There’s a joke about Terry McAuliffe. He made it up himself.

“Lot of history here,” he’ll tell guests at the Virginia Executive Mansion. “Our first governor, Patrick Henry. Our second governor, Thomas Jefferson. And now” — he pauses, and by this point he’s already smiling — “TERRY MCAULIFFE! Is this not a great country we live in?!”

Somehow, you don’t need to know everything about the Virginia governor, or his life in politics, to understand the unlikely comedy of his name on a list with an American revolutionary and a Founding Father. But if there is something improbable, even innately funny, about McAuliffe in statewide elected office, the governor doesn’t just know it — he’s laughing along. He’s in on the joke. “Mika! Mika! Mika!” he yells to Mika Brzezinski at the end of a hit on Morning Joe. “I want to say one thing to Mika. Think of this tonight when you go to bed, Mika! Our first governor, Patrick Henry…” And just like that, before 9 a.m., he’s cracking himself up on live TV.

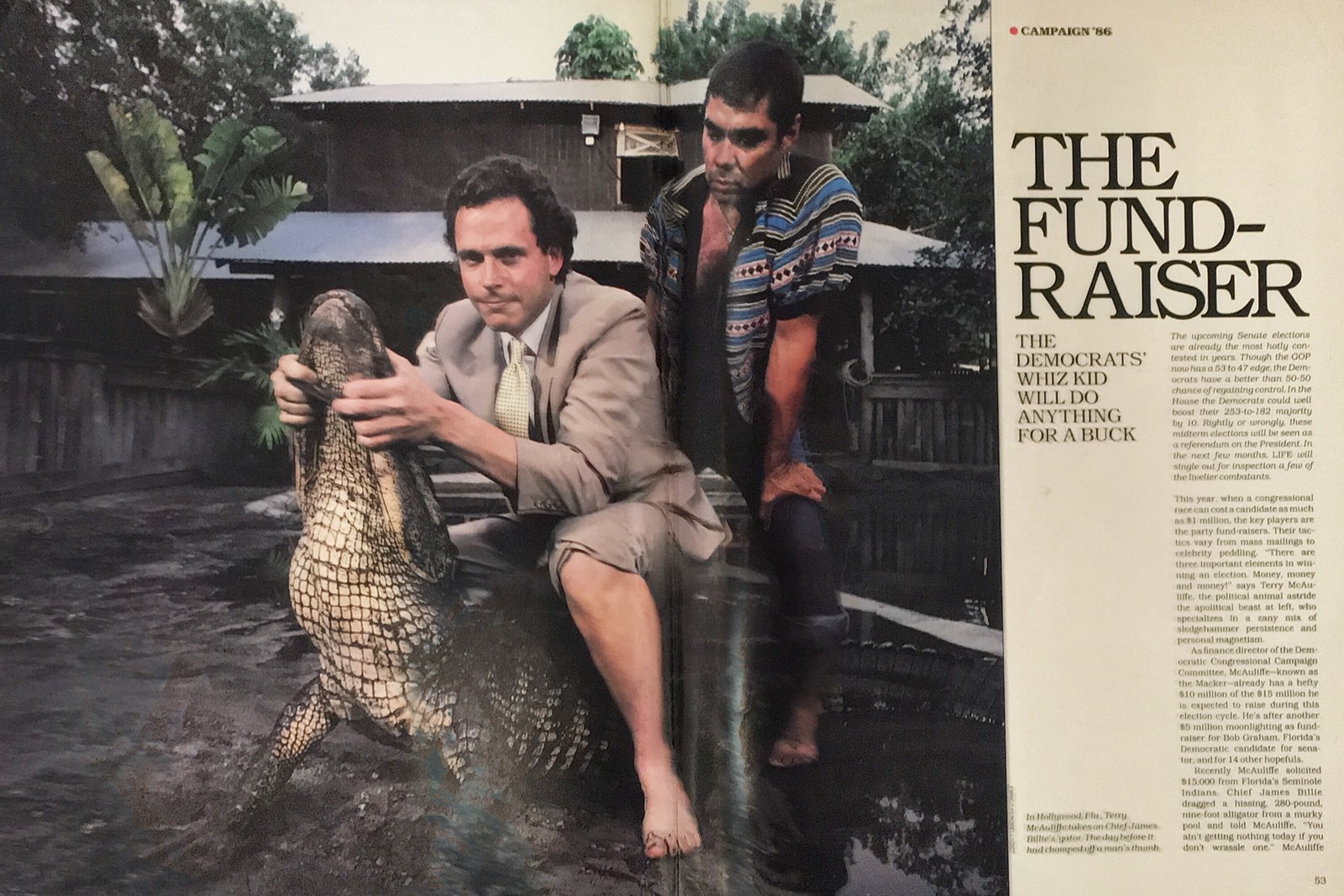

For a long time, there was one story about Terry McAuliffe, and it went something like this: record-breaking fundraiser, Bill Clinton’s best friend, fixture of Washington, wealthy by way of business by way of politics (screw optics!), an all-out all-the-time Democratic Party chairman who never napped, hardly slept, always had fun. It started, perhaps, in Syracuse, New York, at age 6, when he worked his first fundraiser for his father. (“Terry,” he told his son, “if they don’t give you the money, they don’t get in the door!”) Or maybe it was in 1980s Washington, where he said he made as many as 100 calls a day, many on a clunky cell phone, driving through the city in his windowless, open-air Jeep. By the end of the Clinton administration, he was known as a man who could charm any donor and would do anything for a check. (See: wrestling an alligator for $15,000 from the Florida Seminole tribe.) (Also see: selling Clinton inaugural memorabilia on QVC.) His nickname, “the Macker,” became a kind of onomatopoeic shorthand for the fundraiser and political operative he embodied: a backslapper, a glad-hander, a man who loved the game and didn’t pretend otherwise; who got along with people like Bill Clinton because “to us,” he once said, “the glass isn’t half-full, it’s overflowing”; and who named his memoir, of all things, What a Party! — “because the bottom line is that you gotta have fun in life!”

In 2017, at age 60, Terry McAuliffe is “His Excellency, the 72nd governor of the Commonwealth of Virginia.” He is a leader in the party, Governing magazine’s Public Official of the Year, popular in his state. He will leave office in fewer than 50 days as a possible presidential candidate. He is seen as both the most progressive governor in Virginia history and the best in economic development, racking up a record-breaking $18.7 billion in new capital. This summer in Charlottesville, he found himself at the center of a national inflection point, when he told white supremacist and neo-Nazi protesters what President Donald Trump would not. (“There is no place for you here. There is no place for you in America.”) He has surrounded himself with a team of political operatives and informal advisers, including top aides from Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign. And last month, voters in Virginia elected his hand-picked successor, Lt. Gov. Ralph Northam, a candidate who once said that when “people ask me if I am going to continue what Terry McAuliffe has been doing,” his answer is nothing less than this: “Damn right, I am!”

There are obvious differences between McAuliffe’s last four years and the previous 40. He’s got all the trappings of high office now (the title, the black car, the helicopter). His accent, an indefinable Syracuse-southern-folk drawl, is perhaps more Virginian than before: final R's and G's are dropped (it’s “hurtin’,” never “hurting”), long I's and short A's are drawn out into new vowels (“ecaahnomy,” not “economy”). And day to day, the requirements of the job itself mark a significant shift for McAuliffe: Before the Charlottesville press conference, his most well-known TV appearance would have been on Morning Joe, in June 2008, when he celebrated Hillary Clinton’s primary win in Puerto Rico by wearing a Hawaiian shirt and hoisting a handle of Bacardi on air.

But in more moments than not, today’s governor looks and sounds just like the Macker.

The fundraiser who said he’d “stop at nothing to try to get a check from you” now spends his time courting business to the state with the same vigor. The chairman who led the party as its “chief cheerleader” now heads one long continuous pep rally for Virginia. The entrepreneur who started an estimated 30 companies — maybe simply because of an impulse to, as he once said, “have 25 balls in the air at the same time” — is still trailed by headlines about his business dealings.

"People want to be with winners. They don’t want to be with whiners."

And the man who described his “bottom line” as “you gotta have fun” leads the state with the same management style. To McAuliffe, it’s not just “fun.” It’s a philosophy for governing.

“You want to move people with you? You’ve got to have fun doing it,” McAuliffe says in an interview, seated on the back patio of the Executive Mansion. “People want to be with winners. They don’t want to be with whiners. Too many lemon-suckers in this business!”

The approach, to the surprise of many who would have never predicted McAuliffe in statewide office, has translated to a distinct economic message and legislative wins in a state that is trending liberal but still controlled by a Republican assembly. Yet it also makes him, then and now, an embodiment of the very thing many progressives have rejected over the last few years: an establishment insider; a creature of Washington; a pro-business, corporate dealmaker; a Democrat known perhaps best of all as a loyal Clintonite, all at a time when Bill Clinton’s legacy is under new scrutiny and Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign continues to divide the party.

But if you ask McAuliffe, he will tell you he’s found a “template” for the rest of the party. And if you ask the inner rungs of his Rolodex — a loyal circle of friends, former aides, and donors now eyeing his future in a possible presidential race — they will return again and again to the same point: that the qualities that made him a great fundraiser are the same ones that have helped him find success as governor, and set him apart in substance and style.

To start, they say, he may be the only guy in Democratic politics still having any fun.

On a Saturday afternoon this summer, a small troop of volunteers assembles in the Washington suburb of McLean, Virginia, ready to canvass the neighborhood for Ralph Northam. Near the front of the living room, a supporter is running through instructions: “So when we're knocking on a door,” she tells the group, “I'll just quickly go through the script with you—”

All at once, the presentation comes to a halt, get-out-the-vote scripts are put aside, and the living room's collective center of gravity shifts as Terry McAuliffe lets himself in through the front door and pops into view, his voice booming: “Hey! HEY! Hello, everybody! How you all doing today! Good crowd! How are you! Great to see you again! How ya been! How you doin', everybody! Fired up! Yeah! We got a whole crowd here!"

"People like me because I'm a man of the people," he once said, "a hustler."

The next day, McAuliffe blasts into a small conference room, late for a bill signing. He circles the table for hellos. In the back, a woman turns to her friend: “He must have, like, five energy drinks a day.” Later that week, he joins tribe leaders at the Mattaponi Pow Wow in West Point, Virginia. After the official ceremony, intricately dressed performers move into the reservation circle, dancing in tight, coordinated movements. Suddenly, McAuliffe darts back into the circle, jogging in place, clapping to his own quick rhythm while the Mattaponi drums beat slowly behind him. “Alright," an aide says, chasing after him, "I guess we're going dancing again."

This is how the governor enters a room: in a whirlwind, tearing through it, jolting the people around him awake. This particular week was a normal one for McAuliffe: 51 events across Virginia, plus a quick trip to New York.

McAuliffe has always moved at a pace of "one thousand miles an hour," as he put it in 1998. “People like me because I'm a man of the people," he once said, “a hustler.” His approach is all-out to the point of extravagance. At the age of 14, he started his own driveway sealing business and built it into a small empire. (“I used to make my mother answer the phone, ‘McAuliffe’s Driveway Maintenance.’”) His classmates at Bishop Ludden Junior-Senior High School elected him president in 8th, 9th, 10th, and 11th grade. As a senior, McAuliffe mounted a bid for student body president. On the day candidates made their pitch, he and his friends borrowed two golf carts, stuck police lights on top, dressed up in trench coats and sunglasses like Secret Service agents, and, lights flashing, came flying into the Bishop Ludden auditorium to the sound of Hail to the Chief. “The place was going berserk,” says Duke Kinney, one of McAuliffe’s best friends since kindergarten. “Behind our school was this big hill called Hawk's Hill. And Terry finishes his speech with, 'If it takes a keg of beer on a Friday night up on Hawk's Hill to win this election, I'll sponsor the keg of beer!’” (“He won that in a landslide,” Kinney says.)

As a young fundraiser, he’d tell his deputies to “scorch the earth!” and “be animals!” He’d call donors every year on their birthdays. He’d send drugstore valentines every Feb. 14. When he started to work on his memoir, McAuliffe’s coauthor, Steve Kettmann, ended up moving into the family’s guest house for weeks at a time just to keep up with the pace. (“He didn’t sleep for like a year,” McAuliffe says of Kettmann. “He hated it! But he had fun!”)

Staffers who have served as McAuliffe’s body man, trailing him each day from early morning to late evening, can’t recall him ever taking a nap. More often than not, they say, on long car rides or flights back to Washington, they’d be the ones asleep. “We had a game where he would find my seat, write a card that said, ‘You're an embarrassment,’ put that in my lap, and then take a picture of it and send it to the entire DNC,” says Justin Paschal, his former body man and longtime close aide.

“Few people work harder than me,” McAuliffe says now. “I will outwork you.”

The job of governor, as he sees it, is a “perfect” fit for his personality, work ethic, and affinity for executive roles. “I'm happy doing whatever I'm doing. I really am.” But governor — "it's the perfect job for me. Most people will say, 'This is the perfect job for Terry.'" He couldn’t be a US senator or a member of Congress, he says. “I could never do it. It’s just not who I am. I know who I am. I don’t mean it negatively. It’s just I like executive roles."

But governor — "it's the perfect job for me. Most people will say, 'This is the perfect job for Terry.'"

The approach has helped him rack up some high-profile achievements, which he will list for you in rapid succession: a long battle to restore voting rights for 206,000 felons; a four-year campaign to court $20 billion in new capital; a series of investments in education, childhood hunger, and cybersecurity. At the canvass kick-off in McLean, he quickly launches into a speech about his tenure, punctuating every other point with his own system of exclamations: “Folks!” he says. “Truly historic!” “Truly, truly extraordinary!"

