A federally funded museum is telling Americans not to think. On June 24, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum instructed the public not to consider the relationship between its subject, other historical events, and the present, implicitly reprimanding Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez for calling American detention centers “concentration camps.” In doing so, it has made nonsense of the slogan “never again” and provided moral cover for ongoing and oppressive American policies.

The Holocaust matters to Americans as the source of moral lessons. The choice we face is whether the lesson is that we are always right or whether the lesson is that we should judge ourselves critically in light of the past. At first glance, the museum’s rejection of “analogies between the Holocaust and other events” might seem like a laudable attempt to affirm the unprecedented character of the mass murder of the Jews of Europe. In fact, it makes conveying the weight of that atrocity impossible, and it releases us from any obligation, as a nation, to self-criticism.

Analogizing is not some mysterious operation: It is how we think. Every time someone asks you for advice about a situation beyond your personal experience, or every time you are faced with an unfamiliar choice, your mind makes analogies with what you do know. Then you ask questions that allow you to clarify similarities and differences. At some point, you have understood and can act. “Never again” is nothing other than an invocation of that process. We start from what we know about the present and make our way back to the 1930s and 1940s. Once we understand something about the history of the Holocaust, we make our way forward again, seeing patterns we would have missed. If we notice a dangerous one, we should act. Without this effort, though, “never again” becomes its own opposite: “It can’t happen here.”

A basic pedagogical device is to ask someone to imagine him or herself in another position—say, as a Jewish child in hiding in Amsterdam. That is a historical analogy, invoked millions of times, one that some teacher or museum guide has used somewhere today. To forbid analogies makes the Holocaust irrelevant to future generations. If an American child can identify with Anne Frank, an American child might ask what it is like for immigrant children to be separated from their parents. To forbid analogies is to forbid learning, and to forbid empathizing. That, sadly, is the point.

The cost of the museum’s new policy is our intellectual and moral heritage. Some of the great thinkers of the past century were Holocaust survivors who asked what the Holocaust meant for history and for the present. If we reject analogies, we trash the poetry of Paul Celan, the philosophy of Hannah Arendt, the ethics of Emmanuel Levinas, the diaries of Victor Klemperer, and the novels of Vasily Grossman. It was Grossman, reporting on the death factory as a journalist in the Red Army, who gave us the crucial account of Treblinka. Is he to be blacklisted for also leaving us a moving recollection of Stalinist famine in Ukraine, and comparing the two?

It is not just the elevated thought of these and other Jewish survivors that arises from historical analogies involving the Holocaust. For better and for worse, American politics also depends on them. American movements for social justice and civil rights included Jews who thought they could apply the lessons of the Holocaust to America, and black Americans who saw in the Holocaust an example of the politics of empire. The Cold War was fought on the basis of an analogy: The United States should not appease Stalin as the Europeans appeased Hitler. The second Iraq war was fought on the same analogy.

Analogies, instructive or deceptive, are all around us. Analogies in conversation with one another, subject to modification by evidence, can instruct. But a monopoly on historical interpretation, claimed by a single institution, is a mark of authoritarianism. This is where the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and other enforcers of taboo are taking us. It is where a democracy must not go.

The point here is not that we all have to agree with Ocasio-Cortez’s declaration that “the U.S. is running concentration camps on our southern border.” The point of historical comparisons is not to seek a perfect match—which can never be found—but to learn how to look out for warning signs.

How many people, after all, know that a major act of violence carried out by the Nazi SS was the deportation of Jews deemed to be illegal immigrants? To note this fact at the present moment is to suggest an analogy. Or, rather, the analogy suggests itself, once you know the fact. That is one of the dangers of placing a taboo on analogies: It ensures that we never learn what we need to know.

American policy now is to apply violence to people who lack American citizenship. We subject undocumented migrants to procedures forbidden by international law, such as detention itself, and deny them rights guaranteed by our own Constitution, such as due process of law. These abuses command attention in and of themselves. In historical terms, the worrying thing is that separation from state protection can be the first step toward something much worse. We rightly think of the Holocaust as the attempt to remove Jews from the planet by murdering them all. In its unfolding, however, an important early step was the stigmatization and deportation of Jews who were not German citizens.

