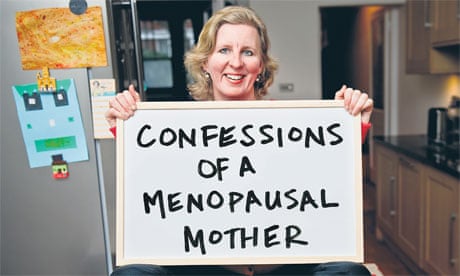

There's a new phrase in my lexicon, one I've hardly used in the last 20 years but one which is now, I'm surprised and even rather thrilled to report, tripping regularly off my tongue. In fact, I find I even quite enjoy using it. I like its irony; I like its cheek. But most of all, I like its central, ballsy sentiment. "I'm not available." That's the phrase. Sometimes I vary it a little. "I'm not currently available," I sing out, when they call for me; or "I'm not available now – try me later."

At first, I like to imagine, my use of this phrase was greeted by a horrified intake of collective breath around our family home. "Not available?" they must have repeated, eyes wide in shock, or perhaps frustration, or, at the very least, surprise. It was, after all, out of character; for two decades now, a motley collection of children have been shouting, from all corners of our house: "Mum/Mummy/Mother!". Followed, invariably, by some need, favour or requirement. "What's for tea?" "Do you know where my jeans are?" "Could you drive me to Elisa's/Molly's/Hannah's/Gabriella's house?" "Can I borrow a fiver?" "Have you seen my schoolbag?" "Can I use your mascara?" "Will you put my washing on?" Or any of the endless other tasks that have been hurtled in my direction dozens of times a day, hundreds of times a week, thousands of times a year and tens of thousands of times across two decades.

Now, though, I have my new response; and I don't just say the words – I mean them. I'm not available; not all the time, not any more. My four daughters, after all, are growing up. They are not babies: two are young women; another is on the brink of adolescence; even the youngest is thinking about secondary school.

But it isn't just my girls who have changed. Life feels different for me, too. All that warm, cosy, soft-round-the-edges oestrogen, the hormone that makes mothers revel in our role as chief nurturer and prime custodian of the next generation, has begun to ebb away. No longer do I feel that being a mother is my foremost occupation. Somewhere inside – and sometimes quite angrily – I have started to think that not only do I matter too, but that the time I have left to matter in is considerably reduced since the last time I felt I mattered, which was somewhere around 1992.

Don't misunderstand me – parenting has been the central plank of my life's work. No moment can surpass those four moments when I looked for the first time into a little face that had just emerged from inside my body; and, for me at least, mothering those children meant giving vast swaths of my life to feeding them and caring for them and looking out for them and smoothing the path for them. And, of course, that work isn't over yet, by a long way – it will go on in different forms for the rest of my life.

But as your babies grow older, you yourself are growing older too. And the bonds that bind you are, at least partly, hormonal: and at the perimenopause (which, at 48, I must surely be well into), those hormones weaken and the bonds loosen, and a mother like me suddenly thinks: hold on a minute! I am a person! I still have a life! And what she also thinks is: I'm not going to be always available any more.

So the menopause is a very dangerous moment in a family's existence. Because if society is built on the family unit, then that family unit is itself built on a mother's oestrogen. Her role as nest-builder, as tear-wiper, as meal-maker, as diary-keeper, as school liaison officer, as strategist, as trouble-shooter, as Jackie-of-all-trades and even (I hesitate to say it, but I believe that for most of us it's true at least some of the time) as doormat, is one of the cornerstones on which the nuclear family is constructed; and oestrogen, the hormone that courses through our veins throughout our childbearing years, is the lifeblood of our willingness to perform our tasks so selflessly.

So the depletion of that oestrogen throws at the very least a curve ball, and more often a hand-grenade, into an unsuspecting family. As the US psychiatrist Louann Brizendine puts it, in her book The Female Brain, the menopause is the moment when what she calls "the mommy brain" starts to unplug ... with sometimes-devastating effects. Women in their 50s are not only far more likely than younger women to initiate divorce proceedings ... they are also far more difficult and much more complicated to live with.

I say the family is unsuspecting because, at a time when so much in life is widely discussed and debated, the menopause remains, to a large extent, taboo. Even women themselves – including women of, to use that terrible euphemism, "a certain age" – keep schtum about it, as though by ignoring its existence they can somehow ward off its inevitability. And if women don't talk about it much among themselves, they certainly don't discuss it with their partners and children – and this despite the fact that their partners and children are going to suffer its consequences almost as much and possibly with more negativity than they themselves will.

No wonder then that online there's plenty of evidence of the shock, the confusion, and even the horror, families feel when the mother goes through the menopause. Message boards groan with the outpourings of children and husbands whose mother/partner has changed (overnight, it seems) into someone they describe, with unnecessary cruelty, as a psycho, a lunatic or a monster. No matter that the mother in their family has given 15, 20 or 25 years of her life to caring for their every whim, all they have noticed is that she's no longer doing it; and that is not only irksome and inconvenient – it hurts.

"My mum has changed overnight," says one poster. "She's gone nuts ... she raves at me about totally random stuff ..." "She gets snappy and irritable over stupid things," says another. "Her moods are completely unpredictable ... one moment she's cool as a cucumber, the next she wants to argue over nothing." "Our house is like a war zone," complains a third. "My mum behaves like a woman possessed ... nothing seems to get through to her any more."

It's a strange feeling for all concerned, this mummy-brain-unplugging. For years and years, I haven't been able to think of anything more fulfilling and divine than a cuddle with a daughter or the sight of a small child tucked up in bed, or a couple of little girls playing contentedly in our back garden. Now, though, I find myself snapping at my youngest daughter when she comes looking for a hug; I'm so tired all the time that I'm often in bed hours before them, so I never get to see them tucked up any more; and if the kids play out in the garden, the chances are that I'll be yelling at them for coming back into the house in their muddy boots.

It's still mothering, but it's not the fuzzy-focus mothering it used to be. And fortunately for me – and him – I already had a husband who's one of those grown-up kind of men ... because if he was of the overgrown toddler variety, the type who needs his food cooked and his clothes washed and who can't take his turn sorting out the children, I think this is the moment when our marriage would be on very shaky ground indeed.

Adding to the menopausal mix in our family, as in many others, is that my own hormonal volcano coincides with – and competes against – hormonal eruptions elsewhere. I sometimes wonder what our neighbours must make of the shouting matches that frequently ensue between a pubescent 12-year-old or a PMT-ridden 16-year-old and perimenopausal, 48-year-old me. I should spare our blushes, for all concerned, but put it this way: it's not pretty, it's not restrained, and it's certainly not quiet.

Yet, somewhere inside, I like to hope that all this angst and all these moods and all this rage might, just might, somehow be healthy. How so? Well, the reality is that my children have to grow up, like it or not (and children have a habit of not liking the reality of growing up very much, in my experience). Just as validly, I have to move beyond full-on mothering, and part of me is probably as resistant to that as my girls are to growing up. So perhaps, I sometimes muse, it's very clever that nature is calling time on the most intensive, and most time-consuming, phase of mothering, with this hormonal maelstrom. And it is calling time on it for my children, every bit as much as for me. "Grow up," I want to shriek, these days, when they ask me to make a dental appointment or do the shopping or cook a meal. "Grow up, and do it yourselves."

The miracle is that sometimes, unbelievably, they do. Well, no one has ever managed to phone the dentist but I find that if I hold out for up to a day at a time without producing a meal, one of them will eventually seize the initiative and cook supper. More exciting still, it is often rather good and a change from the same old recipes that I've been dishing up since the mid-90s. A bit of maternal revolution, you see, can actually pay off.

Another development is even more significant and more long-term. Because I sometimes feel that – through the slanging-matches, through the fighting, through the tears – my daughters (especially my elder daughters) and I are forging a new relationship, an adult-to-adult relationship, with one another. I am still their mother, but I feel they are more aware that I am also an individual, with needs and feelings, and even ambitions – not to mention hormones – of my own.

That matters, not just for me but for them, too – one day they will be 40-something, and one day they will also find that their child-rearing years are coming to an end.

At that point I want them to realise, as I am in the midst of realising myself, that there is life beyond all this, and that not only women but families too can adapt and change; and that, though this change is often painful, we can all come through it stronger and more fulfilled, and, I hope, just as happy as we were before.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion