A 68-year-old Nebraska woman has become the second human in history to discover parasitic cattle worms wriggling around her eyeballs.

The cringy case—which surfaced just two years after the first case in Oregon—raises concern that the worms may be angling for an uprising in the United States.

In a recent report in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases, parasitologists at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention noted that the worm—Thelazia gulosa, aka the cattle eye worm—has been in the US since the 1940s. "The reasons for this species only now infecting humans remain obscure," they write. But "[t]hat a second human infection with T. gulosa has occurred within two years of the first suggest that this may represent an emerging zoonotic disease in the United States."T. gulosa is a parasitic nematode known to infest the eyes of cattle in the United States and Southern Canada, as well as Europe, Asia, and Australia. The worms move from eye to eye via face flies, aka Musca autumnalis, which feast on tears. Both the flies and the hitchhiking worms were introduced to the US immediately after World World II, and the infectious cycle began.

Generally, the worms' journey goes like this: worm larvae floating around an eyeball gets picked up by a fly while they're sucking down the tears of their victim. Those larvae grow and molt in the fly's tissues before reaching an infective stage. At that point, they migrate to the fly's mouth parts and wait to be delivered to a new eyeball. Once in a peeper, they prefer to hang out between the eyeball and the eyelid but can move around, causing scarring and other issues.

-

Adult Thelazia gulosa removed from the eye of a human, now on a person’s finger.

-

Adult female Thelazia gulosa removed from the surface of the eye of a human, showing intestine and egg-filled ovaries taking up the majority of the length of the body.

-

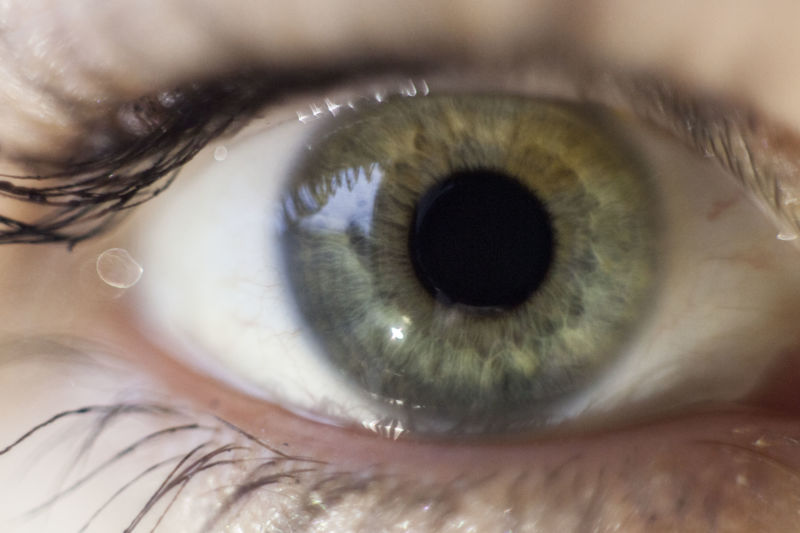

Thelazia gulosa in situ on the surface of a patient’s conjunctiva.

-

Thelazia life cycle.

In the latest human case, the Nebraska woman said her right eye became irritated and started bothering her in early March 2018. When she tried flushing it out with tap water, a squirming, transparent roundworm approximately 13mm long came out. She took a closer look at her eye and noticed a second one, which she then pulled out on her own.

The next day, she went to an eye doctor, who took out a third worm and sent it off to the CDC for identification. The doctor told her to continue pulling out worms she could see and gave the woman an antibiotic solution to prevent secondary bacterial infections. The woman's eye irritation continued, and later that month she saw another eye doctor and had an infectious disease consultation. Neither of the exams turned up additional worms.

But not long after the appointments, the woman flushed a fourth worm from her eye. After that, her symptoms resolved, and no more worms slithered out.

Infectious disease experts at the CDC suspect the woman picked up the infection while she was trail running in a regional park in Carmel Valley, California, which is where she spends her winters. She told the researchers that on one run, she remembered rounding a corner and colliding head-on with a swarm of small flies.

"She recalls swatting the flies from her face and spitting them out of her mouth," the CDC researchers reported. They also noted that the park is surrounded by cattle ranches.

In the first human case of T. gulosa—which occurred in a 26-year-old Oregon woman in August 2016—infectious disease experts think the victim may have just been too slow in swatting away a fly while she was fishing or horse riding earlier in the summer. In that case, the woman had a total of 14 worms extracted from her eye.

The CDC researchers call for monitoring of T. gulosa infections in animals as well as humans. Currently, there is no such monitoring, so there's no way of knowing if the worms are on the rise and will continue to show up in human eyeballs.

reader comments

92