Can Repairing Your Brain’s Wiring Help You Fight Addiction?

U.S. opioid deaths are soaring as the costs of drug abuse approach $200 billion a year. Neuroscience offers new ways to fight the epidemic.

Every 25 minutes in the United States, a baby is born addicted to opioids.

That heartbreaking statistic is but one symptom of an epidemic that shows no sign of abating. The 33,000 overdose deaths from opioids in 2015 were a 16 percent rise over the previous year, which also set a record. Drug overdoses are now a leading cause of death among Americans under 50—but only part of a broader addiction landscape that ranges from drug and alcohol abuse to obsessive eating, gambling, and even sex.

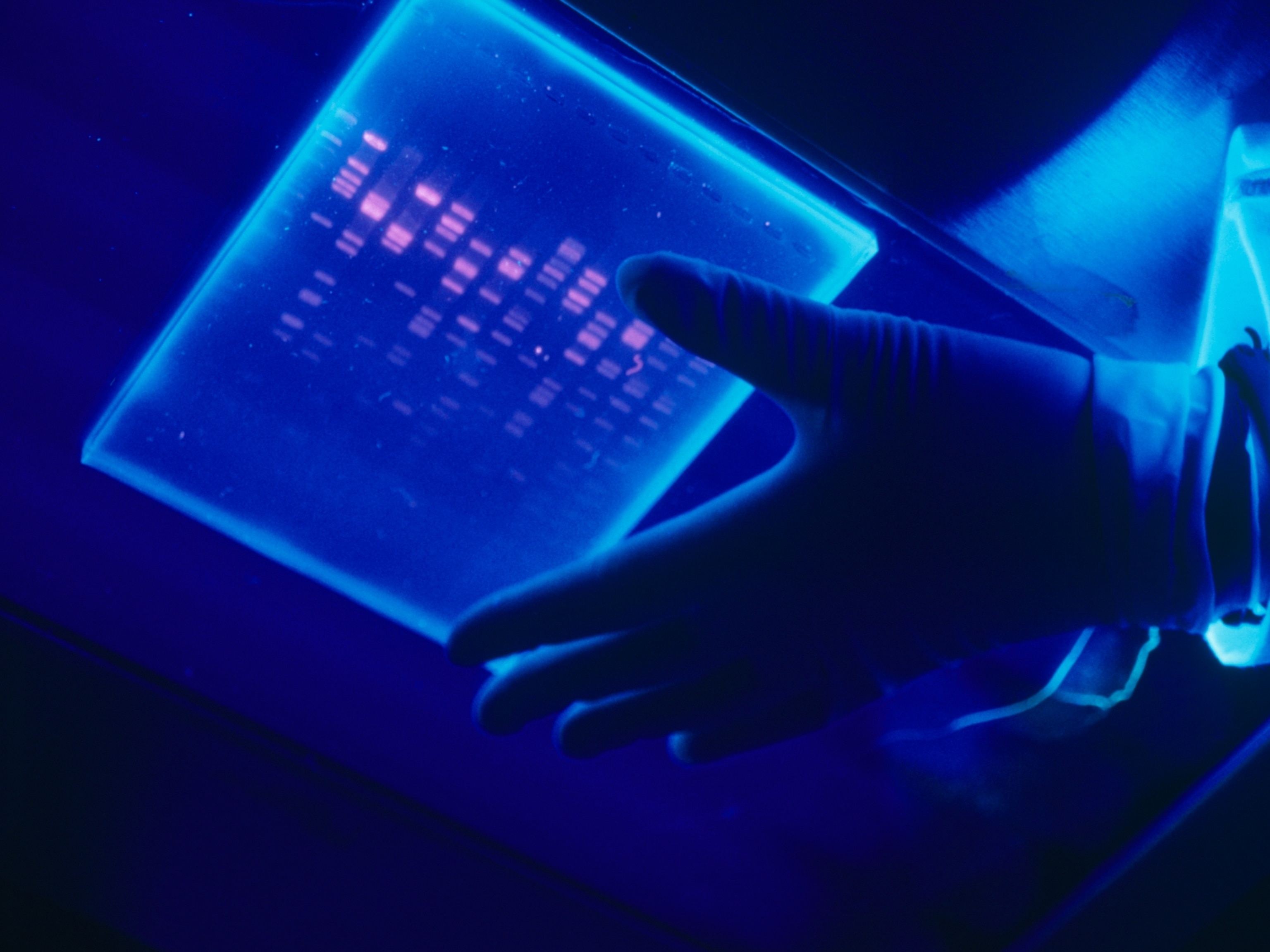

For this month’s cover story, “The Addicted Brain,” we went in search of the “why.” Why do human beings get addicted to substances and behaviors we know will harm us? What can new research tell us about addiction and the brain? Most important: Can what we’re learning help more people recover?

“Not long ago the idea of repairing the brain’s wiring to fight addiction would have seemed far-fetched,” medical writer Fran Smith reports in our story. “But advances in neuroscience have upended conventional notions about addiction—what it is, what can trigger it, and why quitting is so tough.”

The very nature of addiction is being rethought. In 2016, when he was U.S. surgeon general, Vivek Murthy—who’s interviewed in this issue—affirmed what scientists had contended for years, as Smith says: “Addiction is a disease, not a moral failing. It’s characterized not necessarily by dependence or withdrawal but by compulsive repetition of an activity despite life-damaging consequences. This view has led many scientists to accept the once heretical idea that addiction is possible without drugs.”

Still, drug abuse takes a huge toll nationwide: nearly $200 billion a year in costs related to health, crime, and lost productivity. Nowhere does this play out more starkly than in West Virginia, which owns what Senator Shelley Moore Capito calls an “unfortunate distinction”: the nation’s highest rate of drug overdose deaths.

A native West Virginian elected to the Senate in 2014, Capito sees the issue in personal terms. “The most heart-wrenching part is that it hits everybody … I’ve been in meetings where they tell you to look to the right or the left and say, ‘That’s what a heroin addict looks like.’ ”

What she’s learned, she says, is that turning the corner will require a spectrum of solutions—everything from more support at the state and federal levels for treatment and prevention programs to more facilities like Lily’s Place, a Huntington, West Virginia, medical center for babies born dependent on drugs.

Seeing the suffering, Capito says, “I’ve learned not to be quite so judgmental.”

Thank you for reading National Geographic.

Go Further

Animals

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Environment

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

History & Culture

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Travel

- Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico