Carl Donnelly was driving on Monday morning when his phone rang. He could not pick up, but when he saw who had called – someone who was friends with him and Sean Hughes – he guessed what was coming. He called back and learned that Hughes, just 51 years old, had been picked up from his home by an ambulance on Sunday night. On the way to hospital he went into cardiac arrest. He died shortly afterwards. It transpired that he was also suffering from cirrhosis of the liver.

Donnelly, a comedian who had been mentored by Hughes over the past decade and become very close to him, had been worried about his friend for months. “In this last year, I’d been telling him he needed to sort his life out. It came to a head in Edinburgh this summer. He showed up and – there’s no easy way to say it – he looked like a dead man walking. I went to see his first performance, and he shouldn’t have been on stage. After the first week, I told him he needed to cancel the run and go home and see a doctor. It was like he was waiting for someone to give him permission. I called him three days later, but he still hadn’t gone to the doctor.” Even so, as Donnelly notes, “to a lot of people who hadn’t seen him for a while, his death came as a shock”.

It needs to be remembered that Sean Hughes was not the man one saw on TV. The persona that made him famous in the early 1990s on Sean’s Show – the melancholic, wry, puppyish indie boy – was part of who he was, but only part. He was also arrogant, selfish, demanding and sometimes cruel. I know this because for several years during the 2000s, I was close friends with him. Then, a decade or so ago, he stopped speaking to me, because he felt I had not responded to his needs with sufficient vigour. In the past few years, we began speaking again – I went to see his shows, we texted, we saw each other a couple of times – but my being cut off was nothing unusual. “There was a long period where we were the closest people in the world,” says one comedian who knew him in his first flush of fame. “We’d go out five times a week, call each other three times a day. But everyone fell out with Sean because he always wanted them to be there for his purposes.”

It’s also worth noting that it is hard to get people to talk publicly about Hughes, precisely because so many people had bad experiences with him, especially women. Those who knew him talk of how he seemed to be looking for reasons to cut off people he loved: Donnelly recalls Hughes falling out with one of his oldest friends a few years back, and how he told Hughes that the other person had done nothing wrong, but this made no impression. It was as if he was afraid of intimacy, and this meant women would experience the absolute worst of him. No one I speak to will go into specifics – it seems not to be something people want to revisit – but dark mutterings among women who had relationships with him floated around like an ugly cloud, becoming visible again after his death.

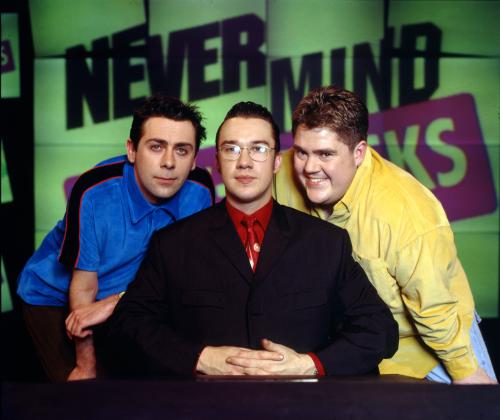

When I got to know Hughes, at the start of the last decade, he was at the peak of his fame. For 11 series, from 1996 to 2002, he was a team captain on Never Mind the Buzzcocks, the TV comedy pop quiz. He had gone from NME famous, known to a constituency of indie guys and teenage girls, to BBC famous, known to everyone. Famous enough that when he went to a pub in which he wasn’t a regular, he would insist on sitting at a corner table with his back to the room, because if he was recognised he would be pestered.

He was torn between desiring fame and wealth, and contempt for the way he had achieved it. He lived for the last 15 or so years in a huge and beautiful house in Crouch End in north London, paid for with the Buzzcocks money, but the thing that caught your eye as you walked in was a large print of Jane Bown’s portrait of Samuel Beckett: money and art, together. “Sean once said to me: ‘What I do is above comedy,’” says someone who worked with him on Never Mind the Buzzcocks. “I tried to explain that there’s nothing above comedy. He fell for this dark, lyrical poet stuff. All my friends are comics, and so many of them have been ruined by quiz shows.”

At times on Buzzcocks, you could see his disdain for what he was doing, even if it also made you laugh. Other, more telling incidents didn’t make it to screen: the time he was punched in the face before a show by Jah Wobble, who had been furious about the way Hughes had conducted an interview with him on London’s BBC local radio station GLR. Or him demanding to be set up to deliver a gag, then refusing to tell it. “I’m not going to do it,” he said, gesturing to his teammates – musicians rather than professional comedians – “because these fucking useless wankers aren’t joining in.” He wasn’t joking.

“Never Mind the Buzzcocks may have been the end for him. It was a great thing to do, but it wasn’t a great thing for him to do,” says one comedian friend. “It was the biggest thing he ever did, and Sean was unhappy about that.”

