Last year, a Chinese scientist earned global condemnation for genetically editing two infant girls. Now a Russian molecular biologist named Denis Rebrikov wants to try it again.

Speaking to the scientific journal Nature, Rebrikov says he will use CRISPR techniques to target CCR5, which affects HIV, the same gene that He Jiankui focused on during his now-infamous efforts. He's work ostensibly wanted to make the children, now known as Lulu and Nana, HIV-resistant. Rebrikov's work looks like it will focus on the same challenge.

Russia has the largest HIV epidemic in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, according to advocacy group Avert. Unlike the majority of the world, AIDS is on the rise on Russia, with the rate of new infections rising between 10 and 15 percent annually.

A "continued shift away from progressive policies towards socially conservative legislation is a barrier to implementing HIV prevention and treatment," the group says. Michel Kazatchkine, a special adviser to UNAIDS in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, estimated last year that as many as 2 million people in Russia may be infected.

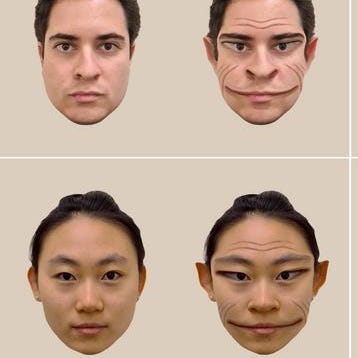

While He was able to successfully edit CCR5, his work failed to address the complexity of what's known as a genetic mosaic, where even the slightest changes can affect other aspects of the genetic code. His work may have shortened the children's lives and made them more vulnerable to other diseases like the West Nile virus.

There's a consensus in the scientific community that He's work violated nearly every one of its principles—both in thoroughness and in disclosure, considering how he misled the parents of the infants on what he was doing to their children and the risks involved. Rebrikov, who leads a genome-editing laboratory at Russia’s largest fertility clinic, tells Nature that he will be able to avoid He's mistakes.

Unlike He, Rebrikov will seek approval from three government agencies, including the Russian health ministry. Nature says that Rebrikov "plans to disable the gene, which encodes a protein that allows HIV to enter cells, in embryos that will be implanted into HIV-positive mothers, reducing the risk of them passing on the virus to the baby in utero."

That's radically different than He's work, which focused on embryos from HIV-positive fathers, which geneticists say has little effect on an embryo.

Rebrikov tells Nature he has already entered into an agreement with a clinic in Moscow to recruit women for his effort.

There are potential political challenges to working within the Russian system. The Russian Orthodox Church wields a large amount of power in modern Russia, with some commenters calling it an example of the country's "soft power," able to influence social norms within the country.

Official church doctrine says that "the aim of genetic interference ... should not be to improve artificially the human race or to interfere in God’s design for humanity," which would seemingly rule out Rebrikov's experiments.

But even if Rebrikov can navigate around the church, scientists around the world are not convinced.

“The technology is not ready,” Jennifer Doudna, a University of California Berkeley molecular biologist who helped create the CRISPR-Cas9 genome-editing system that Rebrikov plans to use, tells Nature. “It is not surprising, but it is very disappointing and unsettling.”

Whatever improvements Rebrikov has made on He's system, scientists still see the same fundamental problems: CRISPR could cause unintended ‘off-target’ mutations away from the target gene, like He's work. “The data I have seen say it’s not that easy to control the way the DNA repair works,” Doudna tells Nature.

While there is an urgent need for medical intervention in the Russian AIDS crisis, scientists are unconvinced that such a risky procedure could become anything more than a stunt.

“We know a lot about its [CCR5’s] role in HIV entry [to cells], but we don't know much about its other effects,” says Gaetan Burgio at the Australian National University in Canberra, a geneticist who studies CRISPR.

There are safer, proven ways to prevent HIV, scientists say. Among them is pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), a course of drugs proven to reduce a person's chances of contracting HIV. Russia does not currently offer PrEP drugs, although last year the country's AIDS Center Foundation announced a trial run. Proven harm reduction policies, like needle and syringe exchange programs, have come under attack from the government in recent years.

In an editorial separate from its reporting on Rebrikov, Nature is critical of his project. Founded in 1869, Nature is commonly seen as being among the most influential scientific journals in the world, with the highest so-called impact factor of any journal.

"The scientific community now has an opportunity to do what they couldn’t with He — work with Rebrikov to identify and discuss the risks," the journal's editors say. "That’s better done by engaging with him than by branding him a maverick. And Rebrikov must listen to the concerns and the critics, and not move forward until the dangers are assessed.

Time is of the essence. The committee advising the World Health Organization (WHO) is not likely to issue its final recommendations on an international framework to govern the use of human-gene-editing technologies before 2020. Rebrikov says he might start his experiments this year; perhaps elsewhere, plans are already further ahead.

Plenty has been said about the need for debate, consensus and regulation on human germline gene editing, but that process has to keep up with the speed at which researchers can actually do the work.

Source: Nature

David Grossman is a staff writer for PopularMechanics.com. He's previously written for The Verge, Rolling Stone, The New Republic and several other publications. He's based out of Brooklyn.