In the Badwater Basin at the bottom of California’s Death Valley, the air feels like a giant hair dryer and the pavement can melt the soles of your shoes.

Yet on Monday night, 100 of the world’s top endurance runners set off on what has become known as “the world’s toughest foot race”, carving 135 miles of terrain through one of the planet’s most extreme climates at the most intense time of year.

Only 100 runners are selected from around the world each year to compete in the Badwater 135 Ultramarathon. Last year it was cancelled due to the pandemic – but this year the race was back on, even in the face of a historic drought and unprecedented heatwaves. On 9 July, Death Valley hit 130F (54.4C), the highest recorded in the valley – and on Earth – since 1913.

“We all think they’re a little crazy,” said Abby Wines, a spokesperson for Death Valley national park, “but we’re in awe of them as ultra-athletes.”

Wines watched the first wave of 33 runners leave the starting line at 8pm on Monday night. At that late hour, the big white digital thermometer in front of the park’s Furnace Creek Visitor Center read 110F but by the time the racers were finishing crossing the flat expanse of the valley Tuesday afternoon, temperatures were closer to 115F.

Wines said the competitors drew both admiration and head-shaking from the 145 hardy souls who live in the valley full time: “Even living here, we all struggle with the heat.”

‘Unlike any other race on earth’

Ultramarathoning has boomed in popularity in recent years but has also faced criticism for its dangers; in May this year, 21 ultramarathoners died in China amid extreme weather conditions.

But for many ultrarunners, it’s the sheer scale of the challenge that draws them to the Badwater race.

“It’s unlike any other race on Earth,” said Dean Karnazes, who has run the Badwater 11 times, dropping out only once after collapsing in the heat. “Not only is there the heat, but there is a ferocious headwind, like having a blow dryer in your face. Everyone runs on the white line, because the asphalt can melt your tennis shoes.”

Runners go to extreme lengths to prepare their bodies for the heat. For Karnazes, who did not race this year, that meant doing sit-ups and push-ups in the sauna at his gym. He’d also drive to Death Valley for the race wearing several layers of parkas with the heat in his car turned all the way up.

The race climbs from the lowest elevation in North America, at 280ft (85m) below sea level, to where the road ends on the way up Mount Whitney in the eastern Sierra Nevada Mountains, at 8,360ft.

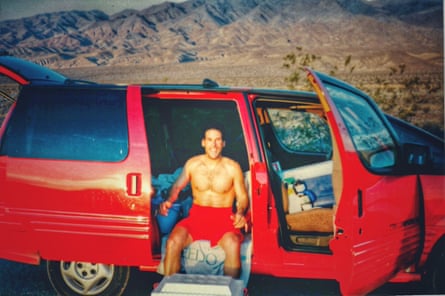

Each runner is trailed by their own support crew in an air-conditioned minivan, which leap-frogs their progress, stopping every few miles to provide them gushes of water from spray bottles, electrolytes, ice cubes, snacks and extra changes of shoes.

Race organizers also provide medical staff and are required by the park to provide their own ambulances. This is essential, Wines said, because the closest real emergency hospital is 125 miles away in Las Vegas and helicopters can’t fly in heat greater than 118F.

The park’s rangers get several calls a week to rescue visitors who are experiencing symptoms of heat illness, but the race has not produced any serious injuries, Wines added.

The race takes place over a 48-hour period. By Tuesday night, Harvey Lewis, a Cincinnati high school teacher and 10-time competitor, had won,clocking a time of 25 hours and 50 minutes through the course. A few hours later, the noted ultramarathon runner Sally McRae, 42, won the women’s division, crossing the finish line around 6am on Wednesday.

Though many international competitors were unable to travel for this year’s race due to the pandemic, the runners represented 17 countries and 29 states, including 24 women and 60 men, with entrants ranging in age from 28 to 76.

There is no prize money for the race, but those who finish in less than 48 hours receive a coveted Badwater 135 belt buckle.

“To even apply to enter the race, the runners have to have done a series of other tough ultra races,” said the race director, Chris Kostman, in an interview last week on Accuweather TV. He said a committee then studied the qualifications of each runner. “It’s much more detailed than applying to a college or getting a job, because our goal is to host a race with people who are capable of finishing the race.”

Making it to the finish line

Arnold Begay of Tulsa, 58, was attempting to finish the race for a second time, representing the Navajo Nation. On the podcast Run the Riot, he said his childhood living on an Arizona reservation with no electricity or water had given him the preparation he needed for this kind of event. But, he said, his first run of the course in 2009 had been much worse than he had ever expected.

“It was like my gut was torn out,” he said. “I took a beating. I have never experienced this kind of agony.”

But he said somehow, after working as a support crew member in the last race in 2019, he was drawn to do it again.

It appeared from the race stats that Begay dropped out some time after completing the first 42 miles nearly 12 hours into the race.

While Karnazes won the race in 2004, it is the many pitfalls and misadventures of the course he remembers most vividly.

“I don’t like to say I won, I just survived the fastest,” he said.

He remembers passing rattlesnakes, scorpions and tarantulas, who come to warm themselves on the road at night, and having his crew take his temperature and feed him whole chunks of ice to make sure his core temperature wasn’t shooting towards heatstroke.

He said that runners’ feet swelled so much, as they made their way through the heat and up the three major climbs of the relentless course, that competitors regularly carried several bigger shoe sizes so they could upsize during the race.

Runners often covered themselves head-to-toe in white, UV-resistant fabrics to avoid blistering, he said. Nevertheless, the glaring reflection of sun off the road could sunburn the inside of your nostrils or the roof of your mouth.

Karnazes, who wrote about the Badwater race in his book A Runner’s High, remembers the first time he ran the Badwater – and failed to finish – in 1995. The RV he had rented for his support crew had blown up and he had tried to go on by himself without help. He said the crew had eventually found him passed out on the roadway and had taken him to a hotel to revive him. He had woken up wondering why he wasn’t still in the race, but he was determined to come back and do it again and again.

“There’s magic in misery,” said Karnazes, who still runs ultramarathons but promised his family he would give up the grueling Badwater, after he ran his 10th race in 2013. He admits he’s still drawn by the sheer hell of it.

“I’m very tempted,” he said. “I’ll probably go back.”

Wines says the stamina of the runners is refreshing for park rangers who are used to people making extremely short summer visits to the park.

“In the summer, most people just drive through and take a picture of the thermometer,” Wines said. “They jump out of their air-conditioned cars, feel the heat and then get back in again. Which is fine, because regular people, who aren’t acclimated to the heat, shouldn’t push it.”

But, she said, these racers “are putting themselves up against the landscape at the most extreme time of the year, which is an admirable way of experiencing it”.