Alex, one of eight child actors sitting in a circle with John Mulaney, has a grand unified theory about blooper reels that he would like to share right this second. “Before I see a movie, I always watch the blooper reels,” he explains. “If that movie has no fun moments, like, so that means they didn’t even have fun doing it? So then I’m not gonna watch the movie.” Mulaney’s eyebrows fly upward—Alex’s logic is a touch cockeyed but impressive. “That’s brilliant!” he says.

It’s a Tuesday afternoon in July, and he and the actors—ages eight to twelve—are gathered in a fluorescent-lit rehearsal space in Manhattan’s Theater District, here to rehearse his next, as-of-yet-untitled comedy special. A couple years ago, on the same block, he starred with his friend Nick Kroll in a hit Broadway show they cowrote, Oh, Hello, portraying two grumpy, corduroy-sporting septuagenarian weirdos partial to cocaine, casual misogyny, and Steely Dan. Last year, five blocks north, Mulaney did seven straight sold-out stand-up shows at Radio City Music Hall; footage from one of those shows became his third special, Kid Gorgeous. Whereas that one, released by Netflix, was a watchmaker- tight hour of jokes, he’s trying something new this time: a children’s variety show. And these children have a lot to say about bloopers. “I think they should have blooper reels at the end of scary movies so people can go home and not feel terrified,” another kid interjects. “Right,” Mulaney says, nodding. “A catharsis of sorts.” He scans the circle. “This whole special,” he tells the kids, “is going to be a blooper reel.”

Mulaney, thirty-seven, is modeling the new special on the entertainment he loved growing up: 3-2-1 Contact, the eighties-era PBS after-school classic; Really Rosie, a 1980 musical by Maurice Sendak and Carole King; and, of course, Sesame Street. “It’s been on TV how many—fifty years?” Mulaney tells me later. He’s been rewatching old episodes recently, in thrall to their elastic approach to narrative. “It’s modular, fast-paced. Bizarrely paced,” he says. “They’ll cut to a kid who blows up a balloon, draws a smiley face on it, and pops it. Like, ‘Great, love it, moving on!’ ” With the new show,he wants to make something that will appeal to kids and adults alike. His thinking is twofold. “It’s something I’d like to watch,” he says. “And I don’t wanna do anything anyone else is doing.”

Mulaney doesn’t have to do anything he doesn’t want to: A decade into his career, he’s at the height of his powers, with a string of successes to show for it. Kid Gorgeous won an Emmy—his second. His first came halfway into his five-season stint, beginning in 2008, as a writer on Saturday Night Live, during which time he and Bill Hader created the absurdist nightlife correspondent Stefon. Last year, Mulaney signed a multispecial deal with Netflix and, in something like a victory lap, returned to SNL to host. This past March, he hosted again. Among comedians, he’s esteemed across generations: David Letterman has called Mulaney “the future of comedy.” Jerry Seinfeld has said, “He really knows his way around the comedy arts.” Pete Davidson has ranked him in his top five, alongside Eddie Murphy and Dave Chappelle.

This fall, Mulaney and Davidson will head out on a tour—a shared bill that grew out of their offstage friendship. Mulaney invites Davidson to Steely Dan concerts, whereas “Pete invites me over while he gets a tattoo,” Mulaney says. “Like, ‘Yo, I’m getting tatted at my house. You want to come over and we watch Back to School?’ ” One time, Mulaney hung out with Davidson and his then girlfriend Ariana Grande. “We watched a movie together,” he says. “Eighth Grade. Bo Burnham.” He speaks of the tour with the tenderness of an older brother: “I knew Pete loved stand-up more than anything and wanted to get out there.”

But first, the kids’ variety show. In the rehearsal space, it’s time to practice a musical number. A kid named Suri—braided ponytail, colorful printed leggings—launches into a duet with Mulaney. It starts with her repeatedly asking him, over ambling piano accompaniment, to “play Restaurant” with her, where she’s the proprietor and he’s a customer. “Won’t you please play Restauraaaant?” she begs. Mulaney demurs with a singsongy reply. She begs some more till he assents, asking, “Hi, can I come into your restaurant?” The song cuts off and the smile drops from Suri’s face. “I’m sorry,” she says. “We’re closed for a private event.”

Everyone laughs. Mulaney apologizes for his singing, which could be politely described as pitch challenged. Suri is encouraging. “You try,” she tells him. “You try.”

