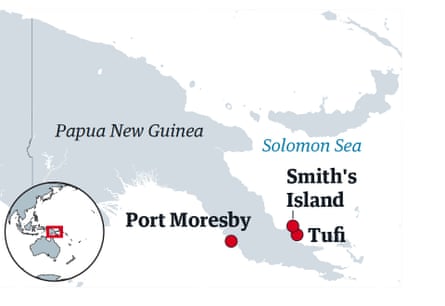

I’m sitting on a grassy slope at night with a man called Smith who is wearing warpaint. There’s a warm breeze blowing in from the Solomon Sea and starlight reflects from the waters of the fjord below. There is no artificial light at all. Even Smith’s mobile phone is dead since he can only charge it when he makes a four-hour paddle in his dugout canoe around the coast to Tufi, the nearest place with electricity and a town connected to the rest of Papua New Guinea only by the occasional visit of a light aircraft. A few fruit bats flap overhead, heading for Smith’s banana trees in the jungle.

“Your guests must think this is paradise,” I say to Smith, who is also wearing the ceremonial grass skirt he put on when he saw my kayak slowly progressing up the fjord from the sea.

He laughs and goes off to his hut to fetch something. It’s a visitors’ book. He hands it to me with a pen. “We have been open for 12 years,” he says.

I get my headtorch out and open the book. It is empty. Not a single entry. He shrugs. “I don’t know why, but people don’t come.”

With Covid-19 rampaging across the planet, hotels empty and their owners understandably anxious about what a few weeks of lockdown could mean, it’s sobering to think of a man like Smith. One day, 12 years before my arrival, he had been in Tufi and chanced upon the visit of representatives of a foreign NGO. Their message was simple: adapt your house to accept paying guests because there is a way out of your isolation: tourism. Wealthy outsiders will be fascinated to stay with you. The idea is called “homestay”.

Smith didn’t just adapt his house, he moved it. The family had been living in the deep jungle that cloaked the slopes of the mountains several days’ walk from Tufi. Now he spotted a beautiful small island in one of the Tufi peninsula’s many fjords. It was a tough paddle in a dugout canoe from the town, but Smith imagined foreigners must be taller and stronger than him, quite capable of meeting the challenge. On a little knoll with a particularly fine view down the jungle-fringed fjord, he built a small hut from palm leaves and bamboo. He set aside the ceremonial feathers and war paint required for a full-blown welcoming ceremony, instructed his wife, sister and mother in what to do, and then waited.

“And somebody came right away,” he says.

I point at the empty book. “I’m not the first?”

He explains that a Swedish man had arrived by kayak in the first week. “We were very pleased.”

The man stayed a week and suggested he get a visitors’ book. Smith declared that the man’s birthday would be an annual celebration. After this initial success, the family prepared themselves for an influx of outsiders. They are still waiting.

My own journey here hints at why this might be. I had flown on a small plane from PNG’s capital, Port Moresby, to Tufi, staying in a dive resort run by an amiable Kiwi couple. Tufi is on a peninsula that juts out from the feet of the Trafalgar mountains, a jagged, jungle-skirted skyline. Inaccessible by road – there are none – the peninsula is deeply indented by several long fjords, whose wild, jungly shores are sparsely inhabited by fishermen. The canoe is the main means of transport. Each fjord is a perfect little nursery for marine wildlife, although there are other things here too, like a second world war Jeep just off the jetty. The diving beyond the mouths of the fjords is epic: vast, colourful coral mountains jutting up from an indigo darkness haunted by sharks.

One evening in the resort’s bar, Brian, the manager, told me about Smith and his homestay. Brian had only recently arrived in Tufi and had never heard of anyone visiting Smith. He offered me a sea kayak and some directions. I accepted, and set off the next morning.

I didn’t get very far. At the mouth of the fjord, I realised the sea was too rough. By the time I got back to the jetty, I was feeling seasick and ready to give up, but Brian is an old-school Kiwi who doesn’t accept defeat easily. “Shove your kayak up on the launch, mate. I’ll give you a lift past the chop.”

An hour later, drenched and exhausted, I was dropped off in quieter seas. “See that entrance to a fjord over there?” he said. “Paddle through that gap in the reef and keep going. You can’t miss Smith’s Island.”

I headed towards the shore on my left. Close to the mangroves I came across a dugout canoe and two people: Aloysius and heavily tattooed Judy. He was in the water, looking for sea cucumbers. “We have a special variety that the Chinese traders pay a lot of money for.” He lifted one out of the canoe for me to see: a mottled, yellow, knobbly slug about the size of a draught excluder and probably almost as tasty.

Leaving the couple, I paddled onwards and soon spotted the island. There was a flurry of activity when I was spotted, and as I landed two warriors charged at me brandishing spears in my face and yelling terrifying curses. Then three women, garlanded in flowers, sang and danced.

Now, in a shady shelter where food is served, I admire Smith’s outfit. He identifies each bird that has given its feathers to make his costume. “We used to take seashells upriver and trade the feathers. This is cassowary – we didn’t kill them traditionally, but the Christians taught us that it’s OK.”

That night I sleep in the visitor’s palm hut, the thatch rustling in the warm sea breeze, starlight shimmering on the water. The island is about a square kilometre of steep-sided, grassy hills and patches of fruit trees dotted with the grass-roofed houses where Smith and his family live. His brother is also here.

We spend the next day paddling up the fjord and trekking through vibrant jungle to see some caves where the fruit bats hang out. Smith is talkative. He describes a homeland that, in the past, was torn apart by tribal wars. The jungle had been haunted by a “monster pig” and the sea ruled by a giant octopus. Many people still worshipped snakes, but also went to church. In this new world, people paddle all day to reach a shop with an internet connection, but their old world is always there in the shadows. Smith tells me how one tribe, defeated by another whose snake god was “too strong”, found themselves enslaved. Secretly, they kept their language and culture alive within the world of their masters. As the years rolled by, the masters forgot who was slave and who was not. The tribe within a tribe lived on, awaiting their chance. They were still waiting. “Like now we wait,” he chuckled. “For the tourists.”

Our canoe journey takes us through long tunnels of vegetation where strange scarlet flowers hang in the branches. Hornbills and cockatoos sit in the treetops, an avian reminder that this is Australasia with hints of south-east Asia.

Back at the island, before sunset, I swim around its rocky shores followed by various children who swim with the ease and fluidity of young seals. Smith’s wife, Ethel, gathers clams from their sea garden which we later eat.

After two nights I load my kayak and reluctantly say goodbye. Smith’s Island leaves me with the feeling that I’ve tasted something mysterious and sweet, like nothing I’ve come across before. As I paddle down the fjord, colourful birds flit through the jungle to my right. I think of Darwin’s Galapagos finches, isolated and remote, growing and evolving into something new, something different from anywhere else. Humans can be like that. For a man like Smith, isolation has activated his ingenuity and brought innovation.

On my return kayak trip I cope with the waves, staying inside the reef. The dive resort, which had seemed so remote after the plane ride, now feels like a busy modern metropolis. I head for the bar to find Brian. I’m going to tell him that Smith’s Island is amazing and he should send more guests. Smith’s isolation period has spun a magical web, one that I feel honoured to have experienced, but after 12 years he needs the world to come to him.

The trip was provided by Dive Worldwide, which offers a 14-day diving trip to Tufi, with homestay options like Smith’s Island. For further, information see papuanewguinea.travel