How Medicaid, and its costs, grew in Nevada

Nevada’s Medicaid program, caught in the political crossfire over rising health-care costs, is far different than the limited federal-state health insurance partnership for the “deserving poor” that President Lyndon Johnson unveiled in 1965.

As documented in the first installment of the Review-Journal’s Hard Medicine series, Nevada has a lot riding on the debate over Medicaid. The Silver State is one of 31 states and the District of Columbia that used a provision of the Affordable Care Act to expand their Medicaid programs. As a result, 637,795 Nevada residents — about 20 percent of the total state population — now get some or all of their health-care costs paid through the program.

Republicans have vowed for years to “repeal and replace” the ACA, better known as Obamacare, which they consider fiscally and socially irresponsible. They have not yet been able to do so, but if they eventually succeed, Nevada will have to replace $300 million in annual federal Medicaid funding, dump 224,381 people as of March from the program’s rolls or find some middle ground that would increase costs and eliminate coverage for fewer recipients.

To grasp the controversy over Nevada’s safety net for the poor, and Medicaid in general, it’s important to understand how the program has grown and expanded since LBJ, its principal architect, signed it into law. It entered the annals of U.S. law almost as an afterthought. On July 30, 1965, Johnson put his signature to two amendments to the Social Security Act of 1935 in a carefully staged signing ceremony at the Truman Library in Independence, Missouri.

One created Medicare, a federal health insurance program for people over 65. Former President Harry S. Truman was on hand and was immediately enrolled as Medicare’s first beneficiary and received the first Medicare card, recognition that he was the first president to propose a national health insurance program in 1945.

Howls over Medicare, not Medicaid

The other amendment created Medicaid.

Howls over Medicare erupted months earlier when Johnson first floated the idea, which was immediately denounced by Republicans and the American Medical Association as “socialized medicine.”

“What ultimately became known as Medicaid took a back seat” during high-profile negotiations over Medicare, said Edward Berkowitz, a George Washington University professor acclaimed as the leading historian of Social Security and the so-called American welfare state.

In fact, the New York Times didn’t even mention Medicaid in reporting on Johnson signing the Medicare program into law.

At first, the lack of attention to the program may have been warranted. In the first year, some 19 million Americans signed up for Medicare, which was fully funded by the federal government. Medicaid, conceived as a small joint federal-state program to help the poor with medical bills, barely hit 4 million.

“Medicaid wasn’t seen as controversial in 1965. It was legislation to help what are known as the deserving poor … people not seen as responsible for their poorness, including disabled people, children and pregnant women,” said David Orentlicher, a lawyer and doctor and the new co-director of the health law program at UNLV’s Boyd School of Law.

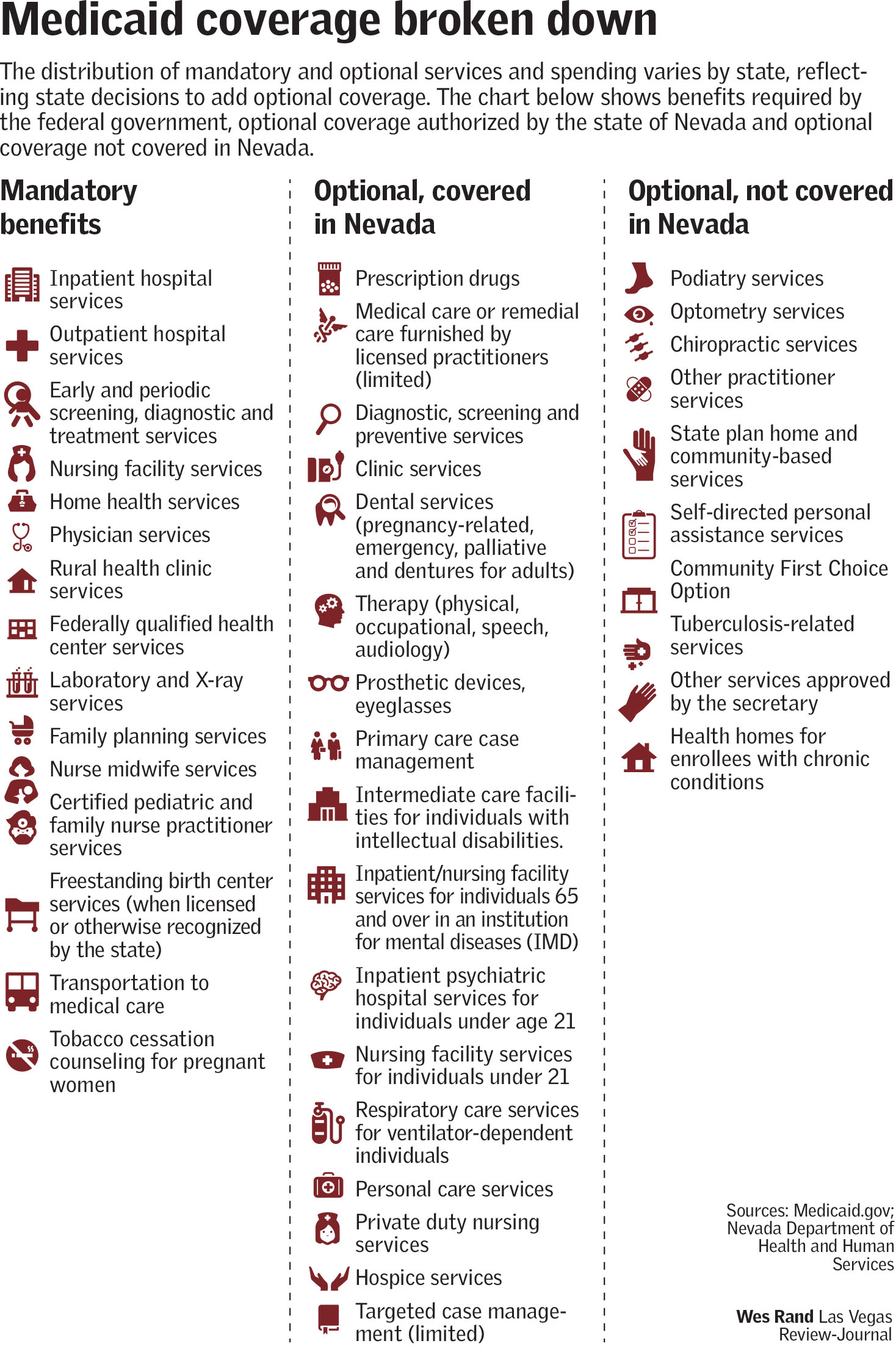

It began to draw more attention — and opposition — as it began to morph over the ensuing years, in part because of a provision designed to give states flexibility in how they applied it. States that chose to implement the program — as all eventually did — were required to cover specific populations and provide certain benefits to receive federal dollars to supplement state spending. They also could provide certain optional programs where the federal government would provide matching dollars.

When Nevada Medicaid enacted its program in 1967, it was called SAMI — State Aid to the Medically Indigent. The program then carefully mirrored the “deserving poor” construct of the federal law, covering the blind, individuals with disabilities, low-income children and their caretaker relatives.

But Mike Willden, Gov. Brian Sandoval’s chief of staff and the head of the state Department of Health and Human Services when the state expanded Medicaid in 2013, said Nevada’s program soon began evolving and expanding. Some changes were the result of federal additions of coverage; others reflected the state’s desire to leverage federal matching funds to cover more residents.

Program mission creep

The expansions in coverage include:

— In 1972, federal legislation required states to extend Medicaid to recipients of Supplementary Security Income, a federal program for the disabled.

— In the 1980s, federal expansions mandated states provide coverage to pregnant women, infants and more young children.

— In the 1990s, the federal government lowered financial eligibility requirements for pregnant women and children up to 18.

— In 2001, Nevada expanded its program to cover uninsured women under age 65 diagnosed with breast or cervical cancer or precancerous conditions.

— In 2008, Nevada Medicaid began covering prostate cancer screening for male recipients.

Nevada also is “a signficant waiver state,” Willden said, meaning it can get permission to use Medicaid dollars in ways that otherwise wouldn’t be allowed. For example, that could mean providing Medicaid coverage for the aged at home rather than only in a nursing home, he said.

The biggest single change in the program occurred when Sandoval expanded the state program as authorized by the ACA, resulting in dramatic increases in the number of recipients and the cost over the next several years.

Growth of Nevada’s program also has been fueled by a migration of many low-income seniors to the state, said Meredith Levine, director of economic policy at Nevada’s Guinn Center for Policy Priorities, a nonprofit, bipartisan policy analysis and research center.

“We have the fastest growing low-income senior population in the country,” she said, noting that many of the newcomers qualify for both Medicare and Medicaid.

State’s spending marches upward

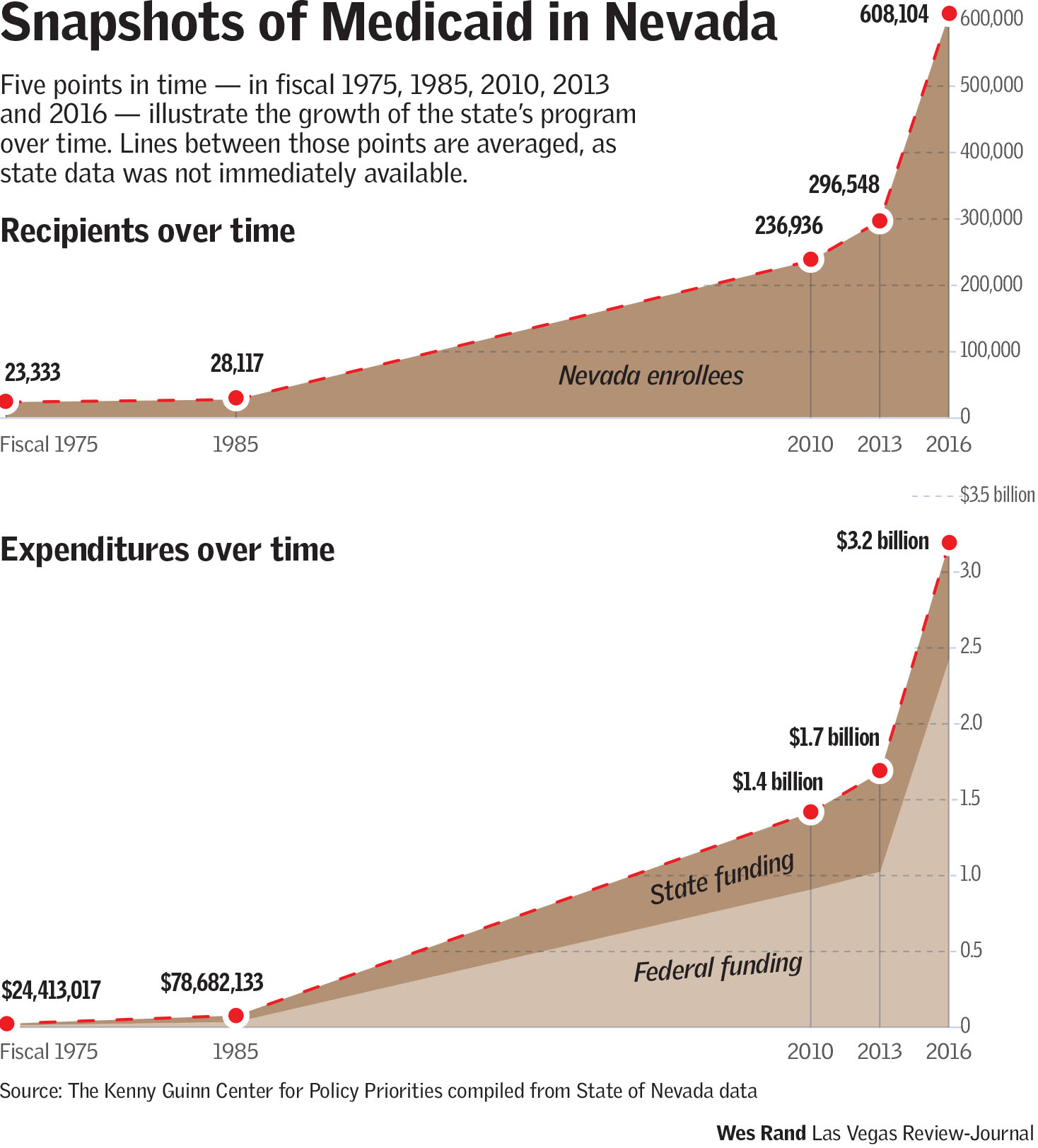

The steady expansion of coverage and the covered is easy to see in the state’s budget. In 1975, Medicaid spending cost $24.4 million and comprised 6.6 percent of the state budget, according to the Legislative Appropriation Report of 1986. Federal funding provided $13.3 million and the state share was about $11.1 million, with a small amount of county and other funding also included.

Today, Nevada’s Medicaid program costs nearly $3.23 billion, or about 27.1 percent of the total budget. That translates to $2.4 billion from the federal government and about $764 million in state funding. While Nevada’s rapid population growth has undoubtedly contributed to the increasing cost of Medicaid, that only accounts for a small slice.

State records show that while the population increased from 619,000 in 1975 to nearly 3 million in 2016 – a jump of 375 percent — the number of Medicaid enrollees skyrocketed over the same period. That figure leaped from around 23,333 in 1975 to more than 608,104 in 2016 — a 2,506 percent increase.

Medicaid’s growth in Nevada has been mirrored on the federal level. It now provides health coverage in some states to low-income, childless adults, the elderly, drug addicts, people with disabilities as well as almost two-thirds of the Americans in nursing homes. All told, some 74 million Americans receive Medicaid, nearly 35 percent more than the 55 million enrolled in Medicare.

Doris Kearns Goodwin, a former member of LBJ’s White House staff and later one of his biographers and close confidants, feels sure the Texan who rose from poverty to promote a “War on Poverty” never dreamed that any state would have more residents receiving their health insurance from Medicaid rather than Medicare.

“The focus back then (in the 1960s) was more on making sure the elderly could receive medical care,” she said. “But I’m sure he’d be happy with what’s happened. He had a special concern for people who couldn’t afford decent health care and now many people are getting it with Medicaid.”

Contact Paul Harasim at pharasim@reviewjournal.com or 702 387-5273. Follow @paulharasim on Twitter.

Nevada's cost per recipient

While many may think the increasing number of Medicaid recipients in the state also translates to high spending per enrollee, they would be wrong.

Meredith Levine, director of economic policy at Nevada's Guinn Center for Policy Priorities, a nonprofit, bipartisan policy analysis and research center, said that Nevada's Medicaid spending per enrollee is the lowest in the nation: $3,620 in 2014, the latest year available for that data, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The number one state in Medicaid spending per recipient is North Dakota, at $10,392.

— Las Vegas Review-Journal

RELATED

High-stakes health-care debate hits Nevada's Medicaid program