“Suri, it’s not gonna get even a tiny bit better,” he says. “It might get worse.”

The maître d’ has no idea who John Mulaney is. He scrolls through the reservation list, frowning. “John Morane?” he asks. “I might be?” says Mulaney. Rehearsals for the upcoming special have wrapped for the day, and he’s trying to squeeze in a quick bite at a nearby brasserie. As if on cue, a woman approaches. “I’m a huge fan!” she tells Mulaney. The maître d’ looks at her, then at the clean-cut, unassuming guy with the enormous backpack whom she’s praising. “We have a table for you,” he announces.

Mulaney places a spartan order: French- onion soup, tap water, bread. “Food is a nuisance,” he says, eating with astonishing slowness—maybe one slurp per minute—almost to illustrate the point. After this he’s due at a writing session to tinker with the new show’s script. In one sketch, he tells me, “A kid does a book report on A Year of Magical Thinking, by Joan Didion, thinking it was a magic book: ‘Unlike 1001 Marvelous Magic Tricks to Amaze Your Friends, this is a gripping memoir of grief from one of the greatest writers of her generation!’ ” Mulaney pauses. “Someone said to me, ‘You know you mention Joan Didion three times in this special, right?’ ” He shakes his head. “We probably have to cut one of those.”

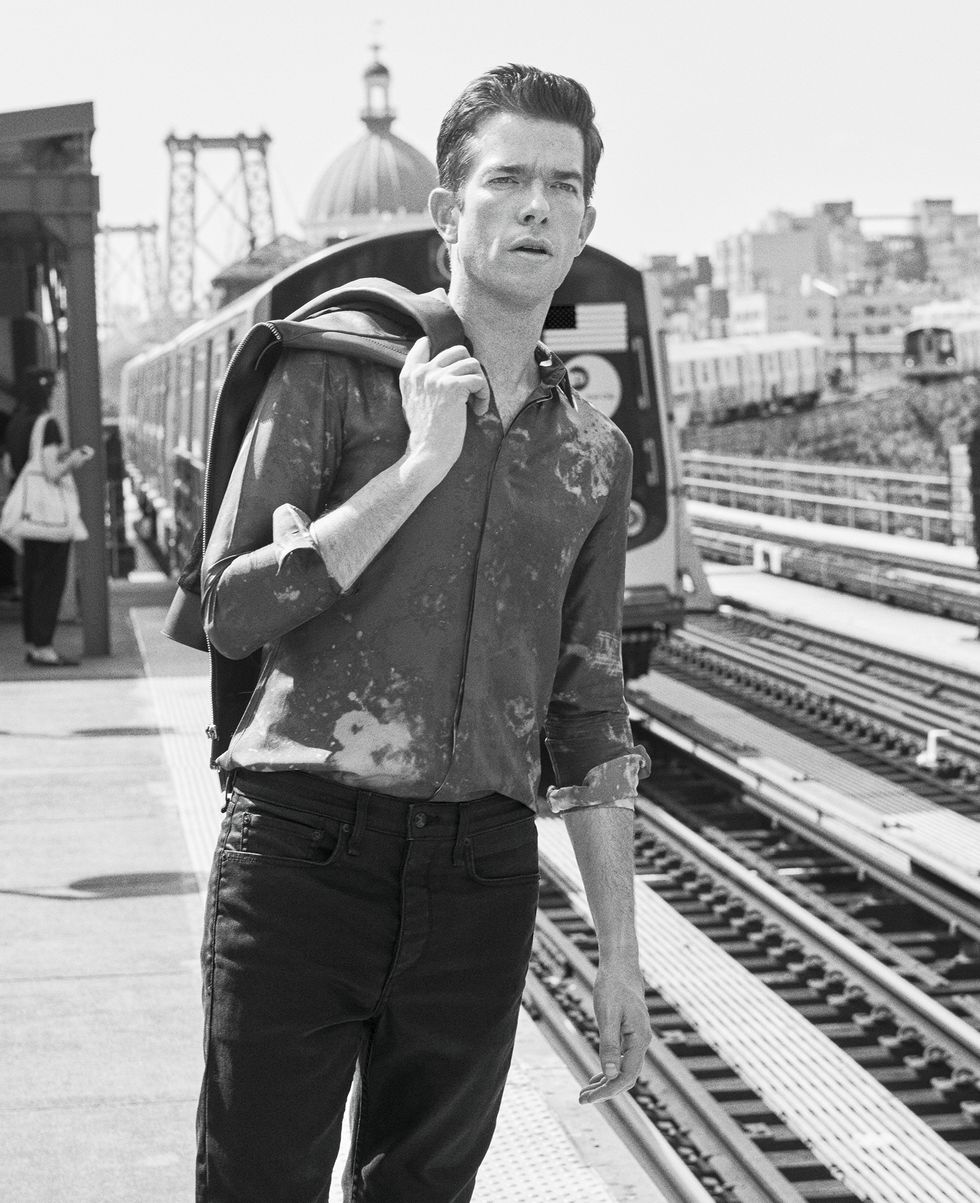

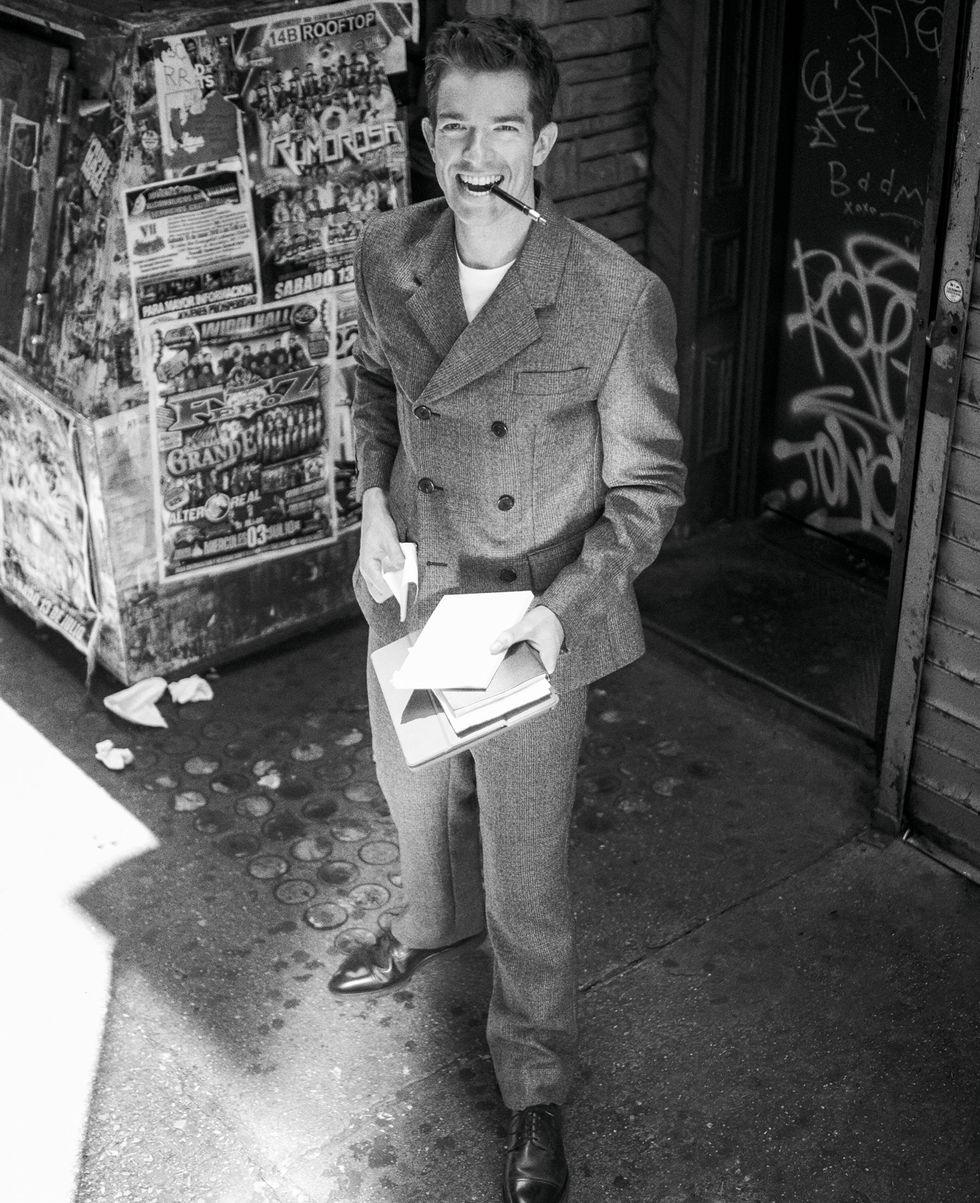

In the world of stand-up, where nothing’s valorized quite like edginess, Mulaney relishes his squareness to an almost defiant degree. The better part of a decade ago, when he was still honing his style in the comedy clubs, Mulaney saw a sea of dudes on stages and in crowds dressed the same way he was, in flannel shirts and jeans. So he began wearing tailored suits onstage and inflecting his delivery with the retro tones and cadences of a fifties TV announcer absolutely crushing an Ovaltine ad. He ignored the trend toward confessional, morally knotty, often filthy humor—pioneered by Richard Pryor, repopularized by Louis C. K.