On the night of Oct. 28, 1938, the SS rounded up about 17,000 Jews who had Polish citizenship and forced them across the Polish border. Often these were people whose whole lives were in Germany, including children who saw themselves as Germans. Consider the Grynszpan family. Their teenage son, Herschel, was in Paris when his parents and sister were deported. On Nov. 3, he received a postcard from his sister: “Everything is finished for us.” Soon after, Herschel shot and killed a German diplomat. In Berlin, Goebbels used this as a pretext to organize Kristallnacht. It does seem worth asking just how far away we are from a scenario where stigmatization, family separation, and deportation lead to some similar escalation.

The Holocaust could only proceed when state protection was stripped from Jews. The experience of murdered Jews has more to do with statelessness than it does with concentration camps. Roughly half of the Jews murdered in the Holocaust were shot over pits close to their homes. These people had almost never seen a concentration camp. But some of their murderers had, as guards. A concentration camp is a lawless zone, and the SS was an institution that existed beyond the law, in a murkier world defined by Nazi racial ideology. Mass murder was possible when a lawless institution operated in the vast, lawless colony the Germans created in Eastern Europe. The extreme case suggests a general lesson: The rule of law should prevail everywhere, and states of exception should be kept to an absolute minimum.

In late 1941, Germans developed a new method of industrial murder: forced exposure to automobile exhaust. Rather than being shot to death like Soviet Jews, Polish Jews would be asphyxiated. At Bełżec, Sobibór, and Treblinka, the stateless Jews of Poland, enclosed in ghettos for a deportation that never happened, were instead dispatched to killing centers. In the summer of 1942, the SS leadership concluded that the food consumed by the Jews working in the Warsaw ghetto was more valuable than the forced labor they were performing. Famished Jews were lured to the transport site by the promise of bread and marmalade.

Yes, the Holocaust had marmalade—in the exhausted minds of tormented Jews. Working bit by bit, you can perhaps understand this history from the perspective of the victims, because you too can imagine the marmalade. You know something about work and something about hunger. You can ask what it would be like to be very hungry after more than a year of forced labor. You can empathize with Bluma Bergman as she recalls that starving Jews in the Warsaw ghetto in 1942 would do anything for a bit of food, “even if you know that you’re going to be killed.” Knowing what it is like to fancy a roll with jam, you can try to conjure at least one of the horrible details of this most horrible history. But you can only do so with analogy, factuality, and empathy.

If you do not think, you will not see where you might go wrong. Last year in my home state of Ohio, ICE used doughnuts to lure hungry migrants to a place where they could be arrested, seizing mothers and leaving children behind. While that is not exactly like using marmalade to lure Jews to the Umschlagplatz, it is not a gambit of which we can be proud. The same kind of mind drew suffering people with sugar in 2018 as in 1942. We can insist on the differences all day, but at the end of the day, we should be ashamed.

The main instruments used to kill Jews were guns and internal combustion engines. Thinking about these tools of death is another way to start thinking back. You might have handled a gun, so you can think about what it means to use one against children. You have probably pushed down a gas pedal and expelled noxious fumes into the air. You can imagine what happens when exhaust is pumped into a closed chamber that holds human beings.

With the physical tools in mind, you might ask: What would people like me go through before becoming killers, before using those familiar objects in unfamiliar ways? Or, more modestly, in what conditions would I or my compatriots do things that, in normal life, would be deemed unacceptable? It is here that we should ask where working in legally gray places like our detention centers leads. They are not the entirely lawless zones of the concentration camps, but they have routinized obvious abuses of human rights and are demoralizing some of our fellow Americans, or at least putting them into situations where their worst impulses can thrive. Some of these men, for instance, seem to think that our elected representatives should be raped. Apart from anything else, this is an early sign of how lawless action within a confined zone encourages lawlessness as a way of seeing the world.

Thinking your way back does not make you a perpetrator any more than it makes you a victim. Our preference is to see ourselves as victims, and thus, if anyone seems to be referring to the Holocaust and to us, we reflexively defend our innocence. That is what is happening now: One of our official institutions of memory is defending our innocence, treating us as the offended victims.

But the moral lesson of the Holocaust is not that you risk being a victim. The moral lesson of the Holocaust is the danger that you will ignore the victims. Or torment them. Or worse.

The taboo on analogy is often presented as respect for the survivors. This is how Rep. Liz Cheney, for instance, framed her shaming of Ocasio-Cortez. But using survivors this way silences their voices just as we are beginning to hear them. When West Germany debated the legacy of the Holocaust in the late 1980s, the prevailing view was that Jewish voices could only add emotion. What we have found since, as the use of testimonies became the norm in the 1990s and as records from Eastern Europe have become available, is that Jewish voices add factuality, perspective, and thought.

To reject historical analogies is to disqualify the recollections of the people most directly concerned, the Jews themselves. We may think now that we know what the Holocaust was, but survivors could only communicate in terms they inherited from the past. Some Soviet Jews spoke of Stalinist terror. Polish Jews recalled pogroms. Rabbis reminded their congregations of biblical suffering. In 1941 and 1942, Jews in the occupied Soviet Union associated public shootings with Yom Kippur. All of these are imperfect analogies, because all analogies are imperfect. Yet such attempts to make sense of the unfamiliar generated a language of experience that allowed Jews to describe the Holocaust. After the war, survivors continued (and continue) to use historical analogies. One survivor might understand the genocide in Cambodia from her own experiences, or ask whether we have learned enough from the Holocaust. Other survivors would draw different lessons, such as that of Zionism. The French historian Jules Michelet said that the nation is a daily plebiscite. Israel is a daily analogy.

We need analogies to apprehend facts and experience empathy. But we also need them for conceptual thinking, including about the Holocaust itself. The concepts we use today grew from historical analogies. The term ethnic cleansing was created by Serbian perpetrators to describe their own practices in the early 1990s; we now use it to describe similar actions before and after. The term genocide was created after the Holocaust by the Jewish survivor Raphael Lemkin, in a body of work that is full of historical analogies and comparisons, to describe attempts to destroy a culture by violence or other means. The Hebrew word Shoah, which came into widespread use after the 1985 documentary by Claude Lanzmann, works by analogy: It is “the disaster that comes from afar” with which God threatens the Jews in Isaiah 10:3.

The same holds for the word Holocaust. Like many terms we take for granted in the present, it arose from a series of encounters with the past. The ancient Greek term from which Holocaust arose meant a burnt offering; then, in early modern Europe, a holocaust was the death of humans by fire; then, by the 19th century, it came to mean a cataclysm generally; then, by the late 20th, the mass murder of the European Jews.

One of the reasons the word has such particular force in American English is that during the Cold War, before the Jewish Holocaust became a central element of American memory, we used Holocaust in the sense of “nuclear holocaust.” We shifted from one to the other almost seamlessly, preserving the sense of “the worst thing imaginable.”

Placing a taboo on discussions of concentration camps is even more grotesque than placing a taboo on discussions of the Holocaust, since it moves the veil beyond wartime Europe and allows it to fall over the whole history of the modern world. Rejecting all references to concentration camps would mean forgetting European imperialism, the Soviet Union, and contemporary China. Incidentally, no one seemed to mind much when Anne Applebaum, a distinguished historian of communism, thoughtfully applied the phrase “never again” to China. Chinese human rights abuses are on an entirely different scale than American ones, and Applebaum is right that they deserve more attention. But it is illogical to apply historical terms to others while insisting on a safe space for ourselves.

The more reference points we have, the more complete our picture of risk. The detention centers are like concentration camps in some respects: They are hidden from sight and subject to a minimal regime of law. They are unlike concentration camps (at least in the German and Soviet conception) in that their initial purpose is not to isolate some citizens from others for fixed durations in territorially defined lawless zones. Historians of empire, who have a broader view, might disagree with me, and they might be right—just as Ocasio-Cortez might be right.

Our detention facilities also recall ghettos in some ways: They physically separate the people with the least state protection from others, they concern whole families (often with members separated), and they depend on a society willing to denounce neighbors. German concentration camps were used at their inception to punish people for their political views and then for their social behaviors, and were only later (after that first Jewish deportation of 1938 and Kristallnacht) used to punish a group defined by origin. The same pattern roughly holds for Soviet concentration camps.

Our detention facilities were ethnic from the outset, and are seen by the public in that way, and in that sense more resemble ghettos. Like the ghettos, our detention centers create unhealthy opportunities for profit by private companies. Unlike the ghettos of Nazi Europe, they do not serve the horrifying vision of the physical elimination of an entire society. They do, however, serve a politics of us and them in which we are the good and lawful ones and they are the evil and lawless ones.

Perhaps the most Orwellian aspect of the museum’s position is that it attempts to ban a healthy mental operation that the human mind reflexively performs: learning. No analogy with the 1930s or 1940s will be the perfect fit—if it were, it would not be an analogy!— but so long as we are all working together in good faith, the range of our knowledge and empathy expands, and the mental effort necessary to learn from the past can serve to create a better future. The more we learn about the Holocaust, the more we understand it as an unprecedented horror. The broader our knowledge of that unprecedented horror, the clearer is our insight into present challenges, and the better our chances of avoided future disasters. The problems begin when we take the past to mean that we are always innocent—that past horror demonstrates our present righteousness and, therefore, that whatever we are doing now is justified.

One obligation, when we say “never again,” is to ask what Americans did the last time around. When we use the memory of the Holocaust to flatter our own moral character, we take for granted that we did the right thing in the 1930s. This is not the case. We initiated diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union in late 1932, just as Stalin plunged Ukraine into famine. Hitler praised our immigration policies and our Jim Crow laws. Much American reporting on Hitler was quite admiring. Some advocates of “America First,” such as Charles Lindbergh, wanted an alliance with the Nazis to protect white people from everyone else. Jews in the United States hesitated to speak of the oppression of Jews in Europe, fearing that an anti-Semitic backlash would make it less likely that the United States would enter the war.

The United States did go to war, but not to save the Jews. The Holocaust was largely over by D-Day. American soldiers liberated horrifying camps, such as Mauthausen, but never saw the death factories or the death pits. As Elie Wiesel’s presidential commission recalled when it recommended the creation of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the basic reality was “the absence of American response” at a time emigration might have saved millions.

In the public discussions of the late 1930s, there was little concern with the specific plight of Jews. One American congressman boasted that “I have been able to prevent the throwing open of the country to the scum and refugee” by halting an “invasion of foreigners.” Others rejected a proposal to take a fixed number of Jewish child refugees from Germany on the logic of putting “America and Americans first.” Whatever “never again” means, it cannot mean using the same words now as we did then.

“Never again” means accepting that history might make us uncomfortable. Because analogies are indispensable, an attempt to ban them really means something quite different, a defense of complacency when criticism is needed. When historical comparison is suppressed, we no longer have political thought: We have political taboo. We no longer have civil society: We have authoritarian conformity.

Liz Cheney indignantly used the murdered Jews of the 1940s as a rhetorical shield for American human rights abuses now. In its statement rejecting analogies, the museum used the murdered Jews of the 1940s as a rhetorical shield to defend Cheney’s unreasonable position. In reality, the museum was not resisting all historical analogies. It was silently endorsing our official American one: the one that says that since we were the good guys then, we are the good guys now and forever, regardless of what we do. The museum’s position opposes all other analogies, which means the ones that might help us empathize and consider and act. That is defending the status quo—no matter how bad it becomes.

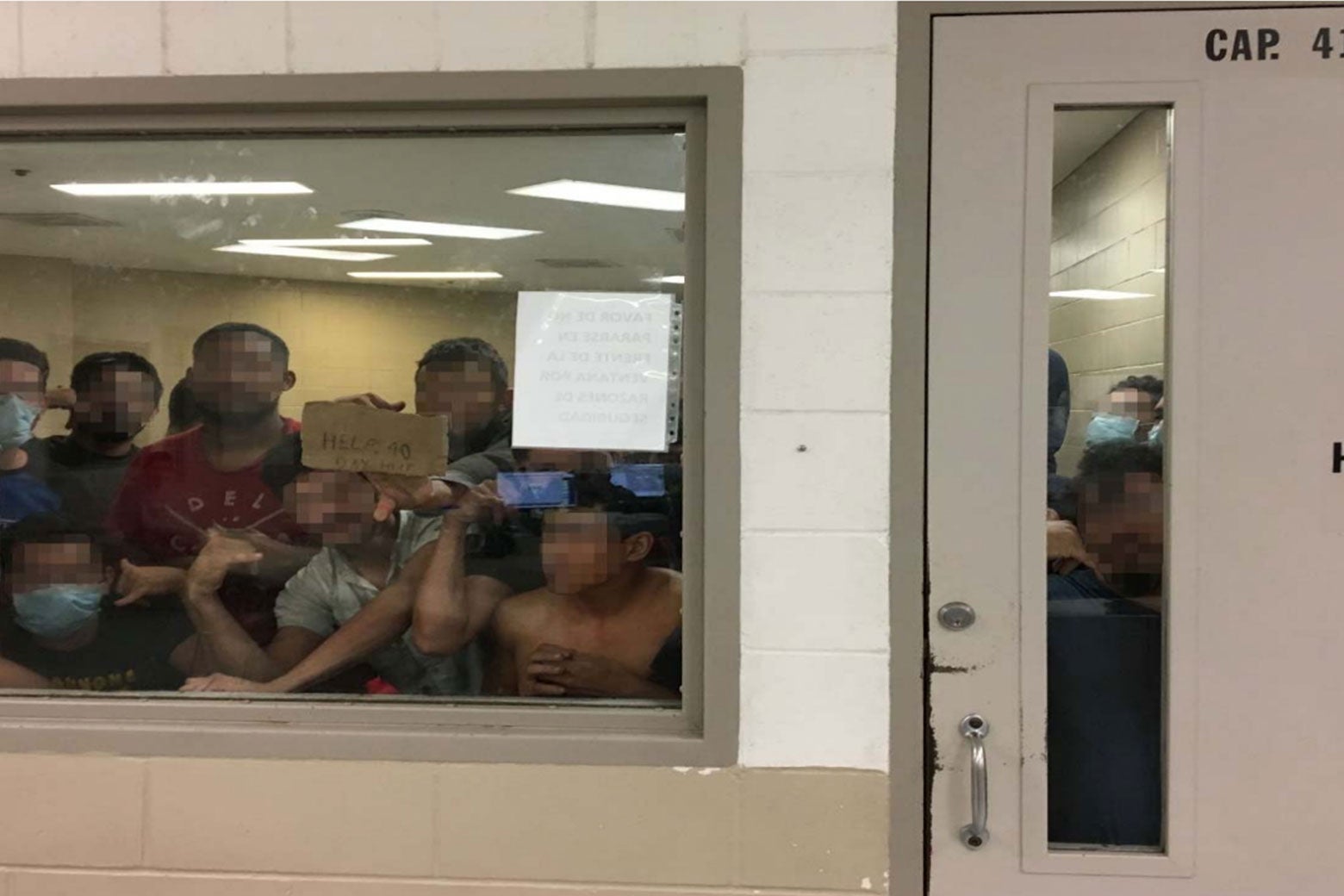

And just what is the status quo? What are we Americans doing now, in 2019, at the border and in our detention centers and our towns? Despite valuable accounts from lawyers and doctors, citizens in general do not seem to know—just as no one seemed to have a very clear picture of the camps or the ghettos of the 1930s and 1940s. In a free country, we would all be able to visit the detention facilities we pay for with our tax money. It is a bad sign for our democracy that we cannot. Journalists are barred from such facilities, and even members of Congress must give two weeks notice. Just what conditions require such restrictions on access? We should find out now, rather than be asked by our children and grandchildren later.

In the meantime, let the museum retract its statement so that we can all think together, within the past that we share and the future we have to build together. This may seem like a small thing: one statement from one institution. But words matter, and words about the Holocaust from a guardian of its history matter especially. Words can shield us from a sense of responsibility when crimes are committed in our name. The museum is using words to transform yesterday’s crime into today’s excuse, thereby preparing the way for tomorrow’s horror. That the next atrocity will be different than the last one is not a reason to let it happen. It will be ours, and we have been warned.