This year marks 60 years of the British Safety Council. SHP’s editor James Evison talked to historian Mike Esbester, the author of a commemorative picture book celebrating the organisation.

This year marks 60 years of the British Safety Council. SHP’s editor James Evison talked to historian Mike Esbester, the author of a commemorative picture book celebrating the organisation.

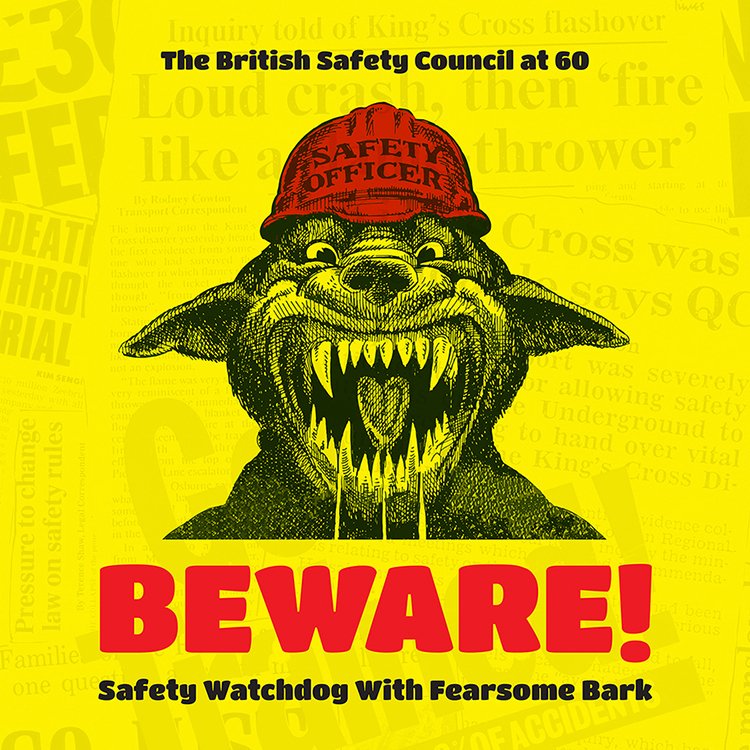

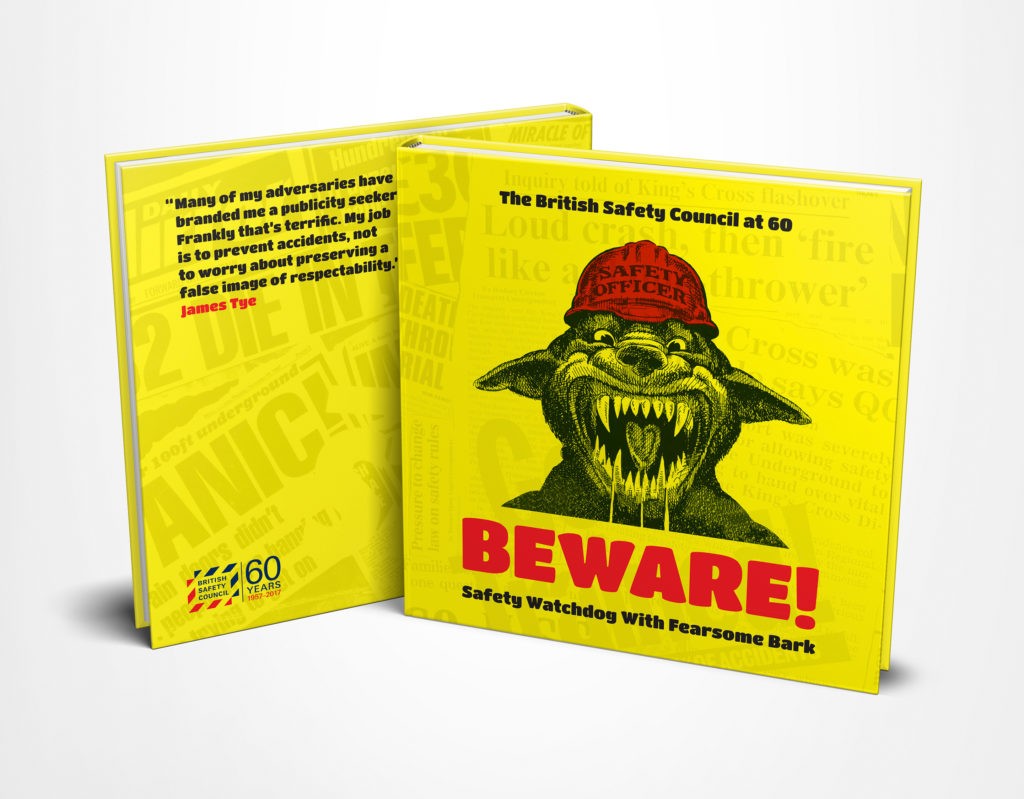

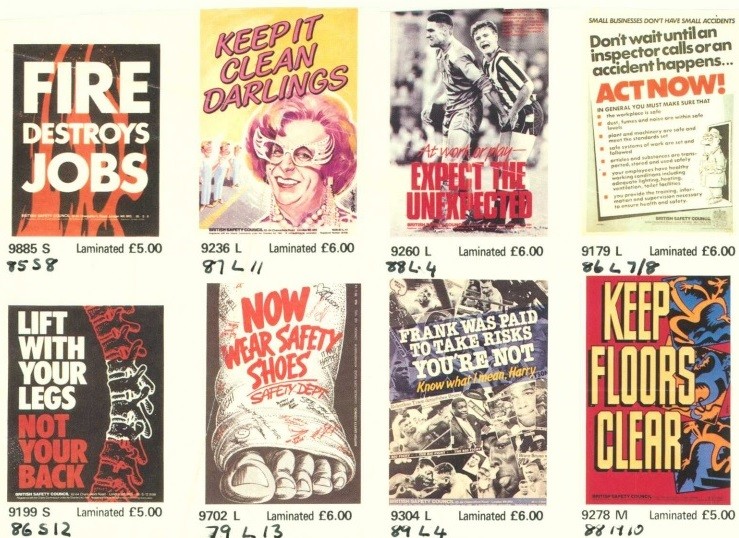

A quick look inside Dr Mike Esbester‘s and the Council’s ‘Beware! Safety watchdog with fearsome bark’ is not really possible. You are drawn in by the front of the book alone. It is a fantastically garish yellow, coffee-table sized hardback. The cover star is a cartoon dog – fangs out, dripping with spit, red ‘safety officer’ hat atop its head.

Standard practitioner guidance, this is not.

Esbester must be proud of the book. It is clearly a labour of love for both himself and the Council. Indeed, the journey from curation to creation to publication was littered with numerous interesting obstacles. It illustrated the commitment of the Council to making the book happen. And also Esbester’s skills as a historian and composer of the organisation’s narrative journey.

The beginning

The fact the book even exists is itself a testament to the oddities of institutional archiving, and the legacy of decisions made decades ago.

Esbester explained: “It started a long time ago, and took quite a while to come together. It really came to fruition through my interest in health, safety and risk.

“I had some Arts and Humanities Research Council funding and spent 9 months having a look at accidents and prevention in the 20th century. This got me in contact with the Council and Neal Stone (the Council’s former policy director). He said that the Council didn’t have anything in the archive.”

When asked why they didn’t have anything, Esbester’s response was stark: “Neal said the Council had binned it.”

Esbester then continued his research, including a monumental 258 page study with Professor Paul Almond for IOSH that looked at the “‘elf and safety gone mad” culture, The changing legitimacy of health and safety at work, 1960–2015.

Raiders of the lost (Mansfield) ark

During this time, he maintained contact with the Council, and Stone, who had begun to champion the history of the institution. Then it all went a bit Indiana Jones.

During this time, he maintained contact with the Council, and Stone, who had begun to champion the history of the institution. Then it all went a bit Indiana Jones.

Esbester said: “Neal Stone and Matthew Holder (current head of campaigns at the Council) contacted me about some material that had been found in Mansfield (picture, left). It was in pallets, in a warehouse, with bundles on the shop floor. There was a lot of paper-based material and a lot of the posters.

“We had a day and a bit to get on-site and have a look at it.”

The question then became: what are they going to do with it? This, Esbester says, is the origin story of the Council’s digital archive.

“We wanted to champion it,” he continued, ” but we needed the support of the Council board to do so. Archiving it was certainly not going to be a cheap exercise and we needed their buy-in.

“The board of trustees was very supportive. It really is credit to them for putting the money behind it. They saw that it would be very good for the organisation in terms of awareness of the Council.”

Digitised archive

The archive was then digitised. Fluent in the machinations of archiving historical content, Esbester said it was a ‘big job’, although not as large as RoSPA’s archive.

The archive was then digitised. Fluent in the machinations of archiving historical content, Esbester said it was a ‘big job’, although not as large as RoSPA’s archive.

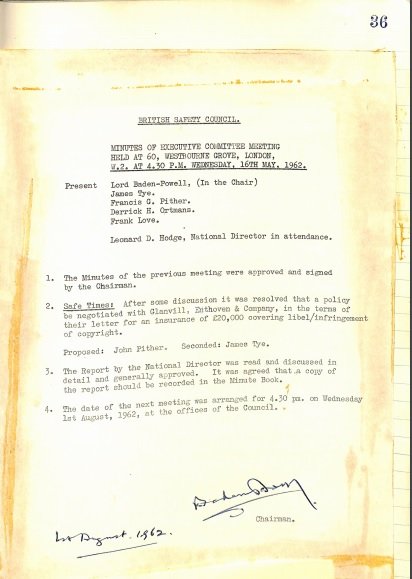

The material covered personnel records, minutes of meetings, ‘basically everything that had been done by the Council for several decades’.

The Council then took the decision to make the digital archive freely available.

“This was such a great move and such a great example of what an organisation does with its institutional memory.” Esbester said.

This, naturally, also led onto the book.

“I had been using it as part of my IOSH project that I was working on,” he explains, “and then, as part of the 60th anniversary of the Council, it was thought that something should be done with it.”

What was the process of making the book?

Esbester said that, as an academic, he would normally be thinking on a purely ‘intellectual focus of the work’. But this book needed to be broader. And specific to the practitioner audience envisaged.

Esbester said that, as an academic, he would normally be thinking on a purely ‘intellectual focus of the work’. But this book needed to be broader. And specific to the practitioner audience envisaged.

It also had to be honest and truthful.

He said: “One thing I must stress, I am an academic, and intellectual freedom is something I am used to – but there were bits of the Council’s past that are controversial.

“But Matthew and Neal said, ‘this is a fair question’, so we will need to talk with the board of trustees.

“But they came back and said it was absolutely fine. They didn’t want to gloss over the past, and wanted to offer a fair representation of the Council, regardless of whether it contained things that they would not necessarily do now.”

Design and graphic portrayal

Having set down the agenda for the book, it then came down to how the book’s content would look.

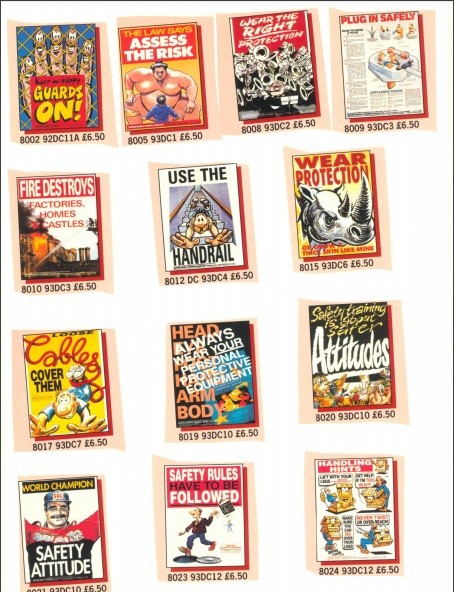

“We had an idea that it would be a graphic portrayal,” Esbester continued, “but the two aspects – the narrative and the visuals – came out alongside each other.

“The downside of a physical publication is it has to restrict all the images that were truly representative of the archive. So we did have to be selective.”

The original idea, in terms of narrative structure, was to group the content around sectors – manual handling, transport – but the team ‘got a bit twitchy’ about this approach as time went by.

He explained: “Matthew said he wanted to move away from the sector-specific thinking, especially with changing working patterns.

“We chose to go down a more thematic route – the shifting importance of health and work – and wanted to highlight the bigger themes of the health and safety profession.”

Demographic focus

It was important that the book was factual, accurate and informative, even if it was intended to be celebratory. It was also vital that it was not a ‘dull corporate history’.

“The book was designed to not be a piece of hagiography. Yes, it was designed to mark the anniversary, and have the practitioner attitude in mind. We also knew it had to be a larger scale format, and in colour throughout.”

“We wanted it to appeal to practitioners and for them to say ‘Oh look where we came from’ or even ‘We are still doing this now’.” Esbester explained.

The book’s designer, Dean Papadopoullos, was crucial to the creation of the content and narrative alongside Esbester.

“He was looking at the physical aspect of how it would work. Historians don’t know how to handle visuals, and traditionally such work can be a bit poorly presented.” he said.

“So, by having a professional designer, it meant we could deal with it and make it attractive to the reader.

“It was all about using the book as a springboard to looking forward at the Council. The design had to reflect that.”

The Tye that Binds

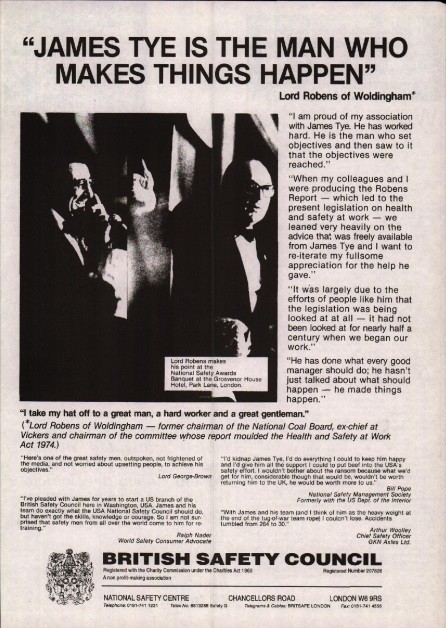

The other issue around content was the spectre of the Council’s co-founder James Tye. A bow-tied wearing, larger-than-life colossus of health and safety history, he died more than twenty years ago, and is no longer representative of the Council’s objectives.

The other issue around content was the spectre of the Council’s co-founder James Tye. A bow-tied wearing, larger-than-life colossus of health and safety history, he died more than twenty years ago, and is no longer representative of the Council’s objectives.

But he was the powerhouse behind the early years of the Council, and was instrumental in the creation of the piece of legislation that every single practitioner reading this article lives by: The Health and Safety at Work etc Act 1974. H

How best to serve his legacy?

Esbester said: “He set up the organisation in his own inimitable style. We wouldn’t want to avoid him, but there was a radical shift in the organisation after his death and what the Council has become today.

“It is a question of balance. The first 40 years, but then also the next 20 years.”

One interesting element of the organisation’s history with Tye is the British Wellness Council. Setup in 1980, it illustrated how Tye was ahead of his time in thinking about wellbeing in the workplace. And the sheer range of activities he participated in.

“The Council was involved in a huge range of activities under Tye,” Esbester explained, “it was very good at raising awareness, but perhaps not seen as very professional, and was about stunts that gained publicity.

“When Tye died, it moved from the broad public safety issues to a point, to OSH.”

Esbester is still looking for answers on the Wellness Council. “It hasn’t left much of a document-trace. We’ve had people try and find people who worked with him on it.”

He also relates that the general history of the Council, and Tye’s place within it, was about ‘getting the public involved with health and safety’, from the 1960s onwards, and trying to make them realise the importance of it.

Although has the creation of the sensationalist, tabloid ‘health and safety gone mad’ culture, damaged that legacy?

“It can be quite disheartening to see some of the issues from the 19th century cropping up in different ways now.” Esbester said.

The importance of archiving

A lesson in the importance of archiving organisation’s minutes and material was showcased by the creation of the book. Unfortunately, the Council’s collection is incomplete around the time of the 1974 act. The minutes of meetings, Tye’s material and all other notes are currently lost.

A lesson in the importance of archiving organisation’s minutes and material was showcased by the creation of the book. Unfortunately, the Council’s collection is incomplete around the time of the 1974 act. The minutes of meetings, Tye’s material and all other notes are currently lost.

“We know a lot of what the Council did from the minutes. We were happy to include the minutes in the book. Someone had retained them in Hammersmith (the head office of the British Safety Council), but unfortunately 1974 was missing.”

Indeed, in terms of the content, the book was driven ‘by the archive’.

“There was lots from the 1980s and 1990s in the archive. The missing material may turn up elsewhere, but probably not in a big cache.”

“If there is one lesson I want to come out of this book, it is the importance of archiving and keeping material for history. The book is a great example of that.

“If people don’t know about what has been done before, they could make the same mistakes again. And at least then you understand, and stops people reinventing the wheel. Because without knowing about the past, how can we learn in the present, and inform the future?

“I’m not suggesting that we use the 1970s to learn lessons 2017. It’s just about encouraging people to keep hold of their institutional past.”

The changing nature of work

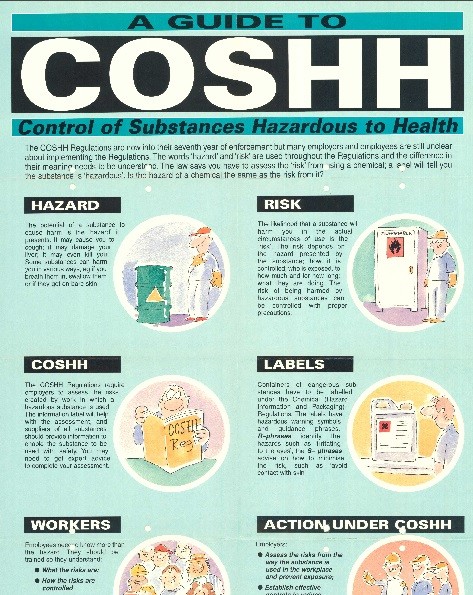

One of the core topics the book assesses in its visual and text content is how the workplace has changed. This includes the type of jobs that people undertake in the 21st century compared to the last few centuries.

One of the core topics the book assesses in its visual and text content is how the workplace has changed. This includes the type of jobs that people undertake in the 21st century compared to the last few centuries.

It makes for a fascinating document of cultural change through the prism of the health and safety sector.

Esbester explained: “It is about looking at the gender balance, the sectoral balance, the changing nature of the manufacturing line, to the service industry and offices, and now out into home offices.

“We had posters and visuals in the early days of the Council of workers wearing PPE and googles. This changed in the 1980s with psycho-social issues – including mental health in traditional sectors like manufacturing and construction.

“This morphed into musculoskeletal issues and wellbeing in the office – as well as display units and stress and diet. It all crosses over in the workplace. We are at a very interesting phase for health and safety.”

Lessons learnt

So what does Esbester feel that his journey and the book teaches practitioners?

He said: “It’s about adaptation to what is coming next. One of the things the Council has tried to do is engage with stakeholders on all levels – from government, to policy makers, to the general public.

“It is about the idea of the breadth of coverage and engagement with people.”

The Safety Conversation Podcast: Listen now!

The Safety Conversation with SHP (previously the Safety and Health Podcast) aims to bring you the latest news, insights and legislation updates in the form of interviews, discussions and panel debates from leading figures within the profession.

Find us on Apple Podcasts, Spotify and Google Podcasts, subscribe and join the conversation today!