The day my Chinese dad was declared a ‘bona fide’ Indonesian and given a new name

Stanley Widianto is too young to recall the last time Indonesians turned on their Chinese neighbours, but seeing Jakarta’s Chinese Indonesian governor jailed by a court this year was a jolting reminder of the official prejudice his own father had to overcome

When Jakarta governor Anies Baswedan used the word pribumi in his inaugural address on October 16, it left the people he will serve for the next five years divided. He had just been elected in a race for governor against Chinese Christian incumbent Basuki “Ahok” Purnama, who had earlier been sentenced to imprisonment by the North Jakarta District Court.

The opposition camp criticised Anies for his use of the discriminatory word – which translates to “indigenous Indonesians” and implies that Chinese Indonesians are not natives. His followers defended him, claiming the country had moved on and the word was no longer offensive.

The Chinese Indonesians with long memories and escape plans in case racial violence flares again – despite signs of tensions easing

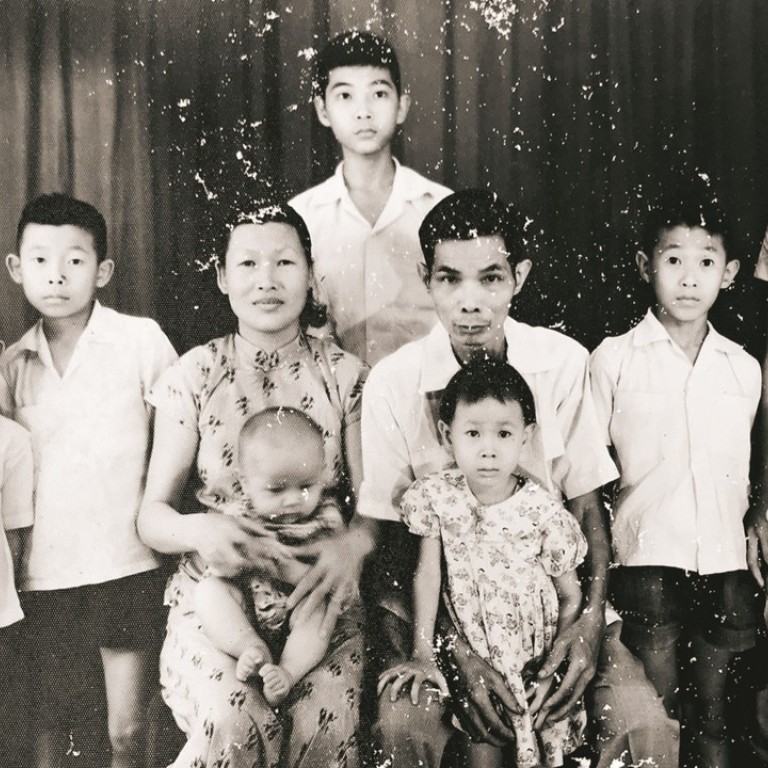

It reminded me of another Chinese Indonesian who went to court in November 1984, and that was my father.

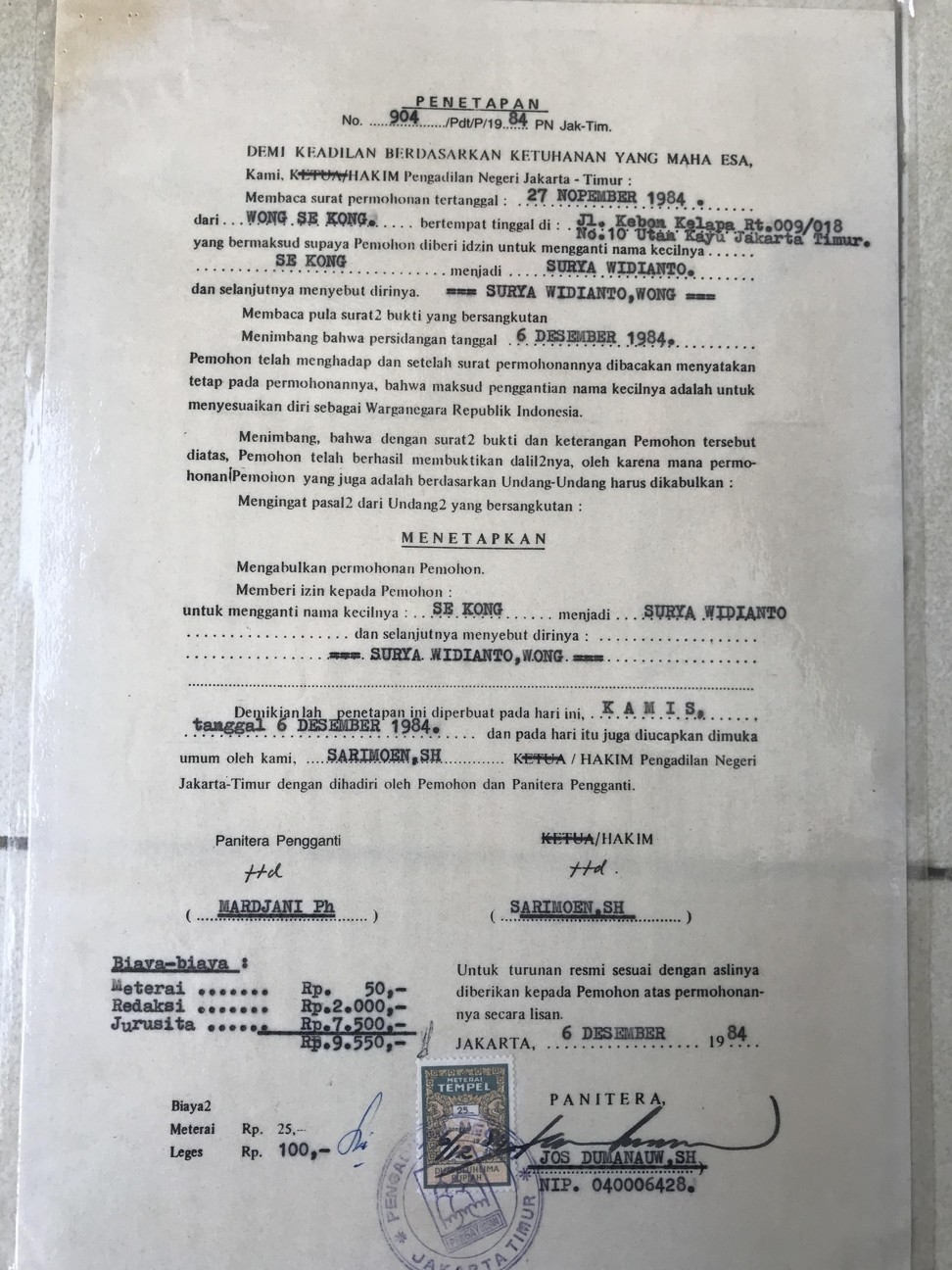

At a courthouse in East Jakarta, the then 23-year old Wong Se Kong presented himself with all the necessary documents and paid the fees required to reject his former alien status and become a “bona fide” Indonesian. If he had not, he would not have been permitted to graduate from the college he was attending.

Regarding it as just another bureaucratic hurdle, he fixed the “problem”. Thereafter he had a new name, which would appear on his ID card, marriage certificate, and the birth certificates of his three children: Surya Widianto Wong.

My father, now 56, says he chose the name because he just liked the way it sounded, but he can’t remember how he felt that day. I couldn’t imagine what it must have been like living with the continuous, forced assimilation policies in the era of former president Suharto, whose ‘New Order’ regime (1967-1998) enacted laws to counter the “Chinese problem”.

Chinese-language newspapers were shut down. Festivals and cultural activities, such as lion dances, were forbidden. Chinese political parties were disbanded and schools abolished. The government discouraged teaching of all Chinese dialects, including my grandparents’ native Hakka.

The discrimination was essentially a continuation of the Dutch policy of passenstelsel – in which Chinese Indonesians were required to carry a pass to travel outside their city of residence.

In the eyes of Suharto’s military-backed regime, we were “Cina”, (the Indonesian word for China, but also a chilling racial epithet). We were the unpatriotic “rats”, the “rich pariahs” with big houses and even higher fences.

In 1966, the government decreed that Chinese who failed to adopt Indonesian names would face penalties, such as exorbitant passport fees. A law requiring them to present a letter proving their citizenship went into effect from 1978 to 2006.

But the Chinese had something to offer the country that gave them leverage – their inherent business acumen. In the Dutch colonial era – from 1603 to 1800 – the Chinese were categorised as second-class “foreign orientals” through the Indische Staatsregeling law. They were given the task of collecting taxes from the “third-class” pribumi, or native Indonesians, for the Dutch government.

Suspected Indonesian radicals armed with bows and arrows burn down police complex

The regime of Suharto also recognised the business nous of the Chinese and capitalised on Chinese company owners – referred to disparagingly as cukongs, or taipans – by giving them government contracts and investment credit in exchange for, among other things, campaign funds.

The arrangements only exacerbated the rift, however, and fuelled the perception that the country’s ethnic Chinese – estimated at one per cent to four per cent of the population – controlled the economy.

I was less than two months old when the deadly riots of May 1998 broke out. The violence in cities across Indonesia was a response to years of economic anxiety and political uncertainty surrounding Suharto’s long-awaited downfall. Though not the only casualties, many Chinese businessmen were shot and hundreds of ordinary Chinese Indonesians were raped or murdered.

Christine S. Tjhin, a researcher on Sino-Indonesian relations at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies, recalls how her Jakarta home was attacked and she was saved by local Muslims.

“It took me more than three months to settle down from my trauma, which is when I decided to go out of the house again. It took me almost a year to try to trust [the] pribumi again,” she says.

There have since been attempts by successive government to deal with racially discriminatory laws. In 2001, then president Abdurrahman Wahid lifted the ban on celebrations for the Lunar New Year. The following year, his successor, Megawati Sukarnoputri, declared it a national holiday.

Although Cina, often used as an insult, is still heard on the streets of Jakarta, the racial epithet was finally erased from all constitutional documents in 2014. Political participation among ethnic Chinese citizens has been on the rise since then, and more Chinese Indonesians have joined presidential cabinets.

It took me more than three months to settle down from my trauma, which is when I decided to go out of the house again

But the “sins” of our past have merely slept. I’ve seen them in my resolve not to learn the Chinese language. I joke that I’m only Chinese once a year: when I’m given lai see – red packets containing “lucky money” – by family members during the Lunar New Year.

I see them in my given name and my father’s chosen name. And I saw them again when another Chinese Indonesian went to court this spring.

Purnama – known among Chinese Indonesians as Ahok – had served as Jakarta governor since 2014 and was voted in as vice-governor to now-President Joko Widodo in 2012. Purnama made a name for himself through clean governance at best, and profanity-laced tirades at worst.

But to the large crowds who began taking to the streets of Jakarta at the end of last year, howling for his imprisonment, Purnama had unforgivably sullied the name of Islam. A video of a speech in which he used a Koranic verse to question people who doubted his leadership simply because he was a Christian went viral on the web. He was sentenced in May to two years in prison after a lengthy trial for violating Indonesia’s blasphemy laws. His repeated apologies made no difference.

Tjhin argues Purnama’s election loss, and the vitriol directed at him, stemmed partly from his use of security forces to carry out mass evictions of illegal squatters, and an election campaign that focused more on appealing to emotions than his track record.

THE PLIGHT OF CHINESE INDONESIANS: DISTRUSTED IN JAKARTA, FORGOTTEN IN CHINA

In an interview days after Purnama’s sentencing, Salafist intellectual Bachtiar Nasir, while promoting affirmative action for the pribumi to counter economic disparity, said, “it seems [Chinese Indonesians] have not become more generous, more fair”. He then warned: “The state should ensure that it does not sell Indonesia to foreigners, especially China.”

“The truth is, anti-Purnama sentiments were used as a conduit through which people spouted their racial presumptions,” says Bonnie Triyana, a historian and the editor in chief of the magazine Historia.

The image of Chinese wealth looms large in the archipelago, as does racial discrimination. President Widodo was falsely accused of being of Chinese descent during his presidential campaign in 2014. The Islamic student organisation Kammi accused his administration of succumbing to China in 2015. Last year an ordinary Chinese Indonesian man, Andrew Budikusuma, was called “Ahok” and beaten up at a Jakarta bus stop.

It’s difficult to know whether the fall of Purnama and the ratcheting up of anti-Chinese sentiment was a result of his image as the “clean politics guy”, having sacked incompetent officials. Hardliners such as the Islamic Defenders Front may well have singled him out for their own political gains.

Researchers Aaron Connelly and Matthew Busch note in an analysis published by the Lowy Institute: “Without a target as prominent and polarising as Purnama, it will be more difficult to use anti-Chinese populism to mobilise popular resentment to the same degree.”

In his seemingly prophetic non-fiction work, Hoakiau di Indonesia, late Javanese writer Pramoedya Ananta Toer described Chinese Indonesians as the “foreign non-foreigners”. Sentiments towards them, he wrote, were “systematically engineered by those in power” to profit for themselves.

Indonesia detains top corruption suspect Novanto after he claimed injury in car crash

Toer wrote those words in 1960. More than five decades later, the imprisonment of Purnama brings reminders of pain, division and difference. Whatever it means to the future of Indonesia, when a Chinese Indonesian goes to court, it still has to mean something.

Stanley Widianto is a Jakarta-based writer