“I think he wanted to be an artist,” says his friend Stephen Jones, who records as Babybird (who also had the experience of being dropped by Hughes, and then reconciled). “Buzzcocks was just a paid job, but the seriousness was there in his books.” There had been a couple of collections of poetry and comic prose in the early 90s, and Hughes then tried his hand at being a novelist with The Detainees (1998) and It’s What He Would Have Wanted (2000). Both the acclaim and sales of his literary heroes eluded him, however.

He did the show, I think, because he loved music, even if it ended up disappointing him. But if Buzzcocks was the pay cheque, the radio show was where he indulged his delight in music and musicians. He was a loyal supporter of his favourite bands – Yo La Tengo, American Music Club, the Wedding Present among them – and a girlfriend of his once told me that musicians always saw the best side of him. Perhaps it was because it was one thing he was sure he wasn’t better at than them.

“Sometimes I had to steer him away from talking so much about the band, because it was a bit like doing an interview, such was his fascination with it,” says David Gedge of the Wedding Present. “We would bare our souls to each other all the time. That was the nature of our relationship and I will sincerely miss that. We were honest with each other and listened to one another’s insecurities continually. He was very open with me; he’d quite often arrive at wherever we were meeting and launch into something incredibly personal. I once asked him how he was, and he said: ‘Well, my dad just died.’”

Hughes left Buzzcocks in 2002, and retreated from comedy, but he still pursued fame and wealth, albeit with less success. As well as the novels, he appeared as Peter Davison’s sidekick in four series of the gentle crime show The Last Detective, starred in the long-running West End play Art, and voiced the character of Finbar the Shark in the infants’ TV animation Rubbadubbers. I asked him why he took that role, given his desire to be treated seriously and his seeming lack of interest in kids. “Do you know how much money Neil Morrissey made out of Bob the Builder?” he replied.

“More than most, he was obsessed with money,” remembers one old friend. “I can barely remember him buying a drink. And that was when I was his best friend, and he had his own TV show. That’s the paradox: a man who was so jealous about money and also wanted to be an artist.”

Perhaps he realised that being a comedian was what he was best at. He returned to standup in 2006, building up to the show about the death of his father – Life Becomes Noises – that seemed to mark a decisive return as a solo stage performer.

“Maybe he got back to doing it on his own terms,” says the comedian Adam Hills, who became close to him in recent years. Hills mentions a remark Steve Martin once made about being a superstar comedian, that if you do new material the audience don’t laugh because they want to hear the old stuff, but if you do the old stuff the audience don’t laugh because they already know it. Coming back, no longer a superstar, meant that Hughes could perform the comedy he wanted. “It felt to me in his last few years that he was doing it because he liked it.”

It seems he changed as a person, too. There is a stark divide between the memories of those who were friends with him at the peak of his fame and those who came to know him in recent years. They sound as if they are describing different people. Hannah Norris, an Australian actor who appeared with Hughes in his improv panel stageshow Blank Book says: “I knew of his reputation, but I never saw that man at all. He was very kind and very generous – and very gentle, actually. Maybe that was something that had changed.”

And how was his attitude to Norris, not as an actor but a woman? “I hung on to the idea of having a woman’s voice in Blank Book. Being on stage with three men, I tried to include a woman’s voice, and he valued that. He said that to me. He said he liked hearing that.” Donnelly agrees that his attitude towards women changed, that his anger and cruelty had dissipated, perhaps because “in the last five years I would say he had no interest in sex any more”.

Hills first met Hughes 20 years ago, as his support on an Australian tour, but their friendship developed in recent times. Like Norris, he never experienced the man who could be so vindictive. “What I felt in the last couple of years was how genuinely concerned he was about how I was doing and how much he cared.”

Donnelly, too, was helped and nurtured by Sean: they became friends when he was asked to support him on a tour of Switzerland, which he remembers as being “like a holiday”. He would see flashes of the old Sean, “but I’d always try to be the voice of reason. We bonded over lots of stuff; we’d go and mooch around Tate Modern. He taught me more about art than anyone I’ve ever known. He’d talk about art like he talked about football.”

The last time I saw Sean, he was not drinking. It was peculiar, spending an evening alone in a pub with him, just a mineral water in front of him. My main memories are of large groups of people and large amounts of alcohol: one peculiar night getting very drunk with “some friends” who turned out to be most of the cast of EastEnders; the night a group of us were doing a pub quiz and Gem Archer, newly installed in Oasis, walked in – everyone turned around to stare, and Hughes observed, loudly: “He’s in here all the fucking time but until now he’s just been that cunt from Heavy Stereo.” As was often the way with Sean, it was a joke, but it felt as though it was delivered with teeth.

But then he returned to drinking, telling the Irish Times: “Apparently I’m tedious when sober. People were uncomfortable when I wasn’t drinking. It made them question their own habits.”

“That was bollocks,” Donnelly says. “When he wasn’t drinking he was the most stable I ever saw him, but he flat-out told me he was bored. He didn’t have much in the diary – he only did short tours – and he just told me he was bored. So first he started smoking again, absolutely chaining it. And then the drinking started again … When he first gave up, he just stopped overnight. So I always thought it wasn’t an addiction in that full-on sense. But in the last year, since his mum died, it spiralled. It was horrible. I’d speak to him at 10am and he’d be pissed.”

Yet Hughes was able to compartmentalise his life so thoroughly that other friends had no idea what was happening. “It didn’t seem to me that he was drinking a lot,” Hills says. “It’s been very disconcerting the last couple of days, because the Sean I knew had been in good health and good spirits.”

I always wondered if he had been lonely. “I think he was a lonely person,” Donnelly says. “And he found it hard to hold down relationships. He would call friends claiming he needed to check something, but really he wanted someone to talk to.”

Mark Lamarr is the comedian with whom Sean’s name is perhaps most closely associated, thanks to his hosting of Never Mind the Buzzcocks. “I guess you could have called us both womanisers,” he says. “We were both young, rich and famous. We both had lots of girlfriends. One day he rang me, and it was the only time I remember him reaching out with sadness. He said: ‘I really worry you and I are going to end up being lonely old men. I said: ‘I’m not worried, because I like being alone.’ The big sadness is that he didn’t even get to be old. He just got to be lonely.”

It’s hard to write about Hughes, not just because he had been my friend, but also because my memories – like many other people’s – are not all positive. I can laugh about the time at a Cure aftershow party when he tried to convince people he was the estranged nephew of far-right Austrian politician Jörg Haider, but I can also recall his unerring eye for other people’s weakness and insecurity, and his willingness to deploy it. I can smile at the memory of going with him to watch Crystal Palace, and him shouting at the Charlton player Luke Young, in his best Obi-Wan Kenobi voice, “Run, Luke, run!” every time Young was in earshot, but then I think of women I know who had encounters with him and how horrified they were by his behaviour.

I shall go to his funeral on Monday, and I will still be asking myself: who was my old friend? And why did his life turn out this way?

This article was amended on 19 October 2017 and 11 January 2019. An earlier version said Luke Young was a Crystal Palace player. This has been corrected to say he played for Charlton. The surname of the actor Hannah Norris, having been mistakenly published as Morris, has been corrected.

Note added 27 July 2018:

This article generated complaints about its contents and timing. The role of the readers’ editor is to consider complaints under the editorial standards and make independent decisions. Guardian editorial guidelines, like most journalism codes, require that people be treated with sensitivity during periods of grief and trauma.

The relevant editors told me they were sorry that the article had caused distress, which had not been intended. The article included tributes to, and warm memories of, Sean Hughes, but to build an honest portrait, the editors said, the story had to include his complexities. Asked specifically about the timing of publication, the editors said that “the aim was to contribute to the understanding of a well-known figure at a time when the public was actively engaged in trying to understand what had happened in his life in his later years.”

I concluded that in this case the Guardian in some respects met its standards and in others did not.

When a very well known and popular figure dies, the family and friends’ grief is, in a sense, shared by the person’s fans. It is legitimate for journalism to recognise and try to address this broader and more distant type of loss, though it needs to be done with sensitivity when grief is fresh.

Sean Hughes died 16 October 2017, the article was published 19 October, the funeral was held 23 October.

Overall, the article is well-rounded and within the editorial standards. It covers the talent, innovation, success, popularity and breadth of interests of Sean Hughes. It pays attention to his generosity towards others, his love of fine art and of music, and his ventures into poetry, novel-writing and acting. It is also critical - of his drinking, arrogance, capacity to be close-then-distant in relationships, ambivalence about his own fame, and his ability to recognise and play on a person’s insecurities. The article bluntly says that sometimes he could be cruel.

One paragraph refers to people having had bad experiences with Sean Hughes, especially women.

In fairness to the author of the article, I note that the final form of that paragraph and its publication were results of decisions made, not by the author alone, but in the editing process.

I concluded that the paragraph was misjudged, not because it mentioned women having had bad experiences with Sean Hughes, but because, having raised the matter, it did not specify those experiences and, insofar as possible, attribute them to one or more accusers.

This should have been done because, to raise the issue about a man who is no longer able to respond requires sufficient specificity for the allegation to be assessed and for readers to be able to form a view for themselves. Details were necessary because of the significance of raising the issue during a period in which society was absorbing the #MeToo moment, in which some of the known serious offenders have been men in show business. The juxtaposition with an assertion of cruelty made it all the more important not simply to float such an allegation, but to ground it in stated facts.

The distress that floating such an allegation without detailing it would be likely to cause Sean Hughes’ family and friends, so soon after his death, was foreseeable and ought to have been given greater weight by the decision-makers.

- Paul Chadwick, Guardian readers’ editor