‘If the government is to have any chance of meeting its target of 300,000 new homes a year it cannot simply rely on traditional methods of construction.’

These are the stark words of Labour’s Clive Betts, chair of the Housing, Communities and Local Government Committee.

Last week the influential group of MPs demanded a fresh and urgent focus on building prefabricated homes. In his call-to-arms, Betts said both the government and the industry needed to shake off their bonds with long-tested building practices.

Advertisement

MMC is billed as quicker, greener and potentially cheaper than traditional methods

‘Reluctance is understandable,’ he noted. ‘The perception is that the building innovations of the 60s created homes that failed to survive half a century, while rows of Victorian terraces are still standing.’

A key first step, Betts concluded, was to prove the ‘quality and longevity’ of homes already built from modern methods of construction (MMC).

Yet despite his fears over industry foot-dragging, Betts could be pushing at an open door.

In the last month, a series of announcements has lent weight to the assertion that, after years of talk, MMC – which is billed as quicker, greener and potentially cheaper than traditional methods – is at last moving into the mainstream.

In May, it emerged that Places for People had agreed to buy 750 factory-built homes for £100 million – the biggest investment in modular by a housing association to date.

Advertisement

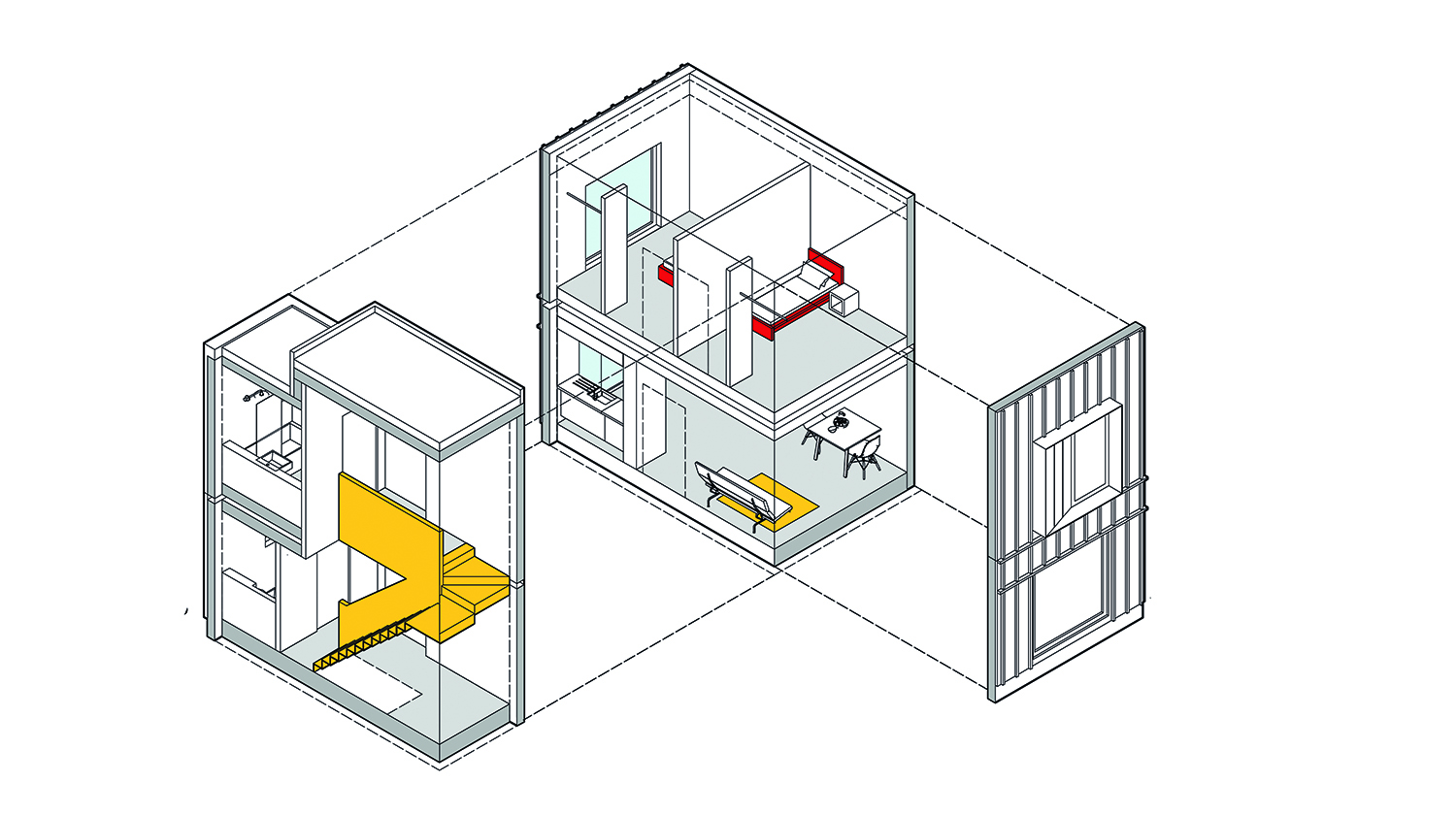

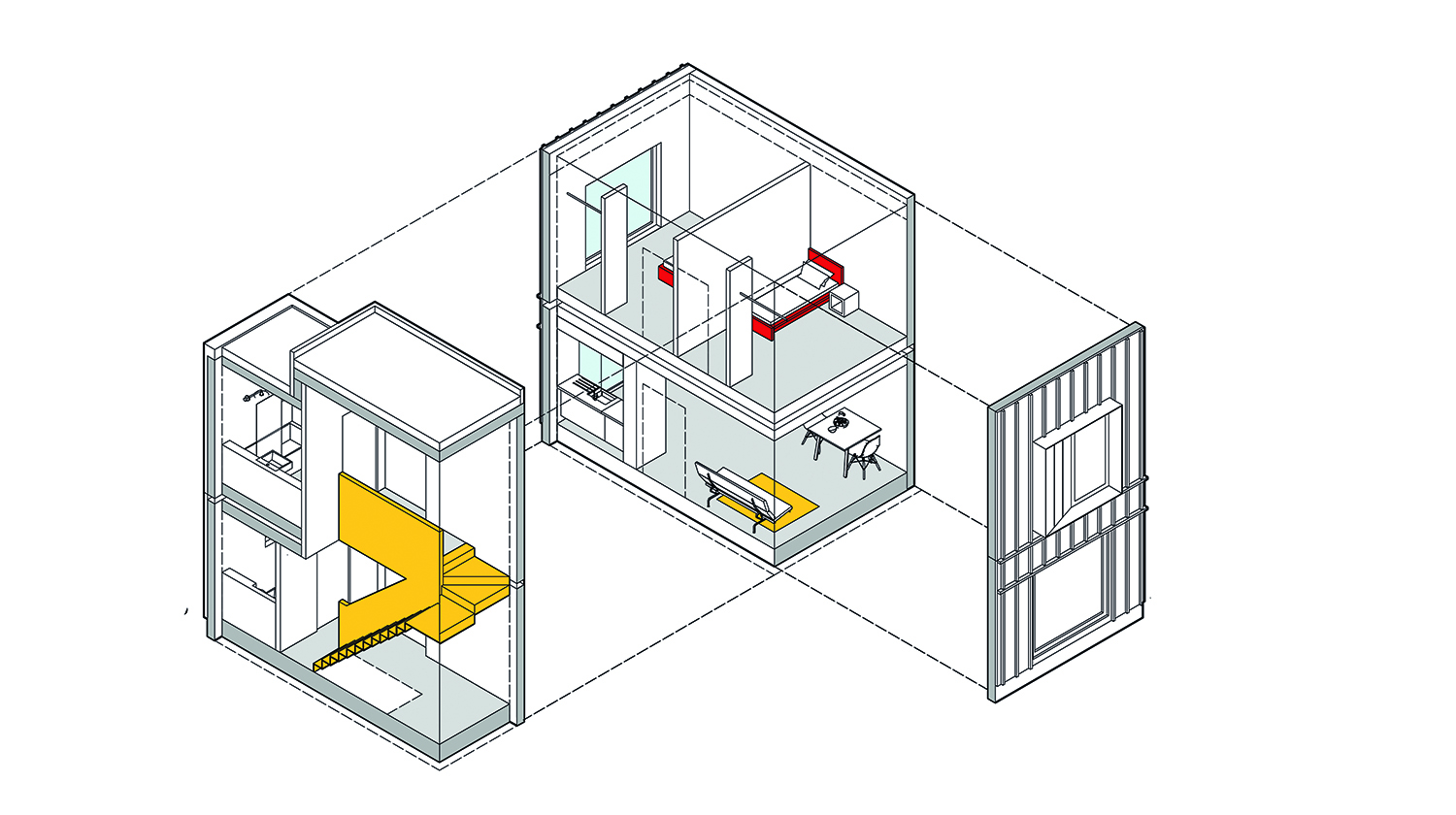

2b3p b house exploded facade sheet title

Engine House, ShedKM’s modular, affordable housing concept in development with manufacturer Ideal Modular Homes. A prototype model is expected to be completed by the end of the year

