Forty days, or “quaranta giorni”: That’s how long the city of Venice, Italy kept foreigners and boats in a lagoon to stem the spread of Black Death in the 14th century. It’s the genesis of the word “quarantine,” which has since come to mean any isolation for an amount of time of a group of people who may have been exposed to a communicable disease.

Unfortunately, the word is back in vogue in 2020.

Last month, authorities quarantined passengers on the Diamond Princess cruise ship in Japan for two weeks in an attempt to arrest the spread of coronavirus, which can lead to respiratory illness. This strain, known as COVID-19, has been linked to more than 95,000 cases and 3,200 deaths worldwide, including 11 deaths in the U.S. as of press time. Following the quarantine, officials confirmed 542 cases among the passengers, more than anywhere else outside of China.

“Obviously the quarantine hasn’t worked, and this ship has now become a source of infection,”Dr. Nathalie MacDermott, an outbreak expert at King’s College London, told the Associated Press.

The sickness might have spread among Diamond Princess passengers because a cruise ship isn’t the best quarantine setting. Many ships use recirculated air, and thus have the high potential to be a breeding ground for illness. But the quarantine might have also failed for a simpler reason: The concept has outlived its efficacy.

At one point in human history, quarantines served a valuable role in stopping the spread of communicable diseases. But with the advent of modern medicine, they’re no longer a solution for any health benefit—just a way to allay panic in the general population.

Keep the Sickness Contained

The concept of separating healthy and sick people dates back to ancient times. The Old Testament book of Leviticus decreed that lepers needed to live away from people in separate camps, yelling “Unclean! Unclean!” to announce their presence. This led to the idea of leper colonies; as late as the 1960s, a peninsula on the Hawaiian island of Molokai still housed one such colony.

(According to Leviticus, after their periods, women were also expected to undergo certain cleansing rituals as well. Even today, some eastern cultures have separate shacks for women to live in while menstruating.)

In the 14th century, the Black Death raged across the world, and it’s estimated that bubonic plague killed anywhere from a quarter to a half of the population in Europe, the Middle East, China, and North Africa.

The Adriatic port city of Dubrovnik, in what is now Croatia, was an important way station between east and west. On July 27, 1377, the Great Council of Dubrovnik decreed that any traveler to the walled city (which remains a tourist destination today as a filming location in Star Wars and Game of Thrones) would have to spend 30 days in a spot outside the city to see if plague symptoms developed.

The city of Venice built a building called a Lazaretto in 1423 to serve as a quarantine facility, and that term was used again in 1799 for a similar building in Philadelphia, not far from where the city’s airport is today. That Lazaretto, constructed following a yellow fever epidemic that killed 10 percent of the city’s population, was a main entryway into the U.S. for an estimated 225,000 slaves and immigrants. In fact, it’s estimated that one of every three Americans can trace their ancestry back to someone who passed through the stately building.

At that point, and well into the 19th century, the root causes of disease were ascribed to a variety of reasons, more supernatural than natural. (Think: bad spirits, karmic retribution for sins, and imbalance of the natural humors.) But in the late 1800s, a German scientist named Robert Koch developed a theory that illness was caused by some type of microorganism that could be isolated and studied. Koch studied tuberculosis, a highly communicable bacterial infection that led to respiratory problems and coughing up blood, and ultimately won the 1905 Nobel Prize in Medicine for his work.

(A quick aside: Because superstitions are difficult to shake, some people believed that tuberculosis victims were actually vampires, and returned from beyond the grave to drain their loved ones’ life forces. In actuality, those who cared for tuberculosis patients were themselves succumbing to the disease. But in New England in the 1800s, believers exhumed and beheaded the victims’ bodies and set their hearts ablaze; after all, that’s how you killed vampires. News of the “vampire panic” spread far and wide, including to England, where novelist Bram Stoker is said to have incorporated elements of the hysteria into Dracula.)

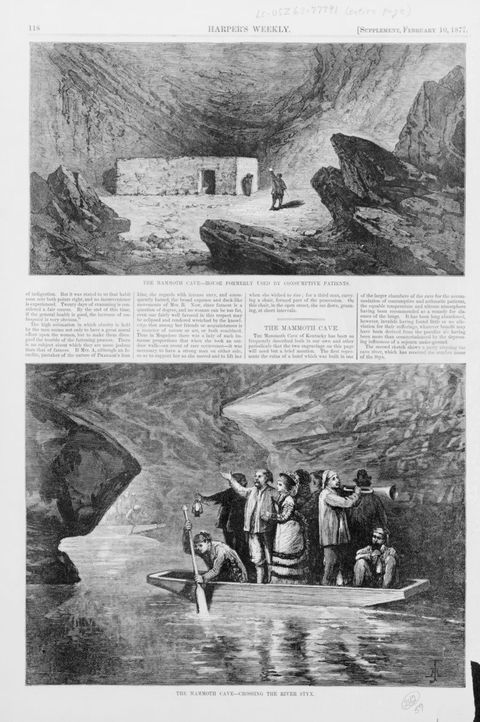

Even before Koch’s work with germ theory, doctors used isolation to treat tuberculosis. Dr. John Croghan bought a network of caves in his native Kentucky in the hopes that the damp air would ameliorate symptoms. It didn’t work—Croghan himself died of the disease—but the Mammoth Cave remains a popular tourist destination as the longest cave network in the world and part of the National Parks System.

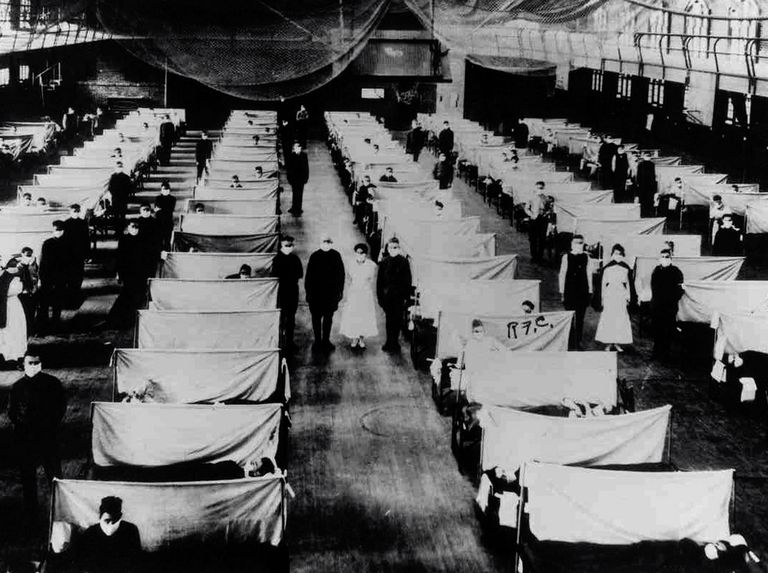

Croghan’s idea of separating tuberculosis patients from the general population had merit, and the late 1800s and early 1900s saw the construction of a network of sanatoriums, many of which became vibrant, self-sufficient farming communities. Doctors administered the first tuberculosis vaccine—based in part on Koch’s research—in 1921, and slowly, the need for sanatoriums disappeared. Other “miracle drugs” like penicillin and sulfa soon followed, sped along by use for treating wounded and ill World War II soldiers.

Scientists introduced the first polio vaccine in 1952, and the following decade brought successful vaccinations for measles and mumps. It appeared that the era of quarantine as a medical treatment had come to an end. But one small, albeit world-famous group of people still required isolation: the astronauts going to the moon.

Germs from Beyond

Nobody was sure what the crew of Apollo 11 would encounter on the moon. (For all we knew, it really could have been green cheese.) To ensure they didn’t incubate any earthbound diseases, then, the astronauts’ quarantine began even before their July 1969 launch—and that posed a political problem.

Richard Nixon, sworn in as president that January, wanted to have dinner with the astronauts, and it fell to Dr. Charles Berry to explain why he couldn’t. Berry later said in an interview for NASA’s oral history project that it was “as close as I ever came to getting fired in my life.”

Even at the time, NASA realized it was likely an unnecessary procedure—and astronaut Michael Collins said it might not have done any good. “The command module lands in the Pacific Ocean and what do they do? They open the hatch,” he recalled in an interview. “You gotta open the hatch. All the damn germs come out!”

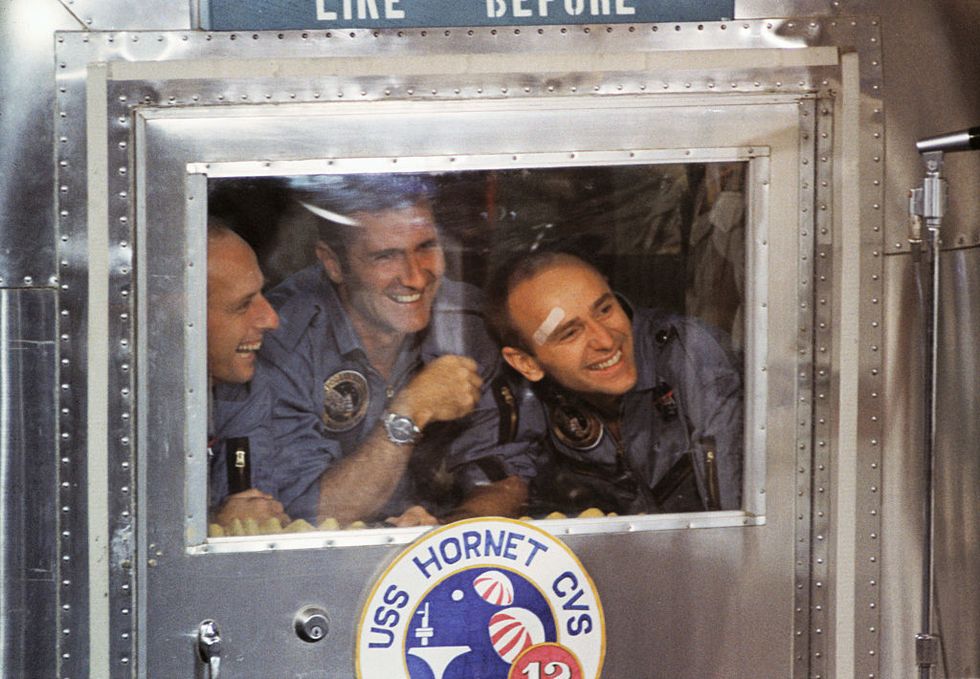

A swimmer opened the hatch and gave Collins, Neil Armstrong, and Buzz Aldrin isolation suits for them to wear as they were taken to a mobile quarantine facility (MQF) on board the U.S.S. Hornet. They would spend 21 days in isolation. In fact, Armstrong celebrated his 39th birthday while quarantined.

The MQF was a 35-foot Airstream trailer modified to include living and sleeping space and provide a sterile environment for the astronauts to be watched. The aircraft carrier then sailed to Pearl Harbor, and later flew to Johnson Space Center in Texas. That MQF is on display at the National Air and Space Museum Udvar-Hazy Center in Virginia. NASA repeated the process for the Apollo 12 and 14 missions, but ultimately deemed it unnecessary for the three subsequent missions to the moon.

Modern Panics and Pandemics

In the early 1980s, reports started emerging of a mysterious “gay cancer” being seen in New York and San Francisco. Doctors suddenly started seeing Kaposi’s sarcoma, a rare and slow-acting cancer, in young gay men, who either died quickly of the disease or pneumonia and other illnesses characterized by immune system failure. The disease was initially called GRID, for Gay-Related ImmunoDeficiency, but once scientists realized it wasn’t limited to the gay community, they gave it the name it’s known by today: AIDS.

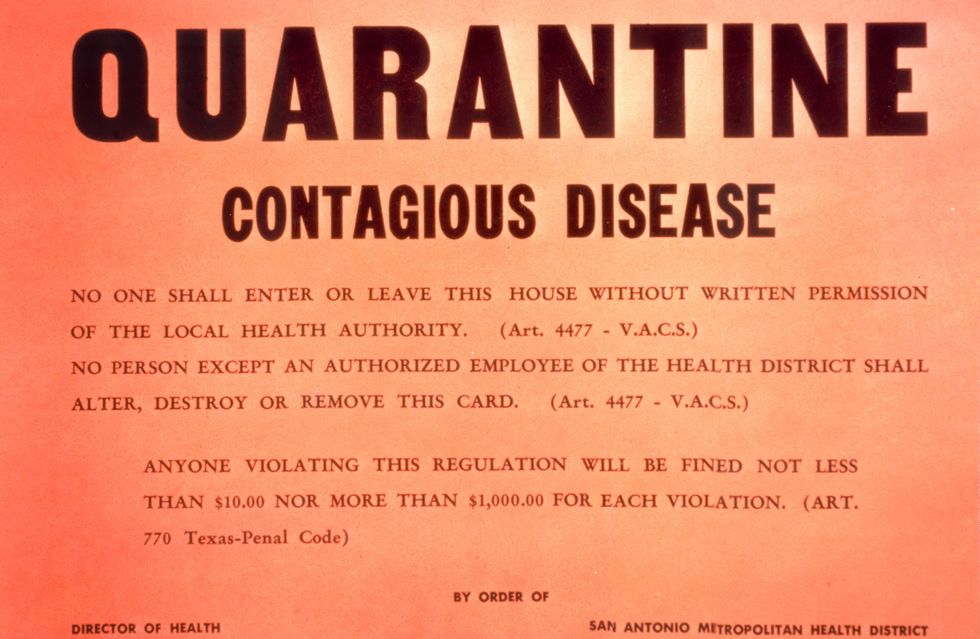

Ignorance and fear ran rampant. The New York Times said people viewed the disease as “a sort of immunological time bomb.” Treatment was expensive—on average, $64,000 per patient in the 1980s—and the disease still seemed irreversible. William F. Buckley said AIDS patients should be tattooed. Children diagnosed with the disease weren’t allowed to attend school. Some states raised the specter of quarantine in the name of public safety, proposing it for drug addicts and sex workers. But as people learned more about the spread of AIDS—either through blood or sexual contact—the idea of quarantine was proven ineffective.

The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 brought with them sweeping changes in the state security apparatus, from the creation of the cabinet-level Department of Homeland Security and the Transportation Safety Administration to the passage of the PATRIOT Act, expanding surveillance and investigation capabilities.

But you might not know 9/11 also spurred the Model State Emergency Health Powers Act, model legislation drafted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as fears mounted of the use of biological weapons. (Shortly after 9/11, government officials and journalists received envelopes with anthrax powder. In all, four people died in what the FBI called Amerithrax.) The act allowed for sweeping quarantine powers by governing bodies, and organizations across the political spectrum reviled it; both the Heritage Foundation and the American Civil Liberties Union offered full-throated opposition. Elements of the model legislation found their way into state laws, but nothing that would have granted that type of power.

Concerned parties also mounted calls for quarantines for SARS—a virus related to coronavirus—during its outbreak in 2003, and during the Ebola virus’s spread in Africa in 2014. While quarantines were effective in some instances against SARS, they mostly struck others as political grandstanding related to Ebola.

“History is repeating itself, as the irrational, punitive measures deployed in the AIDS epidemic 30 years ago are revived for another disease, this time a rare hemorrhagic fever responsible for only a few local cases,” AIDS activists Gregg Gonsalves and Peter Staley wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine at the time.

Now, as the world reckons with another pandemic in Coronavirus, are we on the verge of making the same quarantine mistake again?

Vince Guerrieri is a writer based in the Cleveland area. He's the author of two books, and his byline has appeared in Deadspin, Jalopnik, CityLab and POLITICO, among other places.