On a recent afternoon, Liz Phair walked into her manager’s office in Beverly Hills, exasperated by the day’s social-media controversy: a Jezebel article that revisits Alanis Morissette’s 1995 debut blockbuster, and craps on it. “I honestly can’t believe that at this time in our political history, people are going to be venomous about Alanis Morissette and Jagged Little Pill,” she sighed.

Phair, now 52, knows what it feels like to have the tide turn against you. In 1993, Matador Records released Exile in Guyville, which won acclaim for its articulate mix of sexual candor and jibes at patriarchy. Ten years later, when she released Liz Phair on a major label, Pitchfork gave the album a rare 0.0 review, dismissing it as “hyper-commercialized teen-pop.” But Phair has never put much stock in typical markers of success. In October, she’ll release Horror Stories, the first of two planned memoirs that forsake rock-star gossip for keen, lyrical ruminations on key moments in her life. “It’s hard to tell the truth about ourselves,” Phair writes, but “our flaws and our failures make us relatable, not unlovable.”

Let’s start with something you tweeted earlier this year: “Remind me to tell you about the time I had no idea I had a two-month tour booked until my friend told me over lunch at the Chateau Marmont one day.”

That really happened. When I’m not working, I safeguard my time to go into a dream state and not have to think about the commercialization of my art or the commodification of myself. I take “Liz Phair,” I put her on a hanger, kind of like Mr. Rogers, and I put her away in a closet. I’m not “Liz Phair” anymore. I become the observer rather than the observed.

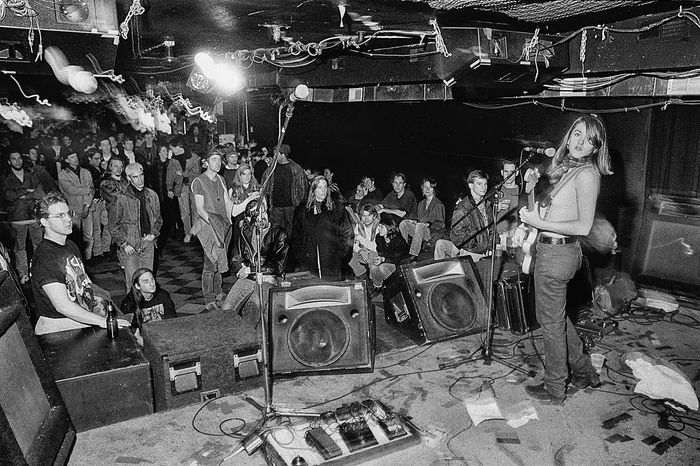

[In spring 2018], my friend Caroline had come into town, and we were having lunch. She said, “I’m coming to see you next month in Nashville.” I’m like, “I’m not playing Nashville next month.” She said, “I bought tickets. You’re playing Exile in Guyville in its entirety.” I was like, “Wait. What?”

This cold sweat went through my body. A couple of business calls must have come in and they wanted to book some shows, and I said, “Good, just do it.” No one actually told me when those dates were. It was two months of dates! I have stage fright anyway, and I had to go, in less than three weeks, from not having toured in years to playing the entire record of Guyville. When the tour started, I sobbed on my way to the first gig. I didn’t remember how to be that person. It took a few shows before I could be onstage and not freak out.

The bifurcation you describe, where the artist is on one side and the public figure is on another, is that a defense mechanism?

Yes, against self-consciousness. I can’t be an artist and think of myself as a star. I can’t do the two at the same time. Some people are born with a theatricality that I don’t have.

The Exile song that pops up in my head most often isn’t one of the famous songs, but “Canary.”

Interesting! That’s one of the more personal songs. It’s very revealing about the simmering repression I lived in, the soup I lived in, before I made music. I had a people-pleasing personality. And my older brother was in trouble so much that I was the designated good child. There wasn’t much room for my resentments and rebellion. That built up until I exploded.

How did you explode?

I stopped going to class in my senior year of high school. I’d been an almost straight-A student. I remember being in geometry class, and I kept getting 100s. They graded on a curve, and a guy I had a crush on, who I thought liked me, wasn’t doing so well in class. He turned around one time and looked at me with such resentment. He hated my guts.

