Your screenplay is a highly-specific document which forms a template for talent to convert it into a film or TV show. Creative Screenwriting spoke to Jacob Krueger about how screenplay format has evolved and how screenwriters can manipulate (or bypass) traditional screenplay formatting rules, to create a satisfying document for a script reader. He discusses this in light of the highly successful horror film ‘A Quiet Place.’

Everyone who knows anything about A Quiet Place has commented on the way the film uses the visual medium directorially to tell a story with hardly any dialogue at all.

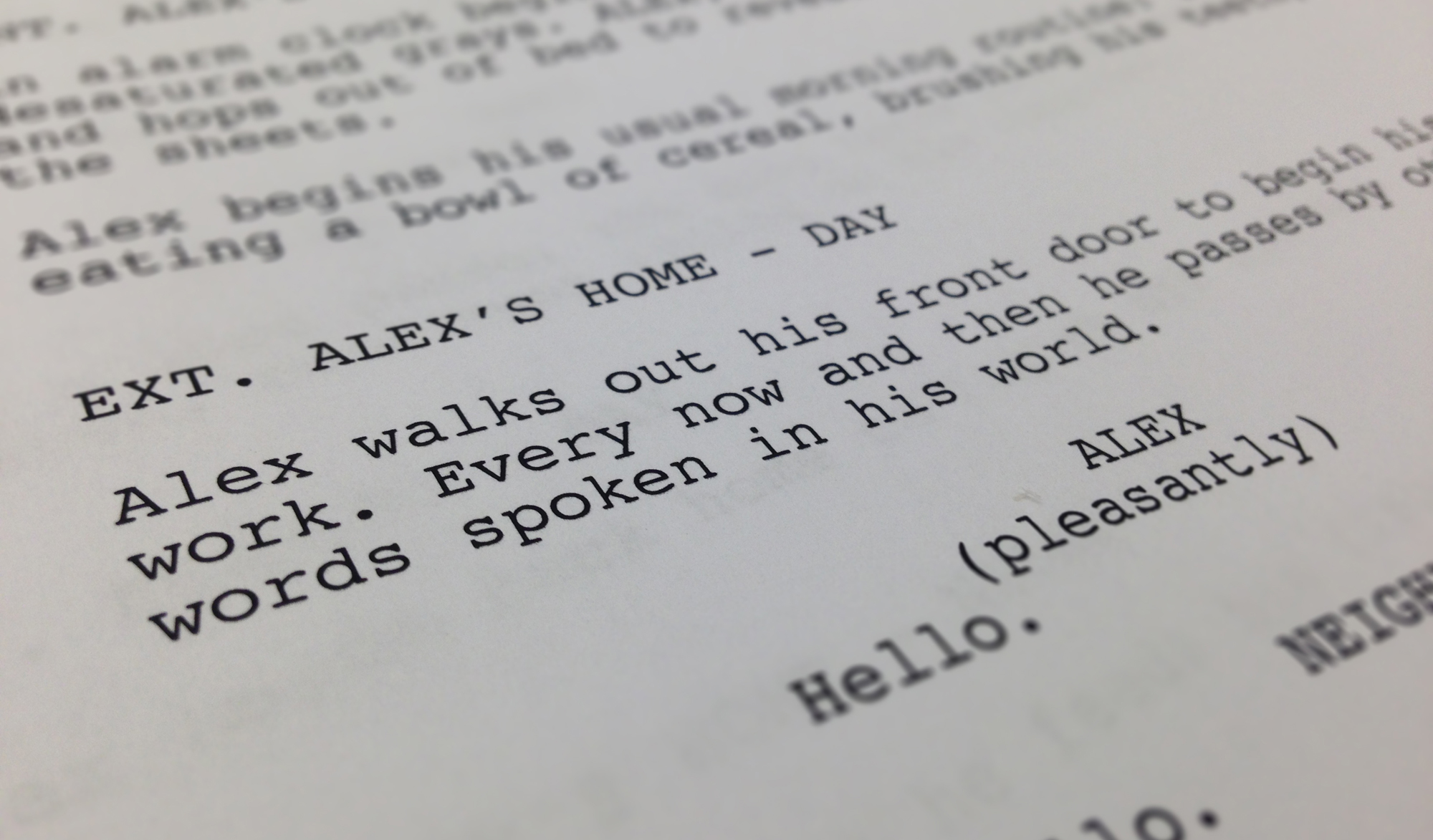

But what very few people are talking about is how this relates to how a screenwriter gets action like that on the page, and one of the most important concepts in screenwriting: formatting.

Many screenwriters feel like the formatting is a counterintuitive process, a grammatical set of rules by which they somehow have to abide. And if you think about formatting in this way, it isn’t going to free up your creativity, and it isn’t going to be a lot of fun.

The truth is, screenplay formatting exists for only one purpose: to Isolate the Visual Moments of Action in your script.

Using formatting in this way will allow you to hypnotize your script reader, so they can forget that they are reading a screenplay, and instead slip effortlessly into the visual world that you are creating for them. If hypnotizing your reader sounds a little scary, I would like to remind you that you are actually hypnotizing yourself all the time. Every time you write you are entering a hypnotic state. And if you’ve ever seen a movie, you’ve also entered a hypnotic state.

In fact, it is impossible to enjoy a movie without entering a hypnotic state because we have this problem called “suspension of disbelief.”

Everybody thinks the suspension of disbelief is something that the audience chooses to do, but it is actually quite the opposite.

Suspension of disbelief is something that happens to you in a hypnotic state–when a movie becomes more like a dream, when you forget that you are sitting in a theater or reading a script and start to actually see the world through the eyes of the characters.

When you start to experience a movie in this state, suddenly time slips away, and suddenly you are crying over things that you know aren’t real. Your heart is racing for characters facing monsters that don’t exist, and you are having an emotional reaction to things that you know are made up.

And truly great script formatting allows you to conjure up this experience for your audience, right there on the page.

If you read the original screenplay for A Quiet Place, you will see something very unexpected in the formatting. A single line, oddly centered, right at the end of page 15, “THIS IS THE LONGEST WALK OF HIS LIFE.”

And when you flip to page 16, you’re going to see something even stranger: one line surrounded by white space: “John is 30 feet away from the shed…”

Then another single line on page 17 surrounded by white space: “20 feet away.”

Page 18: “10 feet…”

Page 19: “5…”

Page 20: “…SNAP.”

And then suddenly we are back on page 21 in screenplay format again.

Now, if you read The Hollywood Standard, which is essentially the Strunk and White’s Grammar of Screenwriting, the formatting book that tells you the rules of what screenplay formatting is and how it is supposed to work, that book would tell you that the formatting I just described to you is 100% wrong.

But, having read the description of those pages, you probably found yourself feeling something. You probably found yourself experiencing the length of that walk, the feeling of that walk, and the isolated moment of that snap, how loud that snap needs to feel, how long that piecing needs to feel.

This is the purpose of formatting: to Isolate Visual Moments of Action to create the emotional response in your reader that makes it impossible for them to disbelieve.

If you saw A Quiet Place you know what I’m talking about.

Even though there is an intellectual part of your mind that knows that this doesn’t totally make sense, that’s wondering “What happens if you cough in this world?” “Why don’t they just go live under the waterfall where they can talk freely?”

But even though you know intellectually it doesn’t all make sense, because of those isolated visual moments of action there is a subconscious part of your mind that doesn’t know, that is pulled into the story whether you like it or not, that feels your heart beating at every moment.

You simply can’t help but experience this terror in the same way that these characters are experiencing it.

This is the power of isolated visual moments of action. They are how we process our world.

A Quiet Place is a very special movie. So, unless you’ve got a really good reason, please don’t go out and put a single line on a whole page of your own film script.

But do take this idea as a way of thinking about formatting.

Formatting doesn’t exist to follow the rules. Formatting exists to create a feeling for the audience, to allow your audience to see, hear, and feel your movie in the little movie screen in their minds.

No two screenwriters format the same way, and even two screenplays from the same writer are likely formatted quite differently, because the formatting that you are using is designed to communicate the feeling of the script, and certain scripts need to feel different from others.

If you are writing a film script like A Quiet Place, which happens in a world with hardly any sound, your script is mostly going to be action. And if you are writing a script like an Aaron Sorkin movie, your writing is mostly going to be dialogue.

If you are writing an action sequence, your formatting should feel high paced and visual. If you are writing a romantic love story, your writing should have that feeling of romantic magic. Your formatting should exist to create the feeling of tone, of speed, of action, of the script.

In fact, your formatting should work to allow the movie to play in the mind’s eye of the reader at the same pace that you experience it, at the same pace that the audience will experience it on the screen.

So, what does it mean to Isolate Visual Moments of Action in your script?

Isolate means that, in a movie, no two things are happening at the same time. So you, as a writer, need to think of each line you write, whether it’s action or dialogue, as an isolated moment, which, when bumped up against another isolated moment, invites the audience to tell themselves the story of your movie.

Visual means there is something visually compelling about each isolated moment– something specific and unique that differentiates it from other images of its kind that we’ve seen in other films and allows your audience to instantly picture it in their mind’s eye in the same way a great director would capture it on the screen.

Moment means that we want to capture the moments that matter– the greatest hits moments, and not all the boring stuff in between. It means seeking and destroying anything normal in your script, and distilling your action down, like a poem, until every line counts.

