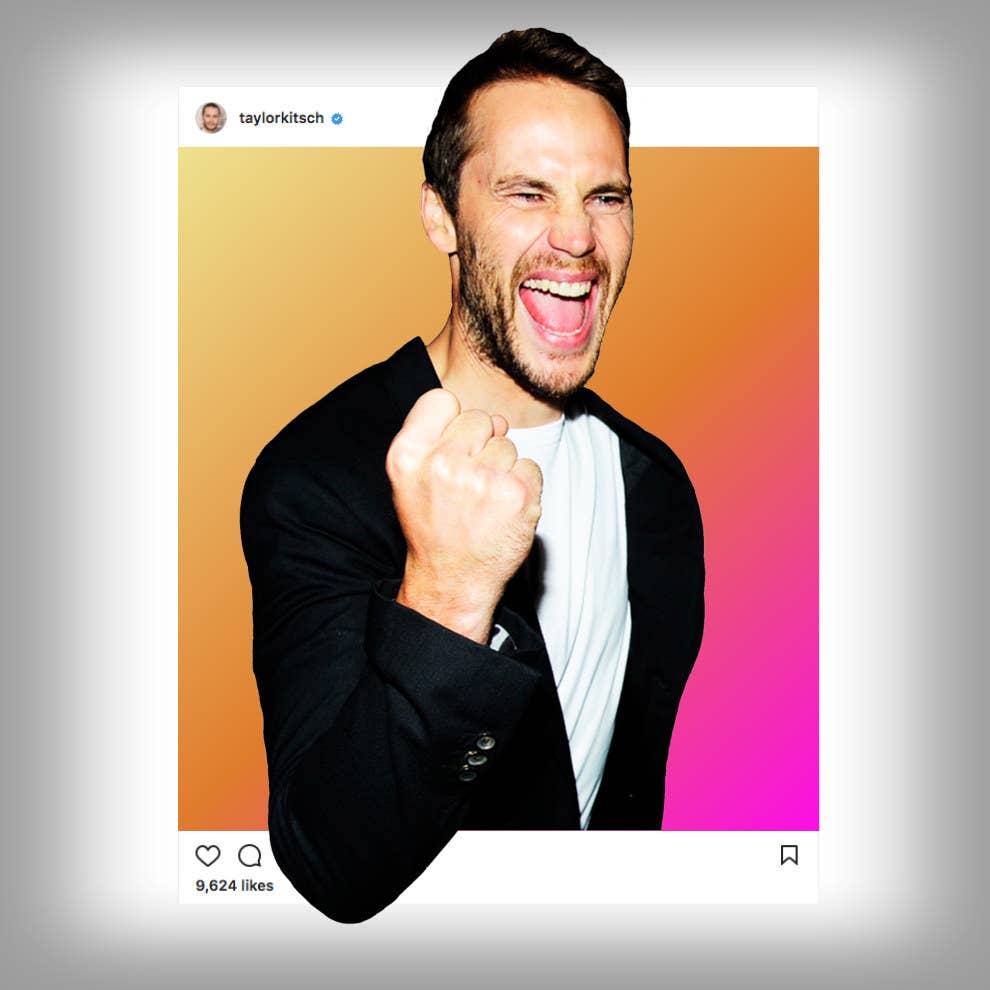

On January 19, Taylor Kitsch made his first Instagram post. Since then, he’s posted 39 more — an utterly charming mix of childhood photos, oversaturated glamour shots, and landscape appreciation. Instagram Taylor Kitsch feels very much like the sort of guy who, as he once told Interview, was “voted funniest guy in the school twice.” Dad humor meets deadpan, with captions on an old photo of his beat-up car like this:

“Best $1200 ever spent. Dug ditches to get. Drove down to LA. Turned into my home.Delivered cookies.The paint color has never been duplicated. Engine ran off of orange marmalade and auditions I bombed. Racing tires are self explanatory.It also had a full California king bed in back. Rain shower/steam. Washer/dryer.

And I’m legally not allowed to tell y’all what was under the hood. Sound system casually made ears bleed.

0-250 in 3.65sec(in snow).

Forever grateful for that Pontiac Firefly...the Grind is the best part.”