I felt like there was not going to be a payoff for being a good girl, or being smart, or going to an Ivy League school. I remember thinking, Fuck it, I’m done with this.

You had an epiphany that being polite and industrious wasn’t going to pay off for you?

Or bring me fulfillment. Let’s throw the complication in here: I had a 15- to 20-year regret period of wishing I’d stayed on the straight and narrow. My life became getting onstage, when I was never someone who should’ve been onstage to begin with. The one thing that I really didn’t want to do became my whole job! And there was no way to get out of it.

Oberlin was the best school that would take me after I stopped going to high school. My not going to class senior year was a huge red flag almost everywhere, but Oberlin will take smart kids with emotional problems.

What were your emotional problems?

My brother had problems. So it made … [sighs]. I don’t want to drag my family through anything, you know? So I’m not gonna talk about it. But that was a stressor that was going on.

Were your parents accepting of your rebellion against upper-middle-class values?

Not at all. My mother went to Wellesley. My dad went to Yale. They’re intellectuals. The life of the mind, literature, theater, the symphony are all very meaningful to them. They had a good life, and they wanted that for me. But because I was adopted, they took a somewhat hands-off approach. Had I been their natural-born child, would they have allowed as much freedom?

One way to describe Exile in Guyville is as a concept album about a smart young woman who’s desperately trying to please these jerks who don’t deserve her, even though she hasn’t figured that out yet.

That’s a take that I could see. It’s not that they don’t deserve me — it’s just … and I still find myself saying to men, “You’re not listening.” There’s something about the society of men that thinks they have it all dialed in. “We made this. You’re living in a world we made for you.”

Great, but we made you. Right?

Exile was about believing in my perspective on life, against considerable pressure to conform to their takes on things. It’s about showing them that I can play their game and do all right in it. I felt constrained and invisible, and I wanted to kick their asses. Because you’re right, they were jerks. They acted smarter and more skilled than me.

My father was an infectious-disease doctor. Death, dying, and illness were things I knew about. It gave me a perspective that music is one of the good things in life. There’s no need to parse it to death. If you like a song you can hear at TGIFs, that’s fine. I was ahead of my time, in that sense. In the ’80s, there were clear winners and losers. That doesn’t exist anymore. Now there’s more diversity in our culture.

The Guyville song that brings it into focus for me is “Help Me Mary.” It’s almost spooky how you predicted the future. “Weave my disgust into fame / And watch how fast they run to the flame.”

Voilà.

It’s almost like witchcraft. Did you know fame was gonna happen?

If you talk to Matador, yeah. I walked in there and said, “I’m gonna make you a million dollars.” I had been prepared for what was cool because I dated guys in bands at Oberlin. I looked more naïve than I was. And I wrote those songs in a confessional way, as if I wasn’t making art, when I was. It appeared like I was some ingenue.

A brilliant primitive?

Yes. And I wasn’t. I was a sophisticated artist at that point — but angry and depressed and unhappy.

There’s a story that you cold-called Gerard Cosloy, who ran the indie label Matador, and said, “You should sign me; I’ll make you a million dollars”?

I wanted money from him to do a record. John Henderson, who ran the label Feel Good All Over, had been my roommate in Chicago. He heard my Girly-Sound tapes, and I was stuck living at home. He’s like, “Give me $100 a month and you can stay in my second bedroom.” And then he would sort of My Fair Lady me. “Listen to this music. Now listen to this.” I spent a lot of time going to see cool bands, standing in the corner and smoking cigarettes, so I’d look tougher and cooler. All the men who mansplained music to me made me better. But Henderson and [producer Brad Wood] were sort of fucking around — we couldn’t decide if we were going to finish recording the songs.

And this is very much me: I said, “What phone call do we need to make?” So yeah, I cold-called Gerard and said, “I need money to make a record. You should sign me.” I had one goal: to show these indie-rock boys that I had listened to all the music they gave me, and just because I liked the Police and R.E.M. and Madonna didn’t mean I couldn’t make indie rock. That was my goal, to be like, “Shut the fuck up about Green River versus Fugazi. It’s not that fucking hard!”

When you said you’d make Matador a million dollars, was it because you saw that there was an unfilled niche?

No! I thought I’d make a big splash in the indie-music scene. I didn’t know national attention would follow. I wasn’t thinking along gender lines. I wasn’t thinking about branding. Ooh, good girl says dirty things.

Good girl says dirty things is a fantastic concept.

That’s my brand! At Oberlin, that was part of the activism, that the female voice is the least listened to and carried the least authority. I even sped up the tracks on Girly-Sound to make myself sound even more like a little girl. My theory was, if I say the dirtiest things in the world, but like a little girl, will anyone actually hear it? That was the game I was playing. The person I was as a human being and the person people expected to meet were really far apart.

Whom did they expect to meet?

Someone taller. Tougher. Scarier.

Were there also assumptions about how easy it was to get you into bed?

Yeah. There was a period when everyone was saying I’d slept with them, and I hadn’t. That seems to be what I remember from my early 30s. And it pissed me off. Who are people going to believe on the witness stand, the girl who’s a blow-job queen, or some guy? I get hit on a lot. Everybody sort of takes a shot.

Because men think you’re game?

Not just that. It feels like I understand the male mind better than some people. This whole idea that men just want sex, I don’t think that’s true. I think they’re actually looking for intimacy. To them, sex equates to a moment when they can step out of their tough masculine mind and be in a really Technicolor vulnerability. I think that’s more what they’re craving.

So when your indie record Guyville became a phenomenon, was that difficult?

Yes. If I’d only had success in the indie world, my music would have been contextualized more accurately. They would have understood a little more of the art project behind it. Rather than thinking that I was literally saying I wanted to be your blow-job queen, you know?

Once you’re in a wider world, and People magazine picks it up, the nuance is gone. And of course, Matador was like, “Keep going! We’re doing great!”

“Keep up the blow-job songs.”

“More blow-job songs!” I was in no way prepared for the attention. I’m shy. I’m not trained or skilled in any of these things, so I was sucking at everything I was doing. Matador was great, but emotionally, I didn’t have any help. Suddenly, the attention was national and my parents knew about it.

Was that a surprise?

I didn’t think they would even hear the record. I believed that only Wicker Park and maybe Brooklyn and the Pacific Northwest would listen to it. I mean, I was also stoned a lot back then. So that explains some of it.

Your parents never asked you to send them a copy of your record?

No. They were quite disappointed that I was going into entertainment. While everyone else was saying, “You’re amazing,” my family was like, “You said what in public?” Fame is a dirty word in my household. Fame is awful.

So it’s not that you used the word cunt in a song —

No, it was that too.

But mostly, they thought entertainment was dirty and undignified?

Yeah. And you know what? The truth is, they were right. [Laughs.]

Did Exile have a cultural impact in the short term?

A lot of people knew about me who never really listened to the record. But, yes. I was someone people could relate to. Because I was more mainstream than the people I was around. More mainstream than …

The Jesus Lizard?

Yeah. And I had been a good girl for a very long time.

You said you were stoned a lot during this period. Was that to escape?

Probably. When I get high, the world shuts up and I can focus on creativity. I have to write sober, have to perform sober. But when I get high, my guitar playing gets so much more interesting. Where someone else would reach for a drink, I’d reach for marijuana because it would let that creative person come forward. But then I have to finish it — a song, my book — while I’m sober.

Let’s talk about your guitar playing, which is often overlooked and doesn’t sound like anyone else’s.

I’m very proud of that.

What do you do that’s different?

I’m weird. [Laughs.] I pursue wrongness if it excites me. In eighth grade, I learned the basic chords from a really wonderful guitar teacher. I was bored playing Dan Fogelberg and James Taylor, so she said, “If you bring me in two songs you’ve written every week, I won’t tell your mom.” As a visual artist, I look at the neck of a guitar as a canvas. I like to add jazzy notes or weird, wrong notes. I like dissonance. Brad [Wood] will tell you I lean annoyingly toward jazz. When I perform now, no one hears my actual guitar playing because of all the other instrumentation.

Tell everyone else to turn down.

I like the way we sound. I tour for one reason: the fans. I don’t make a lot of money at all because I stage it to within whatever budget we’ve got. I make some money, but not as much as you’d think. If you’re a rock star, you’ve got fun money. I never seem to get to the fun money part, and I’d like to.

When you made Funstyle, you were already making fun of yourself as a has-been who’d been forgotten by everyone. And that was eight years ago.

I’m not sure what you’re getting at.

Why haven’t you released an album since then?

I was going to work with Ryan Adams, and you can guess how that turned out. I stuck around for three years trying to get that done. Up until then, I didn’t want to make a record and tour while my son was in high school. It wasn’t until he left for college four years ago that I really wanted to put a record out. During the puberty years, the teenage years, you have to be around more. That’s when it gets very real.

What are you going to do with the songs you made with Ryan Adams?

Nothing.

Did you finish any songs?

No. Started a lot. We kept trying. But he was unreliable, and I wasn’t willing to go along with his process.

What was his process?

I’m not gonna go. Sorry.

In your book, there’s a chapter called “Hashtag” where you talk about working with him. You also detail the number of ways you’ve been sexually harassed, both as a woman and as a musician. But I think the chapter says that it’s not only harassment that affects women, it’s less obvious things, like being ignored or discouraged.

That’s very true. It goes back to being a child: “Sit still and look pretty.” You want to have a voice, and if you’re female, they block off your avenues to do that. When I think about #MeToo, I think about my determination to continue forward.

You also write about Adams, “Did he hit on me and try to get me to sleep with him? Yes. Did I take him up on it? No.” What happened when you didn’t take him up on it?

That was a sentence that was flagged by my editor, and I’m beginning to see why. That’s nothing. Guys hit on girls all the time.

Can I ask a question? Out of everything in the book, why is the Ryan Adams thing such an interesting topic?

Because he’s been in the news, and it’s a pithy way to discuss sex and power.

It worries me. There’s an aspect that ends up being reductivist, and it contributes to the problem rather than solving it. It’s gossip. The real aspect is, can women be heard? Can we work and be equal contributors?

You’re not the only one singling out Ryan Adams as a hot talking point, and it’s sad. It does need to be talked about, but so do the larger issues.

Let’s talk about the Liz Phair album …

I want to talk more about Funstyle! [Laughs.] Nobody ever asks me about it. I love listening to those joke songs. I listen to Funstyle more than a lot of my other material. Those songs aren’t gonna help you with your emotional problems. It’s what we did in the studio when I was scoring television so I could stay home with my son. Funstyle was an example of me meeting plug-ins, which are effects you can use to manipulate sounds, like a filter on Snapchat. You can’t help but want to fuck around with them.

Liz Phair was an album some Guyville fans hated because you tried a mainstream sound. When you were co-writing with the Matrix, the production team who’d worked with Avril Lavigne, what did they show you about how to write a pop song?

Pop songs are written very fast, which was a surprise to me. The lyrics had to be broad — I was always trying to put in specifics, and they’d allow a few. But the language and the concept have to be broad.

I get a big high out of throwing myself into something new. As my mom said, “Oh, great, something else you’re not qualified to do.” If there’s something I’m not qualified to do, it’s a sure bet I’ll jump right in and do it. I didn’t consider Liz Phair the same as Whip-Smart or Whitechocolatespaceegg. I can compartmentalize. None of this is me. If you want to know me, come see my visual art. Meet me when I was 9. “Liz Phair” isn’t me, so what does it matter if I’m co-writing?

Isn’t Whitechocolatespaceegg a precursor to Liz Phair — a little bit of a warning that you would leave indie rock? With “Shitloads of Money,” it’s like you wanted to start scaring people off.

Not really. If you listen to Girly-Sound, what do you hear? The songs are ridiculous. They’re talking about money, about spending, about pop culture. The inconvenient truth, which no one wants to deal with, is that I was that person when I was doing Girly-Sound.

The anomaly was Guyville! My manager said, “I want to know why you change styles so much.” True me is me and a guitar. Anything else you put on it is an outfit, whether it’s an indie-rock outfit, a mainstream outfit, a plug-in outfit, a co-write outfit … Maybe I’m a little bit too adventurous for my own branding good. But that’s what you fucking pay us for! This is what kills me. You pay us because we create realities for you. We create visions. And no one ever claps for that. They want it to be confessional, like it just dropped out of my ass. I should be paid for my ability to create what doesn’t exist — that’s what I’m really good at.

When we consider your career as a whole, would it make sense to forget about music and consider you like you’re a visual artist?

I think like a visual artist, but I’m aurally heavy — a lot of my information about the world comes in through my ears, probably because I had very bad eyesight when I was young and had to sonar my way around.

You need three things in art. It needs to be true to your soul. It needs to be resonant in the greater culture so a lot of people feel it. And it has to show a window into a future realm — to punch a hole so we can follow into a new way. Those are the things I’m always searching for and failing to find, most of the time.

People talk about your two Capitol albums as sellouts. Did it at least work? Did you get paid?

I got a big check when Matador signed to Atlantic. And then when they went to Capitol, I got another big check. I made a good chunk off touring Liz Phair, which was hard-earned. I think it’s impressive that I’ve been able to keep a career going.

Haven’t you ever had the experience, as a fan, of hearing your favorite band change styles and make an album you hate?

Yeah. Skip that one. Go to the next band. It’s no big deal. If you invested so much of your identity in someone else, you’re not doing enough work on your identity. You’re giving away too much power to a band.

I feel like we’re talking around Meghan O’Rourke’s 2003 review of Liz Phair.

Yeah. The [review that called me a] sellout. She pissed me off because I thought she was taking cheap shots at me as a woman. I don’t believe that even if I were 70 and wearing something hot that there’s anything wrong with that. I want 70-year-olds to feel hot! You get a certain number of years on this planet, and you should have sex the whole time and party when you want.

What she did was like a real public shaming. [She said] it was shameful and I was a terrible mother for doing that. I say, give me more freedom while I’m here on this earth. Meghan ought to try wearing some hot clothes and having a good time. She might be happier. With record reviews, I don’t even mind, if you write it well. I’m kind of proud Pitchfork gave me a 0.0 for Liz Phair. But she was literally trying to shame me to not be sexual as a mother, and to make me feel sorry for trying to reach a broader audience.

Mim Udovitch wrote a Slate review that really summarized the reaction. She said the album didn’t represent “the artist that Liz Phair fans thought they knew.” People thought they knew you.

They didn’t. They never did. I think they do now. I’ve been more open, more myself. But you can’t have ownership over a band. I have never gotten mad at a band. Ever. I do not relate to that.

That album was the first to come out after your divorce and your move from Chicago to L.A. Was the move related to the divorce?

We both wanted to go to L.A. After we split up, I said, “If I moved, would you still go?” I couldn’t get enough work in Chicago. There’s a small sliver of pie, and if you get the pie, everyone hates you because they didn’t get the pie. And L.A. has so much pie!

I want to ask about your son, Nick, without being too intrusive about him, and —

He gets so mad at me! He goes ballistic.

You wrote “Little Digger” about him, which is one of the most heartbreaking parenting and divorce songs I’ve ever heard. In the song, you worry whether he’ll be okay. Is he?

[Sighs.] Who knows? He’s gone through some things that were difficult. I expect that when he’s older, he’ll air some of the dirty laundry and say some things that may not be flattering about me. He’s going to be okay, I think.

He’s proud of that song. But we don’t talk about it — in his world, I’m strictly mom.

Did becoming a mom change the way you thought about your music?

It did for a while. You’re listening to different stuff, you’ve got Teletubbies on the television, and that converged with the pop period.

I’d been very self-involved. Oh, you don’t understand what a burden it is that I got successful when I was young. I had all this angst about it. When I became a mother, I had a totally different perspective. I realized it was ridiculous: Oh, you poor thing. Your job is to get up onstage and sing, and people clap for you.

Did motherhood make you more artistically conservative?

No. I think “H.W.C.” came in that period. Instead of complaining about life, I got more positive, I hate to say.

When you were a teenager, who was your “Liz Phair”?

David Bowie, who changed all the time. He always was, and still is.

Bowie is still in the back of your mind?

Sometimes. I just tried to do some Modern Lovers–y songs. I enjoyed going into Jonathan Richman territory. His style of lyricism requires you to say the most embarrassing thing you can about yourself. I’m gonna use him as a muse. All the record labels heard the new songs and were like, “That doesn’t sound like Guyville.”

People literally said that to you?

They say it all the time. For 25 years.

Do you ever feel like, “Fuck Guyville”?

No, because arguably my whole career is anchored by that record. But in the first ten years, I had a sense of being trapped by it, and fleeing from it. I suffer from moderate claustrophobia. Crowds are hard — I don’t like being hemmed in. We were in a traffic jam going to see a show at the Greek [Theatre], and I got out of the car and walked. There’s always an exit strategy in my mind.

I was a sophisticated visual artist before I made Guyville. I was working for Leon Golub and Nancy Spero in New York, and Ed Paschke in Chicago. I was really talented. I was doing big, black charcoals about disease and identity. And when I got locked into this Guyville thing, I felt like, Fuck, it’s a trap. Until Liz Phair, I was trying to get out. I will gnaw my own foot off to get out of any kind of trap.

I grew up in fucking Winnetka, the preppiest suburb imaginable, and then suddenly I was identified with this downtown Wicker Park scene. Really? I’m going to cleave off an entire part of myself and live in a world that isn’t even mine? Exile in Guyville. Exile! Guyville was not my home. I wrote the whole fucking record about having trouble living in Guyville, and then Guyville became my home forever? No.

Guyville fans want you to live in Guyville?

Tough shit. And I’m not living in Winnetka either.

There’s now a generation of young indie-rock women who admire or emulate Guyville. Does that give you a sense that the world is changing, and you played a part in it?

I think I have played a part. It was always my aim to … This is a hard interview. The trouble at home was something I couldn’t talk about, and I still don’t want to. But I want people to say what’s hard and what’s hurtful for them. I want women to feel like they’re not sluts if they want to have sex, and they don’t want it with everyone if they say they want it sometimes. I wanted to change the world in certain ways, mostly for women and largely for myself.

To be my age now, 52, and see a huge music community of women that didn’t exist when I was coming up is the best fucking thing. If I meant something to them, they mean a hell of a lot to me. It’s why I want to get back out there. My “Liz Phair” now are these young women. They give me motivation, excitement, a sense of safety, and inspiration. Every day I follow a new female artist on Twitter, so I have more of that feeling I was so hungry for back then. Girlville is here.

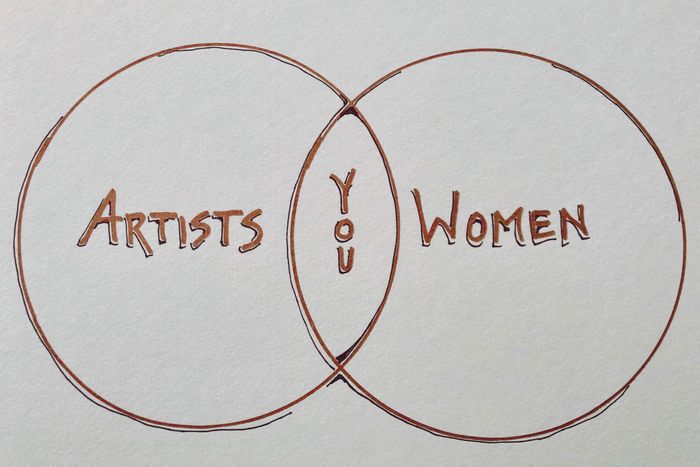

Do you have a piece of paper? I saw this Venn diagram on a young woman’s Twitter page, the header.

[Phair draws an illustration on a piece of paper.]

I want that on my epitaph. It’s the fucking story of my life. That’s the loneliness I live with, at all times. But all of a sudden I can see them.

One thing I’ve never read you talk about is the period after you graduated from Oberlin and before you moved back to Chicago, when you lived in San Francisco for a while. What did you do there?

I burned through all my savings from summer jobs in three-quarters of a year. I lived in a SoMa loft with my friend Nora Maccoby. Chris Brokaw, who I knew from Oberlin because his band Pay the Man was so good, came to visit Nora. She bugged out, so he and I hung out together. He said, “Record your songs. Send them just to me, not to anyone else.”

We did everything wrong in San Francisco. We partied all day long. We’d go out and try to get men to buy us lunches and dinners. We had three outfit changes a day. We’d be high for most of the day, or looking for weed. It was amazing. We tried to do everything on the cheap, so we’d go to a club and tempt men that we would date them, and then not date them.

Why did you leave?

I ran out of money and moved back home. Get your shit together. Get a job. I sold my art to people for $300 apiece. I had a safety net — I could go home and do laundry — but not much of one. My parents were fed up with the dilettante lifestyle I was leading.

I was 22 when I graduated college, and 24 when I made Guyville. It felt like a long time — a two-year period of aimlessness and temp work, desperately poor, mooching off everybody.

Where did you make the Girly-Sound cassette tapes?

It happened over the course of a year. I was desperate to get out of the house, and I would house-sit for friends of my parents who were on vacation — water their plants, walk their cat, or whatever it was, in exchange for the ability to set up a little home [recording] studio. I’d just spend all day recording these songs, with maybe a Scotch sitting next to me on the floor.

Did you tell anyone you were making music?

No, not at all. It’s ironic that now I’m known for being frank and open — my whole career started because I was the opposite of that. I played guitar and wrote songs for years, and would never perform them in front of other people. Maybe that’s why my style is so, what’s the word? Exposing.

In the “Surf Therapy” chapter of Horror Stories, you talk about being in love with a guy you call Rory, who wants to marry you, but suddenly confesses that he’s just had a kid with another woman. And you write that you were unable to date for ten years after that. When was that?

That was ten years ago. I date, but I’ve had trouble getting into a solid relationship. I’ve been a serial monogamist my entire life. But the older I get, the harder it is to find a match.

Why?

They either like “Liz Phair” and are disappointed by the normal suburban girl, or they like the suburban girl and then are a little threatened by “Liz Phair.” It’s hard to get someone who wants both. I’ll tell you one thing, I’ll die a cat lady before I ever get in another relationship with someone who’s threatened by my ambition.

There’s also a chapter in your book about having an affair while you were married. How does that square up with the part of you that’s private?

I had a lot of qualms about that chapter. I’d been working on some music. After Prince died, and Bowie, and even Tom Petty, my manager said, “If this were the last record you ever made, would you want to put it out?” I realized instantly, no.

Right after the Rory episode, I was paralyzed in life. Just crying every night. And I read the Jonathan Tropper book This Is Where I Leave You. He talks about his wife leaving him, and how it felt like a gunshot. That was one of the things that pulled me back to the living. Honesty saves lives. I’ve been saved so many times by other people’s honesty. And I wanted to be that. I wanted to contribute.

What’s happening in the Whitechocolatespaceegg song “Only Son”?

That’s brother. I’m writing from the point of view of my brother. “Table for One” is also written from his point of view.

The things he expresses in “Table for One” about being adopted — are those also your feelings?

They must be. I don’t think he’s spent as much time thinking about it as I have. We come from the same adoption agency — we’re not related [by blood]. A lot of my problems and his stem from being adopted. There’s a testing of boundaries, like, “Will you love me even if I’m bad?” There’s insecure attachment — you’re always expecting someone will give you away.

How awful.

It is hard. My parents loved us to within an inch of our lives. We had a secure and stable household. We were the disruptive elements. Mom and dad have it dialed in, which can give you a bad complex. You’re like, “What’s wrong with me that I can’t replicate this nice life?”

And you’ve still never tried to find your birth parents?

No. I have enough people I love, never mind a whole other family I have to check in on. If I could peep into their lives and learn all about them without an interaction, I’d do that instantly. I’m very curious. But I’m not ready, and probably never will be, to interact with them.

You don’t think meeting them could help you resolve some issues?

No. Those things formed very young. Having been a mother, if a baby is put into a nice, little warming place and the parent isn’t there for a week or two weeks, that’s a hell of a developmental thing right there. Are you a parent?

I am.

So you know about those first two weeks of bonding. Even if a nurse holds you, it’s always a different nurse and they don’t hold you all that often. And I didn’t get that bonding. I just sat by myself. I think that does something.

It also makes me search for who I am. What is love supposed to feel like? What is healthy love? It made me sensitive to the deeper questions because the trauma was probably deep. Who knows, if I had been raised by my birth parents, what kind of a life I would have had?