No one saw this bull coming, so does Hang Seng Index have the legs to keep running in 2018?

Hang Seng Index has the strongest annual growth since 2009 while most analysts expect it can break historical record in the first half - but analysts have mixed view on the way ahead

Hong Kong’s stock market made its strongest advance in a decade, with the benchmark Hang Seng Index rising 36per cent to close 2017 at 29,919.15 points.

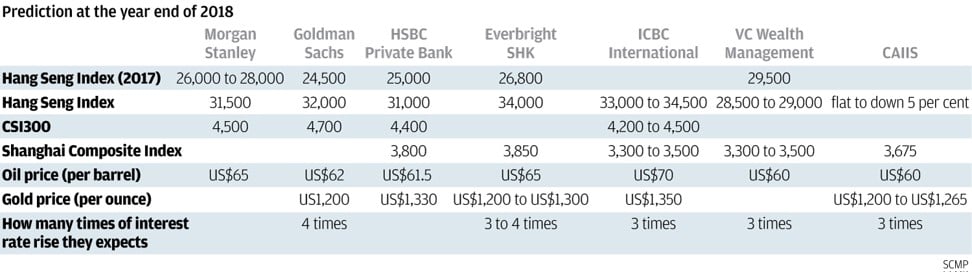

No one saw the bull coming. When 2017 started, the most optimistic forecasts from Goldman Sachs to Morgan Stanley to HSBC predicted that the main index of Asia’s third-largest capital market would close the year somewhere between 24,000 and 26,000 points.

Instead, the 51-member index broke through the upper forecast by mid-July, touching 30,003.49 on November 22, the highest level in 10 years. The China Enterprises Index, which tracks Chinese companies listed in the city, has risen 24.6 per cent this year.

Geely Automobile Holdings, the Hangzhou-based owner of the Volvo brand and a Hang Seng Index member since March, returned investors almost 266 per cent this year. Tencent Holdings, operator of China’s dominant social network, rose 114 per cent and briefly became the first Asian company to surpass US$500 billion in market capitalisation.

“Many international banks and brokers missed the boat this year,” said Christopher Cheung Wah-fung, chairman of Christfund Securities and the legislator representing Hong Kong’s financial services industry. “Fund managers who missed out on Geely and Tencent are the losers of 2017.”

China’s economic growth also stabilised at 6.9 per cent in the last three quarters, a slower rate than the previous 25 years, but faster than the most dire forecasts. That bolstered confidence, Cheung said.

Does the 2017 bull have enough strength to keep galloping next year? Yes, but not by far, according to the consensus of seven brokers, analysts and strategists canvassed by the South China Morning Post. The forecasts range from the most optimistic (a gain of 15 per cent) to the most pessimistic (decline of 5 per cent) to a median of a 5 per cent gain.

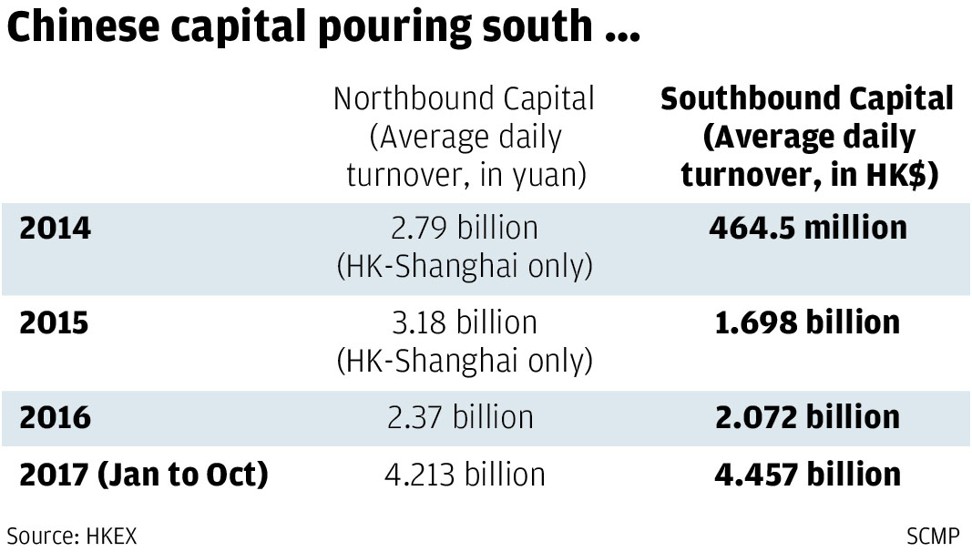

“Hong Kong’s market is a geared beneficiary of strong structural demand for overseas asset diversification of Chinese investors,” said HSBC Private Banking’s managing director Fan Cheuk-wan, who expects the Hang Seng Index to rise 4 per cent to 31,000 by the end of next year. The gains “reflect the 7 per cent projected earnings growth, stable China growth outlook and strong liquidity support from Chinese southbound flow,” she said.

“The rally would continue in the first half of 2018 but may turn south from the middle of next year,” he said.

Adding to the catalogue of market spoilers is the spectre of rising interest rates in Hong Kong, which the city’s monetary authority is compelled to follow in lock step with the US Federal Reserve to maintain the Hong Kong dollar’s peg to the US currency. The era of cheap money is long gone, and several more increases in interest rates have been foreshadowed for 2018.

“The pain of rising interest rates may also be reflected in the stock markets,” Tse said.

“The majority of good news may have already been discounted in the market, and macro factors such as nominal growth of China starts to moderate,” Lo said. “Tightening in global liquidity will drive up the cost of borrowing and eventually hit the profit margin.”

Mainland Chinese stock markets in Shanghai and Shenzhen are likely to fare better, as the government’s programme to cut debt and cap a runaway property market begin to bear results, while the selection of a new crop of leaders and top officials ensure enough political stability and certainty for the next five years, brokers said.

The Shanghai Composite Index, the key gauge of the bigger of the two Chinese exchanges, is likely to gain as much as 17 per cent next year, or remain little changed at its worst, brokers said.

“China will pull back on the deleveraging campaign in early 2018, which will boost sentiments, while rising corporate profits will help” bolster the stock market, said Stephen Innes, head of Asia-Pacific trading at OANDA, who expects the Shanghai Composite Index to advance 9 per cent to 3,600 by the end of 2018. “I expect more mergers, which will boost some companies’ stock value.”

Additional reporting by Laura He, Zhang Shidong and Josh Ye