Unless protect yourself, as soon as you open up an internet browser, you begin to leave digital footprints behind you that the sites you visit can use to track your activities and recognize who you are. We’re not talking about some crazy government data mining operation. This is totally legal, above board tracking done by the sites and services you use every day. Data collected includes your current location, which links you’re clicking on, whether you’re on desktop or mobile. And that’s just the beginning.

What your browser reports

The information leak starts with your browser, which reports various bits of basic data to the sites you visit by default. As soon as you appear online, for instance, you start reporting an IP address, your particular entry point to the internet, which can be used to approximate your location.

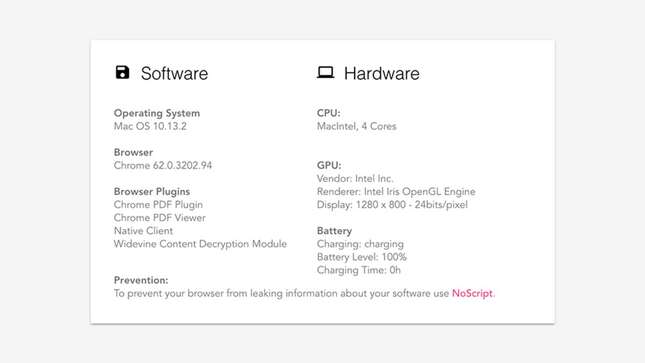

Your browser also reports its name, so sites know whether you’re a Chrome devotee or a Firefox user, as well as information about the computer system it’s running on, including your desktop or mobile OS, the CPU and GPU models, the display resolution, and even the current battery level if you’re using a laptop, tablet, or phone.

To see some of this data for yourself, open up the Webkay site and scroll down. If the Webkay site can read this information, so can any other page on the web.

Sites can also choose to monitor your inputs much more closely. To see some of this tracking in action, head to Click, which will report your mouse movements, mouse clicks, and other browser actions back to you.

These nuggets of data are just the first that help sites identify who you are. Your browser revealing that you’re running Microsoft Edge from somewhere in New York doesn’t tell a website much about you, but it can be combined with other data points to pick you out from a crowd.

Open up the Panopticlick test from the Electronic Frontier Foundation, and you can learn more about how your browser can broadcast a unique fingerprint to the web—your very own specific mix of browser software, hardware, default language, even the fonts you have installed—which can identify you even without any other information.

In other words, it’s unlikely that anyone else is using your special combination of monitor color depth, screen size, combination of browser plugins, and so on. Even if you haven’t typed in a single personally identifiable piece of information, a website can make a good guess about whether you’re the same guy who swung by last Tuesday, and can market you some relevant advertising accordingly.

Browser-reported data is just the beginning. The next layer is the data sites can gather for themselves.

What sites can collect

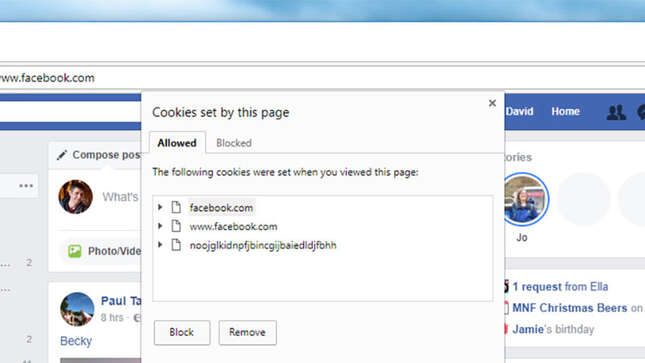

Most sites are very keen to find out as much about you as possible, whether to personalize their services to you or to target you with advertising. To help log this data, they’ll usually drop what’s called a cookie on your system when you turn up for the first time—these cookies are little files that act as markers to identify you.

Like breadcrumbs in a forest, they tell a site that you’ve been there before. They can also hold little bits of data: A cookie might save you the trouble of having to pick a particular city every time you visit a weather website, because the site knows what you picked last time; a cookie can also store items in your shopping basket so they’re still waiting for you when you come back days later.

This is all very useful for sites and users alike. But cookies can go further and help to add more and more pieces to that personal profile puzzle that first started to take shape with the data reported by your browser.

Browser security protocol dictates that sites can only access their own cookies—a fairly essential safety measure—but you also have what are called third-party cookies, which aren’t associated with a particular site but get injected across multiple pages through ad networks and other tracking technologies.

It’s these cookies that result in you seeing ads for fishing gear for a whole week just because you opened up a fishing website a couple of times, and it’s these cookies that Apple is fighting hard against in the latest version of its Safari web browser, much to the chagrin of advertisers.

Fundamentally, this is all being used to recognize who you are and better target advertising. Data from website visits, searches, cookies, and your browser is put together with some educated guesswork to try to figure out the ads you’re going to be most interested in seeing.

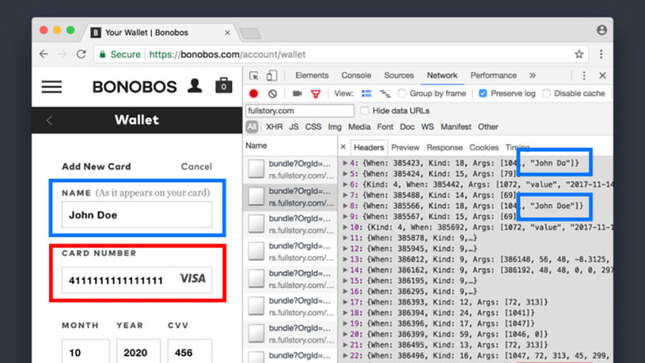

What’s more, a recent study from Princeton University found that cross-site trackers embedded in 482 of the top 50,000 sites on the web were recording virtually all of their users’ browser activity for analysis. These recordings are ostensibly for the purpose of website management and optimization; but while sensitive information is supposedly redacted from them, it’s another case of users having to put their trust, and their data, into the hands of third-party companies.

And another group of firms are adding to this pile of data: Our internet service providers, which can now make money by selling your browsing history, letting advertisers know where you’ve been and what you’re interested in. None of this data works in isolation, with marketing firms trading details and combining details to put together a very detailed profile. And it gets even more detailed...

Other information you’re giving up

So far, so much information, but we haven’t yet talked about the data you’re giving up voluntarily: The searches you run while signed into Google, the venues you check into while using Facebook, the date of birth details you give to Twitter, and so on.

Sites have their own privacy policies about how this data can be used—usually to target you with advertising, and maybe to improve the actual products and services at the same time—and the usual deal you make is to put up with this data collection if you want to use the services in question.

So if you feel like you must have a Tumblr account, for example, then you’re essentially giving Tumblr permission to monitor everything you do on the network. That’s partly just common sense, so that sites can police user behavior and fix bugs, but it’s yet more data to add on top of everything else we’ve talked about

Add all of this personal information together with the data that’s already been harvested from your online sessions, and the biggest operators like Google and Facebook can easily know you better than you know yourself.

Last year Google amended its privacy policy so that data from its DoubleClick ad network could be merged with the other data it knows about you—like your name and your favorite YouTube channels—to build up a very comprehensive picture of you and your tastes. Not every company has the reach of Google or Facebook, but data can be easily bought and sold between firms specializing in this kind of profiling.

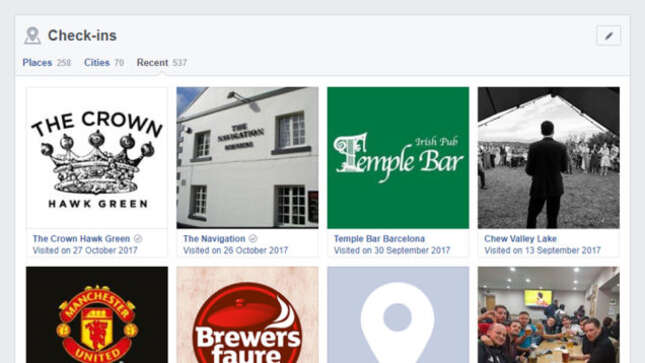

On Facebook alone you could well be revealing who your closest friends are, the places you like to visit most, how often you order pizza, and the top bands living or dead that you’d want to put in your dream gig line-up.

Thanks to the information you offer up to Facebook, and the data it collects as you browse, it knows when you’re expecting a baby, who you’ve worked for in the past, which way you probably lean politically, the times of day you like to browse the internet, and more besides—you can see some of the information it thinks it knows about you by visiting this page.

The world’s biggest social network might be an outlier in terms of how much personal data it can tap into, but the principles are the same on other sites, whether it’s ones you use for shopping, or travel, or reading the news.

It’s really down to the privacy policies of each individual site as to how all of this collected data gets logged and used, if at all. And while these policies are usually easy enough to access, they’re generally couched in very broad terms that give sites a lot of leeway when it comes to handling the profiles they’ve built up on you.

What can you do

Data collection at its core is not malicious. Websites need data to make their products better and to sell you the advertisements that keep them afloat. That said, you should be conscious about what you give up and to whom. For more on that, see our companion guide on how to avoid tracking as you browse the web.

This story was produced with support from the Mozilla Foundation as part of its mission to educate individuals about their security and privacy on the internet.