Did Airbnb Kill the Mountain Town?

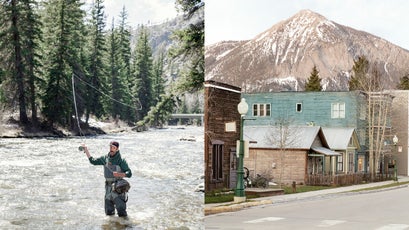

Living the dream has never been easy in the West's most beloved adventure hamlets, where homes are a fortune and good jobs are few. But the rise of online short-term rentals may be the tipping point that causes idyllic outposts like Crested Butte, Colorado, to lose their middle class altogether—and with it, their soul.

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

Brian Barker was living in Portland, Oregon, with a well-paying union job as a spokesperson for the fire department. But despite having “a job you don’t leave”—he had an itch. “I wanted to go live in the mountains,” he says. “I didn’t want to sit in traffic all the time. I was tired of living in the city.”

So he began searching. Missoula, Boise, Truckee—“anywhere within 30 minutes of a ski area.” In 2014, he relocated to Crested Butte, a 1,500-person-strong former coal-mining town nestled in Colorado’s Upper Gunnison River Valley. It’s often referred to as the last great American ski town, a distinction that locals, despite acknowledging it with a hint of self-deprecating smirk, do not really go out of their way to dispute. Phenomenal skiing aside, it is the sort of place where doors go unlocked (except, occasionally, to keep bears out); where locals on the Crested Butte Bitch and Moan Facebook page gripe about tourists (typically Texans) exceeding the 15-mile-per-hour speed limit downtown; where powder days mean closed stores and canceled meetings; where even the gas pumps at the local Shell station seem to take things just a bit more slowly.

“This is a great place to raise kids,” Barker, a divorced father of two young children, tells me one evening, wearing a baseball cap, a vest, and a hint of stubble. We’re seated at the Brick Oven, a locals’ hangout on Elk Avenue, the town’s main spine, where tidy wood-frame buildings in a rainbow palette glow beneath the snow-capped mass of the eponymous mountain.

Barker’s life seems enviable. He rents a “beautiful” place a mile south of town. He had his kids on skis practically before they could walk. He has a job he loves, as marketing manager for the town’s Adaptive Sports Center, a nonprofit that gives people with disabilities the chance to participate in outdoor activities. “They ski down that mountain,” he says, “and now they realize they can ride the bus to the grocery store.”

This postcard existence comes at a price, though. The cliché about remote adventure-town idylls is that people either have a second home or a second job. Barker has three jobs. “I produce videos on the side—I just shot my first wedding. Oh, and I drive an ambulance,” he says, laughing. “As a single parent”—his ex-wife lives 35 minutes away, in Gunnison—“you pretty much have to work multiple jobs.”

Not long ago, Barker stopped by the property-management company that oversees his rental to talk about a water heater on the fritz. “The manager said, ‘I know you have kids, but the owners are thinking about turning your place into a VRBO. You should probably start looking.’ ”

Barker suddenly found himself in the eye of a gathering social and economic storm, caused by the rise of the online short-term rental. From Barcelona to Boston, the world has been grappling with the arrival of home-sharing platforms. Amid any number of skirmishes—neighbor against neighbor, tourist against townie, lobbyist against legislator—cities have scrambled to get a handle on this “wild west” (one of the most common descriptors of the new home-rental landscape) and rushed to enact regulations. Everywhere you look, the battle is raging. In Flagler County, Florida, just north of Daytona Beach, 150 people turned out for a March meeting over a bill, backed by home-rental companies, that would limit how local governments can regulate short-term rentals, or STRs, as they are now frequently abbreviated. In Asheville, North Carolina, the issue proved so contentious that, late last year, a task force created to study STRs publicly splintered, according to the local Citizen-Times. In March, the city of San Diego—where residents of neighborhoods like Ocean Beach have decried the loss of local identity as rentals have proliferated—had to move a meeting on STRs to a bigger venue because of overflow crowds.

