The man standing in front of the Reference Desk asked for a guest pass for the public computers and then leaned forward conspiratorially. "Have you seen the original 'Star Trek'?"

I printed the pass and shook my head. "I haven’t. Are you looking for the DVDs?"

"No," he said. "You look exactly like this really sexy actress from the show. I mean, she was on the 'Hottest Women of Star Trek' list. And you look just. Like. Her."

He was leering now, staring at me hungrily, with unearned intimacy. He had a disheveled, vaguely Steve Bannon-esque look to him and appeared to be in his late 50s or early 60s.

Dealing with uncomfortable patron questions was an everyday occurrence for me, as it is for most public librarians. I found the best strategy to be a brief nod (acknowledge you heard the comment so he doesn’t repeat himself) and a curt, "OK, is there something in the library I can help you find?"

There wasn’t. He walked over to the public computers, and I would have forgotten about the interaction if he hadn’t reappeared a few minutes later.

"Can you help me print something?"

I nodded and walked with him back over to his computer terminal. On the screen was a picture of a blonde actress and the accompanying description, written by the "Hottest Women List" writer. It read, in part, "The main thing she has going for her is the sex fantasy of ‘I am new to human sensations. Please teach me how to kiss, hug, [insert depraved sex act here].’ Um, Yes Please!"

The patron looked from the screen to me excitedly.

"See! You look just like her!"

I shrugged.

"Well, I want to print her picture." He insisted. "Do you have a color printer?"

We did. I showed him how to enlarge and print the image. He left the library shortly after, waving the picture at me and winking before exiting through the library’s double doors.

When the #TimesUp movement was announced, I was pleased to see the focus on service industries where much of the job is being friendly and available to customers and clients. Because the truth is, every female and non-binary public librarian has dozens of stories just like this one; uncomfortable, but harmless interactions of harassment. We roll our eyes in the staff room, gripe to our friends and significant others after particularly egregious offenses, but tend to consider these offenses as an unfortunate, but inevitable part of the job. One of my former coworkers described library harassment perfectly as, "I just remember the trapped feeling of being a captive audience." After all, sexual harassment is about power and vulnerability, and a captive audience — like a librarian who can’t refuse to show a man how to use a printer — is a vulnerable audience.

Often, discussions around sexual harassment in the workplace center on interactions between employees and supervisors. There’s good reason for this — supervisors have influence, if not outright control, over who gets hired and fired. In service occupations, however, keeping the customer happy is often as important as keeping management happy. The employee who doesn’t laugh at the customer’s joke, or takes offense to questions about her love life, is vulnerable to complaints to management. Folks who haven’t worked in service industries might be surprised at how quickly not laughing at a joke about what a customer wishes your uniform looks like can turn into complaints to your manager about your bad attitude; or how declining a date can turn into false allegations about your supposedly terrible job performance.

Usually these interactions occur within a limited window. You serve your harasser dinner, they’re inappropriate, but then — crucially — they leave. But what if the customer never had to leave? What if anyone could walk into your workplace, ask you as many questions as they wanted on virtually any subject, from the moment the doors open in the morning until they close at night?

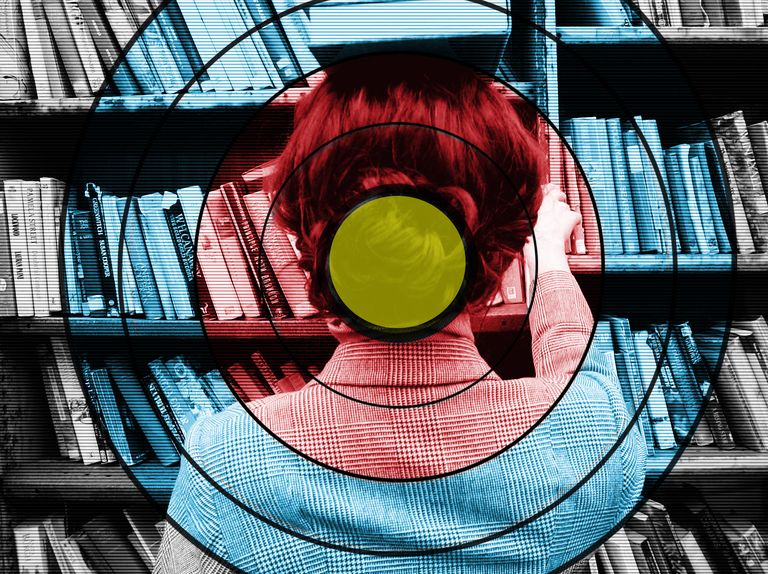

Public librarians are deeply committed to access. We believe the library should be open to all and we want patrons to feel comfortable asking for information about almost anything. You want information about sexually transmitted infections? No problem. Books on tantric sex? Right this way. We stay open, friendly, and approachable because we want you to know that we won’t judge your information needs.

But this also makes our jobs a fertile ground for sexual harassment. Technically, there’s no reason a patron can’t sit at an empty table and stare at the librarian all day, ask for help setting up an online dating profile, or print out explicit material. In many cases there’s nothing wrong with the aforementioned behavior, and that's what makes our situations tricky. Librarians fiendishly guard patrons’ right to do everything that makes sexual harassment so prevalent in public libraries — right up to the point where it becomes harassment.

There is a gender component to sexual harassment in libraries that’s impossible to ignore. Librarians are disproportionately women (in 2015, women accounted for 83 percent of all librarians) and while sexual harassment can happen to any gender, it’s frequently perpetrated against women. As Kelly Jensen, a contributing editor for Book Riot and a public librarian, says, "When you work in a public facing job, no matter what, the liability is that you're female." Women of color and LGBTQ folks experience particularly high rates of harassment. Couple that with all librarians’ (regardless of gender) eagerness to help, and it’s not hard to see how the line between having access to information and having access to the librarian giving it to you is thin in some people’s minds. Sometimes it feels like men view librarians as the "Mad Men"-era secretaries they never had.

Library management varies widely when it comes to enacting policies to handle these situations. The American Library Association doesn’t provide any guidelines or resources for dealing with sexual harassment, either from patrons or colleagues. Without that guidance, it’s up to individual libraries to create policies for dealing with patron harassment.

In any workplace sexual harassment scenario, it’s not just enough to make employees aware of the policies that protect them. Management also has to back up those policies by taking action when necessary. This does not always happen. I discovered this firsthand when I went to report a library patron’s escalating harassment to my boss. As I recounted this latest round of inappropriate behavior, my boss asked, "Well, how old is he? Is it possible you’re just..." My boss trailed off, seeming to imply that I was simply overreacting about an older man who didn’t know he was being inappropriate.

In my experience, and the experience of many other librarians I know, management is often reluctant to address the problem of sexual harassment — especially if it’s verbal and not physical — for fear of generating any negative attitudes about the library. Public libraries are dependent on the public valuing them; when a beloved branch has been on the verge of shutting down it is often the patrons (perhaps even those patrons who have engaged in harassment) who rally together to keep us open. It’s residents who approve and pay taxes that keep libraries alive. I understand this. It’s why I spent so many years gritting my teeth through comments about how I’d really look the "sexy librarian" part if I only had glasses.

Without formalized standards and a proactive management, librarians do what folks who are vulnerable to harassment have always done. We whisper, we warn. We stop the patron who’s intent on chasing the librarian into the staff room. If we happen to see it. If the library is fully staffed. If he can be stopped.

Good librarians are alchemists who turn libraries from a building with books and computers into a vibrant hub of information and exploration. Libraries need these passionate, dedicated people to want to stay with them. And so it’s time for the American Library Association to recognize and address the reality of sexual harassment in libraries. It’s time for library management and the city and county governments they’re affiliated with to unequivocally stand behind librarians’ right to serve the public free from physical or verbal sexual harassment. Librarians support our communities and it’s time we demand that they are supported in return. Our #TimesUp moment is long overdue.

Katie MacBride is a freelance writer and the Associate Editor of Anxy Magazine. Her work has appeared in Rolling Stone, LitHub, The Outline, and New York Magazine, among other publications. You can follow her on Twitter at @msmacb and find her work at www.katiemacbride.com.