"You know the numbers!" he says.

You will hear dozens of them in a Terry McAuliffe stump speech, which is not so much a speech as a list of personal benchmarks, curated by the governor and his staff: stats, achievements, and special designations that might apply to McAuliffe ("most traveled governor in America!"), his administration ("most vetoes" in state history, and not one overridden by Republicans!), and his policy efforts (more voting rights restored than under "any administration in the history of the United States of America, folks!"). McAuliffe seeks out these distinctions, asking his staff to research and vet and verify each one. “Before I’m allowed to say it, these guys have to fact-check it,” McAuliffe says. If he is the first governor to visit some far-flung part of the state, aides clip and save the coverage in the local papers. “Eighty, 90, 100 events now,” McAuliffe says. “We enjoy it… We love it!”

No distinction is too small. This is “Gov. Superlative,” says Brian Coy, a longtime aide.

McAuliffe gets worked up about nearly every aspect of the job. Routine bill signings are "great!" — "really great!" Speeches (he gives about six to eight a day) always get “a little flavor.” Every vetoed Republican bill is a mark in the W column. "They can't beat me on the vetoes!” he says. "We had one of my favorite Democratic senators, a new one — the [Republican] leader went to him and said, Please give me one vote. I just want to beat the guy once.” Even McAuliffe’s failures are “spectacular” — namely, his five attempts to push Medicaid expansion through a Republican legislature. He’s made a habit out of mentioning the defeat. “The one thing I’ve tried — and I apologize, I’ve been a spectacular failure at it — is getting Medicaid expansion done,” he tells the crowd in McLean. “It hasn’t been for want of tryin’.” His point, he explains later, is that “I work my heart out. People fail in life, you know? And admit it! But you tried.” (McAuliffe plans to make a sixth attempt in his final budget as governor, hoping that last month’s sweep of down-ballot Democratic wins may convince GOP lawmakers to bend.)

For Republicans like Emmett Hanger, a 69-year-old who has served for more than three decades in the General Assembly, the governor’s style is “always out there,” he says after a pause. “He tends to be just borderline flamboyant. But, yeah... He’s fun to work with.”

This is perhaps most true when McAuliffe is entertaining at the Executive Mansion, a blonde brick Federal-style building that sits atop a sweep of lawn in downtown Richmond. It’s not unusual for the governor and his wife to host two receptions in one night. He will happily give you a tour of the house, bounding up the stairs — two steps at a time — to show off this painting or that architectural feature. On the first floor, the bar has become a permanent fixture, lined with gleaming bottles of vodka, rum, gin, whiskey, and liqueur. A kegerator sits in the back corner. The handle is engraved with his name. Music fills the room via Pandora stations like “Jimmy Buffett Radio” and “Happy Hipster Holiday.”

On this particular night, the day after his McLean visit, McAuliffe gives a typical welcome to a delegation visiting from out of state: “I'm the only governor to install his own kegerator over here,” he tells them. “Take advantage! We've got Stone IPA in there! I just opened our 199th craft brewery! Three hundred wineries now here in Virginia, believe it or not! We just moved into fifth place: California, Oregon, Washington, New York. I don't count New York — they use their grapes for jam. We don't do that," he says, and the room laughs along. “We're movin' to number one! Forty-six distilleries! Eight varieties of oysters! Virginia's for lovers! You get it!"

“Alright," he finally yells.

"Crank up the music now!”

In early 2009, at the start of the Virginia governor's race, Michael Krizic landed his first gig in politics.

As a “tracker” for Brian Moran, one of three Democrats running in the primary that year, the 27-year-old aide had one job: to attend and videotape every McAuliffe event. Moran expected a big screw-up: This wasn’t just a first-time candidate. This was the Macker — rogue, wild, and untested.

Over the course of that spring, two things happened.

The first started right away: McAuliffe introduced himself to Krizic, and at every event that followed, each time the young operative would set up his video camera, McAuliffe would chat him up. Before the annual Jefferson-Jackson Dinner that year, Krizic recalls, they sat talking for 15 minutes — "longer than we should have," he says, “but in a good way: asking about me and vice versa, just a conversation — which became kind of normal. Each conversation got a little more in-depth.” By the end of the race, McAuliffe had befriended his own tracker.

Krizic says the second thing happened more gradually. As he chased McAuliffe up and down I-95, putting close to 15,000 miles on his car, Krizic saw a candidate who both affirmed and challenged the “preconceived” Macker image. “There’s the wild fundraiser offering rum shots on TV," he says. “And I definitely caught instances of that." But the frenetic energy also came with a discipline and work ethic that surprised his rivals.

"We were just waiting for him to mix up Abingdon and Arlington," says Moran, who now serves in the McAuliffe administration as Virginia’s secretary of public safety. “He was going to mess up. And he never did. By the end of the campaign, I thought, Well, this guy's serious.”

McAuliffe has spoken in the past about the way people, in his words, “pigeonhole” him. “I’m known for raising more money than any man alive. But you know what? I’ve always known about these issues,” he said in 2009, citing his many past appearances on Meet the Press. (He now credits his upbringing in Syracuse, where he says his parents taught him early on that “your job is to put your hand out and help someone up the rung of that ladder,” though for years, he talked more often like an operative than an elected official: “I stay away from issues,” he said in 1999. “I do mechanics, not message,” he said in 2004.)

As a candidate in Virginia, McAuliffe's transition to elected office did not come without struggle. He approached the 2009 primary, a three-way race against Moran and state Sen. Creigh Deeds, with the same intensity as with any other endeavor, recruiting celebrity surrogates from Biz Markie to John Grisham, raising bags of money, decking out events. (A New York Times magazine story recounted his campaign’s presence at the 2009 Jefferson-Jackson Dinner: a McAuliffe banner, a McAuliffe marching band, 39 McAuliffe dinner tables, 2,500 McAuliffe-themed fortune cookies, 300 McAuliffe glow sticks, and two McAuliffe after parties.) His political style and connections also, of course, became his biggest vulnerability. At that point, he’d lived in Northern Virginia for 17 years. Still, his opponents easily cast him as an outsider and carpetbagger: Moran, his sharpest critic at the time, described McAuliffe as a resident of "Park Avenue" and "Hollywood” and a product of the “corrupt political establishment," beholden to "big-money 1990s politics" and unsavory contributions — including, Moran eagerly noted at the time, a $25,000 donation from New York’s own Donald Trump.

After he lost the primary in 2009, McAuliffe never really stopped running. He hired Levar Stoney, a prominent Democratic operative in Virginia who now serves as the mayor of Richmond, to help prepare for the next race. From 2010 to 2013, the two of them spent nearly every day together, with Stoney driving and McAuliffe in the passenger's seat, traveling to pockets of Virginia where he had never spent much time. They went to chicken festivals and coal mines, met with fishermen on the shore, attended local party dinners. McAuliffe needed to build relationships outside the Washington suburbs. (This was a man who, in 1988, told aspiring campaign operatives that one of the good things about fundraising is "I'm not in Des Moines, Iowa... It's the cities of San Francisco, Los Angeles, Houston, Dallas, New York, Miami, Chicago.") Early on, progress was slow. “He hadn't really gotten around Virginia,” Stoney says. "We had a lot of doors shut in our faces. Folks would not return my phone calls. Folks would not return my emails. But, slowly but surely, we chipped away at it."

In both campaigns, McAuliffe also had to reckon with the unpleasant moments of his long career in politics and business. Over the course of the 1990s, he was questioned by congressional and Justice Department investigators; was accused by at least one donor of a “quid pro quo" scheme in the Clinton White House; and figured as a central player in a federal investigation into an illegal fundraising scheme involving the Teamsters union, the DNC, and Clinton’s 1996 campaign. Many of the inquiries involved the same mix of politics, money, and influence that has long been associated with the Clintons. Others were more unsavory: Court documents named McAuliffe in a list of investors backing a man who pleaded guilty to a scam that took advantage of the terminally ill. (After the investment was reported, he donated those profits to charity. His aides said McAuliffe "never would have invested" had he known the nature of the man's business activity.)

Last year, reports named McAuliffe as the subject of an FBI investigation — the scope and focus of which were unclear, but possibly concerned donations to his campaign and the Clinton Foundation from a Chinese businessman. (“I don’t think there is anything there,” McAuliffe says when asked if he is aware of any updates to that inquiry. “He was a legitimate donor.”) Meanwhile, his involvement in an electric-car company called GreenTech Automotive, also championed by Hillary Clinton’s brother, continues to generate headlines over the company’s use of a special visa program to help secure foreign investment. McAuliffe left GreenTech in 2012. A year later, there was news of an SEC investigation. His aides denied any knowledge of the inquiry at the time, and charges were never brought forward. Just last week, a group of Chinese investors sued McAuliffe and others, alleging that they now face deportation because GreenTech did not create enough jobs.

For McAuliffe, the 2009 and 2013 races were an opportunity to develop his own approach to Democratic policy. His message to voters always hinged on economic development — "jobs! jobs! jobs!" he says now — but in the eight years since his first campaign, McAuliffe has also refined that focus into an overarching framework for governing. Every issue — big or small, social or not — is tied, in his eyes, to creating jobs, courting businesses to the state, building what he calls the “New Virginia Economy.” It's not an explicitly ideological message. It's not grounded in the big debates of today's Democratic Party. It offers no outright position on left vs. center, establishment vs. grassroots. As McAuliffe describes it, a better workforce is a “moral” imperative.

"I think job creation is the single most important value a governor could have. To me, it is the core issue of what government is about."

“I make the economic a value statement,” he says.

His view of governing goes something like this: You can't give people opportunity if they don’t have good jobs. And you can't get people into good jobs if they can't access good health care, or get a good education, or get to work on good roads and bridges — and so on and so forth. A strong economy, as McAuliffe explains it, is as much about LGBT and abortion rights (because businesses won't come to a state that “discriminates”) as it is about a lunch program for low-income students (“because you cannot build a workforce unless you have a great education system, and you cannot have a great education system if your children can't learn because they're just plain hungry”).

“Everything comes from a value proposition,” he says. “Where are you morally on the issues? I think job creation is the single most important value a governor could have. To me, it is the core issue of what government is about.”

To make that point, there is a lot of talk from McAuliffe about “leaning in” and “doing the right thing.” He is always “leaning in” on something — he’s “really leaned in” on cyber, “leaned in hard” on childhood hunger, “leaned in double hard” on voting rights — even rocking forward on his feet as he says it. “Never once have we put our finger up in the air to see where the polls were,” he says. “Lean in on what you think is right, and let the chips fall where they may.”

Inside the state, progressive activists might balk to hear that from McAuliffe. While they were heartened by the governor’s fight to restore voting rights for felons — an initiative that previous Democratic governors did not pursue or wrote off as impossible — Virginia liberals have taken issue with parts of his record. One sticking point is McAuliffe’s ongoing support for two natural gas pipeline projects in the state. Another: his 2016 deal with the National Rifle Association to, in exchange for other gun restrictions, recognize most out-of-state concealed-carry permits.

The two pipelines, called the Atlantic Coast Pipeline and the Mountain Valley Pipeline, are bitterly opposed by left-leaning activists. “A lot of progressives and environmentalists, including myself, feel like he’s backtracked on what he ran on in 2009,” said Lowell Feld, a liberal writer and advocate in Virginia who supported both McAuliffe campaigns and, at the time, considered him a more progressive candidate than most Democrats who have run statewide in Virginia. Since McAuliffe took office, Feld says, that view has diminished: Gun control groups, for instance, were “livid” with him last year over the NRA deal.

It might also be difficult to find progressives who share the governor’s raw excitement for economic development, or connect with the slow climb to $20 billion in new capital, tracked in press releases about 15 new jobs at a Pittsylvania County packing company, or the new Facebook data center in Sandston, Virginia.

“He loves sitting down and cutting a deal and bringing some jobs to Virginia,” Feld says. “That's fine if he's into that. It’s not my theory of economic prosperity.”

McAuliffe, however, believes he’s landed on a model for Democrats nationwide. "I’m clearly the most progressive governor in Virginia," he says, "but I’m also the biggest economic developer. We’ve merged those two. And I honestly think this is a template for the Democratic Party."

On the subject of the party's future, with many still consumed more than a year later by the long and fraught primary between Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders, he dismisses the suggestion that Democrats are moving en masse toward the far left. “There isn't one message," he told a group of mayors at a conference earlier this year. “People always talk about ‘litmus tests.’ What are your values? I know that what I need to do in Virginia might be very different from what [a] mayor needs to do in South Carolina,” he said. "Quit telling people what they oughta do.”

As for Sanders himself? “Everybody’s got their own styles," McAuliffe says.

“I have to deliver. I am a governor. For me, I just can’t give speeches."

On Jan. 13, Northam will take the oath in Richmond, and McAuliffe and his family will move back to Northern Virginia. “I think Dorothy would like a week or two,” he says. “But that would be it.” McAuliffe is not one to take much of a break. An offhand vacation suggestion — to spend some time sitting on the beach — is met with a vigorous shake of the head: “Oh gosh, no. No, no. I’ve got to do something. No, no, no. I don’t do that stuff.”

His view of relaxation is limited largely to reading and action movies: “Cars crashing through houses and guns going off — and it drives Dorothy crazy, the noise.” But not much else will calm down McAuliffe’s “engines” — which are, he notes, “always full-throttle.”

For now, the governor has a few projects lined up. He’ll invest more of his time in the new redistricting effort run by President Barack Obama and former attorney general Eric Holder. He also intends to campaign on behalf of Democratic gubernatorial candidates in 2018. But for McAuliffe — who will not, or cannot, stay idle for long — the next big thing might also be a presidential campaign.

