For the past nine months, Martin Amis has been living in his mother-in-law’s house, a grand, many-storeyed residence in downtown Manhattan to which he and his wife, the novelist Isabel Fonseca, decamped after a fire wrecked their home. This was the place in Brooklyn where they had been living since 2011, and almost a year after the fire – the result of a defective chimney and which, Amis says, broke out on New Year’s Eve like “the last kick in the arse of 2016” – he still looks like a man who has suffered a shock. In the gloomy drawing room, he moves stiffly around nursing a back injury, ruefully enumerating the ways in which old houses can ruin one’s life. The property was salvageable, but the couple’s peace of mind was not, and they will soon be moving to a new home, an apartment in a skyscraper in downtown Brooklyn. “It’s on the 20th floor, so you are up there in the clouds,” he says. “It’s going to be very heady, certainly to begin with.”

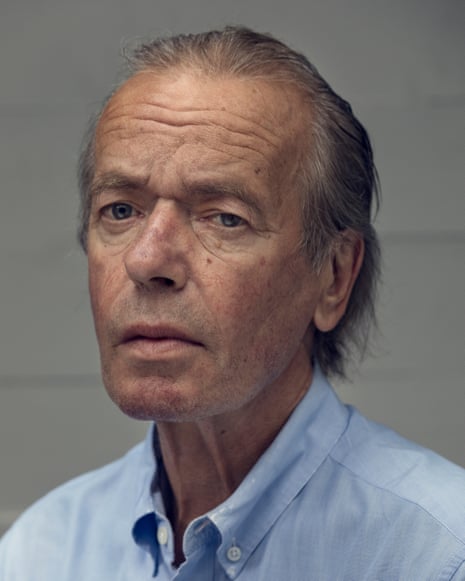

It seems strangely fitting that, two years shy of his 70th birthday, Amis should be plunged into a modern setting, although the very idea of Amis at 70 is somehow absurd. For many, he is frozen in time as he appeared in the late 1980s and early 1990s: young, rangy, belligerent, chucking out neologisms with a verve readers found either delightful or altogether too much. Amis as elder statesman doesn’t compute, not for any lack of gravitas on his part – he is, as always, erudite, thoughtful, disinclined to hold back for the sake of an easier life – but rather for some quality in his writing, a youthful elasticity. He is still very much Amis, slyly commenting on the absurdities of his adopted American home, but this afternoon his energy seems tempered by a frailty of form. If an occasional note of hesitation creeps in, it serves as a reminder that, for even the boldest among us, age is a process of becoming steadily less sure.

The Rub Of Time, a collection of essays and reportage, goes back to pieces written by Amis for Tina Brown while at Talk magazine – notably, a long piece about the porn industry in 2001 – to an interview with John Travolta for the New Yorker in 1995, to recent thoughts for Harper’s about Trump. (“Above all, perhaps,” he writes of Trump, “his antennae are very sensitive to weakness... Trump can sense when an entity is no longer strong enough or lithe enough to evade predation... The question is, can he do it with American democracy?”) The most compelling among these are his pieces about writers, which suffer from none of the anxiety that can mar his engagements with pop culture. There is a crushingly good piece on Nabokov’s decline, but also wonderful essays on the genius of Larkin and JG Ballard, as well as loving tributes to Iris Murdoch, Saul Bellow, Christopher Hitchens and Amis’s father, Kingsley. “We are all of us held together by words,” Amis writes in reference to his father’s last days, “and when words go, nothing much remains.” Perhaps inadvertently, the book has an elegiac tone. In a piece about tennis, Amis wryly notes his own encroaching decrepitude: “The ball comes over the net like a strange surprise; you just stand there and watch until, with a senescent spasm, you bustle off to meet it.” (The use of “bustle”, here, a quintessential Amis touch.)

If America is, for Amis, an easier place in which to grow old – fewer critics, for a start – he retains an expectation that he and his wife will move home one day. “I miss the English,” he says. “I miss Londoners. I miss the wit. Americans, they’re very, well, de Tocqueville saw this coming in about 1850 – he said, it’s a marvellous thing, American democracy, but don’t they know how it’s going to end up? It’s going to be so mushy that no one will dare say anything for fear of offending someone else. That’s why Americans aren’t as witty as Brits, because humour is about giving a little bit of offence. It’s an assertion of intellectual superiority. Americans are just as friendly and tolerant as Londoners, but they flinch from mocking someone’s background or education.”

This is not an inhibition from which Amis suffers. His most recent spat in the British press was over a piece he wrote for the Sunday Times about Jeremy Corbyn in 2015, in which he mocked Corbyn’s lack of education, among other things, and which was considered by some to be unforgivably snobbish, a case of picking an unfair fight with the poor man who wants to be prime minister. “Two E grades at A-level,” Amis says now. “That’s it. He certainly has no autodidact streak. I mean, is he a reader? Hitler’s education ended when he was 17. Stalin was an incredible reader. Balzac, Dickens. I’m going back to all that now, because it’s the anniversary of the Russian Revolution. Lenin has been very much downgraded and Stalin has been, not rehabilitated for his crimes, but for what he was before the revolution. Not just published, but an anthologised poet. A lifelong autodidact. And capable of political poetry in a way Lenin wasn’t. But it does matter if leaders have some sort of backing.”

Corbyn’s success in the election has done nothing to raise Amis’s opinion of him. The Labour leader is, he says, “more cautious now, but still grimly ideological, and an admirer of tyrants – Chávez, Putin”, the beneficiary of a deranged electorate that, for different reasons, gave rise to Brexit and Trump. “It’s a sort of restless desire for change,” Amis says. “And also – this sounds like a conspiracy theory – but the internet, for all its incredible benefits, has had a stupefying effect, I think. It was always a Pandora’s box – its part in terrorism is malign. And it has made it difficult for people to concentrate.”

There’s a good line in one of the essays in the book: “We grant that hatred is a stimulant but it shouldn’t become an intoxicant.” Amis is referring to the sharpness of some of his friend Christopher Hitchens’s work, but it might stand as a description of the internet. “Isn’t it amazing, the wells of hatred? It’s a shameful confession, in a way, but I’ve never looked at social media.” Momentarily, his confidence retreats. “I was amazed when Salman did Twitter,” he says of another friend, Rushdie. But he did quit. Yes, Amis says, but “why take it on in the first place?”

It may be harder, in some ways, to be American than British – the terms of success in the US are narrower, with a greater emphasis on individual responsibility, so that, Amis says, there is “no honourable withdrawal” – but it is undoubtedly an easier place in which to be a successful novelist. Being the writer son of a famous novelist father was always going to play both ways for Amis, although he maintains that most of his early novels, from The Rachel Papers onwards, were written in relative darkness. By the time he wrote Money in 1984, and London Fields a few years later, literary novelists had been co-opted into celebrity culture. These were Amis’s reputation-making novels in comparison with which, and with a certain sadistic delight, reviewers judged later books to fall short. (Lionel Asbo, published in 2012, got a tough time, not least for the ridiculous name of its antihero, but this was nothing compared with Tibor Fischer’s assessment of 2003’s Yellow Dog, which Fischer likened to “your favourite uncle being caught in a school playground, masturbating”; Amis responded, “He’s a wretch.”)

Among his British critics, Amis excites a peculiarly angry commentary, partly on matters of substance and partly for reasons of style. No matter how many times he insists he grew up in shabby bohemia, he is earmarked as posh, or at the very least grand (he pronounces Darth Vader to rhyme with Prada), and whether real or a pose, his louche indifference to criticism only adds oil to the fire. When he moved to America, it was speculated with some glee that he was fleeing the press, which Amis is adamant wasn’t the case.

Nonetheless, he is happy to have escaped some elements of British literary culture. American novelists, Amis says, are less feverish about pecking order than the British. “They’re more realistic about it. Berryman, when Robert Frost died, said, ‘It’s scary. Who’s number one?’ Very unsentimental. At least status anxiety is overt here. And I think writers have a better time from the press here than in England. My historical explanation is that Americans wondered what sort of country they were living in, a new, young country, and subliminally saw that writers would play a part in telling them; not just a collection of Italians, Germans, Jews, but a real nation. In England, they don’t want to be told what they are. They’re quite clear on that, thank you very much.”

He gives it a moment’s further reflection. “And they think writers are just pretentious egomaniacs.”

If the election of Trump struck Amis with greater force than the disaster of Brexit, it is because, it seemed to him, it came more out of the blue. On election night in the US, he and his wife anticipated a win for Hillary Clinton, and were “rubbing our hands together over the size of the landslide”. The next day, he was put in mind of something Sebastian Haffner, the German historian, said after Hitler came in. “He said the feeling was not of horrror; it was of complete unreality. You go out into the street and people look different. The commerce, the cars; it all looks staged for your benefit. Completely make-believe. A sick-making feeling. And here it is. And what the fuck did they expect?”

We have walked down the street to a Japanese restaurant where periodically, over lunch, Amis will stand up to relieve his back. (He has not, historically, suffered from back pain – “the perks of being short” – but he hurt it recently.) Looking back over the decades, he thinks Trump has suffered a horrific mental decline. “If you look at old tapes of him on [US talkshow] Charlie Rose, using words like ‘chagrin’ correctly. And with a certain amount of ironic reserve.” There is, Amis says, a question of “dementia”.

The Hitler analogy, meanwhile, is one that strikes many, even on the left, as unhelpfully inflationary. Actually, Amis says, it is wrong for several reasons, not least because, “It’s always been Mussolini and not Hitler. Mussolini was completely ridiculous. He claimed he knew every language on Earth.”

But also, he says, because Trump’s ambitions don’t quite fit the totalitarian mould. “The slogan, which I used to see on bridges in Italy in the 1970s, was Mussolini Is Always Right. Trump is that crazy, and that boastful, and that deluded. Even Mussolini had a few good years before he lost it. But people like Hitler and Stalin wanted to change human nature. That’s what totalitarianism is. Trump doesn’t want to make a total claim on you as an individual. He wants to stay in power, and that’s about it.”

The question of impeachment, Amis suspects, is wishful thinking, though he suggests that a particular order of world event could push Trump over the edge. “I am, in a way, thirsty for an international crisis,” he says, perhaps unaware of how this comes across. “Not with North Korea; he’s itching to do that and thinks he’ll get the Nobel peace prize if he wipes it off the map. But I want something really ticklish, like the hostage crisis after the Iranian revolution, where he’s not going to reach for the button, but people are going to see him under stress.”

But, Amis adds, we shouldn’t underestimate Trump’s talent for stoking up unrest. “Trump is trying to stock up an army of neo-Nazis who, if he gets ousted before his term is over, are going to think it’s a coup. They’ve all got huge guns; that’s a sword to hold over the situation. That’s what they’re scared of.” This neo-Nazi element, which predates Trump, but which he has been very shrewd at exploiting, is something Amis sees as the last stand against Obama by the kind of American who “before 2008 could look out of his trailer and say, I may not be much, but I’m better than a black man. Then they see Obama, so handsome and witty and learned, and think, can I really say that?” Racism exists in Britain, of course, but he considers it a category difference. “It’s not to do with hatred from the gut.”

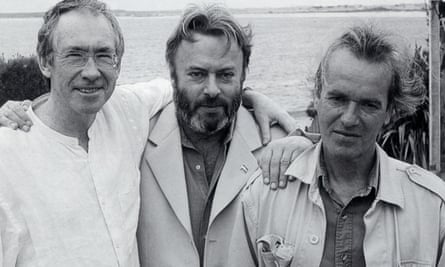

He wishes Hitchens could have been around to wrestle with Trump. In the new book, their friendship is very touchingly portrayed – they knocked around in their 20s when they worked on the New Statesman and part of the reason Amis decided to move to America was to be closer to Hitchens during the final days of his cancer, “hoping for a last spell with him. It was unclear how long he would live.” But Hitchens died in 2011, much sooner than Amis expected. He was in denial all through his friend’s last days. At the hospital in Houston, Amis spoke on the phone to Ian McEwan, who brought up something caustic Amis had written in a draft essay about Hitchens, a critique of his terrible puns. “And Ian said, you’re not wrong about that, but does he need that when he’s dying? And I didn’t say it, but I wanted to say, but he’s not dying!”

But he was. “It’s an awful thing, a death watch,” Amis says. “Especially now, because you have the machines telling you progress. The blood pressure falls. Human nature being what it is, you actually want it to end.” He wasn’t there for the very end. It was Hitchens’s son, Alexander, who informed Amis of his father’s now-famous last words: “Capitalism. Downfall!” Amis smiles. “Still the street fighter socialist.”

It sounds sentimental, he supposes, but after his friend’s death, Amis felt he had to take on some of his qualities. “He had a greater love of life than me. He really enjoyed everything, so much. I quite like life, but I’m not as crazy about it as he was. It somehow formulated itself in me that, now he was dead, it was my job to love life as much as he did. It hasn’t gone away.”

And in this age of political polarisation, one thing Amis is adamant about is the absurdity of losing old friends over politics. They disagreed violently about the Iraq war, which Hitchens supported. “He just hated Saddam, from the left, not the right. Although this drove him into some weird positions, like supporting Bush/Cheney in the re-election year, 2004. He would’ve given anything for a good outcome. But you’re not going to get a good outcome if you invade a country like Iraq, expecting people to welcome you for invading them.” But to have lost Hitchens as a friend over this would have been “self-righteous”. He saw it happen to his father, who “lost a lot of friends over Vietnam. And great friends, like Al Alvarez and Karl Miller. You can’t afford that. As Hitch said, you can’t make old friends.”

Amis is currently writing an autobiographical novel – “that I insist is a novel” – featuring not only Hitch, but Larkin and Bellow, as well as Amis’s late stepmother, the novelist Elizabeth Jane Howard, who married his father in 1965, when Amis was a teenager. The marriage lasted until 1983, but Amis and Howard were in touch, and close, he says, until the end of her life in 2014, though he retains some vestiges of guilt about an earlier phase of their relationship. “One of the perks of being the son of a writer is not that you come automatically equipped to write novels, it’s that you don’t bother much about praise. Kingsley never bothered much about praise and dispraise. My stepmother did care. She was desperate for praise, and very much wanted it from me.”

But for a while in the 1980s, after the marriage ended, Amis entirely refused to engage with her work. “I stopped reading her out of spite, because it was so disruptive when she dumped my father. His three children had to rotate to look after him.”

Recently, Amis read the Cazalet books, Howard’s family saga that spans five volumes, and was “incredibly impressed, particularly by the first two. Really marvellous, flashes of genius. In this autobiographical novel that I’m writing, I’m going to do some wish fulfilment. The Cazalet novels were a fantastic achievement, and in this novel I’m going to tell her.”

After the demise of his first marriage to Antonia Phillips in 1993 – he left her for Fonseca – his own family life has been low in drama. One gets the feeling that Fonseca insulates him from a lot of the bothers of daily life; he admits she handled everything after the fire. He has been a domestic creature for a long time, even when his children were young, preferring to work in the house, as Kingsley did, rather than go to an office. His eldest three, two boys and a girl, are now well into adulthood, but his two youngest daughters, to his delight, aren’t quite off his hands yet; 21-year-old Fernanda is a student at NYU and Clio, the youngest, is at 18 still living at home. Amis is hoping against hope she won’t opt for college in California.

Being a father has, he says, been vitally important to his life as a novelist. “I know a novelist who made the decision, very much thwarting his wife, not to have children, because he thought it would interrupt. And I thought: you’re so wrong. It’s a huge part of life that you’re excluding yourself from.” Of course, he adds, “quite a few other writers who’ve never had children – Philip Roth; Don DeLillo – write beautifully about children. But I was very broody. I did want kids. I was completely fed up with being single as well. I wanted to see a fresh face. Having children can’t help but open you out.”

What kind of parent was he when his kids were young? Not a shouter, he says. “Anger isn’t my thing.” When his boys were misbehaving, their mother, his first wife, would tell him to go in and lay down the law, but on the rare occasions he did, it didn’t go well. “Both my wives were capable of having a good shriek, but I can’t do it. It bores me, which is infuriating to my wife.”

How does he express anger?

“I have a mannerism that drives my wife crazy.” He looks away and does a mild tut. But, he says, “I do feel that, along with a harmonious marriage, having a good relationship with your children is the main bit.”

He and Isabel have, he says, been “lucky in all sorts of ways”. They can almost laugh about the fire now, at least at Fonseca’s initial reaction. She was in Florida when it happened, and when Amis called to tell her the house was on fire and there were six fire engines outside, she said, in her derangement, “When the firemen come, could you ask them to take off their boots before they go upstairs?”

Now in their temporary residence, work continues. Even here, Amis notices he has mellowed somewhat. He used to be a terrible purist about the terms on which readers should engage with his work. “Dryden said in the 17th century that the purpose of art is to delight and instruct, with the emphasis on delight. Because instruction is not always delightful, but delight is always instructive. And it has stood up very well.” He concedes it has taken him a while to get there. “I was snooty at some radio event where people read your novel – it was London Fields – and then you take questions from them, and a lady said, ‘I’m sorry, but I struggled with it.’ And I said, ‘Why?’ And she said, ‘I didn’t care about the characters.’ And I said, ‘Well, I’m afraid you should really not be thinking about that. You should be thinking about what the author’s trying to do.’ But I think she was dead right.” It is the truth before which all matters of style melt away. “You have to give a shit.”

The Rub Of Time, by Martin Amis, is published next month by Jonathan Cape at £20. To order a copy for £17, go to guardianbookshop.com or call 0330 333 6846.

Commenting on this piece? If you would like your comment to be considered for inclusion on Weekend magazine’s letters page in print, please email weekend@theguardian.com, including your name and address (not for publication).

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion