Competitive Edge In Marketplace

Essentially, the mere listing of ingredients does not present a modicum of originality that is essential for copyright protection. To the extent there is more actual literary expression (such as illustrating the steps for combining the ingredients and cooking times to achieve the end product in a cookbook), only then will copyright attach. That said, creating such literary expression so that it can be held and used in confidence by a restaurant establishment or chain as an unpublished work may provide some level of protection under copyright law, but doing so will require additional documentation to effectively protect the ‘recipe” — such as implementing the appropriate confidentiality agreements regarding the “recipe” — and effective employee policies and enforcement mechanisms to police such confidentiality.

Given the foregoing, we are now left with trade secrets. Whether most know it or not, keeping the “recipe” secret” is probably the most protective mechanism that can be employed for a “recipe”. Trade secrets, however, require more than simply keeping the recipe secret (sorry, Grandma). Trade secrets are protected by statute in every state except for New York and Massachusetts, which rely on common law as opposed to a codification of some form of the Uniform Trade Secrets Act. Further, protection may be available under the federal Defend Trade Secrets Act under 18 U.S.C. Section 1836(b). That said, trade secret protection requires that the owner of the trade secret take specific steps beyond ensuring that the “recipe” is actually kept secret, including but not limited to whether the information is known outside the business, is of commercial value by virtue of its being secret, and whether the information could be easily derived or duplicated by others.

The point here is not to provide an exhaustive list of factors for the application of trade secret law to a recipe”, but to stress that trade secret law (and to an extent, copyright law regarding the literary expression of the recipes in a handbook used in the business), provide a framework to address many aspects of a “recipe”, along with sound employment policies and procedures that should include strong non-disclosure agreements and enforcement. Of course, there are many variables at play that may affect such protection and enforcement, but this framework at least provides an argument in favor of protection. These practical points are better than nothing, and address many elements and processes that comprise a “recipe”, and how intellectual property protection must be woven with sound business practices to best protect them. If you don’t heed them, the entire experience of protecting your “recipes” will most likely leave a bad taste in your mouth.