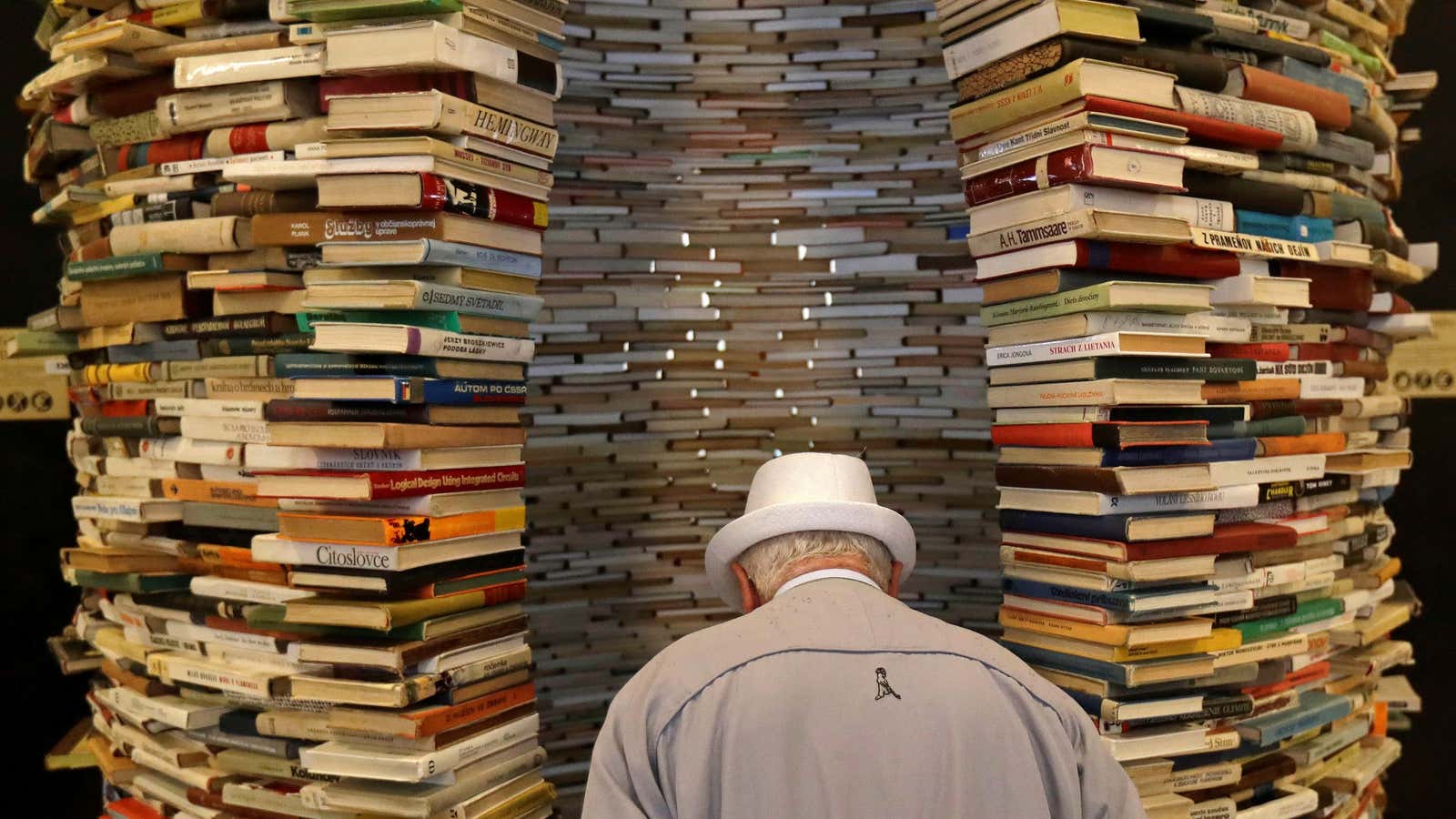

The books that get published often reveal a certain flavor of the age.

Before he hit the big time, horror writer Stephen King was rejected from a publisher on the grounds that “negative utopias” do not sell. (King’s dystopian books eventually sold in their millions.) In 2015, the success of French novelist Michel Hollebecq’s bestseller Submission was attributed by the New York Times to “French fears of terrorism, immigration and changing demographics.” Margaret Atwood’s The Testaments, tipped to be this year’s Booker Prize winner, has flourished commercially in a climate of increased consciousness around reproductive rights, gender politics, and the risks of autocracy.

Books reveal something broader about a country’s cultural mood. That, at least, is the logic underpinning a paper (paywall) recently published in the journal Nature Human Behaviour by the University of Warwick’ Thomas Hills, Daniel Sgroi, and Chanuki Illushka Seresinhe, and the University of Glasgow’s Eugenio Proto.

The researchers used digitized text from millions of volumes published since 1820 (via Google Books) to produce a quantitative analysis of trends in “historical subjective wellbeing” across the UK, the US, Italy, and Germany. If there was a “good old days,” they argue, perhaps it coincided with a spate of sunnier books getting the green light from publishers. This happiness index was compared with trends in GDP and lifespans over time to see how it tracked incomes and health. The findings were also corroborated with sentiment data drawn from an archive of British periodicals as well as two independent indexes measuring “National Pleasantness” and “National Polarity.”

A few trends emerged: as countries get richer, happiness—as measured by the book-based index—rises too, but only a little. People living an additional year, however, appears to make them as happy as a 4.3% increase in GDP.

But when were people actually happiest, according to their analysis?

In the UK, happiness seems to have peaked in the late 19th century, as Britain’s empire flourished and its economy boomed. (These findings are complicated by the fact that, at least in 1875, national literacy was around 75%: those unable to read may have been far less happy than the book-buying public.) Brits were most unhappy in the late 1970s, during a period often known as the “Winter of Discontent,” characterized by historic poor weather, trade union strikes, and soaring inflation.

In the US, the “good old days” seem to be right now: happiness has never been higher, as measured by the sorts of books being published (King and Atwood notwithstanding). It fell to its lowest point in the mid-1970s, around the time of the Vietnam war and the evacuation of Saigon.

Italy and Germany, meanwhile, are both in a period of relative dispassion. The book-based index suggests that happiness in Italy has been falling since about 2010, with a 150-year peak shortly after the new millennium. In the past century, German happiness was at its highest immediately following World War Two. The country’s reunification, in 1990, seems to have had only a minimal effect, if any, on the country’s national mood.

“Even temporary economic booms and busts have little long-term effect,” said Hills, in a statement. Whatever obstacles people may face—wars, revolution, depressions—they quickly return to a similar level of well-being, he explained. “Our national happiness is like an adjustable spanner that we open and close to calibrate our experiences against our recent past, with little lasting memory for the triumphs and tragedies of our age.”