I was adopted in 1961 and brought up in a suburban house in a suburban street in the north of Glasgow. A small, semi-detached Wimpey house. Outside our house is a cherry-blossom tree that is as old as me. It doesn’t seem the most likely place to be introduced to the blues, but then blues travel to wherever the blues lovers go. In my street and in the neighbouring streets to Brackenbrae Avenue, I never saw another black person. There was my brother and me. That was it. The butcher, the baker and the candlestick-maker were all white. (Although I never actually met a candlestick-maker – has anyone?)

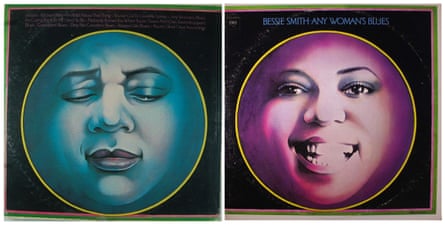

So the first time I saw Bessie Smith, it really was like finding a friend. I saw her before I heard her. My father – a Scottish communist who loved the blues – bought me my first double album. I was 12. The album was called Bessie Smith: Any Woman’s Blues and produced by CBS Records ( John Hammond and Chris Albertson; Albertson went on to write her biography). I remember taking the album off him and poring over it, examining it for every detail. Her image on the cover captivated me. She looked so familiar. She looked like somebody I already knew in my heart of hearts. I stared at the image of her, trying to recall who it was she reminded me of.

She looked so sorrowful and so strong. She would stand up for herself, so she would. She wouldn’t take any insults from people. I could see from her eyes that she was a fighter. I put her down and I picked her up. I stroked her proud, defiant cheeks. I ran my fingers across her angry eyebrows. I soothed her. Sometimes I felt shy staring at her, as if she was somehow able to see me looking. On the front cover she was smiling. Every feature of her face lit up by a huge grin bursting with personality. Her eyes full of hilarity. Her wide mouth full of laughing teeth. On the back she was sad. Her mouth shut. Eyes closed. Eyebrows furrowed. The album cover was like a strange two-sided coin. The two faces of Bessie Smith. I knew from that first album that I had made a friend for life. I would never forget her.

The names of the blues songs transported me places, created scenes and visions: Jail House Blues, Haunted House Blues, Eavesdropper’s Blues, Graveyard Dream Blues, Whoa, Tillie, Take Your Time, St Louis Gal, New Orleans Hop Scop Blues, Kitchen Man, Chicago Bound Blues, Worn Out Papa Blues. Each name was enough to make up a story. That’s what I liked about the blues, they told stories. The opposite of fairy tales; these were grimy, real, appalling tragedies. There were people dying in the blues; people coming back to haunt the people who were living in the blues; there were bad men in the blues; there were wild women in the blues. People travelled places, or wished they were someplace else in the blues. Could I be a St Louis Gal? Or could I be Tillie? Might Chicago be a place I would go when I grew up? Was the New Orleans Hop Scop like hopscotch? There were Daddys and Mamas galore in the blues. Every next person was a Mama or a Daddy but they didn’t sound like my mum and dad. “Mistreating Daddy, mistreating Mama all the time.” People got drunk and ate pigs’ feet in the blues. It was totally wild.

We had an old-fashioned record player that looked as if it was pretending to be a bit of furniture until you lifted its lid and saw its strange black arm and needle. I’d place the record down into the player, lift the arm of the needle and try and get it on the exact line of my favourite track. Sometimes I’d miss and hear the end of another unfamiliar track that would, for a moment, make me want to listen to it. I liked the way the piano and the horn sounded comical, as if they weren’t taking any of this so seriously. Especially in songs like Cemetery Blues and Graveyard Dream Blues; the musical accompaniment sounded like it was all one big joke, like the funny music in silent movies.

My favourite of the lot was Dirty No-Gooder’s Blues. It sounded so bad. The very name made you think things you weren’t supposed to be thinking at that age. A Dirty No-Gooder? What was he? Some man that said filthy words and had no morals. Some man who could not be good; some man who dedicated his whole life to being bad. I found the blues so exciting because the characters were real “characters”; people who behaved badly, who did terrible things, who killed and murdered and went to prison and missed Chicago and wanted to “Take it right back to the place where you got it”, whatever the “it” was. The men in the blues were lowdown and rotten, cheating and lying and lazy.

