One of the features of being a parent of more than one child is that you can view the curriculum of an older child through the eyes of a younger one. On the basis of my observations, can I share with you my impressions of what’s happening in secondary education?

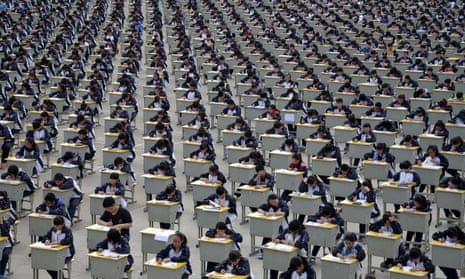

The story starts with Pisa-envy: the misplaced view that the international Pisa tables represent a useful and valid way to compare education systems, and that politicians should command a country to fit the Pisa worldview.

We’ve seen ministers slaver over Chinese Pisa results as if these were a true representation of the full range of Chinese schools, rather than a highly selective one. Then, ignoring the fact that an education system will always reflect and help construct society as a whole, ministers talk as if they want to bolt the Chinese way on to our system. Have they suddenly become fans of Chinese Communism? Are they just using Pisa as a way of peddling their own highly hierarchical views of what education here should be, or do they really believe that the failings of British capitalism depend on the school curriculum rather than decades of chronic underinvestment?

It was this atmosphere that led us to the “knowledge-rich curriculum”, the move to stuff syllabuses with more facts. The principle here is that knowing more facts makes you cleverer. This is a debate about whether children can think conceptually with a few rather than many facts, and indeed whether a fact-rich education will enable children to think conceptually later on. What this debate doesn’t handle is what happens to the children for whom the new curriculum is too much and too difficult.

The obsessive-compulsive behaviour around the new grading system for GCSEs (using numbers rather than letters) does little more than distinguish the highest fliers from the high flyers. Is there a social need for this? Do the great problems of today’s society – poverty, inequality and personal debt – cry out for a reform that distinguishes tiny percentage differences between top-performing pupils, while hundreds of thousands of students below the line are treated as collateral damage?

All this is directly affecting teachers, children and parents. Statistics can’t express the boredom and stress produced by a curriculum that is pushing the GCSE syllabus down from years 10 and 11 into years 7 and 8. Older siblings look at what younger children are struggling with and say: “We didn’t do that till year 10.”

The notion of attainment has become entangled with time, as if doing well at school must mean doing well early and quickly. What’s the hurry? Which bit of education theory tells us that every child benefits from the educational equivalent of panic-buying? A minority do, of course, but for the others, what are the side-effects of the humiliation of years of feeling “I can’t learn all this”?

This question is hard to answer because of both the told and untold statistics on exclusion. We know exclusions are going up, but anyone working in schools hears over and over again stories of covert selection or “dumping”: schools quietly losing pupils from individual exams or altogether, so their league table position is not threatened by too many “fails”.

Let’s say it clearly: thousands of secondary pupils are being junked and a good deal of it is invisible. More collateral damage.

Occasionally, people in your position have made political hay by saying that they were interested in the “attainment gap”. Scenarios have been painted of hordes of illiterate children turning into drug addicts and criminals unless a new government came in and kicked teachers and pupils up the backside. This is not the message of the moment, though, is it?

Exclusion means selection and when you knit that in with the steady creep towards selective admission into secondary schools, you have a built-in disregard for the attainment gap. Rather, it cements it and honours it. Should you or anyone in your team resurrect concern for this gap I, for one, would point the finger at the raft of overt and covert methods at work that create the gap through the school system itself.

I’m worried. Are you?

Yours, Michael Rosen