It's just after 8 on a crisp morning outside Besters, a farming village in South Africa's KwaZulu-Natal province, and Mhle Msimanga is wading through his herd of cattle in a wire pen, calling out directions to his sons and nephews standing outside it. "The cows can't get out if you're all crowded at the gate!" the 48-year-old farmer yells, speaking the local isiZulu language. The boys move aside, and a few cattle trot out, meandering onto a dirt road that leads toward the low-slung mountains that spread out behind Msimanga's property.

It wasn't always his land. In 2005, the post-apartheid South African government bought about 1,112 acres from his former boss—a white farmer—and transferred the title deed to Msimanga and his fellow workers. It was part of a larger transaction in Besters that year: The government acquired over 34,590 acres from white South African farmers and transferred the ownership to nearly 200 black South African families, who, like Msimanga, had lived and worked on the land for years.

The deal changed Msimanga's life and rewrote the future of his children. In 1991, he went from earning roughly $18 a month on this land to owning it, as well as a large herd of cattle. "There is no money in being a worker," he says. "It's only now I see money for all the work I put in."

'Wake Up, My Friend. Our People Want The Land'

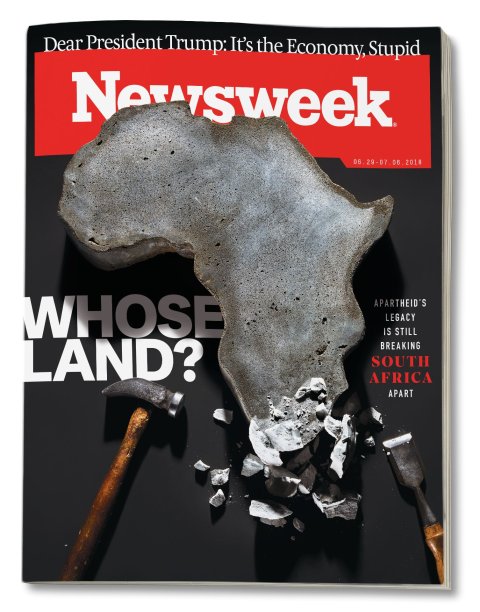

Land Ownership was supposed to be the reality for hundreds of thousands of black South Africans by now. But 24 years after the nation's first free elections, the country is still struggling to correct the gross injustices of colonialism and apartheid, the system of white minority rule and racial segregation.

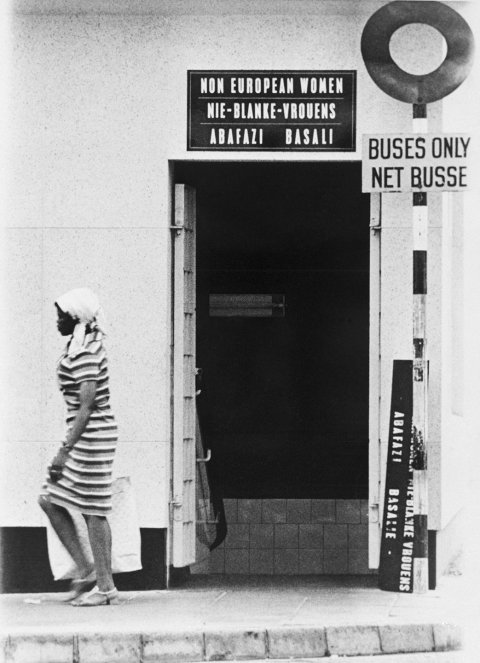

European colonizers arrived at the southern tip of the continent in the 17th century and for the next 200 years drove Africans off their homeland. A policy in 1913 allowed the white-run government to further strip away black-owned property. Those policies continued under apartheid, which began in 1948 and ended with the multiracial vote on April 27, 1994.

But the stark reality is that inequality remains. Black South Africans, who make up 80 percent of the population, own just 4 percent of the nation's agricultural land, according to the government. The nation's white minority owns 72 percent.

The architects of South Africa's transition to democracy in the 1990s envisioned a much different outcome: The post-apartheid constitution says the government must help citizens get better access to land. The African National Congress, which has been in power since 1994, now wants to transfer 30 percent of the country's agricultural land from white to black ownership. In addition to buying it from white owners and redistributing to black ones, the ANC runs programs to help people claim territory and firm up the rights of those whose tenure is insecure.

But apartheid's legacy has been difficult to dislodge, and many think land reform has been a disaster. To date, only 9 percent of commercial farmland has been transferred to black owners through claims and redistribution. The backlog to settle existing claims is 35 years; for new ones, there's a wait of well over a century. Many large agricultural reform projects have failed; success stories like Msimanga's are the exception. "You can move as many hectares of land as you want, but if you don't get them to be productive, then society's problems will remain," says Wandile Sihlobo, an agricultural economist for South Africa's Agricultural Business Chamber.

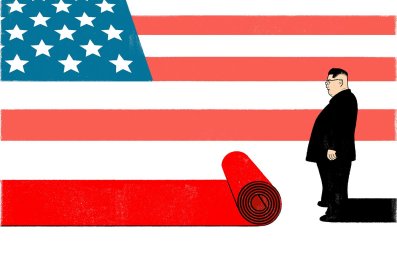

The slow pace of change has made land one of the most polarizing issues in South Africa today. With national elections looming in 2019, the small but influential Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) opposition group has tapped into popular frustration over the ANC's failure to address the problem. The party has been pushing the government to seize white-owned property without paying landowners, as former President Robert Mugabe did in Zimbabwe, which borders South Africa to the north. Critics of Mugabe's policy point to the period of economic collapse that followed: Food production dropped, due in part to a lack of equipment and training, and unemployment soared as thousands of evicted white Zimbabwean employers left the country.

The ANC, whose popularity plummeted under the controversial tenure of former President Jacob Zuma, declared in December it would use "land expropriation without compensation," as the process is known, to speed up reform. The party promised to do it without compromising the economy, food security or jobs. President Cyril Ramaphosa, who replaced Zuma this year, has repeatedly said the taking of land from the indigenous people was South Africa's "original sin," and that its return to its rightful owners will unlock the country's economic potential.

In February, Parliament overwhelmingly voted in favor of a resolution to pursue the expropriation policy and appointed a committee to investigate whether the constitution needs to be amended to do it. The committee is due to report back on its findings later this year, before the 2019 elections.

Unsurprisingly, the prospect of state-sanctioned land seizures has spooked white landowners in South Africa. Media coverage of "land invasions" has increased across the country, where black South Africans have moved onto unused, privately owned property and claimed the right to live there. "Once it becomes a free-for-all, how are you going to stop millions of people from lawlessness?" says Louise Rossouw, former regional chairperson of the Transvaal Agricultural Union of South Africa in Eastern Cape province. "It's crazy. People are already starting to talk of civil war. "

The ANC has tried to stamp out fears that South Africa's economy is going to crash like Zimbabwe's. It has emphasized that unused land would be targeted first, but party leaders have also doubled down on their original pledge. "For people who think that the issue of land in South Africa will be swept under the carpet, I say, 'Wake up, my friend,'" Ramaphosa recently said in Parliament. "Our people want the land."

'We Haven't Been Able to Recover'

Msimanga's homestead in Besters sits off an unpaved road. His property includes five modest buildings, homes to a dozen members of his extended family. Sitting in his living room, on a couch covered in plastic, Msimanga looks slightly ill at ease in his ripped jeans and dusty work boots, as if he'd rather get back to his cattle. Above his head, an embroidered mat hanging from the ceiling reads, "All I Have Is a Gift From God."

He says he supports the government's revived commitment to make more black South Africans landowners. In the country's bleak job market—about 30 percent of black South Africans are unemployed, compared with 7 percent of whites—farming would provide more security for his kids than sending them to university. "I can spend my money investing in the land that will help my children and their children," he says. "This is what a black man can do with this opportunity."

But the land reform project that Msimanga and his family took part in 13 years ago was different from the seizures being debated today. Back then, after several farmworkers lodged claims in the area, all the parties—20 white landowners and 199 black households—reached an agreement to transfer ownership of more than 20 percent of the land in Besters. The government bought that property from the white farmers at market value—some 14 million rand, or $2.5 million at the time. Nearly 80 percent of the area remained under white landownership, and it still does today. The deal also provided government funds to help the new farmers get started. Msimanga, for instance, received a few dozen cows to go with the one he already owned, which have grown into a herd of 380.

Not all the black workers involved in the deal have fared so well. A few miles away, on a collectively controlled farm, one of the owners explains that a lot of their cows died in a drought a few years back. "We haven't been able to recover," says Jabulani Mavimbela. The business is "progressing," he adds. "I can't say I'm totally satisfied, but it's progressing."

To supplement his income, Mavimbela still works on the sprawling farm of Roland Henderson, a white farmer in Besters. Standing in the living room of his large stone-walled farmhouse, Henderson points to a portrait of his great-great-grandfather hanging on the wall. His family has owned land here for five generations, and Henderson continues the family business. In 2003, he became one of the main negotiators of the land transfer on the landowners' side.

Henderson, the chairman of the Besters Farmers Association when black farmworkers made land claims in the area, says the white farmers knew they "needed to do something." Since this was one of the country's early large land transfers, the two parties had to figure it out as they went along. The association and the farmworkers had a series of long discussions about how the transfer should take place, and they jointly formed a company that applied for and received government funding earmarked for these kinds of transactions. "It was right after independence, and there was baggage," he says. "We essentially learned to trust each other. There's nothing more important than that."

There's a reason trust didn't come easily. Under apartheid, 85 percent of South Africa was reserved for whites to live in and own. In a move reminiscent of American treatment of Native Americans, the white-minority government carved most of the rest of the country into 10 "homelands" where the black South African population—millions of people belonging to nine distinct ethnic groups—were forced to live. The government called this new country a racially "separate but equal" state, but the homelands were brutal places. The living was cramped, services were poor, and the unproductive agricultural land in the "Bantustans" made farming largely untenable, turning the areas into pools of cheap labor for white South Africans.

It's no wonder, then, that Mavimbela says he and other farmworkers were skeptical when the proposal for the transfer first came up. "We didn't take it seriously," he says. "What if we left our jobs, and the government didn't give us land?" Years later, he doesn't think the plan went perfectly, but one of his daughters has recently graduated from university. "I wouldn't have been able to send her as a farmworker."

'The Situation Is Very Dire in South Africa'

South Africa is now the most unequal society in the world, according to the World Bank. And the inequality has worsened under democracy. More than half the population lives below the national poverty line. The shortage of housing in big cities like Cape Town and Johannesburg is severe, with many people waiting for public housing and stuck in informal settlements without access to regular water and electricity. Public schools and health clinics are understaffed, and unemployment is dire.

The ANC's failure to deliver on the promises made during the freedom struggle that Nelson Mandela helped lead—including equality and the rights to work, land and housing—has sent the party into political crisis. The EFF, headed by the charismatic and controversial young politician Julius Malema, has made the government's slow progress on land reform one of its prime targets. "When we say to the people of South Africa 'Occupy the land,' we don't say do an illegal thing," Malema said in a speech in April. "It is the right thing to do, because it is your land."

Though the ANC has always supported land reform, Malema's militant rhetoric—along with the ANC's falling support among voters—has pushed the party into embracing the controversial policy of expropriation without compensation.

As a result, in agricultural towns, white landowners are waiting to see what happens next. In the Eastern Cape, some have stopped investing in the infrastructure around their farms, like roads, fences and dams, says the Transvaal Agricultural Union's Rossouw. "If you have farmed as long as I have, it's unmistakable what is going on," she says. "Nobody knows what to do."

Rossouw thinks that the notion that farming can solve South Africa's problems of high unemployment and poverty is "a fundamentally flawed concept," and that the government should focus instead on job creation and building more housing. "It's like telling an entire population, 'We'd like you to all become astronauts,'" Rossouw says. "Why must everybody be a farmer? You're dictating a lifestyle to a population."

The specter of land expropriation has also rekindled old fears among some fringes of white South African society that the policy could increase violent attacks against them. In March, Peter Dutton, Australia's home affairs minister, suggested his country should offer refuge to white South African farmers due to the threats they may face at home. (A month later, the Australian government denied one such asylum request, calling it baseless.)

In May, members of AfriForum, a South African group that represents some Afrikaners, went to the U.S. to lobby policymakers about farm attacks and to warn of the dangers of the government's plan for expropriation without compensation. "The situation is very dire in South Africa," Ernst Roets, the group's deputy CEO, said during an appearance on Fox News. "Whenever you speak out against this, there's serious backlash."

