No one saw it coming, the wave of television crews, camera lights, and reporters that crashed onto an outdoor sports arena in a small town in Mexico’s Oaxaca state.

I certainly didn’t. And neither did the hundreds of exhausted migrants camped out on blankets and inside empty buildings in the town of Matías Romero. Or the volunteers with Pueblo Sin Fronteras tasked with guiding a caravan of up to 1,500 people who’d formed the largest Central American group ever to have departed the Mexico–Guatemala border headed toward the United States. Or even the reporters and photographers who hadn't covered the caravan's initial days because they didn't realize that this one's size made it different from the ones that had come before it, annually.

But a series of tweets from President Donald Trump changed that, thrusting this group of Central Americans into the unforgiving glare of the international spotlight and upending what had been the usually unseen journey of people fleeing to the United States.

Gina Garibo, a fast-talking political science professor at the Ibero-American University in the Mexican city of Puebla and a volunteer organizer for Pueblo Sin Fronteras, stood on the grass of the sports arena and watched as camera crews set up tripods and reporters rushed to get quotes from the Central Americans sitting next to a soccer field. A drone flew over the crowd. The glow of camera lights would be a constant in their lives for the weeks that followed.

It was a lesson in the consequences, in the age of Trump, of getting the attention you thought you wanted.

"It was too much — this was more media attention than we ever expected," Garibo told me. "That's when we realized that the media is like a double-edged sword."

People all over the world knew about the caravan and the migrants propelling it forward, all with variations of the same tragic tale — forced from their homes by gangs, of loved ones threatened or raped or murdered.

But now they were also facing the wrath of Trump’s tweets, and soon they would feel the crushing weight of the US and Mexican governments, as the caravan became the center of a political game and a media storm, even as the migrants grappled with what it meant to suddenly become the face of their fleeing compatriots.

It was a lesson in the consequences, in the age of Trump, of getting the attention you thought you wanted.

Pueblo Sin Fronteras had been trying to draw media attention to migration issues for years.

The group doesn’t care much for borders, as its name suggests, translating directly to "People Without Borders," though not to be confused with a DC-based nonprofit of the same name. They call themselves a “collective of friends” who decided to be in “permanent solidarity” with those displaced from their homes and draw on idealistic volunteers from all over the world.

Since 2010, the group has been running caravans of Central Americans across Mexico, spending hours in the weeks leading up to a caravan on conference calls because it’s a transnational effort, dividing up work, setting scheduled stops (though logistical decisions are often made on the fly), and preparing statements. The organizers were people who in their day-to-day lives work with immigrants in the United States and Mexico. The volunteers are driven by various motives — empathy, personal stories, anger at an unjust system — but they're united by the desire to empower migrants and the belief that refugees have the right to a life free of persecution despite where they live.

“Our comrades are not charity cases — they’re fighters, they’re political people who have a right to live a life free of violence, a life of dignity,” said Garibo, who hails from the Mexican state of Guerrero. “At any moment what happened to them could happen to us, so it’s a shared fight, standing shoulder to shoulder and demanding justice shoulder to shoulder.”

“Our comrades are not charity cases — they’re fighters, they’re political people who have a right to live a life free of violence, a life of dignity.”

The caravans began as protest marches during Holy Week that compared the journey refugees must make with Jesus’s walk to his crucifixion. The early ones went only from Mexico’s southern border through the state of Oaxaca or never went past the towns they started at, because at the time the focus was less on getting people as far north as they needed to go and more on highlighting the assaults they endured along the way at the hands of criminals and authorities.

Since then, the volunteers have expanded their goals. They’ve mapped out safe routes for the caravans and established safe practices, training migrants in how to run security perimeters to keep from being victimized by gangs of thieves and worse. They teach people how to climb the freight train that has become known as “the Beast” because so many have fallen to their deaths or lost limbs when they fell asleep atop it or were pushed off by armed men. And they developed ways to help those seeking asylum in the United States by offering lessons on the vagaries of US immigration laws and the importance of documents such as birth certificates and marriage licenses.

Irineo Mujica, the head of Pueblo Sin Fronteras, started as a media-savvy activist who opened up migrant shelters in southern Mexico and a photojournalist documenting the plight of Central American migrants. A native of Mexico, he moved to the United States as a teenager and now holds dual US–Mexican citizenship.

For many years in the US, he felt disconnected from the immigrant community — until his father died in Arizona. Mujica felt that his father was often ignored and his wishes dismissed during the eight months he lay in a hospital bed because of his “indigenous” looks and inability to read or speak English well. For Mujica, that made the problems of immigrants personal, and the rage he felt after his father's death was softened by helping them.

"I wanted to bring people of privilege to walk, see, understand, and explain to others what happens."

After listening to the stories of migrant women being raped and people going missing in Mexico, Mujica went from doing community organizing in Minnesota to documenting the route the immigrants took. Then he started inviting reporters and others to travel with him on the freight train many Central Americans rode to travel north.

"I wanted to bring people of privilege to walk, see, understand, and explain to others what happens," Mujica said.

In 2008 he helped organize a Holy Week caravan. Tying the caravan to Holy Week and Jesus's walk to his crucifixion was a way to try to get Mexicans, who weren’t always kind to migrants, to empathize with their plight. "It was more brutal back then," Mujica said. "Migrants would be grabbed and beat up all the time."

Only 50 to 60 people participated in that caravan.

The caravan that set out this March was different. Not only did it include entire families, but it was much larger than any previous such undertaking, with 80% of the people composing it coming from Honduras. Rows upon rows of Central Americans carrying jugs of water, backpacks, and tired children took over entire lanes of highways in the beginning, confidently crossing immigration checkpoints. They marched past Mexican immigration agents who, under different circumstances, might have made a move to detain them, since they were in Mexico without legal authorization.

Still, they never knew how authorities would react, something Mujica told the group on the second day as the caravan encountered an immigration checkpoint in an area called "la Rosera," a few miles outside Huixtla, Chiapas. Normally, migrants take back roads to avoid the checkpoint and often fall prey to criminals who lie in wait. Their fear of being sexually assaulted or robbed by criminals was in addition to worrying about being detained — or worse — by immigration agents. Mujica had prepared them for the hazards that experience had told him the group might expect.

"This is the most dangerous checkpoint," he yelled. "Its walls are covered with the blood of migrants... There's a tree behind it where a lot of people were raped."

But this mass of people made assaults by criminals or the possibility of being stopped by authorities unlikely; it was simply too big. The group marched unchallenged through the checkpoint, avoiding the back roads. Then it marched right past a military base and federal police vehicles. No one made any effort to challenge them.

There was no doubt that the sheer size of the caravan made the trek safer because they were able to walk in the open — as news reports proved during the month the group made its way north. Elsewhere, 136 Central Americans, 49 of them kids, were found alive inside a sweltering truck without food or water in Veracruz. Twenty-five others were hidden inside a freight truck that flipped over in Mexico’s northern Nuevo León state, leaving five seriously injured. Another 55 migrants were discovered packed into a cargo truck discovered by federal police during an X-ray scan. A pregnant 23-year-old died after the freight train she was trying to board cut off one of her legs.

"Who can stop us?" "Only God!"

Five days into the trek, by the time they reached their third checkpoint, some caravan members had grown emboldened, staring three Mexican agents defiantly in the eye, punching the air with their fists, and shouting “Si se pudo,” which roughly translates to “It can be done.”

“Who can stop us?” one migrant, named Dennis, yelled into a megaphone as they marched on.

“Only God!” the group screamed.

Under a different administration, the caravan might have gone unchallenged, unnoticed, or ignored.

But Trump has made a habit of issuing threats and trying to dictate policy through his Twitter account, and, after seeing a segment on Fox & Friends, based on a BuzzFeed News report on the caravan, he did not hold back, tweeting: “Border Patrol Agents are not allowed to properly do their job at the Border because of ridiculous liberal (Democrat) laws like Catch & Release. Getting more dangerous. ‘Caravans’ coming.” In the next few days he would tell Mexico they had to stop the caravan and would order the National Guard to the southwest border.

The organizers’ phones began ringing nonstop. “No, the caravan is not disbanding,” Garibo would say into her phone. “Yes, the migrants have a right to ask for asylum.” The moment she hung up, another call would come in. It lasted for days. Reporters on the ground would constantly tap her on the shoulder as she walked through the compound. If she did 20 interviews in a day, it was nothing.

From one day to the next, not only did organizers have to figure out a way to push forward with the largest group of people they had ever had, but now they had to do it while the world watched and Trump put pressure on the Mexican government to stop them.

Mexico has the absolute power not to let these large “Caravans” of people enter their country. They must stop them at their Northern Border, which they can do because their border laws work, not allow them to pass through into our country, which has no effective border laws.....

“The caravan, the pressure of stopping, it is a possibility. Whether there’s pressure or not, this number of people for us is problematic,” Mujica told me moments after Trump tweeted, setting off a firestorm that would captivate the country for weeks. “If there’s pressure to stop it, we do this every year and migrants are going to keep coming. I don’t know what to tell you. Let him put pressure. Let him.”

In the wake of Trump’s statements, the Mexican government dispatched a delegate from its National Migration Institute to defuse the situation. He was direct in his talks with the Pueblo Sin Fronteras representatives: The Mexican government was under a lot of pressure to break up the caravan. The caravan was too big, too visible, and there were too many women and kids. It wanted the caravan disbanded at Mexico City, a two-hour drive away.

Pueblo Sin Fronteras officials were equally adamant: They’d pledged to make it to the border.

Among the hopeful asylum-seekers they were taking with them was a 52-year-old woman named R. Rodriguez and her two grandsons. She asked to be identified only by her last name and first initial out of fear of damaging her asylum case and drawing retaliation from gangs back home. While the caravan organizers and the government tried to come up with an agreement on the best way forward, Rodriguez was more concerned with making sure her grandsons, whom she raised and who call her mom, had enough to eat. She was running short on funds and was relying solely on the food that locals donated as the caravan made its way through towns across Mexico.

She was worried about her 7-year-old grandson, skinny as a rail, who was refusing to eat after catching a stomach bug. And she had lost her cellphone after her 11-year-old grandson left it unattended, and it was stolen. There was now no way to contact concerned family members back home.

Before joining the caravan, Rodriguez had spent more than a year stuck on the Mexico–Guatemala border, renting a small apartment and working odd jobs in Tapachula. The border town is a crossing point into Mexico for asylum-seekers from all over the world and has developed a reputation as a prison for those who are too poor to continue north, spending their lives hiding from Mexican immigration agents and facing long waits to hear if Mexican authorities have granted their asylum requests. That’s become especially true in recent years as Mexico came under US pressure to crack down on Central Americans, who flooded the US border with children during Barack Obama’s second term. In 2014, with US prodding and US funding, Mexico created what is known as the Southern Border Program to stop Central Americans and send them home. In that program’s first year, Mexico doubled the number of people it caught and deported.

Rodriguez’s story was typical of people fleeing Central America. In 2017 she escaped El Salvador, a country roughly the size of Massachusetts that has one of the highest homicide rates in the world, with 60 killings for every 100,000 residents, according to a report from Igarapé Institute, a nonpartisan Brazil-based think tank. (The US rate is four per 100,000 people.) The killings are disproportionately committed by gang members, or "las maras" as they are known in Central America, with roots in the US. Trump has focused increasing ire on MS-13, a gang that was born in Los Angeles by people forced to flee El Salvador due to violence funded by the United States in the 1980s. The same criminal organization's violent tactics are now forcing a new generation to leave Central America by the thousands.

In El Salvador, nine years ago, members of the local MS-13 gang tried to persuade Rodriguez’s son-in-law to extort her. He refused, and they killed him. "We found his body — he was beaten to death," Rodriguez said. "My daughter fled to Panama, and I told her to leave her son with me. He was 3 years old at the time."

Despite the killing of her son-in-law, which terrified her, Rodriguez stayed and continued to run her bakery and raise her two other daughters — beautiful girls, she said, which in a country plagued by gang members can be a curse. A gang member kept asking her then–16-year-old daughter to be his girlfriend, which is often akin to being a sex slave. Rodriguez asked him to at least let her finish school, but her worst fears were soon made real when she got a call from a man who said he had kidnapped her daughter.

"You didn't want to do it the easy way," Rodriguez recalled the gang member saying. "Now we'll have to do it the hard way." He demanded $7,000 for her freedom and warned Rodriguez that if she called the police, they would kill her entire family.

"They've taken everything away from me," Rodriguez said of the gangs. "There is no hope left in my country."

When the gang called her back two hours later, Rodriguez had to tell them she still didn't have the ransom money. The man on the phone replied: “Hey, we’re going to rape your daughter now. And there’s seven of us," the voice on the phone said.

With the help of neighbors, Rodriguez put together $6,400 of the $7,000 demand and collected her daughter on a quiet street, her mouth gagged. Because Rodriguez didn’t have the full ransom, the gang members raped her daughter anyway. They then ordered Rodriguez and her family to "disappear" and not file a police report. Six months later, her daughter realized she was pregnant. A day after giving birth, she handed her son to Rodriguez and severed almost all ties with her mother.

Still, Rodriguez remained in El Salvador. The last straw came in January 2017, when gang members threatened to kill her and the two boys after she told them the oldest wouldn't collect extortion money for them. She left El Salvador on buses and crossed Guatemala with the vague idea that she might seek asylum in the United States, for herself and her grandchildren.

"They've taken everything away from me," Rodriguez said of the gangs. "There is no hope left in my country."

Hope had come in the shape of the caravan. It offered her not only protection along the entire route north, but also free legal advice from immigration attorneys who would be waiting for the group in Puebla, about a quarter of the way to the US border.

“I’m going to stick with the caravan for as far as it goes,” Rodriguez said one overcast morning. “I don’t know how I would’ve even made it this far, so I’m a bit nervous about what’s going to happen now.”

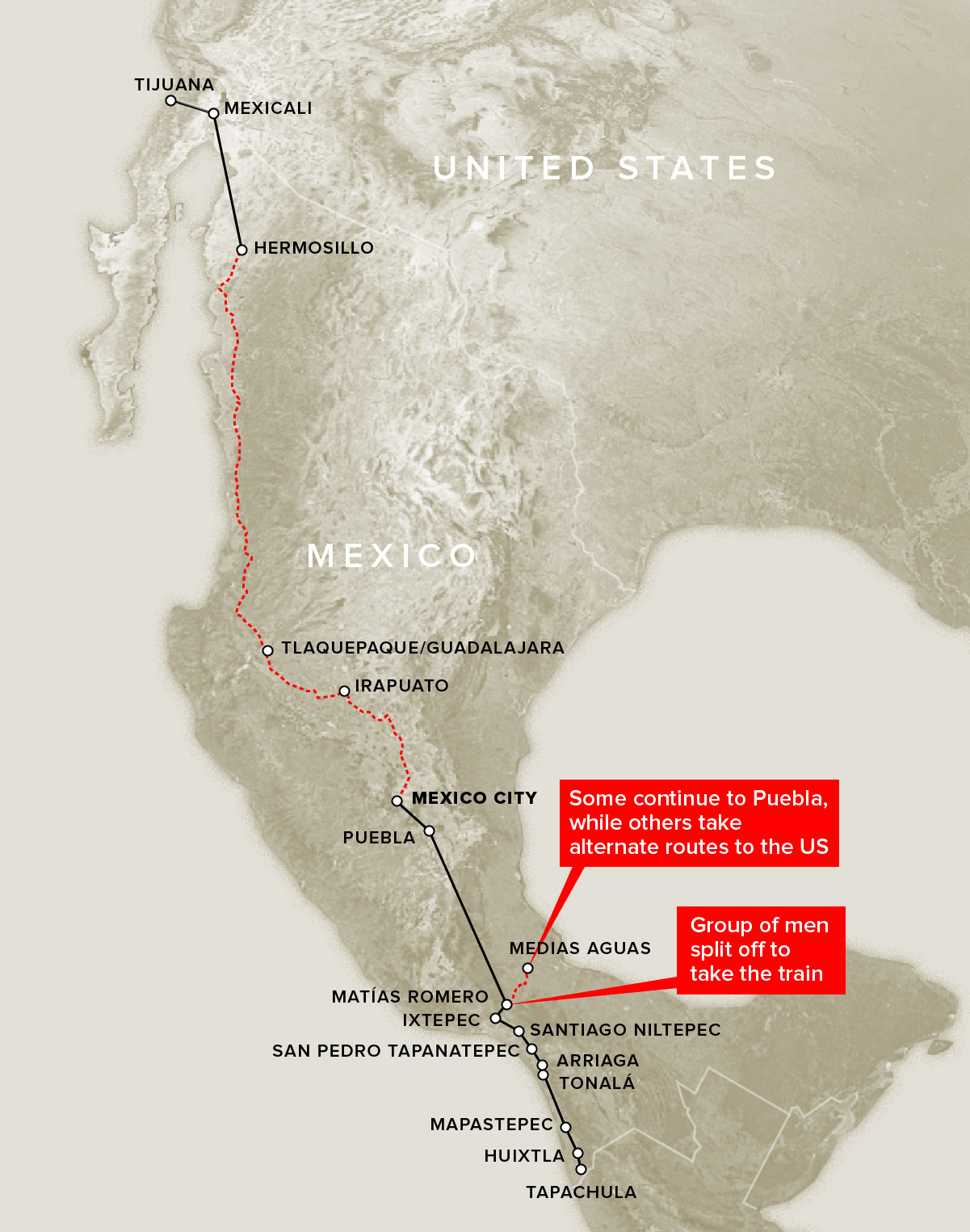

A group of around 300 migrants — mostly men, most ages 18 to 25 — had decided to separate from the group and ride “the Beast,” the train that has long been at the heart of the lore of Central American migration. Everyone was filled with apprehension and fear — they worried about armed cartels or assailants who could drag them off the train, not to mention the possibility of falling off its roof, as has happened to countless others before them. Anxiety kept them up through the night.

But once morning had risen and the train was ready to move, a calm descended on the group as we set off.

About two hours into the trip, I looked down at my phone and saw several texts. One of them, from my friend, read simply “Adolfo,” followed by a link to a Trump tweet.

Border Patrol Agents are not allowed to properly do their job at the Border because of ridiculous liberal (Democrat) laws like Catch & Release. Getting more dangerous. “Caravans” coming. Republicans must go to Nuclear Option to pass tough laws NOW. NO MORE DACA DEAL!

My stomach dropped. The president shot off the tweet following a Fox & Friends segment on the caravan based on my first dispatch from the field titled “A Huge Caravan of Central Americans Is Headed for the US, and No One In Mexico Dares to Stop Them.” The segment, on “an army of migrants” and the “reporter touting what they’re doing,” even used photos from my Twitter account.

“Now you're at the center of one of the biggest stories in the US,” my friend wrote.

The people on the caravan — 1,200 to 1,500 Central Americans — were a drop in the bucket compared to the more than 100,000 people arrested at the US southwest border in March and April alone. And only a portion of them were planning on going to the United States, with many having decided at the start of the journey or in the middle of it to try their luck in Mexico. Still, Trump had set his gaze on them and demanded that Mexico stop them — ignoring the fact that Mexico was already deporting more Guatemalans, Hondurans, and Salvadorans than even the United States — 80,353 people in 2017, compared to 67,544 by the United States, according to the Inter-American Dialogue, a US-based think tank.

“Now you're at the center of one of the biggest stories in the US.”

When we got off hours later in Medias Aguas, Veracruz, Mexican immigration agents were waiting next to white vans, but it was unclear what they'd been sent there to do. When asked, one of them told me: “My understanding is they will be left alone.”

Still, people on the caravan were worried. One man, a Honduran who’d lived in the United States under a program known as temporary protected status, told me the caravan was over. Mexican immigration agents, he said, had given them 48 hours to make it to wherever they needed to go. My mind quickly jumped to Rodriguez and the hundreds of women and kids waiting in Matías Romero who were relying on the caravan to get them to the border safely. Did they know that the caravan was over and that they would soon have to make the dangerous trek on their own, taking dangerous back roads filled with cartels that could kidnap or assault them?

The thought that I had made things harder for an already vulnerable group wrecked me. At the time, I didn’t see them as asylum-seekers or would-be undocumented immigrants or escapees of horrible places, but simply as people — hungry, thirsty, and tired by the side of the road in the midst of a huge journey that was already grueling enough.

I had done my job — reporting on a huge event, invited in by an NGO that hoped to educate the world about the plight of migrants through increased attention.

But the president’s tweet had changed everything instantly. In his view, the caravan was now an army of law-breaking migrants planning to storm the border to take over the United States, and something had to be done.

“On other occasions, we only had to worry about narcos,” Mujica would later tell me. “But to also have to worry about a president who wants to destroy and demonize us was difficult.”

Pueblo Sin Fronteras had organized the caravans to bring attention to the migrants and asylum-seekers — now they had it on a scale they never could have imagined, and they weren’t ready. The group’s philosophy is to never turn anyone away — and to empower the migrants themselves to help with the organization of the group, joining committees on everything from media to security. They never had more than 10 volunteer organizers on the ground in the early days — and sometimes the number was as low as five. For up to 1,500 people. They were overwhelmed.

The world’s media descended on the caravan, trying to figure out the true state of things in the face of Trump’s ever-escalating tweets and pronouncements. Many refugees gave interviews left and right — with little to no media training or information about how any coverage of their personal stories could affect their asylum cases later on.

Ultimately, the Mexican government said that instead of raiding the caravan it would offer to give its members transit permits good for 20 to 30 days that would, in theory, let people in the group travel freely throughout the country without having to worry about being detained by immigration agents. Mexican immigration ended up giving out 900 travel permits to members of the caravan over three days — something Pueblo Sin Fronteras saw as a nearly unprecedented victory in their push to allow migrants to move freely through Mexico.

The Mexican government’s motive wasn’t purely humanitarian — if its members felt comfortable going off on their own, the caravan, which had brought them such a headache, would be less visible.

Mexican officials had miscalculated, Garibo, the fast-talking professor, would later explain. They hadn’t taken into account that a lack of funds and knowledge would keep people from traveling off on their own, in addition to the fear that an immigration agent in the field would dismiss the permit document and arrest them. Instead of leaving on their own, hundreds decided to travel for about 11 hours on to Puebla, where the group would be divided between those with legitimate US asylum claims and those who would try their luck with Mexico’s immigration system. The city of Matías Romero would provide the buses to carry the 630 remaining members to their next destination.

“The caravan continues,” Garibo said.

Rodrigo Abeja, a Mexican volunteer with Pueblo Sin Fronteras, sat in silence in a taxi en route to the airport, his eyes drooping with fatigue. He had been with the caravan from the start; it was now nearing its end, and he had decided to fly home. He was satisfied, he said, but also broken.

"Every day was about survival, but we made it," Abeja said.

Abeja, who works as a community organizer with a coalition of groups that help migrants in the US and Mexico called the Popular Assembly of Migrant Families, was happy the caravan had made it to the border and fulfilled the promise Pueblo Sin Fronteras had made to the people. But Abeja said he didn't connect with the group as in previous years, and he missed that. As organizers, they were too busy trying to figure out a way to push forward with the largest group of people they had ever had while the world watched and Trump tweeted obstacles at them.

"Every day was about survival, but we made it."

Meanwhile, the caravan was reaching the US border, 32 days after it left Tapachula, on Mexico's southern border with Guatemala — the culmination of miles of walking, hitchhiking, and grueling train rides. In the end, 333 of those who had set out would cross into the United States to seek asylum.

Among them was Rodriguez, who was now well-versed in giving interviews to journalists — even becoming a member of the caravan’s media relations committee, helping to draft press releases. But she still blushed when she talked about it.

"Sometimes I feel like I'm just rambling," Rodriguez said. "Part of me felt happy to do the interviews because I felt like we weren't alone: The whole world knew about us and could see we're just looking for a better future for our kids."

She wasn’t the only one. Magdiel, a Honduran man seeking asylum after his father was tortured and killed, said: "Maybe sharing my story won’t help me or my family. ... My hope is that telling my story to the world will help my people who are still in Honduras."

For seven days, volunteers walked groups of refugees to the gray metal door that led to the United States so they could request asylum. The United States Citizenship and Immigration Services said 327 cases of people seeking asylum from the caravan were referred to them and 216 were screened. Of those, 205 passed their credible fear interview, successfully proving to an immigration officer that they have a legitimate fear of being returned to their country, a crucial early step in the asylum process.

What became of the rest of the 1,500 who’d started out is unclear. According to the Border Patrol, 122 people believed to have been part of the caravan were detained by agents trying to enter undetected into the United States. Around 100 more remained in Tijuana, uncertain what course of action they would pursue. Another 350 remained in Hermosillo, in Mexico’s Sonora state, seeking the humanitarian visas that Mexico had promised. The whereabouts of the other original members of the caravan are simply unknown.

Alex Mensing, 29, a paralegal at the University of San Francisco’s Immigration and Deportation Defense Law Clinic who serves as Pueblo Sin Fronteras' project director, said the group will probably do another caravan, though it might not look quite the same. One aspect they are evaluating is how to handle the media attention and how to make sure refugees don’t hurt their chances of asylum by sharing their stories.

"Some of us are a little more inclined to let the truth be seen and to allow asylum-seekers to determine what to say and when they say it," Mensing said. "Unfortunately, people are about to enter a legal process that will use everything it can to break them down and deny access to protection."

Mensing, whose journey into the immigrant rights movement started in high school when he studied in Argentina and continued with work in migrant shelters, is now focusing on following all of the asylum-seekers' cases. Several women and kids have been released while their cases play out in immigration court. One man detained from the caravan said agents asked him if he had to pay to join it and whether anyone had forced him to join; he said no to both questions.

"Their journey is not over. The trials and tribulations are far from over,” Mensing said. “The United States attacked them in Mexico, and they'll keep attacking them here." ●

CORRECTION

Alex Mensing, Pueblo Sin Frontera's project director, studied in Argentina as a high school student. An earlier version said he studied there in college.