Instagram Taylor Kitsch loves his motorcycle, loves the Canadian ice dancing team, loves remembering what he’s learned from various long-lost film roles. He drops G’s (“Ridin’”) and approximates his mom’s Canadian accent (“G’head. Try ‘Em on.”). He regularly responds to commenters. He’s nostalgic and romantic about the world around him. He’s mostly a loner. He was an adorable child. And, periodically, there’s a feeling that he wants to punch the other version of himself — Movie Star Taylor Kitsch — in the face. It’s all perfect, or at least it’s perfectly in line with how I want to imagine Taylor Kitsch.

With his Instagram, Kitsch is doing something fascinating, with a high level of difficulty: He’s rebuilding his star image out of the ashes of a failed one. What’s all the more remarkable is that he seems to be succeeding at it without any PR supervision.Which might, of course, be part of the reason it works so well.

In 2012, building on the success of Friday Night Lights — a beloved show, but watched by relatively few — Kitsch embarked on what was supposed to be a massive, star-making second act. He was going to be the next action superstar, a taciturn hunk, Bruce Willis meets Jason Statham. Or something like that. Instead, he got cast in two bloated film wrecks — John Carter and Battleship — both of which were released in 2012 and both of which massively flopped. The publicity leading up to the films all asked the same question: Is Taylor Kitsch the next big thing? The answer, it seemed, was absolutely not.

While both films failed for reasons that largely had nothing to do with Taylor Kitsch, the Taylor Kitsch, Movie Star Campaign train had the left the station. And once in motion, it was impossible to stop — even if the engine was on fire and the tracks were disappearing. Savages, a 2012 Oliver Stone film that mostly required Kitsch and Blake Lively to be sweaty and hot together, barely broke even; Lone Survivor did well, but Kitsch was secondary to both Mark Wahlberg and Eric Bana. His attempts at small-indie counterprogramming — like The Grand Seduction, whose primary appeal was Kitsch in wool cowl-neck sweaters — barely made a blip outside Canada.

Kitsch was praised for his performance as Bruce Niles in The Normal Heart (2014), but his film career had effectively disappeared. Even a turn on the second season of True Detective in 2015 — a series whose first season was responsible for the so-called McConnaissance — couldn’t change the narrative that had collected around Kitsch’s career, in part because the entire season was universally acknowledged as overwrought garbage. The Taylor Kitsch Is Going to Be a Star train wasn’t just on fire. It was a smoldering wreck.

How did it happen? The question was rehashed with each new profile that accompanied each new attempt to place Kitsch firmly on track: John Carter was a disaster in the making; Battleship felt like the board-game-turned-into-movie that it was; Savages was, well, a contemporary Oliver Stone film. But none of these stories, which usually dedicated a quick paragraph to Kitsch’s failures at stardom in making the case for why this new project would be his grand ticket, quite pinpointed the real crux of the problem.