There’s nineteen men living in my neighbourhood.

There’s nineteen men living in my neighbourhood.

Eighteen of them are fools and the one ain’t no doggone good.Dirty No-Gooder’s Blues

At the age of 12 in my small suburban neighbourhood, the idea of describing men in this way was scandalous, hilarious. Mr Aird, Mr Tweedie, Mr Dunsmore, Mr Macintosh, Mr Murray, Mr Kerr, Mr Cochrane. Which one was no doggone good? Whenever I listened to the lyrics of the blues they made me feel I was being entrusted with a secret. I was being told a secret story about some no-good, no-count man. The story was for me and not for him. The story was a joke on him. Bessie Smith was singing for women. It was women who were singing those blues and the lyrics were mainly about the 101 ways a man could let you down. I guess I took the warning. Every woman could understand the blues. That’s why this album was called Any Woman’s Blues.

I realised that I could choose always to have Bessie Smith in my life, that she was not going to betray me or go off with another friend, or move to Kirkintilloch, or suddenly turn nasty. Nobody could take her away from me. And when I grew up and went away, I could take her with me. And I did. Hours and hours looking at her face on the cover and many hours memorising the lyrics to the songs. They weren’t all blues; some were vaudeville, some were Tin Pan Alley. But everything Bessie Smith sang sounded like a blues song. I had my favourite songs that I would play over and over again. ‘Kitchen Man’, ‘Dirty No-Gooder’s Blues’, ‘I’m Wild About That Thing’, ‘He’s Got Me Goin”.

Got me goin’

He’s got me goin’

But I don’t know where I’m headed for!

When I listened to the songs on this first album, I always assumed they were about Bessie Smith’s own life. (It didn’t occur to me to think this of folk, soul or rock singers.) The blues sounded like autobiography, like ordinary people telling the story of their lives. There was always an I in the blues. It was all first person. When I listened to Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out and Wasted Life Blues, I felt so sad for Bessie Smith. I could picture her whole life suddenly changing. (Her whole life did change, strangely mirroring Nobody Knows You; she might as well have been singing about herself.) I felt so passionate about her, it made me angry. I’d listen to the lyrics of her songs and that voice of hers that no other voice can ever come near:

Nobody knows you

When you’re down and out.

In my pocket, not one penny

And my friends, I haven’t any,

But if I ever get on my feet again

Then I’ll meet my long-lost friend.

It’s mighty strange without a doubt

Nobody knows you when you’re down and out,

I mean when you’re down and out.

I’d imagine her, wandering through the streets of segregated America, penniless, friendless. Down and out. There were many down-and-outs in Glasgow on Sauchiehall Street on a Saturday night. If nobody loved Bessie Smith when she was down and out, then nobody would love me. All that was left then would be to dream of death. Graveyard Dream Blues. Cemetery Blues. Wasted Life Blues. Somehow being down and out in America seemed to be inextricably linked with her colour. I could not separate them. I could not separate myself. I am the same colour as she is, I thought to myself, electrified. I am the same colour as Bessie Smith. I am not the same colour as my mother, my father, my grandmother, my grandfather, my friends, my doctor, my dentist, my butcher, my teacher, my headmaster, my next-door neighbour, my aunt, my uncle, my mother’s friends, my father’s friends. The shock of not being like everyone else; the shock of my own reflection came with the blues. My own face in the mirror was not the face I had in my head.

There were cheeky songs too on this double album. I’m Wild About That Thing – which contained the enigmatic line “I like your ting-a-ling”. (I couldn’t understand what was going on but it sounded sexual. Children approaching adolescence are adept at picking up on any hint of sex anywhere. And in the blues, it wasn’t so much a hint as a wallop.) There were the songs of defiance, of not putting up with it: “Take it right back to the place where you got it. I don’t want a bit of it in here.” I feasted off those songs for years. It was ages before I got another album so this one was it. It is still my favourite. The first love. The first time I heard her voice it made me wonder what I was remembering. Her voice was so raw and fresh and different from any other singing voice I’d ever heard. It was not like the voice of Gallagher or Lyle. It was not like Lena Zavaroni or Joni Mitchell, Rod Stewart or the Bay City Rollers. It was not Simon or Garfunkel. It was not Donny Osmond or David Cassidy. It was not Lulu or Elton John. It wasn’t even like the voice of Ella Fitzgerald, who I heard live at the Kelvin Hall in Glasgow when I was 14 with Count Basie accompanying her. No, Ella Fitzgerald’s voice had a girlish chuckle in it. Bessie Smith’s raw, unplugged voice dragged you right down to a place you had never been. It seemed to drag you down to the depths of yourself. Her voice carried a kind of knowing that made you feel this woman knew everything about life and was not frightened of any of it. It made me stop reading Anne of Green Gables and look up sharp and listen.