A defeat for Northam would have cast real doubt on that possibility — including among his own supporters and aides, who viewed the election as a critical test of McAuliffe’s success in office. Throughout the race, aides and advisers kept close daily watch on the Northam campaign, stepping in with a heavy hand after the emergence of an unexpected primary challenger, Tom Perriello, to ensure that no high-profile supporters defected.

Former Hillary Clinton operatives like Robby Mook, her campaign manager, and Michael Halle, another senior aide, are among the formal and informal political advisers now around the governor. (Mook, who managed McAuliffe's 2013 campaign, is not currently on payroll, an aide said. Halle worked this year on the Virginia Democratic Party’s coordinated campaign, acting as a liaison of sorts between McAuliffe and the Northam camp.) It’s a close-knit political orbit made up former aides and decades-long friends, donors, fundraisers, and old colleagues. Some of those people have been talking for months already about 2020. McAuliffe himself is more circumspect. When people bring up the subject, it’s almost always a “one-sided conversation,” friends say. (He will maybe only joke, as he did with one donor, “You just wait, it’s gonna be big!”) But even before Northam’s victory last month, some McAuliffe donors were spreading the word among Democrats they should assume with some certainty that he’ll move toward a run.

He will maybe only joke about a presidential bid, as he did with one donor, “You just wait, it’s gonna be big!”

Those supporters also acknowledge that McAuliffe faces big challenges in a Democratic primary: What early-voting state could he win? What would voters make of the string of inquiries around his private businesses? Does even more opposition research await? (There is a creeping sense among some Democrats that it does.) And what would voters think about a candidate who comes to the table with a close link to the Clintons? With a message about economic development? A record that has disappointed climate and gun control advocates? (Some are already talking amongst themselves about ways to leverage his national ambitions — forcing McAuliffe, or Northam, to take a stand against natural gas pipelines.)

Friends and former aides say McAuliffe is aware that his association with the Clintons could make it difficult to gain traction after last year’s presidential campaign. Even now, there are moments when the governor can tiptoe around the Clinton name, clarifying that a comment about admitting your failures is not a shot at Hillary — or wondering aloud why reporters have asked him to weigh in on her next political project, a PAC she formed earlier this year called Onward Together. “I didn’t even know the name of the PAC!” he says.

Over the last four years, some of the critics who raised questions about McAuliffe have been won over. His 2009 opponent, Brian Moran, quickly made the transition from rival to friend and cabinet member. The 58-year-old official now characterizes attacks against McAuliffe, particularly those aimed at his businesses, as “spaghetti against the wall” that “never stuck,” Moran says. “I’m sure that if he goes on, they’ll try it again.” (In which case, he adds, “I would be on the front lines for him. I’ll be in New Hampshire. I’ll be in Iowa.”)

If McAuliffe does make the jump to 2020, he could find financial support from some of the party’s biggest donors, perhaps enough to power his campaign past the early primaries and caucuses. He is close with Haim Saban, a major Clinton funder, and he already counts Sean Parker, the Virginia native and cofounder of Napster, as his largest campaign contributor.

But beyond money, McAuliffe has something else on his side: a vast and loyal network of friends. Whether they are donors or fundraisers, old colleagues or staffers, union leaders or voters he’s met along the way, they have also, more than likely, become friends.

To McAuliffe, if it’s not fun, you can't motivate people: work turns into drudgery, staffers lose commitment, energy fades. No one wants to be “with you.” Make it fun, and they do.

Every elected official has a political network, and every political network has its own distinct currency. For the people around Barack Obama and his presidential campaigns, loyalty functioned as a sort of devotion: a true belief in the candidate, his magnetism, and the power of his message. With the Clintons, loyalty was a measure of proximity. And true proximity to the Clintons was a rare commodity — guarded by those who had it, coveted by those who didn’t.

With McAuliffe, proximity is immediate, and loyalty is developed on a personal level.

“Terry is particularly good at keeping his relationships when there isn’t a transaction to be had,” says Michael Kempner, a Democratic donor and fundraiser who bundled millions of dollars for Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama. “People appreciate the genuine friendship.”

Former aides describe McAuliffe with words like “mentor,” “big brother,” “second family,” and “very good friend” — “but, like, an actual friend” — and that’s whether you are Bill Clinton, they say, or Barbara Hurd, the receptionist at the DNC — all of which makes his political network one that is “very, very, very, very large.”

“Terry does not let people get out of his universe,” says Alecia Dyer, who started working as a secretary and scheduler for McAuliffe when he was 23 and stayed with him until he left the DNC in 2005. “He remembers everything.” During an interview on what happened to be his birthday, Duke Kinney, the childhood friend from Syracuse, paused to answer a call on his cell phone. McAuliffe’s singing came through in the background: “Happy birthday to you!” For Paschal, the former body man and longtime staffer, his sharpest memories with the governor are also the best and worst of his life: McAuliffe threw his engagement party, walked his mom down the aisle at the wedding, became godfather to his son, and in 2015, received one of the first phone calls that Paschal made after his wife lost a battle with cancer at the age of 39.

“Once you've worked for Terry McAuliffe, you always want to work for Terry McAuliffe,” says Paschal. The explanation for this you hear most often is some variation of “he always makes it fun.” To McAuliffe, if it’s not fun, you can't motivate people: Work turns into drudgery, staffers lose commitment, energy fades. No one wants to be “with you.” Make it fun, and they do. The question of whether a book like What a Party! could be used against him politically — which it was — interests him less, for instance, than whether it kept you entertained: “Have you laughed out loud a couple times? That’s always real nice.” People like to be around McAuliffe, and he very simply likes to be around people. Friends say he got it from his late father. Jack McAuliffe, much like his son, had an “infectious personality” and “never hesitated to have a cocktail,” says Kinney, the childhood friend. (One time, traveling home together from the Democratic Convention in 2000, Kinney went to check the gate while McAuliffe’s dad waited in the airport bar. When he returned, “he goes, ‘Duke, you know Paul? The bartender here!’ Jack's acting like he's been best friends with this guy his whole life. He met him five minutes ago.”)

It’s part of the reason McAuliffe became close with the Clintons, who, he says, “would call my staff and say, ‘Let’s get Terry down here’” during what he calls “the worst times” — i.e. the family ski trip after the Monica Lewinsky scandal. “Brutal,” he adds. (In the foreword to the audiobook of McAuliffe’s memoir, Hillary Clinton flatly describes the White House as a “very lonely and desolate place”; McAuliffe, she writes, acted as the antidote.)

It’s also part of the reason some see McAuliffe as a serious contender in 2020, despite his vulnerabilities. Michael Trujillo, a California-based operative who worked for Hillary Clinton, remembers McAuliffe taking out 30 or so interns for dinner in San Francisco one night during the 2008 campaign. “For those kids, it was amazing,” Trujillo says. “He has stories like that all across Iowa, New Hampshire, South Carolina, and Nevada.”

It might be a bit much for some, or too hard to believe. It was, at least at first, for the coauthor of McAuliffe’s memoir, writer and former magazine journalist Steve Kettmann. “I have enough of a reporter's brain, where you're kind of always asking yourself, what am I missing here?” he says. “What's the other side of this guy? He can't be this upbeat. He can't like people this much. He can't be that interested in talking to everyone.”

One night, a few months into the project, they were together in the guest house, playing cards. It was late, 3 or 4 a.m. McAuliffe was cracking jokes, same as always — and that’s “when it all kind of clicked,” Kettmann says. “It just struck me: This guy is exactly the same now. This is who he is. There's no subterfuge. There's nothing except who he is.”

“I’ve probably been at it longer than any person, ever,” the governor says, leaning back in his seat outside the mansion.

“I mean, since 1979!”

“I mean,” he goes on, “Maureen Dowd did a piece on me in ’88 and said, This man’s lasted longer than anyone else.”

“1988!”

In the long arc of his political career (“longer than any person ever”), McAuliffe has weathered scandal, stretched the limits of brands like “the Macker” and “Bill’s best friend,” and somehow come out on the other side with a serious record, credibility inside Richmond, a governing style that looks and sounds like no other politician, and the possibility of a presidential run.

“Look at the experience I had. A kid from Syracuse, NY, ended up best friends with the president and the first lady.” And now he’s here. “I pinched myself every day,” McAuliffe says. “I mean, I started out — I did it myself. It wasn’t like anybody handed me anything.”

In his final year as governor, though, McAuliffe still gets a laugh out of the line about Patrick Henry and Thomas Jefferson. There’s still that same glint of humor, or disbelief, about the fact that he is the same as ever, both His Excellency Gov. McAuliffe and the Macker.

It was there on the day of his inauguration, a gray and rainy morning in January 2014, when a grinning McAuliffe arrived to take the oath, his friends flashing bemused smiles from the crowd. After the ceremony, the new governor leaned over the stage to guests gathered below. “Did you have fun?!” he hollered out to one. “Are you ready to dance?!” he asked another.

And it was there again four years later, on the night of the governor’s race last month, when McAuliffe, still grinning, took the stage at the victory party to cheers and applause while the '90s R&B song “Return of the Mack” came pounding through the ballroom speakers.

Return of the Mack... It is!

Return of the Mack… Come on!

Return of the Mack... Oh my god!

You know that I’ll be back... Here I am! ●