Jeff Buckley had released two live EPs (Live at Sin-é in 1993 and Live from the Bataclan in 1995) plus one complete studio album (Grace in 1994) before he died in 1997. Since his death, eight live albums and multiple compilation albums have been released, spanning music recorded while he was signed to Sony and also before he had a record deal.

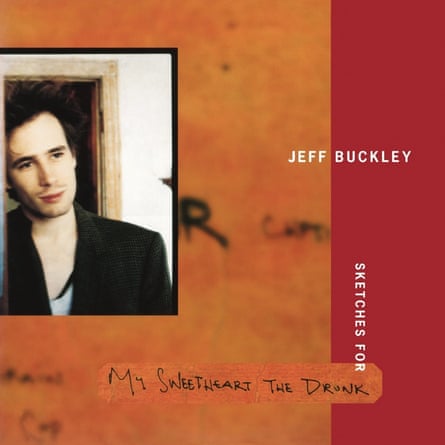

The most contentious is Sketches for My Sweetheart the Drunk, which was released a year after his death. Buckley had already scrapped a batch of recordings produced by Tom Verlaine in late 1996 and early 1997 and was preparing to record afresh in Memphis, the place where he drowned in the Mississippi.

Buckley left no will but his estate transferred automatically to his mother, Mary Guibert. While still mourning the loss of her son, she was informed that Sony was going to press ahead with the release of the Verlaine tapes under the title of My Sweetheart the Drunk (Buckley’s working title for what was going to be his second album) only a matter of months after his death. She had not, she claims, been consulted on this release.

“We found Jeff’s body and we had the two memorial ceremonies in July and August,” she says. “I went home and then I started to get calls from the band members saying, ‘Why are you going ahead with the album? Jeff never wanted those things! He wanted the [Tom] Verlaine tapes burned and blah, blah, blah.’ And I’m going, ‘Whoa, wait, nobody’s doing anything!’ I picked up the phone and I called the label. ‘Oh yeah, Steve Berkowitz [the Sony executive who signed Buckley] and Andy [Wallace, producer of Grace] are in the studio mixing and mastering.’ What? What the fuck is that? Well, that turned out to be the first CD. Oh yeah, that was ready. It was going to go into production.”

She instructed Conrad Rippy, her lawyer, to contact Sony to halt the release of the Tom Verlaine recordings. “They had put that album on the release schedule for fall 1997,” says Rippy of Sony’s plans. “Jeff and the band – and therefore Mary – were quite clear that the band was flying into Memphis to record the album that would then replace that album [the Verlaine recordings]. So for Sony just to slap it on the release schedule … I understand it as a business decision, you know, to capitalise [on it]. Literally the first thing I did was dictate a cease-and-desist letter to Sony. Which always gets their attention!”

Guibert says she and Rippy went to meet the senior executives at Sony to work out what, if anything, should be done with Buckley’s unreleased recordings. Grace was significantly unrecouped, and Sony was keen to get new product in the market; Guibert was less keen. The meeting included Don Ienner, chairman of the Sony Music Label Group, and he spoke privately with Guibert about what they should do. “I said, ‘I want one thing,’” she recalls of that conversation. “‘I want one thing. Just give me control and we’ll do it all together. You’ll be able to use everything you’ve got – that’s worth using.’” She puts extra emphasis on the words “worth using”. This led to a standoff with Berkowitz. Guibert accused him of working on the unreleased recordings “behind my back” as he “thought he was going to be the new producer of Jeff’s work”. A compromise was reached where it became a double-disc release with the Verlaine recordings on one disc and the more recent demos on the other.

Guibert says that she was adamant that Sony could not polish up the four-track demos and that they should be released as they were on the double album. “I said, ‘No! Listen! I know what you want to do. This is what you would do with his remains – put him in an Armani suit and some shiny shoes and comb his hair and put lipstick on him or something. That’s not who he is. These are his true remains – just as they are. Just treat them as if they were his true remains. If this was his body here and we were preparing it for his funeral, we would not put him in a suit. We would put him in a flower shirt and some black jeans and his Doc Martens and leave his hair all mussed up. And maybe a little mustard on his chin. We would not screw this stuff up by putting something out he would not approve of. So I won that argument.”

Relations with Berkowitz were so strained as to be deemed unsalvageable by Guibert. She felt betrayed by him (claiming he referred to her as “the bitch”) and was also offended that he was trying to be the one who defined her son’s legacy. To appease Guibert, Berkowitz was taken off all Jeff Buckley projects at Sony and replaced by Don DeVito, the producer and executive who worked with Bob Dylan, luring him back to Sony/Columbia in 1975 after his brief defection to Asylum and producing his 1976 album Desire as well as being the A&R contact for major names like Bruce Springsteen, Carole King and Billy Joel.

“Sony needed to move in someone else who had no agenda in releasing [Sketches for] My Sweetheart the Drunk in fall 1997,” says Rippy. “So they moved Don in quite quickly to help smooth the waters. Don ran the Buckley project with Mary for probably the next 10 years. Don and Mary developed a real collaborative partnership. That, especially in the earlier days of the releases, was essential to making sure that everything that came out suited the legacy appropriately.”

He says there is a hard lesson to be learned here for label executives trying to overrule heads of estates, especially if they are family members. “Don came in because we wouldn’t deal with Steve after that,” says Rippy. “I have, in the 23 years I have dealt with Jeff’s legacy with Mary, maybe had one conversation with Steve Berkowitz at the very beginning. You don’t get very far with Mary by dismissing her.”

I approached Sony Music to respond to what both Guibert and Rippy said about the company’s behaviour around the album release. A spokesperson for the company declined to comment.

So, having a family member – especially one who has previously collaborated creatively with the artist in question – involved to take unfinished recordings to completion is possibly the best route. It’s the least likely to face accusations of desecration.