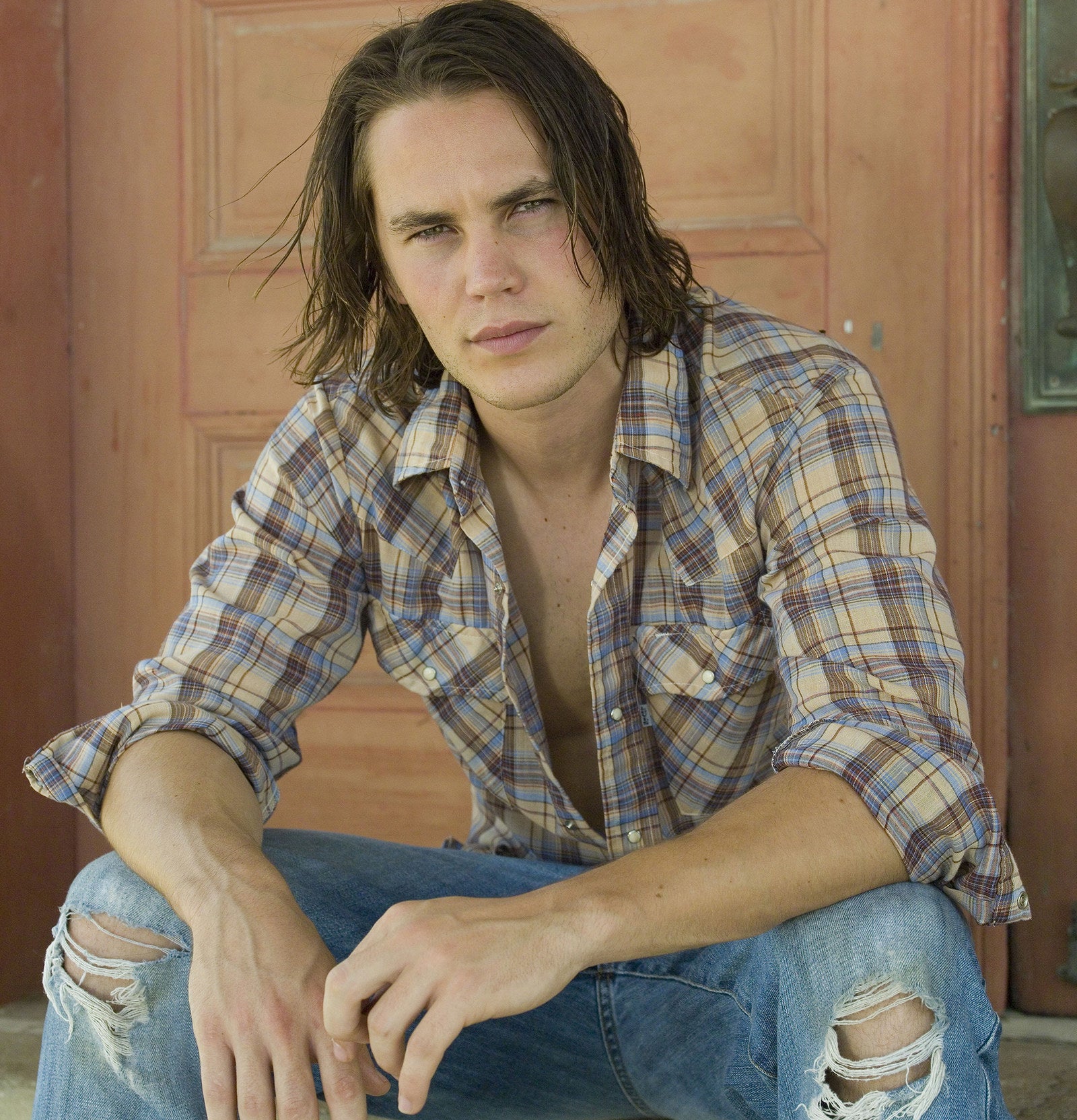

Kitsch failed to become a movie star because his movie-star image — as one-dimensional brooding hunk — was boring. It ignored the parts of his onscreen performances and offscreen persona that made him interesting in the first place. It forgot, or elided, or failed to emphasize: Taylor Kitsch isn’t just hot. He knows he’s hot, and finds that fact — and the conversations around it — deeply hilarious.

Publicists, managers, agents, profile writers, maybe even Kitsch himself, all seemingly forgot that Kitsch is funny. He even told Interview as much, when asked if he’d ever do a comedy: “I’d love to, it’s just got to be the right one,” he said. “When I work, I take it super-seriously, but when you get to know me, man, I’m not, I laugh as much as possible. Growing up, I was that guy at school getting kicked out of class every day to make someone laugh.”

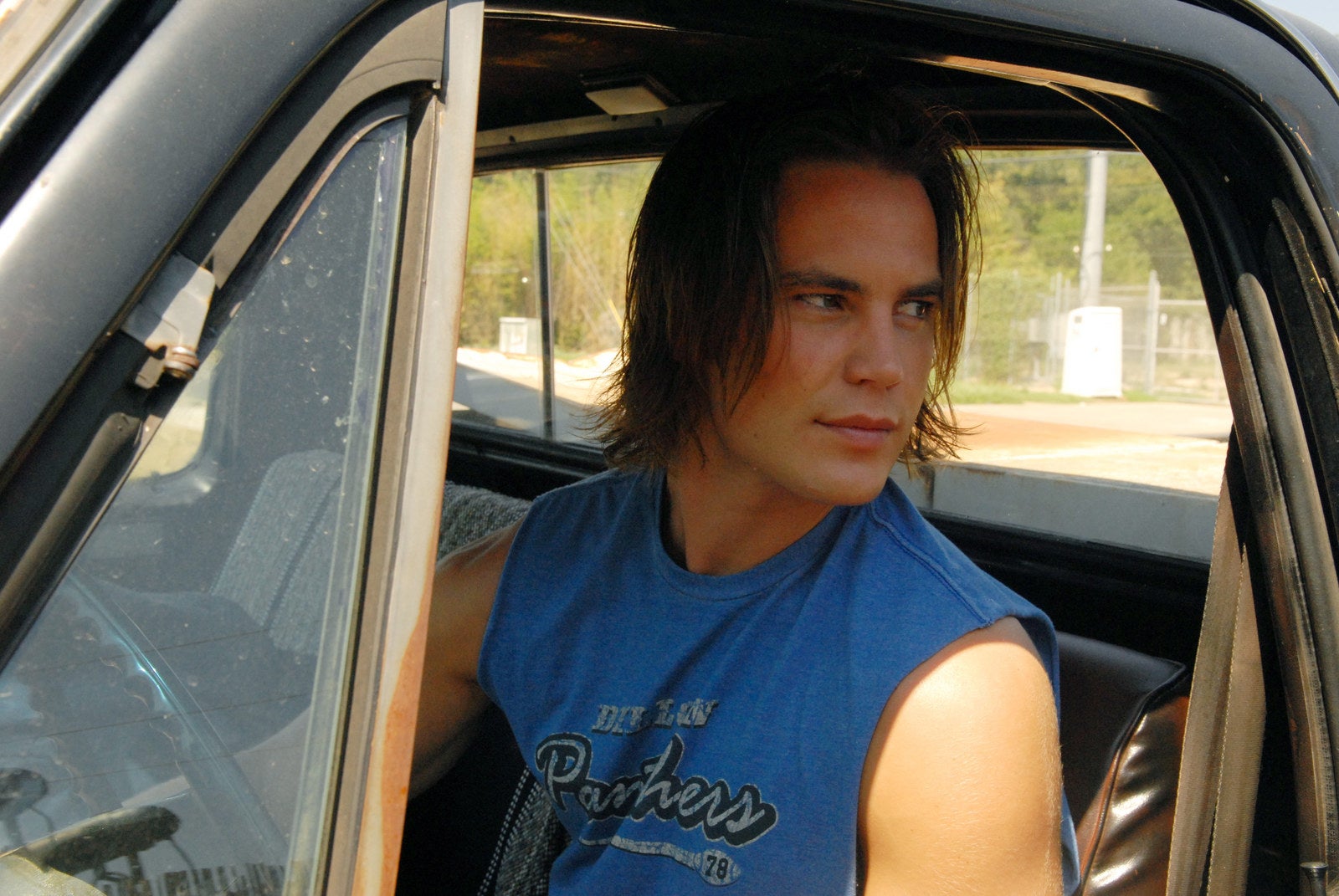

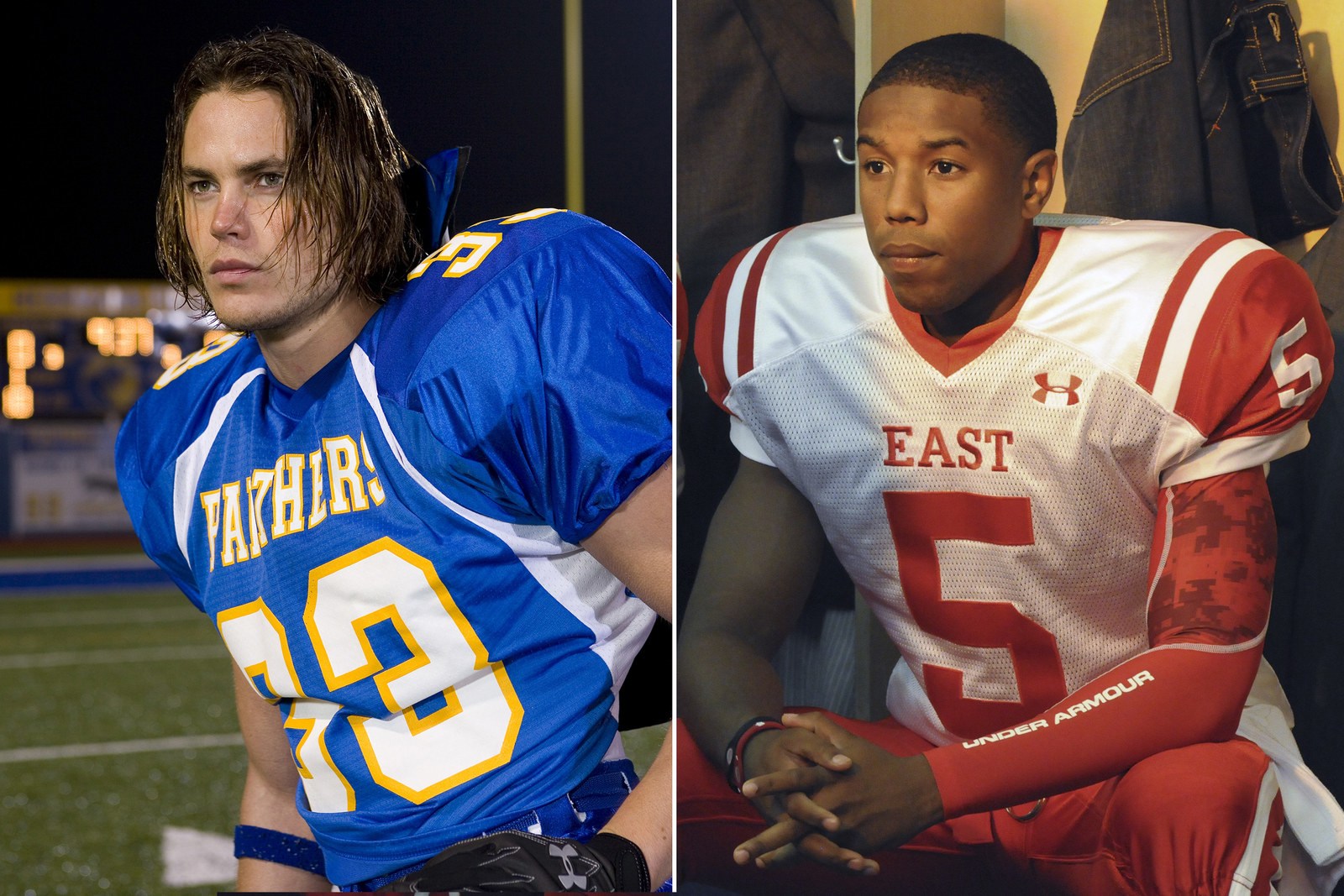

If you love Taylor Kitsch, you know that he’s funny — because if you love Taylor Kitsch, you almost certainly fell in love with him on Friday Night Lights. Like all the male characters on the show, Riggins was tender, masculine, flawed, and deeply American. Over five seasons, Kitsch convinced audiences that the brooding, self-satisfied high school fullback contained multitudes: that he was at once tragic and dim, caring and self-effacing, charismatic with a sort of visceral, animal sex appeal that makes you embarrassed to be lusting after a teenager (a twentysomething playing a teenager, but still). His teammate, Matt Saracen, is cute; Riggins, by contrast, is hot. You want to mother him one moment and fuck him another, which is at once confusing and deeply compelling.

That Riggins is also hilarious — in an almost inexplicable way, one that hinges on confidence but is never bombastic, or self-aware — only enriches the attraction. (Peak Riggins humor: when he tells his infant nephew to “Keep your guard up, stay angry.”) At the time, Kitsch was so good at playing Riggins that it was easy to extrapolate that Kitsch himself was Riggins-esque: He had been essentially unknown before the role, so whatever details you learned about his life (he grew up in a trailer park in British Columbia; he played hockey) were easy to map onto the Riggins character framework. What’s more, like the rest of the Friday Night Lights cast, he improvised most of his dialogue — Riggins-speak is Kitsch-speak.

As audiences, we have a remarkable inability to conceive of charisma as acting. Charisma is supposedly intrinsic, it just is, it is not the accumulation of acting decisions. Oftentimes, that’s true: A star can turn on their charisma, not just for performances, but in person, for interviews; they can transmute it in photos. Cary Grant is the apotheosis of this understanding, but Tom Cruise was once spectacular at it, as was Will Smith. George Clooney is still good at it, Brad Pitt less so. Zac Efron is bad at it; so is Robert Pattinson. Chris Evans and Oscar Isaac are better. Channing Tatum has it when he dances. The Rock thinks he’s great at it, which means he’s just okay at it. Kitsch’s Friday Night Lights costar Michael B. Jordan might be the closest we have to a pure contemporary embodiment of the deeply charismatic male star.

