'You Just Can't Shake It'

For the first time, Seahawks running back Eddie Lacy opens up about his agonizingly public struggle with weight.

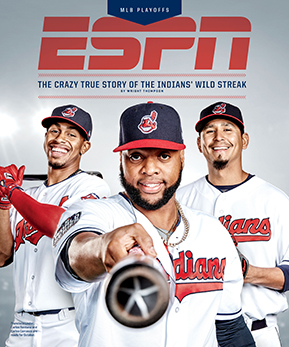

This story appears in ESPN The Magazine's Oct. 2 MLB Playoffs issue. Subscribe today!

It's 75 degrees and beautiful in Renton, Washington. The sky is clear and blue. When new Seahawks running back Eddie Lacy climbs out of his Corvette and waves to me in a park near his condo, I notice he's brought a towel. It's a small towel, tan and about the size of a dishrag. We find an empty bench, near the playground, and take a seat. As Lacy speaks in an affable baritone, he holds the towel gently in his thick hands, occasionally massaging it like he wants assurance it's still there.

Eventually he explains that he gets nervous when he does interviews, and he sweats when he gets nervous. So he came prepared today.

Lacy had to think long and hard before agreeing to meet up and talk like this. There is a good chance, each of us concedes, that this interview will just give his trolls a fresh batch of ammunition. Social media has done wonders in recent years to bridge the gap between fans and professional athletes, but increased intimacy comes with drawbacks, and nobody understands that better than Eddie Lacy.

"I could pull up my Twitter right now and there would be a fat comment in there somewhere," he says. "Like I could tweet, 'Today is a beautiful day!' and someone would be like, 'Oh yeah? You fat.' I sit there and wonder: 'What do you get out of that?'"

When the internet turns one of your most personal flaws into a meme, how the hell do you possibly escape it?

Ever since his weight became a public topic during his four years in Green Bay -- which included two 1,100-yard seasons -- Lacy had read those kinds of comments and brooded in silence, convinced he couldn't win. Responding would only give his tormentors a smirk of satisfaction, knowing they'd wounded him. If he worked hard, got back in shape through yoga and P90X, maybe then the jokes would fade.

Except they didn't fade. If anything, they multiplied.

And while he lost weight -- albeit slowly -- getting down to where he wanted (around 240 pounds on his 5-foot-11 frame) and keeping it off was a miserable slog during his Packers years. In the meantime, people photoshopped pictures of Lacy's stomach to make it seem like he had a Santa Claus physique. Someone searched through his Twitter account and noticed that back in college he had an affinity for Chinese food, and he loved tweeting about it. They screenshotted every tweet and made a collage that quickly went viral.

"I always called it China food," Lacy, 27, says with a grin. "There is no way around it, I love sesame chicken and shrimp fried rice so much. It's awesome."

He chuckled at first, but the collage also stung. It kept showing up in his feed, an endless cycle of snark, rebooted each day. "It sucks," Lacy says. "It definitely sent me into a funk. I wish I could understand what they get out of it."

When Lacy left the Packers in free agency and signed with Seattle, agreeing to periodic weigh-ins as part of a one-year contract laden with incentives, his fight to shed the pounds he'd put on after ankle surgery became something of a recurring national joke. He stood to make $55,000 every time he hit a weight goal, but at some point he started to feel indifferent about the money. Instead, the monthly ritual of turning his weight into a public spectacle began to feel a bit like a public shaming.

He assumed the weigh-ins would stay private, between the team doctors and Seahawks coaches. But the first time he weighed in, he remembers the result getting out within 20 minutes. Even his agency tweeted it out when he passed the first two weigh-ins, despite the fact that its client was hardly thrilled to share the news.

"I hate that it has to be public," Lacy says. "Because it's like, if you don't make it, what happens? Clearly you don't get the money, but whatever. I don't really care about that. It's just more the negative things that are going to come."

It's uncomfortable for Lacy to delve into all this, to put his struggle into any kind of context that feels relatable. In part, that's because he stopped opening up to people when he was in high school, shortly after Hurricane Katrina destroyed his house in Gretna, Louisiana, upending his family's life and leaving him with no emotional anchor, no real place to call home. It took years for him to sort through the impact of that upheaval. The recent hurricane disaster scenes opened up some of those old wounds.

"It pretty much brought back everything that happened to me," Lacy says of Hurricane Harvey. "Nobody's life will ever be the same there. It just sucks."

He agreed to chat, however, in part because he knows he's talking to a kindred spirit. We've both stared in misery at a chicken breast and a salad, reluctantly fighting off the urge to add french fries. We've both learned to dread looking down between our toes and seeing the cold, hard numbers stare back from the scale, almost taunting us. We're both around 6 feet, 245 pounds, and don't look fat per se, but we sure as hell ain't skinny. Guys like us don't garner much sympathy. There's no backlash when we're the butt of sitcom jokes. It's easy to look at us and assume a lack of willpower, a weakness in our character. And in our darker moments, we can't help but wonder: "Are those people right?"

The difference between us, though, is that I wrestle with my fried-food demons mostly in private. Lacy is bombarded with insults every time he opens an app on his phone.

"You just can't shake it," he says. "And no matter what, you can't say nothing back to them. You just have to read it, get mad or however it makes you feel, and move on. I could be 225 and they'd still be like, 'You're still a fat piece of s---.'"

In September 2015, Lacy's electric first two seasons in Green Bay had him ranked near the top of most fantasy draft boards. Dennis Wierzbicki/USA TODAY Sports

Lacy was never lazy as a kid growing up in the New Orleans suburb of Gretna. He was always moving, always on his bike zooming around the neighborhood. He wouldn't even sit still long enough to watch sports on TV. He got bored. He preferred to be out in the yard playing sports. He and his friends did everything -- football, basketball, baseball. (One of Lacy's closest childhood friends, Joe Broussard, is a Triple-A pitching prospect for the Dodgers.) "I used to be small and skinny, and I had braids like Allen Iverson," Lacy says. "I really thought I was going to be like AI."

After school, he and his brothers would race home, watch 30 minutes of cartoons -- Dragon Ball Z was his favorite by far -- then play outside until the streetlights came on and their parents ordered them inside. According to his mom, Wanda, Lacy was one of the happiest, most outgoing kids in the neighborhood.

"He was always such a playful kid," Wanda says. "His teachers would tell me, 'Eddie does his work, but as soon as he's done, he's distracting the class.' He loved to make people laugh. He was always a little jokester."

Everything changed, though, at the start of Lacy's freshman year of high school in 2005. With Katrina looming, the Lacys escaped to Beaumont, Texas, to stay with family, leaving behind their three-bedroom brick house in Gretna. They watched the news footage from afar, wondering when -- then if -- they'd return. It would be weeks before that was possible, and when they did come back to collect what was left, they wore masks because the stench was so strong. Their home was destroyed, most of their stuff looted. They stayed in Texas until the money ran out, then moved in with Lacy's aunt in Baton Rouge for a spell. Ten people shared a house with three bedrooms and one bathroom. Eventually, they moved into a tiny trailer in Geismar, a small town 30 minutes south of Baton Rouge. "I honestly just shut down," Lacy says.

Wanda and her husband, Eddie Lacy Sr., knew their son was hurting, that he wasn't making friends and was angry at the world, but there wasn't much they could do. The whole family was just trying to survive. The football field became an outlet for Lacy. He ran with anger, unleashing his frustration on poor defenders, eventually earning a scholarship to Alabama.

Wanda was a big believer in therapy, but Lacy didn't want to talk to anyone. So she asked him one day if he'd at least be willing to scribble down his feelings and frustrations in a journal as a form of release. He agreed, but he also had a request.

The ceiling of Lacy's childhood bedroom had been covered with glow-in-the-dark stars. Every night, he lay awake in the trailer, staring at the dark ceiling, missing his old bedroom. Was there any way, he asked, she could find more of those stickers? It took Wanda several weeks, but eventually she spotted some in a Winn-Dixie in Baton Rouge. While he was at school, she covered his ceiling and walls with them. Lacy was so happy, the happiest he'd been in months, maybe years. "I look up and I feel like I'm in the sky," Lacy told his mom. "Everything seems OK when I'm looking up."

If there was one other thing that made him feel safe and back to normal, it was gathering with his family for home-cooked meals. Even though his mom was going to nursing school up in Baton Rouge, she made it home every day to prepare dinner.

"It was southern Louisiana cooking, so nothing healthy," Lacy says. "No vegetables to speak of, I'll tell you that. Typical dinner might be fried chicken, red beans and rice. Or pork and beans. Fried pork chops. Everything that is not good for you that tastes good, you know? Crawfish too. That was probably my favorite. I could eat crawfish literally every day."

Looking back, he can't help but wonder whether his eating habits might have been different if he'd grown up someplace where healthy eating is more widely emphasized. But his family was in the same classic trap as so many families struggling to feed a big group on a small budget.

"It was all bad stuff, but it was cheaper, so we didn't have to spend a lot of money on it," Lacy says. "Even if we had gone the healthy route, how long could we have sustained it? Maybe a couple weeks, or maybe a month. Everything we ate, my mom made us eat bread with it because she knew it would fill us up and we would feel less hungry later. She had to feed us, and she did the best she could."

"You just can't shake it," Lacy says. "And no matter what, you can't say nothing back to them. You just have to read it, get mad or however it makes you feel, and move on. I could be 225 and they'd still be like, 'You're still a fat piece of s---.'" Ian Allen for ESPN

When Lacy arrived at the University of Alabama in 2009, it was the first time since Katrina that he felt comfortable in his surroundings. He made friends, and he was thrilled to get out of that trailer. But on the field, he was overwhelmed. Defensive linemen were faster than he was, and he'd never lifted weights, just getting by on his natural strength and talent. Now the Crimson Tide coaching staff was pushing him to exhaustion. He second-guessed his decision to come to Tuscaloosa nearly every day.

"It was the worst year of my life," Lacy says. "But it just shows if you push your body, it responds. For four years, you have somebody telling you what to do, make you as big as you can, as strong as you can, as fast as you can be. They try to make this bionic person, basically. But it just shows if you push your body, it responds."

Once he made it to the NFL -- drafted in the second round by the Packers after running for 1,322 yards and 17 touchdowns as a junior, capped by winning Offensive MVP honors in Bama's BCS championship victory over Notre Dame in January 2013 -- Lacy could hardly believe how easy practices were. After his first Packers workout was over, he thought to himself: "This is all we have to do?"

Looking back, he concedes he could have done a better job of pushing to stay closer to his ideal weight. But at the same time, he was succeeding. He was the NFL offensive rookie of the year in 2013. He ran for a combined 2,317 yards his first two seasons, rolling downfield like a bowling ball but with the feet of a dancer. To watch him lower his shoulder into a defender, then pirouette into a balletic spin move, was like seeing a work of football art. At times, he looked like a reincarnation of Jerome Bettis, the Steelers running back who rumbled into the Hall of Fame.

The Packers, though, didn't see it that way. They were initially supportive of Lacy's fight to keep his weight down, but their patience eroded. When Lacy's production dipped in his third year, coach Mike McCarthy made it clear in a season-ending news conference that Lacy could either lose weight or lose playing time. "He's got a lot of work to do," McCarthy said. "His offseason last year was not good enough, and he never recovered from it. He cannot play at the weight he played at this year."

The two cleared the air in private, with McCarthy expressing regret for calling his running back out in a news conference, and Lacy insists now that no hard feelings lingered. He says he was ultimately motivated by the whole thing.

But the fat jokes mushroomed. No one saw him as a charming-if-chubby wrecking ball like Bettis. "I don't get it," Lacy says. "[Bettis] is a Hall of Famer. I guess times are just different. They really don't have big backs anymore."

Lacy showed up for the 2016 season in excellent shape, having dropped 22 pounds in the offseason by doing P90X workouts, and he declared he was done talking about his weight. There were no complaints about his play either, as he averaged 5.1 yards a carry through five games. But when an ankle injury in October led to season-ending surgery, all his hard work was quietly erased.

"I literally couldn't do anything for months," Lacy says. "I obviously just got bigger. I can't do nothing about it. All you can do is lay down and eat. What are you supposed to do?"

He decided a change of scenery might be good for everyone and told the Packers he'd explore free agency after the season. When he began visiting teams and a few of them asked him to step on a scale, even Lacy was a bit surprised at what he saw: He weighed 267.

"Sometimes I wish I was a person with high metabolism who could just eat whatever they want and can't gain a pound," Lacy says. "You've got certain teammates who are like, 'Man, it don't matter what I eat, I can't gain weight.' And I'm like, 'It don't matter what kind of diet I'm on, it's super hard for me to lose weight, and it's so easy for me to put it back on.'"

Lacy's new contract (one year, $5.6 million) includes a $55,000 bonus every time he makes a monthly weight target. Joe Nicholson/USA TODAY Sports

Should you feel sympathy for Lacy, or skepticism and scorn?

On one hand, a professional athlete's body is the engine that drives his economic value. If you can't maintain that engine, it doesn't make you a bad person -- more than a third of Americans are overweight -- but professional sports will be a challenge. Most of us don't follow sports to see people we can relate to. We expect peak physical excellence. There have been exceptions -- golfer John Daly comes to mind -- but very few. Even Babe Ruth was frequently ridiculed for being out of shape.

On the other hand, it's not like Lacy isn't trying. He's lost more than 20 pounds since signing with the Seahawks. He doesn't see how weighing less will make him more effective, and 245 is as low as he needs to be, according to his contract.

Still, during every team dinner, Lacy dutifully grabs a grilled chicken breast and a salad and tries to ignore his teammates as they pile chicken wings and spaghetti and ice cream onto their plates. Lacy says he hasn't had Chinese food in "forever," so long ago he can't even remember. Yet every single day this offseason, someone was happy to remind him of that old life, the days when he could eat whatever he wanted.

"People are always tweeting at me stuff like: 'I'm about to go get China food, shout out to Eddie,'" Lacy says. "Or, 'Hey, Eddie, this China food is why you weigh 260 pounds.' You want to say, 'Dawg, that was five years ago. How is something that happened [then] still relevant?' But nobody cares. The negativity is always there, whether you're doing good or you're going through a funk."

“I sit there and wonder: 'What do you get out of that?'”

- Lacy on the constant weight comments he receivesIn this era of social media, once you become a meme, it doesn't really go away. The internet never forgets. Lacy is mostly at peace with that. He posted his Beachbody workouts on Twitter and Instagram this past offseason, knowing he'd be mocked. (He was.) He does find snippets of encouragement in the handful of positive comments: "Every one of those gave me a little more courage," Lacy says.

Even after a promising preseason, the trolls returned en masse on his Instagram after a disappointing performance (five carries for just 3 yards) against his former team in Seattle's first game: Eddie Lacy needs to go vegan like yesterday! Maybe you shoulda put the Eddie Burgers from A&W down and you'd still be on the Packers' roster. And they swarmed on Twitter after he was a healthy scratch in Week 2: Eddie Lacy getting millions to be a lazy fat f---.

If he's being honest, though, there is a part of him that kind of likes being big.

Sometimes Lacy likes to imagine there is a kid out there following his career, maybe someone who is a little thick around the waist and not blessed with great metabolism but who has quick feet and great balance. Someone wants to make that kid a lineman, but he wants to stay at running back. Maybe he lives in a trailer, feeling lost and displaced, but he stares up at the stars on his ceiling at night, dreaming of the unlikely but not impossible.