And then there are the 406 modular homes being developed on behalf of Homes England by regeneration specialist Urban Splash and architect Proctor & Matthews at the Cambridgeshire new town Northstowe, underpinned by a major financial deal between Urban Splash and Japanese housebuilder Sekisui.

Others keenly pursuing MMC projects right now include Swan Housing Association and IKEA, which recently announced it was assembling 162 prefab homes in Worthing, West Sussex.

After so long with so little action, however, the industry is right to be sceptical about whether these recent announcements represent a genuine tipping point – or whether it is simply coincidence that these initiatives and deals are coming to fruition at the same time.

MMC does not dovetail well with traditional housebuilders’ business models, which keep a close eye on the number of units coming to market

It also has to be asked whether all the benefits MMC backers point to can be realised, at least in the short-to-medium term.

Hard statistics are hard to come by when it comes to the adoption of MMC. However, the most recent study, which was published at the end of last year, painted a positive picture.

The report, for the NHBC Foundation in partnership with consultancy Cast, surveyed 36 developers and found that 69 per cent were delivering housing using advanced MMC and around 92 per cent had plans to expand its use in future years. However, the report’s authors were open about the fact that survey respondents were self-selecting and therefore skewed towards early adopters.

Certainly, commentators concur that it is unlikely that a tipping point has been reached. Marc Vlessing, co-founder of Pocket Living, one of the most prominent end-users of modular products in London, is typical in his response. ‘Even with all these announcements, it remains a minority [of the industry],’ he says.

‘Are we talking a sea change? No. Are we talking about a tipping point? Well, you never know until afterwards. Is it possible that all this well-intentioned early pioneering work will lead to a tipping point? Yes. Will it take three to five years. Yes. It’s early days, but it’s helpful.’