Others argue that the tactic simply won't work and could send the country into an economic tailspin. At the very least, the process would be an "extremely complex technical headache," Sihlobo, the agricultural economist, wrote in a recent paper for South Africa's Agricultural Business Chamber. For instance, many white-owned South African commercial farms are heavily indebted to both commercial banks and the government. If the government were to take over without paying the farmer, would it also pay off the banks to which the farmer owes millions of rand?

Expropriating land without paying owners could also negatively influence property values, hurting the beneficiaries of the policy. "If it negatively affects property rights, it negatively impacts investments," Sihlobo says. "That means that whoever gets to occupy the land will not see any gains going forward."

'Even Unlawful Occupiers Have A Right To Housing'

Ultimately, Sihlobo and some others think the government's focus on agricultural land as a target for transformation is misplaced. "There are farms that are empty if you drive across South Africa," he says. "Nobody goes and invades a farm. The demand for land is in cities."

That certainly seems true if you turn on the evening news. Since the debate heated up this year, the media have pumped up fear with relentless coverage of people trying to occupy empty tracts of land, almost exclusively in urban areas. The occupations, called "invasions" and "grabs," are taking place everywhere, from the dense neighborhoods of Cape Town and Soweto to upscale housing developments along the touristy south coast.

The claims tend to quickly devolve into clashes with police. In late May in Cape Town, cops fired tear gas and rubber bullets at crowds where residents have been occupying the informal settlement of Vrygrond for weeks. People point out that this kind of recurring conflict is reminiscent of the forced evictions that took place under apartheid, when millions of nonwhites were forced into barren land or overcrowded, underserved townships on the outskirts of cities. Now that they have the right to live in the cities, there is no room for them.

These occupations "are an expression of land demand," says Lauren Royston, a senior associate at the Socio-Economic Rights Institute of South Africa, a nonprofit human rights group in Johannesburg. "Even unlawful occupiers have a right to housing."

Just as the constitution mandates government efforts to secure land for more people, it also guarantees South Africans' right to "adequate housing." Today, authorities must obtain a court order and the state must provide alternative places to live if the people occupying a place, lawfully or not, are to become homeless as a result of their eviction. According to government statistics, 13 percent of South African households were living in informal housing as of 2016. With most South Africans now residing in cities, that means demand for urban housing is intense, and the government is struggling to keep up.

Though some groups, like the EFF, actively encourage illegal occupation, government policy supports only sanctioned takeover. But officials also recognize that occupations are "a reflection of the frustration of our people with the pace of land reform," Maite Nkoana-Mashabane, the minister of rural development and land reform, said in Parliament in May.

So far, the land debate has largely focused on agriculture, but, says Royston, if Ramaphosa's government is serious about speeding up the agenda, occupied urban property and buildings are an obvious place to start. "Land redistribution must surely begin where people are already living," she says. Otherwise, "the risk is that this is all only politics. And there are a lot of people that think that's what this is all about."

'I Could Have Done So Much More By Now'

As the tires burned in protests on the streets of Vrygrond in Cape Town, prominent ANC leaders met over two days in May in Boksburg, near Johannesburg, for a "land summit" organized to speed up the reform process. At the opening, Ramaphosa acknowledged that the ANC had yet to ensure more equitable access to land, chalking up the problem to weak government institutions, inconsistent legislation and misallocated resources.

But he also took a loftier view on why land matters as much in today's South Africa as it did during the colonial days. Quoting Canadian Mohawk activist Taiaiake Alfred, he said, "The voices of our ancestors continue to call out to us, telling us it is all about the land, always has been and always will be…. Get it back, go back to it."

South Africa is hardly alone in facing the daunting task of correcting historical injustices over land. The United States and Canada have struggled to address the enduring social and economic impact of the mass dispossession of Native Americans and First Nations people and have made little progress. There are success stories, in Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, for example, but more often mixed results. Though farm seizures in Zimbabwe have earned plenty of negative press, many scholars point out that the broader process has not been a failure, with small-scale farmers benefiting and production of some crops going up. As the situation there and in South Africa makes clear, these complicated resolutions can only begin to address generations of inequality.

In Besters, Msimanga stands outside his cattle pen, keeping one eye on his herd. The 13 years he's been the owner of this swath of golden grazing land have been a struggle. His expenses as a landowner are daunting. He needs more grass for the cows if he wants to keep expanding his business. And he can't help thinking about where he'd be if this had happened closer to 1994, rather than over a decade later. "If the government had started earlier," he says, "I could have done so much more by now."