In the Mountain West—“God’s country, renter’s hell,” as one alt-weekly tagged it—where towns are already chronically beset by housing shortages, traffic problems, and the invariable ambivalence about sharing one’s slice of heaven with the tourists who help sustain it, the entrance of Airbnbs and VRBOs and HomeAways has heightened the tension. Some places, including Boulder and Denver, have passed tough regulations that permit only primary residents to rent out their properties for short periods. Other towns have taken the opposite tack, changing laws to allow previously illegal renting that was already on the rise, as happened late last year in Missoula, Montana.

In Bozeman, in Ketchum, in Jackson, in just about every destination or gateway town, one hears a similar murmur: not only are short-term rentals squeezing the last drops out of the housing supply, but more profoundly, they are threatening the very character that drew in locals—and tourists.

This is precisely the drama playing out in Crested Butte, and Barker has found himself cast in an unwanted walk-on part. “I’m literally losing sleep over the fact that I don’t know where I’m going to be living in a few months,” he tells me. He has tracked down countless leads and joined multiple waiting lists for deed-restricted housing reserved for local workers, which comprises 21 percent of the town. He does not own a dog, despite his kids’ pestering, to make himself a more attractive tenant. He has talked with the Regional Housing Authority about Section Eight housing, the national program providing assistance to low-income renters. “Which I qualify for,” he says pointedly. “It’s pretty humiliating, at age 41, to ask the federal government for help with housing.” He does not want to leave the area, for fear of putting his child custody in jeopardy. “I’m scared,” he confesses. “I’m kind of trapped in paradise.”

Later, as I walked back to the place I had rented—via Airbnb—a few blocks away, I thought of a line I had seen on the site: “Live like a local.” But what happens when locals can’t afford to live like locals?

We tend to think of the housing market as a large, impersonal, quantitative thing. Prices rise because of increased demand and constricted supply; they fall when the opposite holds. But to revise the old saw, the singular of data is anecdote. Stories about actual people. I wondered what part I—as the consumer of an STR—was playing in this story. Were my few nights contributing to people like Barker getting kicked to the curb?

In Crested Butte, I was staying in a small house—a former miner’s cabin—near the heart of town, so small that several nights in a row I actually wandered right past it. (Not helping matters was the fact that it was enveloped by towering snowdrifts.) I had been lured by its historical charm, its sauna and hot tub, and, as advertised, its location: “Easy walk to Elk Avenue, Nordic Center and just across the road from the FREE town shuttle to the ski area.”

I stay in Airbnbs and the like for the same reasons you do. Because I have a family and I want to cook and have multiple rooms. Because I have bikes or other equipment and don’t want to be hassled by the front desk. Because I indeed want to “live like a local” in a quiet, quaint neighborhood. STRs have become so familiar that they already come with their own rituals and clichés, their own weird sense of déjà vu. There’s the three-ring binder stuffed with brochures, the tips from the host, the Wi-Fi password. The odd box of pasta and random condiments. The signs that speak to the failures of previous guests. (In mine: “Please only use the remote to turn the fireplace on or off.”)

Then there is that odd sense, when you’re plunked down in the middle of a residential neighborhood, of being both an anonymous interloper and tenuously belonging. Margaret Bowes, who directs the Colorado Association of Ski Towns (CAST), told me that she had recently returned from a nordic-ski weekend in Crested Butte. “We were right in town,” she says. “And as I looked across the street at what are obviously homes owned by locals, I just thought, They must get so sick of seeing different faces walking in and out of their neighbors’ houses.”

I never saw much of anyone. (Those huge snowdrifts hardly helped.) I sensed their presence primarily through a notice in my rental asking me not to use the hot tub after 10 p.m. Noise (in Colorado, often associated with hot tubs) is one of the holy triumvirate—along with parking and trash—of ways that STR guests usually fall afoul of neighborhoods and stoke NIMBY fears. I committed none of these sins.

I thought of a line I had seen on the [Airbnb] site: “Live like a local.” But what happens when locals can’t afford to live like locals?

And yet, I thought, certainly a sense of residential community is defined by more than simply the absence of noxious behavior. Michael Yerman, Crested Butte’s town planner (like almost every man here, bearded and flanneled), lives in a deed-restricted part of town where STRs are not allowed, and he described how his neighbors had helped him dig out of his “snow cave” after the recent storm. “There’s a lot to be said for knowing your neighbors and feeling like they have your back when you need it,” he told me.

My rental, it turned out, was owned by a fellow New Yorker, Tony Powe, who spends two months a year in town. An Englishman and former restaurateur, he’s currently launching an app called WeLocals that “encourages people to shop locally.” He and his partner, on the hunt for backcountry skiing, stumbled on Crested Butte, fell in love, and bought the cabin in 2000. “It was one of the smallest houses in town,” and was inhabited, he told me, by a group of trustafarian skiers. The kitchen housed a drum kit. Initially, he rented to ski bums. After renovating roughly a decade ago, he decided to shift to vacation renters—partly, he said, because of “how our long-term tenants had treated the place,” but also “because we wanted to use it.” He employed a local property-management company, but after it began “stacking the house full of people,” he switched to Airbnb in 2013, which gives him more control.

Amid all the talk of restricting STRs, Powe wonders about unintended consequences. If, say, a 90-day rental cap is introduced, “what people will do is hike their prices a bit and they’ll make sure those 90 days are at peak season—and your shoulder tourism months will stop growing.” Powe, who is friends with plenty of locals, added, “If we can’t rent it, we just won’t rent it. It would stay empty for ten months of the year.” That means no guests like me spending money every night on Elk Avenue; no one getting paid to service the house.

Powe also suggested that STRs in many small towns are not the get-rich-quick scheme people expect. “It seems like you’re making a lot of money, because you’re charging for a week what long-term renters won’t even pay for a month,” he told me. But there are the unsold nights. According to data from research firm Airdna, the median occupancy of Airbnb rentals in Crested Butte is around 25 percent lower than in larger cities like Denver and San Francisco. Then there are the taxes and maintenance fees—“I think we spent $2,000 on snow removal in January alone,” Powe said. At the end of the day, he added, “I don’t think we make that much more money than if I did a long-term rental.”

From 19th century miners to 20th-century skiers, people have long sought a temporary abode in mountain towns. The difference now is how we’re finding them. “The stat I cite is that in 2010, 8 percent of leisure travelers used STRs,” says Matt Kiessling, with the Travel Technology Association (funded by Airbnb, HomeAway, and Trip Advisor). “By the end of 2016, that was projected to be one in three.”

As Ulrik Binzer, founder and CEO of Host Compliance, a San Francisco startup that helps municipalities track STR activity—mostly to help collect tax revenue—describes the trend, “It used to be a big commitment to rent your ski house. You had to hire a property-management firm, hide your personal belongings, sign a contract, and pay the property manager 30 percent of the spoils. A lot of people didn’t bother.” Today, he says, anyone with Internet or a smartphone can take a few pictures and become an STR host. Meanwhile, he says, “people are now more used to renting other people’s homes. You don’t have to go through the massive cleanup operation.” Consequently, STRs have soared. In 2016, HomeAway had more than 670,000 “room nights” in Colorado alone, up 24 percent from 2015.

Early on, says CAST director Bowes, STRs “were mostly just excess inventory—someone had an extra room, they weren’t going to rent it out long-term anyway.” Now, she argues, “it’s reached such a point that people buy homes for the sole purpose of renting them.” Indeed, as Host Compliance’s Binzer told me, “I have friends who pitched me on the idea of buying a place in Park City and renting it out during Sundance, basically paying the mortgage for the whole year.”

Seemingly no Colorado town has been unaffected by the rise in STRs, but their responses have varied. Durango, for example, has some of the most stringent regulations—limiting not only the number and location of STRs in the most desirable neighborhoods but also restricting them to two per block—so that vacation rentals, as Scott Shine, the town’s planning manager, told me, don’t “overwhelm a specific part of a neighborhood.” Breckenridge, by contrast, does not limit the number of STRs or rental nights, but early on it strove to make sure it had a regulatory handle on its STR stock—including collecting all applicable taxes.