At the heart of each of these men’s images was that beguiling appeal, that soft seduction, that thing that made you want to be around them and think the best of them — it allowed you to forget or ignore the gentle trickery of the Hollywood image machine.

And if Taylor Kitsch was destined for movie stardom, tapping that vein should’ve been the route: Find a role that’s not Tim Riggins but allows the essence of Riggins, the very root of his existing star image — the unexpected warmth, the charisma, the deadpan humor — to shine through. Play up those qualities in interviews. Maybe do an indie that suggests a slightly different, and darker, slant. Perhaps even star in a rom-com. But, whatever you do, don’t star in a massive and charmless green-screen franchise in the making. Unfortunately, every star’s publicity and management team seems to have internalized the same logic: that there’s no such thing as a bad blockbuster starring role, even when literally decades of history, riddled with the wreckage of would-be stars’ careers, suggest otherwise.

By the time Kitsch attempted to move away from those would-be blockbuster roles, their failures had already enveloped him. He was no longer a star-to-be, but an also-ran whose career was in rehab. That failure shadowed everything written about him, and overdetermined every performance he gave afterward. Meanwhile, Michael B. Jordan — who’d moved on to another television role (in the equally beloved Parenthood) and then to indie acclaim in Fruitvale Station, before gradually making the move to franchise films — made the good choice to keep working with a director (Ryan Coogler) who knew how to hone his greatest strengths.

Stardom is, at least in part, about picking an image and sticking to it. But even in Classic Hollywood, the studios would “test” a potential star in different types of roles and different images, before landing on the one that clicked, that resonated, and would launch them into something larger. Cary Grant himself spent years as a somewhat boring, slightly slimy nothingburger before his studio pinned him as a dapper screwball comedian; Clark Gable was marketed as a high-society ladies’ man before he became a swarthy outdoorsman.

Taylor Kitsch didn’t need that sort of market testing; the blueprint for his potential stardom — the hunk with a sense of humor — was already there. It was just ignored, or at the very least flattened, by the sheer mass of the projects he took on.

After the critical failure of True Detective Season 2, Kitsch gradually receded from view. In 2017, he was billed fifth in both American Assassin and Only the Brave — neither of which broke $70 million. (His role as a hotshot firefighter in Only the Brave is the first to truly tap his Riggins-esque charm, but the film utterly failed to find an audience, grossing just $18 million of its $38 million budget).

But as those films hit theaters in 2017, Kitsch had already made the decision to embrace the last-ditch effort of would-be stars: a juicy, risky, transformative performance on extended cable. In this case, Kitsch transformed into David Koresh, the leader of the Branch Davidians cult who, along with 76 followers, died after a prolonged standoff with the FBI in 1993. This part in Waco is the sort of role that Kitsch could’ve/should’ve taken after Friday Night Lights — one that plays on his charisma, his association with Texas, his gravitas, but manages to twist, darken, and complicate all of it. It’s a role that expands his existing star image instead of abandoning it.

In anticipation of Waco’s release on the newly rebranded Paramount Network — formerly Spike — Kitsch embarked on a different sort of publicity tour, operating without a publicist. (Kitsch has a manager, but no personal publicist — a genuine rarity.)

The first big profile of the new Kitsch era appeared in Texas Monthly, a magazine that’s less glossy hotel-room publicity, more serious journalism and skillfully drawn profiles. It begins with a sentence that perfectly encapsulates his appeal: “Taylor Kitsch loves being Taylor Kitsch, and one of the charms of the 36-year-old actor is that if you meet him, you’ll love that Taylor Kitsch loves being Taylor Kitsch too.”

That sort of confidence, and general satisfaction, never shone through in the previous profiles — perhaps because their driving question was always “Is he going to make it? Is he?” That anxiety was also absent from Anna Peele’s GQ profile, released in January. It made passing and dutiful reference to his John Carter days, but the focus, the takeaway, was Kitsch’s overwhelming likability and goofiness: his self-mockery, his reliance on nicknames (he calls Connie Britton “Cons” and Kyle Chandler “Chands”), the way he takes Peele on a hike because he doesn’t want to wind up looking “like a bag of milk,” the fact that he comments on the “goodness” of passing dogs. Like the title of the profile itself — “Taylor Kitsch Forever” — the star image that emerges evokes his Friday Night Lights persona, but recenters it as authentically Taylor Kitsch.

And then there’s the Instagram account. Until this year, Kitsch was all but invisible online. He didn’t date famous people; paparazzi didn’t track him, in part because, after Friday Night Lights, he stayed in Austin instead of moving back to Hollywood. When seemingly all but the most massive of stars were establishing social media accounts, Kitsch rejected them. In 2014, he promised, “if anyone ever thinks I’m on Facebook or Twitter, it’s not me, for the record — it’s never me.”

Four years later, Kitsch launched his Instagram — complete with a blue “verified” checkmark. He uses filters the way most of us used them back in 2012: heavily, “artistically,” flagrantly. His posts on the app seem random but, taken together, follow a sort of organized logic. There’s a promotional photo for Waco: “Lil premiere action tonight,” he captioned the photo of himself in costume as Koresh, full mullett and ’90s glasses, flipping off the camera. Then a photo of him on a motorcycle, or taken from a motorcycle, or a picture of a motorcycle. (“Yellowstone. Top 5. Nothin’ beats it….”) Next, a picture of him as a kid, then one highlighting the work of African Children’s Choir — an organization he volunteered with last year.

Occasionally, there’s a shot from one of those recent magazine profiles or, last week, a screengrab letting fans know he’d be on Trevor Noah’s show. But the best posts, the ones that distinguish his Instagram from hundreds of other stars’, the ones that endear him to the 78,000-plus fans who have followed him over the last month, the ones that just slay me, are his merciless self-owns.

There’s the one of him in a field of tall, golden grass, wearing a suit, his hand on his face in an unnatural yet somehow devastatingly handsome way: “Excited to be first to post a magic hour shot on Instagram.”

Then there’s a picture, maybe doctored, maybe in a fat suit, of Kitsch in a version of his costume from the massive flop John Carter — which, to be clear, he’s definitely not shooting a sequel to:

“Day 3 of JC2! Pumped to be back. Lil carb-load/cat nap before some wire work. Short 421 day shoot. 6 day weeks.Feel sharp..mark the calendar summer 2022!!”

Of course, I’m not naive enough to believe that Kitsch’s Instagram — or any Instagram, star-created or not — is not a curated vision of his life and who he is. But celebrity social media’s most beguiling quality is its ability to convince us that the star himself is controlling the narrative: that the images before us, and the overarching understanding they create, reflect the star’s authentic self, or, at the very least, the way the star thinks of himself and his image, as opposed to the way a publicist and studio think of the star and his image.

Kitsch’s Instagram works because it doesn’t feel like a desperate attempt to make himself relevant again. It feels like a reclamation.

Whenever I write about a star who’s disappeared, or underperformed, or gone out of popular favor, I think about an interview that Julia Roberts gave, back in the late ’90s, ahead of the release of My Best Friend’s Wedding. It was framed as her comeback role after a string of bitter disappointments — movies like I Love Trouble, Michael Collins, and Mary Reilly, that called her to physically play against the Pretty Woman type that had launched her to stardom. For My Best Friend’s Wedding, she’d finally returned to form. “My hair is a lovely shade of red and very long and curly the way you guys like it,” she told People. “Please see this movie!”

With her hair, with the film choice, in the interview, Roberts was declaring herself recentered: I’m back to the way you fell in love with me, she could’ve said. Please see this movie! There was no Instagram or social media in 1997, so an interview, mediated through a magazine, was the closest you could come to revamping your image. Like so many other traditional forms of publicity, those sorts of cultivated interviews felt, and still feel, like a whap over the head, declaring I’m back! or I’m different! or I’m sorry!, sometimes in so many words, other times through photos and headlines and framing. They’re blunt publicity instruments — and often ineffective, inauthentic ones — especially compared to gradual, subtle accumulation of meaning that accompanies the best celebrity social media.

Waco isn’t the big hit those early, anxious profiles of Kitsch were waiting for. But in the end, Waco’s middling ratings matter far less than what the role and Kitsch’s embrace of social media have enabled: a gut renovation of his image. Not a redo, but a return, as it were, to the studs (lol), the very foundation of what made Taylor Kitsch seem like a star in a first place. Without a publicist, without even the option of a superhero movie, with a filter-heavy Instagram account and an empty “Future Projects” tab on IMDb. I can’t wait to see what he builds next. ●