Action means that we want to focus on the verbs– the things our characters are doing, and the choices they are making. Your director is always going to cut on action, so you want to cut on action as well, to capture all those little specific choices your characters make.

It’s likely that if you’re reading this article, you’re familiar with my Write Your Screenplay podcast (and if you aren’t, check it out on Itunes, and you can get even deeper into these concepts!)

If you were writing a screenplay about my life, and you wanted to capture me recording the podcast, you might think the action could be something like “Jake is recording his podcast while sitting at his desk.”

That sounds like action but it is actually not. It’s not action because it is not Isolated. Two things are happening at the same time. It’s not Visual because there’s nothing visually specific or compelling about the way it’s put on the page. It’s not a Moment because there are no choices happening that could reveal who or how Jake is as a character. And it’s not Action because there are no active verbs. Jake is in a state of “recording” and “sitting”, like a character posed for a portrait. But he’s not actually doing anything.

And all this means that even though it looks like proper action and proper formatting, writing action this way means you’re not actually thinking like a screenwriter.

The director can’t shoot it that way (at least not if she’s good) and the reader can’t see it that way (unless they’re super creative). Rather than seeing a series cool images that invite them to tell themselves the story of who Jake is, they’re just going to see a guy sitting at his desk

But if you Isolate those Visual Moments of Action— “Jake’s hands tip the microphone towards his mouth. His lips move within a bushy grey beard.”

Well, now suddenly you are starting to get an image of Jake. You just saw these two moments, one isolated image of the hands tipping the microphone, the second isolated image the mouth moving in the beard, and you told yourself the story.

Notice I didn’t have to tell you it is an INSERT or a CLOSE SHOT. You automatically saw the CLOSE SHOT in those two isolated images.

And even though I haven’t even told you that Jake is recording that podcast, you put together the hand on the microphone and the moving mouth, and you told yourself the story of Jake is recording something. In the gap between those two isolated images, you were invited to tell yourself the story.

And this is one of the coolest parts of formatting because it’s the place where the technical craft of screenwriting and the art of screenwriting actually converge.

Because once you start to think about each image as an isolated moment, you can get really efficient as a writer. Thinking about one image, and then asking yourself “what’s the coolest thing to cut to from there?”

Rather than tracking your character entering, exiting, or walking across the room like you would in a play, you can start to collect the greatest hits isolated visual moments of action that tell the story to your audience.

For an example of how this worked in A Quiet Place, just think of that very first scene.

(Here’s a deeply abbreviated version reconstructed from memory from what I saw on the screen)

Bare feet walk silently on a trash strewn floor.

Racks of tossed about products.

Those two images and we’re already telling ourselves “post-apocalyptic” — something is wrong.

A child walks silently down another aisle.

There’s more than one person. How do they relate? What are they looking for?

Another child.

Is this a family? Are they hunting each other? Are they afraid of each other?

A woman’s hand reaches through bottles of prescription medicine. Carefully extracts one.

Oh, that’s what they’re looking for.

A rocket ship toy on a top shelf.

The little boy reaches up to get it.

I don’t think that’s what he’s supposed to be doing…

It falls.

His mother dives to catch it– just in time!

These people are terrified of noise. The boy wants that ship. But what would have happened if it crashed to the floor?

One line of whispered dialogue: “Too loud.”

Probably it’s not even necessary. Because we’ve already got it.

The woman takes the rocket away from the boy.

Takes out the batteries.

Sets it down on the counter.

No– don’t turn your back on that kid!

The daughter hands the little boy’s the rocket ship. Puts her fingers to her lips, shh…

No, no, no!

The little boy pockets the batteries as well.

NOOOOOO!

And that’s all it takes to set up one of the most disturbing scenes ever in a horror movie.

I’m not going to ruin the upcoming “Bridge Scene” for you, but if you have seen A Quiet Place, you already know about it.

And even if you haven’t seen it, you are already anticipating it…

You see, all those Isolated Moments of Visual Action added up and let you tell a story to yourself. And it’s a pretty darn scary one. You may not have a clue what everyone is so afraid of, but you know it’s going to be bad.

You’re not having the story explained to you. You’re seeing the story in your mind’s eye. You’re making the connections–isolated visual moment of action to isolated visual moment of action.

If you want to try this in your own screenwriting, take a moment to look very closely at a scene you’ve written. Ask yourself, what do I see first, what do I see next, and what do I see after that. What’s visually specific about that image?

Play it in the little movie screen in your mind.

If you’re moving too slowly, ask yourself, “what’s the coolest thing I could cut to?” “What are the greatest hits?” What are two isolated moments that could rub together to create pressure– to invite me to tell myself the story of the movie?

Jacob Krueger is a WGA Award Winning Screenwriter, founder of Jacob Krueger Studio and host of the Write Your Screenplay Podcast.