Philip Minardi, who directs policy communications for Expedia—which owns HomeAway and VRBO—says that the company “welcomes the conversation of what good policy looks like,” noting rather tartly that such policy does not include a Denver law essentially prohibiting nonresidents from short-term-renting their homes. “We think it’s a smart move for cities to address how you regulate our industry in a responsible manner,” he says. “If a city wants to get to the heart of ensuring neighborhood character, that’s something they share with HomeAway—the reason why travelers are coming to communities is for the unique character.” Just how much of a conversation about policy Expedia really wants to have is an open question. The company has lobbied for legislation in some states that would limit municipalities’ ability to regulate STRs.

When I ask Marisa Moret, public-policy manager for Airbnb, for some best practices in STR regulation, she says that her company supports “clear and reasonable home sharing policies that benefit hosts and strengthen communities.” She adds that “Airbnb is an economic lifeline for many hosts who depend on the platform to pay their mortgage, raise their families, or make ends meet.”

After both my long-term tenants walked, VRBO let me make my mortgage payment,” one woman explained. “This is the middle class hanging on by its fingernails.”

For ski towns throughout the West, perhaps the most pressing challenge related to STRs is workforce housing. “It’s always an issue, and this has just exacerbated it,” Bowes says. “Homes that used to be rented to the workforce, that offered year leases, are suddenly being pulled out from under them and put on the short-term market.”

Not so long ago, in Crested Butte, this was scarcely a problem. As Melanie Rees, a housing consultant and former state economic-development official who lived in Crested Butte for 15 years, told me, “If you had asked during the recession, almost everyone would have said that we don’t have a housing shortage. There were foreclosures left and right, people were moving away.” But resort communities are “highly volatile,” she stresses. “One of the first things people give up when times are tight is their vacations and their vacation homes. One of the first things people do post-recession is go on vacation or try to take advantage of the real estate while prices are down.”

Crested Butte got its post-recession comeback. Owing in part to aggressive marketing, visitor numbers are up, particularly in summer. (More than one local told me that July is get-out-of-town month.) Then, “Enter the short-term-rental market, and wow did it create an opportunity that had not really been there before,” says Rees. Online platforms made all the difference. “People who were wannabes could now become owners,” thanks to the additional income. Between 2009 and 2014, the Crested Butte area was one of HomeAway’s top ten fastest-growing STR markets.

The implications of this growth were made clear to me one morning in Crested Butte’s town offices, housed in a stately brick building that was once the high school. There, after passing through a front entrance whose eaves were massed with snow (a sign warned me to LOOK UP), I found Dara MacDonald, the town manager, in a room whose door still bore the name of the teacher who’d once taught there.

“It’s a divisive issue for the community,” she said when I asked about recent discussions of STR limits. “People on both sides have valid points, and no one’s wrong.” On a conference table, she spread out a series of pie charts. In the first, labeled Free Market Housing Occupancy 1997, the category of short-term rentals is a mere 6 percent slice. By 2012, it climbed to 14 percent. By 2016, 29 percent. As she cautioned, the numbers are not exact, and there is some crossover—a short-term rental might be a local renting for just a few weeks or the month of July.

What most concerned her was another piece of the pie, one showing long-term rentals. Those shrank from 43 percent of the town’s free-market housing stock in 1997 to 24 percent in 2016. There, in statistical form, was the dry expression of Brian Barker’s poignant story: locals competing for fewer rental opportunities.

Nobody in the town’s government, MacDonald told me, thinks that limiting STRs “is going to solve the affordable-housing problem.” MacDonald, curiously, was the first person I met who lived in Crested Butte proper. This was possible, she admitted, only because she’s in a town-owned property. As Yerman, the town planner, told me, “The average home price is $900,000. You can make $100,000 a year and not have a chance.”

Which is why many feel that solving the Mountain West’s affordable-housing problem requires more than trying to curtail demand—you also have to increase supply. In Crested Butte, this is happening via new developments like the income-restricted Anthracite Place Apartments. In Steamboat Springs, the ski resort is offering cash bonuses to landlords who house employees. The Aspen Skiing Company recently hired a planner to deal with affordable housing.

One pilot program, in Summit County (home to Breckenridge and Copper Mountain, among others), is looking to entice property owners back into long-term rentals by providing free property management for landlords. The county is also offering a renter-education course to, as county housing director Nicole Bleriot described it, “raise the level” (i.e., quality) of tenants. This, she said, can be a tricky matchmaking dance. “We see a lot of larger homes, but we can’t find the right tenant mix to make it affordable. The other challenge is that since everyone in the county has seven sets of skis and three dogs, finding that pet-friendly opportunity has continued to be difficult.”

Dogs aside, living like a local has long been a precarious idea in the Mountain West. As Host Compliance’s Binzer put it, “If you’re a ski bum working the lift, or a waiter at a pizza joint, you’re competing with all these vacationers for housing.” In Crested Butte, this is aggravated by the fact that the town is encircled by protected space and largely built out. The biggest pool of housing in the area is 30 miles away—small wonder that the free shuttle bus between Gunnison and Crested Butte recently began making hourly trips in peak season.

STRs didn’t start this fire, but they have been a particularly combustible fuel. In most Rocky Mountain ski towns, any commercial development needs to mitigate its impact by providing a certain amount of affordable housing for its workforce. A long proposed new hotel in Crested Butte, for example, would have to create three new employee units. STRs dodge that requirement entirely. “Here, a whole industry came in and converted units into these lodging accommodations, and the housing impact was not mitigated in any way,” says Melanie Rees, the housing consultant. “It’s not a level playing field.”

In Crested Butte, STRs are providing much needed lodging. While Mt. Crested Butte, a small, tourist-focused settlement at the base of the ski area, has some 1,100 rooms in hotels and condos, the town itself has only a handful of small inns, with STRs now making up 65 percent of total lodging tax revenue. The rentals generate some jobs—although whether they’re the sort that sustain white-collar professionals like Brian Barker is another question. Is his dream—a solid middle-class life in a beautiful mountain community—now out of reach?

More than once, I heard a vague aversion directed against, as an editorial in the local paper put it, “people who think they have a natural entitlement to live in a sweet cheap house in town.” And yet I could also sense an inchoate fear that Crested Butte was in danger of losing what made it so desirable in the first place. Much of its last-great-ski-town aura comes less from its skiing than from its strong sense of identity (it was a working town long before there was a ski resort), its relative affordability (compared with, say, Aspen or Vail), and its quirky cast of local characters. “After a while, it wears on your community when your schoolteachers and folks like that can’t be a part of it,” said MacDonald. “They should be the ones coaching and volunteering and showing up for free music. When you drive home for the night and don’t come back, it’s harder.”

Barker knows that his path may end downvalley, in Gunnison, home to any number of ex-Buttians. His realist outlook does not mask his frustration. “I’m a part of this community. I work at our biggest nonprofit. I’m a firefighter. I’m involved in the arts. I’m a dancer. This is my town, this is where I want to be, and I’m getting kicked out,” he told me. “I know ski towns are expensive places to live—but they need people like me.”

On a Wednesday evening at town hall, several dozen residents were seated across the room from four council members. It was the eleventh time the council had gathered to discuss STRs since 2015. Roland Mason, the mayor pro tem, perhaps sensing the crowd’s weary resignation, noted that Denver took two years to set up STR regulations. “I understand that for those of you who have shown up for every meeting, it seems tedious,” he said. “At the same time, this has been one of the most difficult policy issues I’ve had to deal with in seven and a half years.”

I had been told by Steve Ryan, a former Oklahoman who runs a local property-management company, that early on, as possible limitations were floated, the council meetings had been “inundated” with attorneys and second-home owners. Now the group was pure Crested Butte: boots, flannel, tanned faces with ski-goggle lines. “The problem is getting drilled down to the folks that it affects the most,” Ryan said.

Living like a local has long been a precarious idea in the Mountain West. “If you’re a ski bum working the lift, or a waiter at a pizza joint, you’re competing with all these vacationers for housing.”

After thinking about STRs for several days, it struck me that the whole deal, thorny and murky, seemed like the kind of quagmire that American political scientist Robert E. Horn has called a “social mess.” The STR issue meets any number of Horn’s criteria: “different views of the problem and contradictory solutions”; “numerous possible intervention points”; “consequences difficult to imagine”; and “no unique ‘correct’ view of the problem.” For every person that I met who worried about what STRs might do to their block, I encountered someone else who relied on earnings from their own STR to stay on that block. For every defense of one’s private-property rights, I heard a counter-defense to not have one’s private-property rights infringed upon by a de facto hotel setting up shop next door.

The complications in the meeting began with the fact that the town’s mayor was not present. He (along with another council member) had recused himself because he has rented his home out as an STR. Another challenge was the fact that while the council knew how many houses had STR licenses, it did not know how many of them were actually being used as STRs or how often. Then there was the vagueness of STRs themselves. As council member Chris Ladoulis explained, “What’s tricky here is that the commercial activity people are engaging in is letting people sleep there—and it’s really similar to what you do when you own the property as a resident. If I was running a nightclub or selling power tools, it’s easier to spot.”

Lurking beneath the thickets of bureaucratic procedure (the minutes from previous meetings, the grandfathered exemptions) was an anguished examination of the soul of an American small town—whether the people who loved it could afford to be there, whether love was in fact enough to save it. This wasn’t politics with a capital P; it was something far deeper. One woman described how, in 2008, “after both of my long-term tenants walked, VRBO made the difference for me—it made me able to make my mortgage payment.” STRs, she suggested, were a symptom of a larger problem: “This is the middle class hanging on by its fingernails.”

Another woman, a realtor, voiced a perspective I often heard from opponents of regulation: “I’m not sure what the problem is.” Crested Butte had spent money to bring more visitors, she argued, “but now we’re saying we don’t want them here.” Limiting STRs “is not going to lower the price in town. The town is going through the roof because people want to live here.”

One of the council members, a lawyer named Jackson Petito (who also spins discs on the community radio station), later offered a response. “The idea that we don’t know what problem we’re trying to solve—maybe we as a council don’t, but for me personally, the issue is a town without residents, a town without voters.” Jim Schmidt, another council member, mused aloud: “I don’t think we have a police officer that lives in town.” “The new guy!” someone cried out. “I thought he was in Mt. Crested Butte?” replied another.

In that small exchange I felt the very crackle of civic life; these weren’t abstract issues—they were the lives of people who were endlessly intertwined. Before the meeting started, Steve Ryan had told me that things might get contentious. “It’s democracy at work, it’s civilized,” he said. “Everybody drinks a beer or a coffee and goes in and throws tomatoes against one another.” Indeed, as someone told a speaker that his time was up, a man hissed from behind me: “Let him speak, you always do!”

Schmidt, drawing a breath, concluded: “Boy, after hearing everybody tonight, I’m having an even harder time coming to a decision.” Luckily, there were no hard choices to be made; voting on the most contentious restrictions would take place at a future meeting.

Afterward, stopping at a tamale joint for a late dinner, I ran into John Belkin, the town’s blunt-speaking attorney. As we nursed Mexican Cokes, he said: “If you can make it here and survive, you have essentially your own private ski area—some of the hardest skiing in North America.” But there are trade-offs. “You can’t make a ton of money. You might have to live in Gunnison. Each of us has to do our own evaluation of whether those sacrifices are worth it.”

As we headed out into the frigid night, we saw a man on a skateboard being pulled by a dog down icy Elk Avenue. We both smiled, in silent acknowledgment of a small perfect moment in the last great American ski town.

Contributing editor Tom Vanderbilt (@tomvanderbilt) is the author of You May Also Like: Taste in an Age of Endless Choice