Many know of the epic race in 1910 between Roald Amundsen and Robert Falcon Scott to be the first to reach the South Pole, and the tragic end met by the latter explorer.

Most people have also heard of the heroic leadership of Ernest Shackleton, who managed to save the lives of all of his men when their attempt to traverse Antarctica in 1914 went horribly awry.

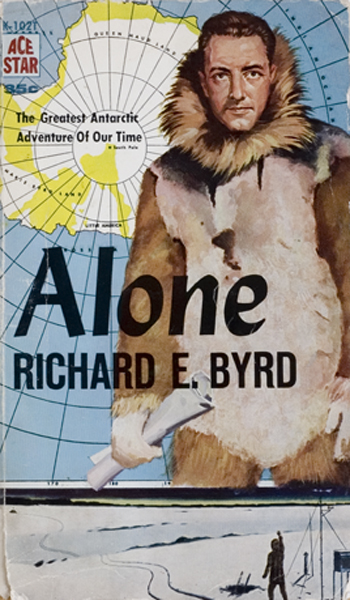

Fewer, however, are familiar with another tale of Antarctic adventure, that of the almost five months Rear Admiral Richard E. Byrd spent alone at the bottom of the world in 1934.

While Byrd was one of the most celebrated figures of his time (receiving an unprecedented three ticker tape parades), his fame has slipped beneath that of other polar explorers, perhaps because his adventure was of a strikingly different kind. Rather than involving teams of men, and sweeping treks across land and sea, Byrd didn’t travel with anyone else, or cover any geographic distance at all. Rather, he stayed, by himself, in exactly one place: a tiny shack buried under snow and ice. Yet while Byrd’s journey was not outward but inward, his expedition to the farthest reaches of solitude covered a significant amount of ground, circumscribing the spirit of man and his place in the universe.

Why Byrd Decided to Spend a Season of Solitude at the Bottom of the World

“it is something, I believe, that people beset by the complexities of modern life will understand instinctively. We are caught up in the winds that blow every which way. And in the hullabaloo the thinking man is driven to ponder where he is being blown and to long desperately for some quiet place where he can reason undisturbed and take inventory.” –Richard E. Byrd, Alone

By 1934, the “Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration” had drawn to a close. Much of the continent had been explored and mapped, and the pole had been attained through “manual” means (dog sled and skis) and ample struggle. As technology progressed, and the Heroic Age became the “Mechanical Age,” more territory was covered with increasing ease, and few polar “firsts” remained.

Byrd was a highly decorated naval officer and aviator; as a military pilot, the third man to fly non-stop over the Atlantic, and a polar explorer, he earned twenty-two citations and special commendations including the Medal of Honor, the Navy Distinguished Service Medal, the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Navy Cross, and the Lifesaving Medal (2X).

Of those that did, Byrd had already bagged the most prominent, acting as navigator on the first flights to reach the North and South Poles.

But as Byrd admits in his riveting, must-read memoir, Alone, despite these accomplishments, and the voluminous ticker tape which followed them, their aftermath still left him feeling a “certain aimlessness.” He not only longed to traverse another fresh frontier and tackle another daring, publicly-recognized challenge, but to address a certain restlessness he felt in his private, personal life — a niggling feeling that “centered on small but increasingly lamentable omissions”:

“For example, books. There was no end to the books that I was forever promising myself to read; but, when it came to reading them, I seemed never to have the time or the patience. With music, too, it was the same way; the love for it — and I suppose the indefinable need — was also there, but not the will or opportunity to interrupt the routine which most of us come to cherish as existence.

This was true of other matters: new ideas, new concepts, and new developments about which I knew little or nothing. It seemed a restricted way to live.”

To address these yearnings, Byrd came up with a plan that aimed to kill two birds with one stone: during the long, dark Antarctic winter, he would man, alone, “the first inland station ever occupied in the world’s southernmost continent.” While the rest of his expedition team remained at the Little America base along the coast of the Ross Ice Shelf, Byrd would set up camp at Bolling Advance Weather Base on Antarctica’s colder, even more barren interior.

The daring (some would say foolhardy) endeavor had an ostensible scientific purpose — that of making weather and celestial observations and gathering data. But Byrd admitted he “really wanted to go for the experience’s sake” — “to try a more rigorous existence than any I had known.”

The experience would certainly be physically rigorous.

Though Byrd would stay put in a shack buried under the snow, he would emerge through its trap door multiple times a day to take metrological readings, and would still have to survive in “the coldest cold on the face of the earth.” Temperatures would routinely hover around -60 outside and be subzero even inside: it would sometimes be -30 when Byrd arose from his bunk in the morning and the walls and ceiling of the hut would slowly become encased in a layer of ice. Should something go wrong, help was over 100 miles away, across a terrain that would be impossible to traverse in the trough of the Antarctic winter.

The psychological rigor of the experience, however, would be just as intense.

The lonely landscape would not only be cold, but lacking in light; once the sun sets during the Antarctic winter, it doesn’t rise again until the spring, ushering in a “long night as black as that on the dark side of the moon.”

As “perhaps the most isolated human on earth,” no other person, seen or unseen, would exist within a 123-mile radius, and Byrd’s only contact with the outside world would be intermittent radio exchanges he made with the men back at Little America; even in these communications, while Byrd would be able to hear the men at the other end, he would only be able to respond through international Morse code. Weeks would go by without him uttering a single word.

Existing in a “world [he] could span in four strides going one way and in three strides going the other,” Byrd would enjoy no external stimuli beyond his books, his phonograph, and what he could observe in the icy landscape. There would be almost no deviation in his daily routine for months on end; “Change in the sense that we know it, without which life is scarcely tolerable, would be nonexistent.”

Finally, the silence accompanying this solitary sojourn would be “taut and immense” — filled with the kind of “fatal emptiness that comes when an airplane engine cuts out abruptly in flight.”

Yet all these considerations made the plan more compelling to Byrd, not less:

“Out there on the South Polar barrier, in cold and darkness as complete as that of the Pleistocene, I should have time to catch up, to study and think and listen to the phonograph; and, for maybe seven months, remote from all but the simplest distractions, I should be able to live exactly as I chose, obedient to no necessities but those imposed by wind and cold, and to no man’s laws but my own.”

Byrd desired to “know that kind of experience to the full, to be by himself for a while and to taste peace and quiet and solitude long enough to find out how good they really are.”

During his stay at Latitude 80° 08′ South, Byrd got his wish, as well as much more than he bargained for.

What Byrd Discovered From Experiencing Five Months of Solitude at Latitude 80° 08’ South

“Yes, solitude is greater than I anticipated.” –Richard E. Byrd, Alone

While Byrd did not travel far on this expedition, the insights he garnered are in many ways more useful than those brought back from the far-flung treks of traditional explorers. They deal with the issues the everyday man faces — loneliness, isolation, unvarying routine, lack of change — writ large. Byrd’s challenge would be that of finding meaning in the mundane — the same challenge we all face, simply to a lesser degree.

During months of uninterrupted introspection and an intensity of voluntary solitude few humans have ever experienced, Byrd gleaned many insights on these issues. Here are some of the realizations he reached during his solitary sojourn at the bottom of the world:

We Need Less Than We Think

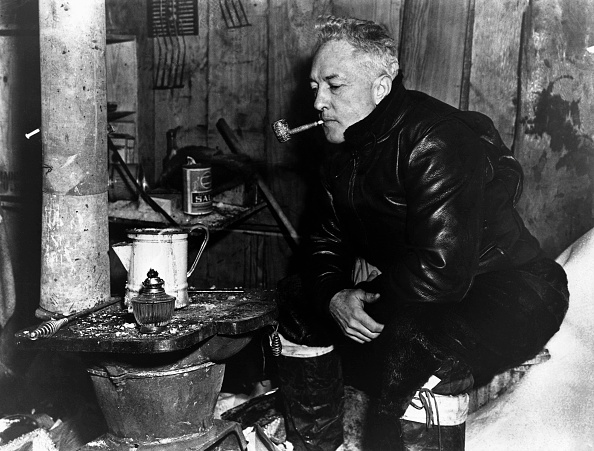

In 1947, Byrd revisited his hut at “Advanced Weather Base,” and picked up and smoked a pipe he had left behind 12 years earlier.