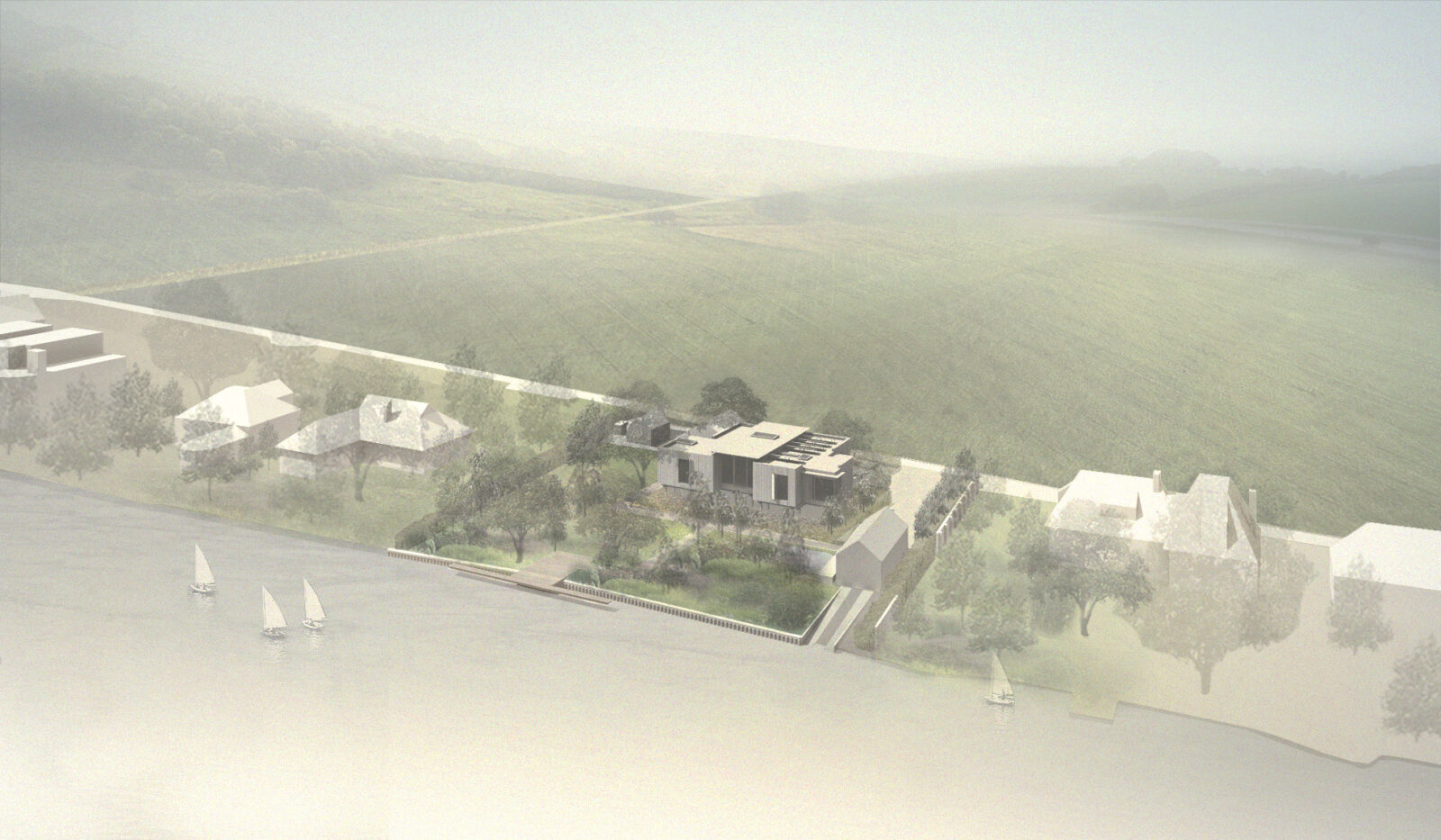

5 cookham model

March house, by Knox Bhavan Architects ‘March House is a bespoke project, specially tailored to the Thameside site and the client’s needs, but we see the innovative technology we’ve used on the scheme as a prototype for future housing projects. Once the house is complete, we are hoping to roll the cassette system out on other projects. It is easily replicable and could lead to larger multiple units and the manufacturer is keen to explore this with us.’ Fergus Knox, Knox Bhavan Architects

Richard Steer, global chairman of construction consultancy Gleeds, says MMC take-up remains ‘embryonic’. ‘I don’t think we’ve reached the tipping point yet,’ he says. ‘I’d say we’ve started the journey towards the tipping point.’

Given all the benefits claimed for MMC, it is perhaps surprising that it has yet to achieve that critical and decisive moment. On the other hand, its economic benefits are largely untested and it does not dovetail well with traditional volume housebuilders’ business models, which involve keeping a close eye on the number of units coming to market at any one time.

‘The major housebuilders have to build in line with sales,’ says Steer. ‘So, if they are going to be producing 1,000 units, they don’t want to have 1,000 units straightaway, because they’re paying out for 1,000 units and then maybe selling 10 units a month. There is an inherent advantage in the old model where they build a dozen houses and then start selling those and then move on to the next phase. Management of the speed of delivery is important.’

Even if a developer is building an apartment block, which obviously necessitates same-time delivery, and can afford to wait for sales to materialise, Vlessing says that the cost savings delivered by MMC aren’t yet readily apparent.

Modularising towers doesn’t seem to have hit its stride. It’s not cheaper and it’s not really quicker

‘It’s not clear to me yet that there is a price advantage, so you can only really do it if you care about surety of supply and quality of supply,’ he says.

Steve Sanham, the outgoing managing director of developer HUB, agrees, especially when it comes to building high rise developments using modular techniques. ‘There is definitely some momentum in MMC in individual housing projects,’ he says. ‘But I think that modularising towers, which gets talked a lot about in London, doesn’t seem to have hit its stride in any way, shape or form. It’s not cheaper and it’s not really quicker.’

That said, HTA Design is promising that its 101 George Street development, under construction in Croydon, will fully deliver two towers of 38 and 44 storeys in only 25 months. This would represent an impressive 546 new homes, built from 1,400 modules, in just over two years.

Aside from the economics, proponents of MMC also claim it has a major role to play in reducing embodied carbon in new buildings.

‘People are absolutely missing a trick when it comes to embodied carbon,’ says Ian Pritchett, managing director at off-site specialist Greencore Construction. ‘People justify it on the basis that if you’re reducing operational emissions it’s OK to put more embodied carbon into the structure. But if you can do reduce emissions and embodied carbon, why wouldn’t you?’

The argument is that the industry simply has to focus more on low-carbon materials and process – and that on both fronts, it makes sense to pursue MMC. ‘Minimising waste and optimising the recycling of building materials are fundamental to reducing embodied carbon in construction,’ says Emma Swarbrick, associate at Jo Cowen Architects. ‘MMC, particularly offsite manufacturing of components, panels or volumes, can increase material efficiencies.’

Anxiety about climate change will also see many more ask for less carbon-intensive construction techniques, which is where CLT and timber star

MMC also tends to involve the use of renewable materials, which, combined with greater efficiency, can massively reduce embodied carbon. ‘Generally, MMC involves timber, which is low carbon,’ says Marie-Louise Schembri, project director at engineering consultancy Hilson Moran. However, the use of timber products can be an emotive topic. According to Steer, the recent blaze at Barking Riverside, where fire spread across wooden balconies, deepened public distrust of timber in the public’s eyes and will be hard to rectify.

‘It’s really difficult because the actual frames with products such as cross-laminated timber [CLT] are absolutely fine,’ he says.

‘There is this feeling in the public that wood can burn. It’s a perception that isn’t particularly right, but the Barking fire certainly will not have helped the image. It will have set the industry back by 15 years or more.

‘If you’re going to buy an apartment and they say it is all timber frame, you’ll probably walk down the road and buy one made out of brick.’

But David Birkbeck, chief executive of research and lobbying group Design For Homes, firmly disagrees. ‘Most CLT blocks are faced in brick and because internal CLT panels are so dense, few know it’s not concrete,’ he says. ‘Buyers will ask more about timber elements applied to elevations, but anxiety about climate change will also see many more ask for less carbon-intensive construction techniques, which is where CLT and timber star.’

And it does appear that the government’s support for MMC is linked to its rapidly evolving carbon-cutting commitments. In his Spring Statement, chancellor Philip Hammond pledged that a new Future Homes Standard would be introduced by 2025 to support the prime minister’s clean growth strategy.

‘MMC is a big part of supporting that,’ says Paul McGivern, MMC specialist at Homes England. ‘The detail of the Future Homes Standard isn’t available at the moment, but I suspect that carbon will form a key part. My understanding is that the standard will be incorporated within building regulations.’

Whether or not the government acts, Andrew Waugh, director at Waugh Thistleton Architects, is clear that architects have a duty to change their behaviour and start thinking deeply about embodied carbon and how MMC can help.

‘Architecture has not woken up to the sustainability benefits of MMC.’

Different types of MMC

Panelised

Panel units are produced off-site in factories. The panels generally consist of wall, floor and roof units and are put together on site to create a three-dimensional structure.

Closed panels

This involves installing lining materials and insulation in a factory environment. Panels can be produced using both carbon-intensive materials, such as steel and concrete, or renewables like wood.

Volumetric or modular construction

Unlike panels, volumetric construction involves the production of three-dimensional units in a factory environment. The units are then transported to site and assembled. The level of finish of units varies markedly.

Modular developer’s view on the housing crisis

Joseph Daniels, founder of Project Etopia

For all the talk about the government’s ambitious housing targets, there is still a lack of urgency, and this has meant starts on new homes are down 9 per cent on both the previous quarter and the same time last year.

Latest statistics effectively show house-building has swung into reverse yet again, and is a further sign that the industry is not consistent enough in its delivery of new homes. A slump in the pipeline of new homes is now programmed in for later this year.

With new build starts also 25 per cent down on the pre-crisis peak, the structural problems of the UK’s housing market and the industry’s timid reply are still painfully obvious, even after £10 billion of public money has been thrown at it in the form of the Help To Buy scheme. The UK needs a revolution in house-building, not a peaceful protest.

The rate of progress means government targets remain a pipedream, and the people it hurts are those desperate to get on the housing ladder, who are locked out by high prices because the supply is simply not there.

Housing is in a state of crisis, yet the response has not reflected how high a priority house-building needs to be.

Only by turning to modern methods of construction, which are much faster than traditional building, can we hope to deliver the housing the country desperately needs.

The Architects’ Journal Architecture News & Buildings

The Architects’ Journal Architecture News & Buildings

The modular future arrived decades ago. I was working in the sector as late as the 1990s. Just because ‘big business’ in London have only just discovered it doesn’t mean it didn’t exist before!

Montreal olympics Safdie