—and dug instead into a finely observed silliness that he aimed at all manner of unlikely subjects: the strictures of his upper-middle-class upbringing, the oedipal weirdness of Back to the Future, the sublime preposterousness of Ice-T’s dialogue on Law & Order: SVU. Mulaney fills his jokes with evocative details and deft turns of phrase. He cares deeply about what you might call joke math, tweaking and deleting to get phrasings just right. “It’s not ‘I was so tired that blah blah blah,’ ” he says. “You want ‘I collapsed.’ ” What’s consistent throughout is his disregard for what’s popular. “I’ve never been relevant,” Mulaney says, “so I’m not worried about feeling irrelevant.”

Like Jerry Seinfeld, one of his biggest influences, Mulaney is obsessed with finding the humor in the quotidian and the banal. He’s never funnier, as far as he’s concerned, than when he gets “exasperated about things you shouldn’t get that upset about.” Trying out new bits, he knows he’s onto something when it feels like “having a crush. When you can’t stop thinking about, like, ‘Why do they do that on House Hunters?’ and your take on it is as strong as something written by Robespierre.” (It takes a unique mind to draw a line between HGTV and the French Revolution.) At one point, out of nowhere, he brings up an obscure poster, depicting a blond woman holding a gyro, that he’s seen hanging for years in restaurants across New York—a sight most of us might clock once, if at all, and then never give a second thought. “I can think about that poster for so much longer than I can think about sex and politics,” Mulaney says.

He is deeply uninterested in political material. At a moment when politics feels impossible to ignore, the furthest into Washington he’s ventured is an extended Kid Gorgeous run in which he likens the president—whom he doesn’t name—to a horse set loose in a hospital. (“It’s never happened before; no one knows what the horse is going to do next, least of all the horse. He’s never been in a hospital before; he’s as confused as you are.”) Mulaney has donated extravagantly to liberal and Left politicians—many thousands of dollars, including at least $1,250 to Bernie Sanders during the 2016 primaries—but keeps such concerns out of his act. “I have a problem with ‘Comedians are really brave and we need them now more than ever,’ ” he tells me. “It’s like, we’re not congressmen. We’re court jesters.”

This article appears in the October 2019 issue of Esquire.

Subscribe

The tricky thing for Mulaney, as a joke purist, is how to come off in his comedy as appealingly out of time without coming off as boorishly out of step or blithely out of touch. His early sets included miscalculations on this score—jokes about the confusing (to him) aesthetics of drag queens and the implicit funniness (to him) of “midgets”; over-the-top impressions of black characters (and one of a mariachi band)—that he’s gotten much better at avoiding. When it comes to the charge among some comedians that so-called PC puritanism is threatening the profession, Mulaney says, “My friend Max Silvestri puts it this way: ‘Why is everyone freaking out about adapting?’ As a comedian, you constantly step on your ego to go, ‘I’d like to be a better comedian.’ ”

The second time Mulaney hosted SNL, this past March, he ended his monologue with a virtuoso imitation of an old-timey police siren. He sustained the sound for a long twelve seconds, then likened it to the dying moan of “an old gay cat.” Given the care that he lavishes on every syllable, I ask whether any word besides gay would have worked there. In part I’m curious on the level of pure joke math. Beyond that, though, Mulaney’s career ascent has coincided with a moment of increased skepticism toward straight white men in comedy, and I wonder how that’s entered into his thinking when he sculpts a joke these days.

“It would be totally dishonest to say it hasn’t,” he says. “I’m a privileged white man who has not had to deal with anything a marginal group deals with. So me saying, ‘No, that word works better’ is, I don’t know. . . .” He tries to make the case for it: “If the world were 1,000 percent different and no one had ever been marginalized? In a vacuum, yes, it was a good word. It’s a detail. A description of something. I tried it on many audiences, and I will trust the audience.” Rather than end there, though, he gets into a back-and-forth with himself about when a detail earns a laugh and when it invokes an easy stereotype. “Let’s think about this for a second,” he says. “I’ve always tried to describe things that I actually saw once. I’m like, ‘This person came up to me and I will tell you what they said to me.’ But I’m open to criticism of that.” He laughs, looking to find his way back out of the weeds. “We’re not a good breed, the white man. We can be trained well, but . . .” He stops to gather his thoughts. His willingness to evolve, he continues, manifests “less in what you see onstage and more in what you don’t.”

In November 2017, The New York Times reported that several female comedians had accused Louis C. K. of inappropriate sexual behavior. At the time, Mulaney and C. K. shared a manager, Dave Becky, who, it was alleged, used his industry power over the years to suppress several of those accusers’ stories. Mulaney quietly fired him, having concluded that Becky was dishonest with him about his role in the scandal. Mulaney doesn’t want to discuss it further on the record. Speaking to Vulture about C. K. and Becky this past March, he said, “Women’s opinions matter, and mine does not.”

In January, Mulaney appeared with Pete Davidson on SNL’s Weekend Update to make fun of Clint Eastwood’s The Mule. Early in the bit, Davidson, who has grappled publicly with mental-health issues, alluded to a note he posted to Instagram last year in which he threatened suicide. On live TV, Mulaney turned to him, and with genuine emotion said, “Pete, look at me, look me in the eye. You are loved by many, and we’re glad you’re okay.”

I ask about this moment a couple days after the rehearsal, over lunch at Russ & Daughters, a gourmet Jewish café that’s like the Willy Wonka factory of kippered herring. (“Please don’t print this if it sounds wrong, but I so identify with the Jewish people,” he says.) “I tell him I love him all the time,” Mulaney says of Davidson. “I have a lot of friends who are like Italian grandmothers, just like, ‘How are you? I love you!’ ” He pauses. “Pete and I came up with that bit together, but in my head, I was like, ‘I hope this is a cathartic thing for him.’ However it came to be, I was very glad it was there.” The Mule routine may have looked like the straitlaced older brother addressing his wayward sibling. But Mulaney’s relationship to self-destructive behavior is more complex: He spent the entirety of his teens and the early part of his twenties as an addict, spiraling out of control. He began drinking at thirteen—initially, he says, to deal with the awkwardness of adolescence, and then to excess, because “alcohol is addictive,” he says, and he didn’t want to stop. “I drank for attention,” he tells me. “I was really outgoing, and then at twelve, I wasn’t. I didn’t know how to act. And then I was drinking, and I was hilarious again.” Drugs soon followed. “I never liked smoking pot. Then I tried cocaine, and I loved it. I wasn’t a good athlete, so maybe it was some young male thing of This is the physical feat I can do. Three Vicodin and a tequila and I’m still standing. Who’s the athlete now?” When Mulaney was a teenager, his parents sent him to a psychiatrist, who told him that he was one part nice kid, one part “gorilla that wants to kill the other half.”

Throughout high school and college, Mulaney kept up his grades while routinely blacking out and doing embarrassing things that friends filled him in on later—going dead-eyed and slapping drinks out of people’s hands, downing a bottle of perfume once. He can pinpoint the day in August 2005 that he finally stopped doing coke, and the day the following month that he gave up alcohol. He was twenty-three. “I went on a bender that weekend that was just, like, fading in and out of a movie,” he says. “It was just crazy. A weekend that was . . . there were . . .” He grimaces. “I’m never going to tell you. That’s mine. I didn’t kill anyone or assault anyone. But yeah, I was like, You’re fucking out of control. And I thought to myself, I don’t like this guy anymore. I’m not rooting for him.” He didn’t use a recovery program—he was able to flip a switch, he says—and he’s been sober ever since.

He spent his childhood in Chicago, raised Catholic by two lawyer parents along with his three siblings, Carolyn, Chip, and Claire. (Claire, his younger sister, also wrote for SNL.) When Mulaney was four, tragedy befell the family: His mother, Ellen, gave birth to a third son, Peter, who, as Mulaney puts it now, “never came home from the hospital.” He says, “I didn’t feel like we were growing up in a house where something had been shattered, if that makes sense. We’d go to his cemetery every year. It was not, like, ‘You don’t mention that.’ But there was a tightness in the air.”

Mulaney was a self-described weird kid with a mile-wide theatrical streak. “We were a good, uptight family, in a fifties way,” he recalls. “There was a lot of fun and love. But a strictness. My parents were a tight unit, like Walter Becker and Donald Fagen,” of Steely Dan. “You couldn’t play one off the other. I said something once, like, ‘Mom sucks!’ And my dad said”—Mulaney’s voice hits a stentorian register—“ ‘That’s my wife.’ And I went to a very strict Jesuit high school, so there was always this, like, ‘Young man, your tie is not straightened.’ ” He found that strictness asphyxiating. Mulaney’s father, a corporate attorney also named Chip, plays a prominent role in his son’s jokes, appearing as a steely enigma under whose weight the young Mulaney squirmed and rebelled. “I remember once I said, ‘Yeah,’ and he turned to me and said, ‘The word is yes,’ ” Mulaney tells me.

He attended Georgetown University, his parents’ alma mater, where he joined an improv group that included fellow comedians Mike Birbiglia, Jacqueline Novak, and Nick Kroll. After graduating, Mulaney went out on tour as an MC and opener for Birbiglia. Later, he landed a Comedy Central job that eventually led to a writing gig on Demetri Martin’s cerebral-absurdist series, Important Things. In 2008, SNL hired Mulaney as a writer, a job he loved—“writing for Fred Armisen is like writing a song for Jimi Hendrix.” He left in 2012 and landed an irresistible deal to write, produce, and star on his own sitcom.

Back then, the dominant style for smart TV comedy was the handheld, laugh-track-free, fifty-jokes-a-minute, single-camera format exemplified by The Office and 30 Rock. Mulaney wanted no part of that. He opted instead for a multicamera sitcom indebted to I Love Lucy and Seinfeld. When Mulaney, as it was called, debuted on Fox in the fall of 2014, the ratings were bad, the reviews abysmal. The network killed it after one truncated season. When I suggest to Mulaney that the show “struggled” for survival, he grins and rejects the euphemism. “We didn’t ‘struggle,’ ” he replies. “We were a clay pigeon shot out of the sky immediately.”

He still has a fondness for Mulaney, he says, while conceding he hasn’t watched it since he was in the editing room. (“I have reread some scripts.”) In a postmortem on the show’s failure, he praises the jokes but faults its normie-sitcom “wrapping paper,” which gave it a generic feel. “I lost the thread; I didn’t aim it right,” he says in between nibbles of an everything bagel. “It didn’t welcome in the people that knew who I was, and everyone else didn’t know who I was.” Instead of wallowing, he flung himself back out onto the road mere days after the cancellation—reorienting himself, city after city, by concentrating on the thing he did best: getting a room of strangers to laugh. The resulting special was called The Comeback Kid.

“I’m an entertainer, not an artist,” he says. “I do it for audiences. I do it for people to consume. There’s a Rilke thing about how a true poet would write every day in a jail cell, poems no one would ever see. I’m not in tune with that. I want people to have a good time.” As a comedian, you become profoundly dependent on the laughter of strangers, not only for your livelihood but for your sense of identity. On the surface, telling jokes for a crowd resembles a good-natured powwow for like-minded people, yet there’s something irreducibly antagonistic about it, too, with the balance of power whipping back and forth between the guy onstage and the people sitting in judgment of him. “The audience is both looking up to you,” Mulaney says, “and they are Mount Olympus.”

His foray into network sitcoms did teach him an important lesson. “There’s a benefit to failure,” he’s said. “It gives you an existential ‘Who cares?’ ” Or as he expresses it now, “Sometimes you need to say, ‘Fuck the audience.’ ”

“Are you still working on that?” our waitress asks. There’s a fat mound of golden-pink lox in front of Mulaney; he sends it to the compost bin along with the bagel and asks for the check.

He’s got a meeting in TriBeCa, so I walk him there. When we arrive, we notice an intercom next to the door, but instead of buttons beside names there’s a keypad for dialing tenants. Though Mulaney’s on time, he doesn’t know the number he’s supposed to punch in. That means he’s going to be late, which he doesn’t like at all. He emits a sound of pure anxiousness: “Uhhh. . .” Maybe the number is in his email? He takes out his phone, digs around. I leave him there as he shouts a distracted goodbye in my direction and swipes at his screen—exasperated about something he shouldn’t get that upset about.