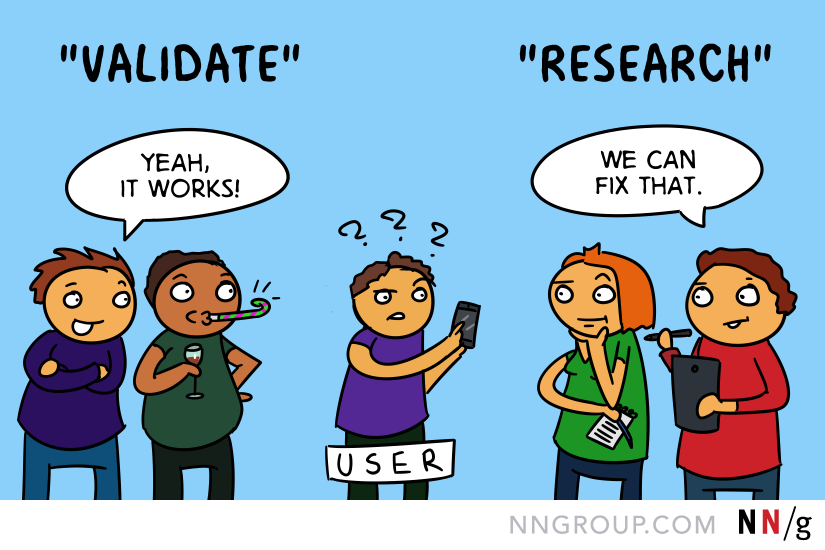

All too often people use the word "validate" to justify their UX work. As in, "Let's test the design to validate it," or “Let’s do an expert design review to validate this iteration.”

I strongly oppose using "validate" in this context. Call it a pet peeve. Call it semantics. Call me rigid. But let me tell you why I feel this way.

User research is as much a mindset as it is a science and an art. In a user study, attitude greatly affects participants, your team’s reactions to their behaviors, and follow-up actions on study findings. Planning the testing, observing users, analyzing findings, and describing the research process all require a delicate balance of curiosity, realism, diplomacy, honesty, and a profound ability to welcome and withstand criticism.

The Effect on the Test Participant

What you say from the inception of the study to its conclusion — how you recruit, write tasks, ask questions during a test, and lead posttest interviews — can all subtly (or not so subtly) affect how the test participant reacts. It’s a simple matter of priming.

For example, imagine that, as you are briefing the test participant just before you begin a usability test, you say, "We would like to watch how you do things so we can validate the design."

This statement implies to users that they are not supposed to point out problems with the design. It also suggests that, if they don't understand something, they are inept because this design is finished and just in the phase of being validated, not in the stage when making changes would be expected and acceptable.

The Effect on Your Team

Saying to your team that you want to validate a design suggests that you know it works and are simply looking for concrete proof. It implies that you are resistant to learning that the design doesn’t work or that you may need to fix it in major ways. And when the team is thus biased, it can reason away major design issues as minor bumps, because the unsaid implication of “validate” is that the design is at a final stage.

When both the team and the study participants are thus primed by the word “validate,” user research turns into a complete waste of time and money.

User Research Should Uncover Many Negatives and Some Positives

A usability test should always find both positive findings and a substantial set of problems.

It is important to find and discuss good things about any design because:

- They help the team realize which design aspects work, so they don’t change them. (The old saying, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” requires you to know what’s good in the UI.)

- The team can learn about what makes a design good and may even be able to reproduce those positive traits in future designs by constructing design patterns and usability guidelines on top of instances of good usability.

- They can boost the team's morale.

- They solidify your credibility as a researcher. If you are always look at the negative, your perspective can seem imbalanced and not valuable.

The negative findings in a user study are obviously what drives design change and improvement. Any study should find some issues with the design. If it doesn’t, here are some probable reasons:

- The test was not set up well, and it would behoove you to look at your methodology to see if you structured your study appropriately. Jakob Nielsen has said many times, “If a usability study found nothing to improve in a design then that only proved one thing: that the test was done wrong.”

- The scope of your study was tiny. For example, you tested whether people notice a cursor change. In a case like that, the hypothesis is so confined that the study could, indeed, yield no negative findings — people did notice the cursor change and that was that. Studies like this happen a lot in inexpensive remote sessions. But efficiency dictates that an in-person study looks at more design aspects to offset its cost.

- Your team is inexperienced at analyzing user behavior. Maybe problems did occur in the test, but the team ignored them or did not know how to analyze them and thus found no issues.

- The team’s eyes are closed to negative findings. Because the stage was set before the test that the design is almost complete, the team did not notice usability issues, or the team members were afraid to bring them up.

In short, if your user study did not find any issues, something is wrong with your study or with your team. The perfect user interface has not been seen yet, and it’s unlikely to make its first appearance in world history during your current project.

If you are going to take on the cost of collecting and analyzing user data, you should also plan to support the cost of changing the design based on the study findings. Many teams don't plan for that last step, but they should.

Denying Issues Is Not the Same as Deferring Issues

Of course, sometimes a tight schedule or limited resources make it impossible to implement all the design changes suggested by the user study. But this reality doesn’t grant us license to say that there were no problems found in the study. There is a big difference between deferring design issues and denying their existence. It's better to discuss the problems found, rate their severity, and triage what can be done now. Even with a tight schedule, you may be able to try some of the following actions:

- Tweak the design slightly.

- Edit documentation.

- Tailor training.

- Forewarn support teams about usability issues expected to come up.

- Set analytics metrics to check the anticipated problems.

In the spirit of continuous quality improvement, consider your new release to be a prototype of the release to follow. By documenting known weaknesses in the new release, you have a leg up on the work of designing its replacement. Record these issues (in a database) and feed them into the requirements for the next release of this design.

Instead of “Validate”

What should we say instead of "validate"?

Try these:

- “Test”

- “Research”

- “Examine”

- “Study”

- “Analyze”

- “Watch how people use”

- “See where the design is successful and unsuccessful”

If “validate” is a permanent fixture for you or your team, consider balancing the possible priming by pairing it with “invalidate,” as in “Let’s test the design to validate or invalidate it.”

Conclusion

A sentiment better than “Let’s validate this design,” is ”Let’s learn what works and what doesn’t work well for users and why.”

Strictly banning the word "validate" from user research is an inflexible and rudimentary solution to a simplified problem. The greater point of focus is that subtle words inspire meaningful attitudes. These attitudes result in positive or negative actions and habits. A viable UX research program in the short and long term means: 1) making a habit of changing designs based on user feedback, and 2) using concise, descriptive, and constructive words when discussing research.

(Remember: user research can be cheap and fast: learn how in our full-day Usability Testing course.)