The overarching theme that runs through Byrd’s experience with solitude, is the way it helped him pare away the superfluous in order to focus on the truly important and meaningful:

“My sense of values is changing, and many things which before were in solution in my mind now seem to be crystallizing. I am better able to tell what in the world is wheat for me and what is chaff.”

As we’ll see, this sifting process would concern Byrd’s more abstract ideas and philosophy. But it would alter his views on material possessions as well.

Adjoining Byrd’s small shack were two snow tunnels that held an ample supply of all the provisions a man might need to survive by himself for half a year: candles, matches, flashlights, batteries, pencils and writing paper, laundry soap, food, etc. Yet beyond these essentials, along with a shelf of books and a box of phonograph records, Byrd had few of the creature comforts, conveniences, and entertainments that fill the abodes of most modern men. He had essentially one set of clothes, one chair, one little stove to cook food.

In taking stock of the distillation his existence had undergone, Byrd reflected:

“Yet, wasn’t this really enough? It occurred to me then that half the confusion in the world comes from not knowing how little we need.”

Being forced to live the simple life, Byrd decided, “was very good for me; I was learning what the philosophers have long been harping on — that a man can live profoundly without masses of things.”

Exercise Preserves Your Sanity

Despite frigid, potentially inertia-creating temperatures, Byrd got in bouts of exercise nearly every single day. (The next time you think it’s just “too cold” to go outside and move your body, remember this journal entry of Byrd’s: “It was clear and not too cold [today] — only 41 degrees below zero at noon.”) He felt his daily exercise helped preserve not only his physical health, but his mental health as well.

In the mornings, while the water for his tea heated up, Byrd would lie upon his bunk and do fifteen different stretching exercises. “The silence during these first few minutes of the day is always depressing,” he wrote in his journal, and “My exercises help to snap me out of this.”

Byrd also took 1-2 hour walks outside each day (which included doing a dozen different exercises along the way, like knee bends). These jaunts provided him with exercise, fresh air, and a change of scenery, as well as a great deal of mental repose and elevation:

“The last half of the walk is the best part of the day, the time when I am most nearly at peace with myself and circumstances. Thoughts of life and the nature of things flow smoothly, so smoothly and so naturally as to create an illusion that one is swimming harmoniously in the broad current of the cosmos. During this hour I undergo a sort of intellectual levitation, although my thinking is usually on earthy, practical matters.”

Much of Our Behavior is Externally Conditioned

“A man had no need of the world here — certainly not the world of commonplace manners and accustomed security.”

The longer Byrd spent isolated from the everyday world, the more he noticed the trappings of civilization falling away, and how “A life alone makes the need for external demonstration almost disappear”:

“Solitude is an excellent laboratory in which to observe the extent to which manners and habits are conditioned by others. My tables manners are atrocious — in this respect I’ve slipped back hundreds of years; in fact, I have no manners whatsoever.”

Byrd even observed that something like swearing, often assumed to be indulged in for one’s own benefit, was in fact largely performative:

“Now I seldom cuss, although at first I was quick to open fire at everything that trued my patience. Attending to the electrical circuit on the anemometer pole is no less cold than it was in the beginning; but I work in soundless torment, knowing that the night is vast and profanity can shock no one but myself.”

Byrd’s hair grew long and shaggy (he preferred to keep it that way, as it kept his neck warm). His nose became red and bulbous and his cheeks blistered from being nipped by hundreds of frostbites. Yet his increasingly barbarous and disheveled look did not bother him in the least, as he “decided that a man without women around him is a man without vanity.”

He shaved his beard “only because I have found that a beard is an infernal nuisance outside on the account of its tendency to ice up from the breath and freeze the face.” He did take a bath each evening, keeping himself quite clean, but he performed this ritual, he notes, not out of a sense of etiquette, but simply because it felt good and kept him comfortable. “How I look is no longer of the least importance,” he wrote in his journal, “all that matters is how I feel.”

Byrd found the process of reverting back to a more basic, “primitive” state interesting and instructive, musing, “I seem to remember reading in Epicurus that a man living alone lives the life of a wolf.”

It’s not that Byrd discovered that manners and other externally conditioned behaviors have no point and kept living like an uncultured barbarian after leaving Latitude 80° 08’ South; on the contrary, once back in the States, he returned to comporting himself as an officer and a gentleman. But he never forgot that civilization is an externally conditioned patina on a rawer way of life, and that much of how we act is a form of theater — a very useful form, but theater nonetheless.

There Is Peace and Power in a Daily Routine

“From the beginning I had recognized that an orderly, harmonious routine was the only lasting defense against my special circumstances.”

While Byrd discovered that a life lived in solitude offered many consolations, he was also very cognizant of its challenges. Mainly, that of being stalked by the incessant specter of desperate loneliness — a loneliness Byrd found “too big” to take “casually.” “I must not dwell on it,” he realized. “Otherwise I am undone.”

To keep the melancholy of isolation at bay, Byrd set about creating a busy, but orderly daily routine for himself. This was not an easy task, he admits, for he describes himself as “a somewhat casual person, governed by moods as often as by necessities.” Nonetheless, during his stay at Advance Base this “most unsystematic of mortals endeavored to be systematic,” as he saw the creation of set habits as vital to preserving his psychic equilibrium.

The keys of Byrd’s daily routine were two-fold.

First, he filled each day with maintenance jobs, always giving himself about an hour to work on each task. Regardless of whether he finished the job or not, once the sixty minutes were up, he turned to the next task, resolving to take up any unfinished work the next day. “In that way,” he explains, “I was able to show a little progress each day on all the important jobs, and at the same time keep from becoming bored with any one. This was a way of bringing variety into an existence.” As he further reflected, by keeping a schedule in this way:

“It brought me an extraordinary sense of command over myself and simultaneously freighted my simplest doings with significance. Without that or an equivalent, the days would have been without purpose; and without purpose they would have ended, as such days always end, in disintegration.”

The second key to the efficacy of Byrd’s daily routine, was keeping his mind off the past and focused on the present. He determined to “extract every ounce of diversion and creativeness inherent in my immediate surroundings” by experimenting “with new schemes for increasing the content of the hours.”

In practical terms, this meant challenging himself to do his tasks a little better each day, thereby keeping his focus on positive improvement:

“I tried to cook more rapidly, take weather and auroral observations more expertly, and do routine things systematically. Full mastery of the impinging moment was my goal. I lengthened my walks and did more reading, and kept my thoughts upon an impersonal plane. In other words, I tried resolutely to attend to my business.”

Extracting more content from his hours also meant trying to make the most of the few diversions he had at his disposal. For example, even though he took his daily walks in different directions from his hut, no matter which way he headed the landscape was pretty much exactly the same — a stretch of white, icy homogeneity to the horizon. “Yet,” Byrd notes, “I could, with a little imagination, make every walk seem different.” As he ambled, he would imagine strolling around his hometown of Boston, or retracing the epic journey that Marco Polo took (which he was then reading about in a book), or even exploring what life was like during the Ice Age. “There was no need for the paths ever becoming a rut.”

When it comes to passing through a challenging, largely unvarying season of life, Byrd observed, one must be able to find worlds within worlds; “The ones who survive with a measure of happiness are those who can live profoundly off their intellectual resources, as hibernating animals live off their fat.”

Don’t Worry About What You Can’t Control

“why, I asked myself, weary the mind with small reproaches? Sufficient unto the day was the evil.”

Byrd’s only connection to the outside world was a radio he used to communicate with the men back at Little America. But he found that listening to these dispatches often made him feel more anxious, rather than less.

This was especially true when the men back at base shared an item of national or global news. For example, after “Curiosity tempted [Byrd] to ask Little America how the stock market was going,” he realized the query “was a ghastly mistake.” The glum news (this was during the Great Depression), put him in a state of dejection; before leaving the States, Byrd had invested some funds in the hopes of making some money and defraying the expedition’s costs. Now much of that money had evaporated, and he could only sit idly at the bottom of the world, consumed by the impotent feeling of not being able to do a damn thing about it.

“I can in no earthly way alter the situation,” Byrd eventually concluded. “Worry, therefore, is needless.”

He would thereafter take the same Stoic approach to the dispatches he received from Little America, “clos[ing] off [his] mind to the bothersome details of the world” and concentrating only on that which he could control:

“The few world news items which [were] read to me seemed almost as meaningless as they might to a Martian. My world was insulated against the shocks running through distant economies. Advance Base was geared to different laws. On getting up in the morning, it was enough for me to say to myself: Today is the day to change the barograph sheet, or Today is the day to fill the stove tank.”

One might observe, while Byrd couldn’t do anything about global events from his shack in Antarctica, he couldn’t have done anything had he been back home either. Begging an important question for all: Is there any reason to keep up with the news?

There Is No Peace, No Beauty, No Joy, Without Struggle

There were times during Byrd’s experience that were positively thrilling. Read just a few of the ways he exults in the sublimity of solitude and “the sheer excitement of silence”:

“I realize at this moment more than ever before how much I have been wanting something like this. I must confess feeling a tremendous exhilaration.”

“I came to understand what Thoreau meant when he said, ‘My body is all sentient.’ There were moments when I felt more alive than at any other time in my life. Freed from materialistic distractions, my senses sharpened in new directions, and the random or commonplace affairs of the sky and the earth and the spirit, which ordinarily I would have ignored if I had noticed them at all, became exciting and portentous.”

“This was a grand period; I was conscious only of a mind utterly at peace, a mind adrift upon the smooth, romantic tides of imagination, like a ship responding to the strength and purpose in the enveloping medium. A man’s moments of serenity are few, but a few will sustain him a lifetime. I found my measure of inward peace then; the stately echoes lasted a long time. For the world then was like poetry — that poetry which is ‘emotion remembered in tranquility.’”

“all this was mine: the stars, the constellations, even the earth as it turned on its axis. If great inward peace and exhilaration can exist together, then this, I decided . . . was what should possess the senses.”

“my thoughts seem to come together more smoothly than ever before.”

Yet these moments of elevation did not come without effort, without sacrifice. They were not made possible despite of the difficult, inhospitable conditions of Byrd’s sojourn, but because of them. His reflections upon seeing a stunning display of colors splash across the Antarctic sky, apply just as readily to everything else he experienced on his solo expedition:

“This has been a beautiful day. Although the sky was almost cloudless, an impalpable haze hung in the air, doubtless from falling crystals. In midafternoon it disappeared, and the Barrier to the north flooded with a rare pink light, pastel in its delicacy. The horizon line was a long slash of crimson, brighter than blood; and over this welled a straw-yellow ocean whose shores were the boundless blue of the night. I watched the sky a long time, concluding that such beauty was reserved for distant, dangerous places, and that nature has good reason for exacting her own special sacrifices from those determined to witness them. An intimation of my isolation seeped into my mood; this cold but lively afterglow was my compensation for the loss of the sun whose warmth and light were enriching the world beyond the horizon.”

Byrd could not have seen such sights without traveling to the bottom of the world. He could not have gleaned any soul-expanding insights, without also battling soul-crushing loneliness. There cannot be any sweet without the bitter.

Byrd went looking for, and found, a sense of peace, but, he hastened to explain, the “peace I describe is not passive. It must be won”:

“Real peace comes from struggle that involves such things as effort, discipline, enthusiasm. This is also the way to strength. An inactive peace may lead to sensuality and flabbiness, which are discordant. It is often necessary to fight to lessen discord. This is the paradox.”

The Only Thing That Ultimately Matters Is Family

While Byrd enjoyed two healthy, insight-filled months of solitude, thereafter conditions at Advance Weather Base unfortunately took a near-fatal turn, and cut short Byrd’s sojourn there.

Something went afoul with the stove he used to heat his hut, so that it began to leak carbon monoxide into his tiny living space. If he turned off the stove at night, however, he would freeze. So he was forced to alternate between shutting it off and cracking open the door for fresh air during the day, and letting it run while he slept. Unsurprisingly Byrd became deathly ill and could barely function, a fact he hid from the men at Little America for two months, not wanting them to risk their lives by launching a rescue mission after him.

Though it may be a cliché, as Byrd approached death’s door, he really did see his “whole life pass in review. I realized how wrong my sense of values had been and how I had failed to see that the simple, homely, unpretentious things of life are the most important.”

When Byrd thought of the work he had come to the base to do, the data he had gathered, it all seemed like dross in the grand scheme of things. He realized that the real heart of life was back at home with his wife and kids:

“At the end only two things really matter to a man, regardless of who he is; and they are the affection and understanding of his family. Anything and everything else he creates are insubstantial; they are ships given over to the mercy of the winds and tides of prejudice. But the family is an everlasting anchorage, a quiet harbor where a man’s ships can be left to swing to the moorings of pride and loyalty.”

“The Universe Is a Cosmos, Not a Chaos”

Before Byrd got sick, he gained one of his most profound insights, concerning nothing less than the nature of the universe and man’s place within it.

In gazing upon the stunning expanse of dark sky, and the awe-inspiring dance of Antarctic auroras across it, Byrd found not only beauty, but a pattern to that beauty. In listening into the silence of solitude, he heard the flow of a well-orchestrated cadence:

“Here were the imponderable processes and forces of the cosmos, harmonious and soundless. Harmony, that was it! That was what came out of the silence — a gentle rhythm, the strain of a perfect chord, the music of the spheres, perhaps.

It was enough to catch that rhythm, momentarily to be myself a part of it. In that instant I could feel no doubt of man’s oneness with the universe. The conviction came that that rhythm was too orderly, too harmonious, too perfect to be a product of blind chance — that, therefore, there must be purpose in the whole and that man was part of that whole and not an accidental offshoot. It was a feeling that transcended reason; that went to the heart of man’s despair and found it groundless.”

From this realization came no detailed proclamation on the nature of God, on theology, on the true faith or the right denomination. Byrd simply reached a deep conviction that the universe was not a random chaos, but a planned cosmos; that “For those who seek it, there is inexhaustible evidence of an all-pervading intelligence.”

Conclusion: Commence Your Own Expedition Into Solitude

“Part of me remained forever at Latitude 80 08’ South: what survived of my youth, my vanity, perhaps, and certainly my skepticism. On the other hand, I did take away something that I had not fully possessed before: appreciation of the sheer beauty and miracle of being alive, and a humble set of values. . . . Civilization has not altered my ideas. I live more simply now, and with more peace.”

If you plunged into a prolonged period of solitude and silence, away from every besetting distraction, what would happen to your mind? What insights would you discover? Would they be the same as Byrd’s? Different?

While most of us will never experience a state of silent solitude of the prolonged, all-encompassing kind inhabited by Richard E. Byrd, we can all find more pockets of it in our daily lives. We can all shut off the noise for a few moments, and glimpse more clearly those ideas and revelations that ever edge towards consciousness, only to be pushed away by another distraction.

We can all take our own solitary sojourn; we can all explore the deeper dimensions of silence; we can all discover fresh realizations by journeying to a different latitude of soul.