What was it I was remembering? Her voice made me want to be her. I could never listen to her as background music; I still can’t. In the days when she performed live, people were mesmerised by her. They would not be distracted or try to do anything else while Bessie Smith was on. She captivated them. She had them under her spell. It is still like that even just listening to her. You listen so hard she practically inhabits you; her very soul seems to find a way inside you. I’d try to move my lips the way I imagined she moved her lips. I’d wonder if she was ever called “Rubber lips” like I was. What would she have said? She would have fought anybody who called her names. I was certain of this. She wouldn’t have stood for it. “I won’t have a bit of it in here.”

My mind would wander off to her life. I’d picture her on the road travelling from small southern town to small southern town. I had read all about segregation, how black people were not allowed to sit on the same bit of the bus as white people, how they had to use different roadside restaurants, how they couldn’t sit down in ice-cream parlours. When I listened to Bessie singing Kitchen Man, I pictured her living in a small wooden house with a porch. I could see the Kitchen Man himself, a black man with a white hat. One of those tall hats that scare small children. He would be out the back baking, flour on his fists. He’d bring her plate after plate of those sweet jelly rolls. She just lay on her bed, dressed up in her feathers and plumes, and said, “Thank you Honey,” and tucked in to those goodies. I was a bit nonplussed when I discovered that all those jelly rolls and sugar rolls in those songs had nothing to do with food.

What was it she reminded me of? Whenever I impersonated her in front of my mirror with my hairbrush microphone, I had a sense of something, at the edge of myself, that I mostly ignored; the first awareness of myself being black. I’d only ever think about it if something reminded me. Bessie Smith always reminded me. I am the same colour as Bessie Smith. I’d look at her hands then I’d look at my own hands. I’d look at her nose then I’d look at my own nose. Perhaps she is related after all. Maybe my great-great-grandmother was a blues singer. Who knows?

The great thing about being adopted was that you could invent your family all the time. You could make them up and invent yourself in the process. At one point, every time I saw Shirley Bassey on the telly singing Goldfinger, I was convinced she was my birth mother. Any time I came across a black person – usually on TV, or in a book, or on a political poster that my father brought home – I tried to work out their relationship to me. I concocted an imaginary black family for myself through images that I had available to me. There were a lot of images in this politically internationalist household. Nelson Mandela, Angela Davis, the Soledad Brothers, Cassius Clay, Count Basie, Duke Ellington.

I liked trying to connect one black person to another, a racial jigsaw puzzle. I was aware that racial discrimination existed all over the world. South Africa had 16 legal definitions of black; South Africa had borrowed its system of apartheid from the American south. At Christmas time, I would sit down with my mum and send cards to the political prisoners in South Africa. All black people could at some point in their life face racism or racialism (I could never understand the difference) therefore all black people had a common bond. It was like sharing blood.

I did not think that Bessie Smith only belonged to African Americans or that Nelson Mandela belonged to South Africans. I could not think like that because I knew then of no black Scottish heroes that I could claim for my own. I reached out and claimed Bessie.

When I was a young girl, Bessie Smith comforted me, told me I was not alone, kept me company. I could imagine her life as I invented my own; I would not have grown up in the same way without her. Just at that crucial moment, before my periods, after my first bra, before I had any big romance, before I went to secondary school, there she was. It was perfect timing. I was just the right age for her to become my lifelong friend, my beautiful flame, my brave heartthrob, my paragon of virtue. My libidinous, raunchy, fearless blueswoman. My righteous, courageous, wild blueswoman. I am still full of her passion. I have her spark in my eye. I can burn with love, burn with the blues. I am still totally, utterly, Wild About That Thing.

I heard the singing of the Mississippi when Abe Lincoln went down to New Orleans,

and I’ve seen its muddy bosom turn all golden in the sunset.I’ve known rivers:

Ancient, dusky rivers.My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

Langston Hughes, The Negro Speaks of Rivers

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion