When Ali’s father-in-law had a stroke in the Iranian city of Shiraz last year, the 67-year-old shopkeeper was rushed to Namazi hospital, where he received treatment for 20 days, including six days in intensive care.

While his father-in-law recovered, Ali turned his mind to how he would pay for the care. He borrowed money to build up a 100m rials (£2,000) reserve. But when he picked up the bill, it amounted to just 5.8m rials (£116).

“We thought they may have forgotten to add a zero,” he told the Guardian. “I looked at my brother-in-law, and we laughed. This was considerably less, it was almost nothing.”

Before he fell ill, Ali’s father-in-law had joined the healthcare programme brought in during President Hassan Rouhani’s first term, a scheme announced in 2014 and nicknamed Rouhanicare, in apparent homage to Obamacare, Barack Obama’s patient protection and affordable care act. It meant that Ali and his family were only expected to pay a fraction of the total 128m rials.

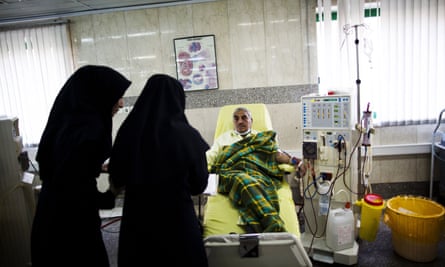

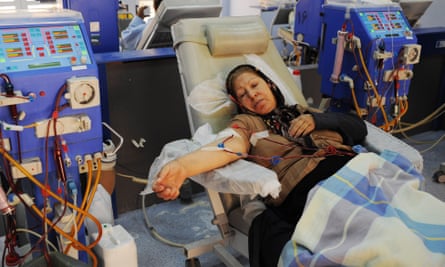

In the course of the past three years, Rouhani’s health ministry has insured nearly 11 million Iranians, meaning that those who were not previously covered, like the unemployed or the poor, are now protected.

The government’s bimeh salamat (healthcare) scheme pays 380,000 rials per person in monthly contributions, allowing most of those covered to pay a fraction of the cost of treatments.

Ali said he believed the healthcare plan was the president’s biggest unsung domestic achievement, and one that helped lead to a landslide election victory in May, which increased his mandate for his second term by 5m votes. Rouhanimeter, an independent website tracking Rouhani’s campaign promises, said it considers his pledges on healthcare to be a promise fulfilled.

“We have taken big steps to protect the social welfare of those with lower incomes and the nationwide healthcare plan’s implementation means all Iranians are now covered by medical insurance,” Rouhani said in his inauguration ceremony last month.

Initial estimates expected 5 million Iranians to apply for the scheme, but more than double that number have registered – many of whom did not dare to see a doctor previously for fear of the cost.

Shahram Shahbazi’s mother was an aerobics trainer in Tehran before developing a spine condition a couple of years ago that has left her housebound. “This healthcare really came to our rescue, otherwise we couldn’t afford the £5,000 needed for the surgeries,” Shahbazi, 27, said.

“It means that if she didn’t have the insurance, my mother would still be in pain and we would have to stop treatment after the first surgery. Under the insurance, you’re only supposed to have one big surgery a year, my mother had two and still they covered it.”

Despite the scheme’s success and popularity, it has not been without its problems. It is expensive – Rouhanicare costs about £770m a year, while other major health reforms, such as introducing a referral system and family physicians, means the annual healthcare bill is three times that figure. Rouhanicare’s funding comes from 1% of Iran’s 9% VAT rate and 10% of reserves saved through cut in subsidies.

Fars news, a semi-official news agency allied with the opponents of Rouhani, claimed last year that Rouhanicare was “on the brink of collapse” because it was not expertly thought-out and lacked funding.

“The nationwide healthcare plan is facing serious financial problems and state insurance agencies are saying that they are not able to pay back their debts to hospitals and it’s more than 10 months that they are facing those debts,” a Fars article said. Officials have admitted to the lack of funding in initial years.

Hossein Nafisimofrad is a graduate in business management at the University of Warwick who has done research about Iran’s health transformation plan. He also sounded an air of scepticism, saying his evaluation showed the “state-funded policy” was aimed at avoiding political unrest, but would be ineffective and unsustainable in the long run because of its costs.

Although Rouhani has taken the credit for the healthcare plan, it was envisioned in law more than two decades ago and was partially implemented during Mohammad Khatami’s reformist presidency.

Iraj Harirchi, a deputy health minister and spokesman, said Rouhani’s emphasis on the healthcare plan during his inauguration ceremony showed there was the necessary political will for its funding to continue.

“We’re proud to say that there is no Iranian without a medical insurance that we would refuse to cover,” Harirchi told the Guardian. “There may be some people who don’t want to apply, or there are issues with their IDs, otherwise anyone who registers can be covered.”

Nearly half of Iran’s population is insured through Rouhanicare or other means, with about 38 million having the government paying for their national insurance contribution. The rest are covered by medical insurance provided by their employers.

Most people using the government’s salamat insurance scheme contribute 6% of their overall treatment costs, and pay between 10% to 30% towards the costs of most drugs required for their care. Those assessed as unable to afford such payments are not charged.

“Before the [Rouhani’s] health transformation plan, people on average paid for 37% of their treatments costs, now they pay 6% and if it’s through referral only 3%,” Harirchi said, adding the reforms have also significantly reduced corruption and bribery in the health sector.

About 90% of the 11 million people covered by salamat insurance live in the suburbs. The government has recently decided that those who can afford should pay between 15% and 100% of their contribution based on an income assessment, but it was not clear when the new requirement would come into force.

Haririchi acknowledged that funding remains a challenge, but he was confident the government would find the money. “Iran’s population pyramid points towards an ageing population and this would increase the health and treatment costs so we would need more money.”

Vahid Rosoukhi, a contractor specialising in software working in the healthcare sector in Tabriz, north-west Iran, said recent reforms had benefited those on low incomes, but added that more money was needed to meet demand.

“A big challenge facing the healthcare is the bigger picture. From the beginning, we’ve heard criticism from doctors citing its huge financial burden and the government access to limited funds. That’s why from the beginning of this year, the government has relaxed some of its duties under the healthcare and limited its use to state-run health centres,” Rosoukhi said, referring to a cabinet decision this summer which restricted patients covered by Rouhanicare to only use state hospitals and doctors.

Hundreds of nurses have protested in front of the Iranian parliament, Majlis. In February, they complained that Rouhanicare has increased pressure on them, while their salaries have stagnated.

Outside the medical profession, others view Rouhanicare as a success, even those who did not vote for the president, including Roshanak, 39, a computer engineer based in Tehran.

“I don’t know why he kept focusing on the nuclear deal during his election campaign while it was the healthcare that had the most tangible effect on those with lower incomes,” she said.

“Before this plan, many people didn’t even dare to go for a checkup or treatment because they were afraid of the costs but you look at people now and everyone has got a daftarche (insurance notebook).”