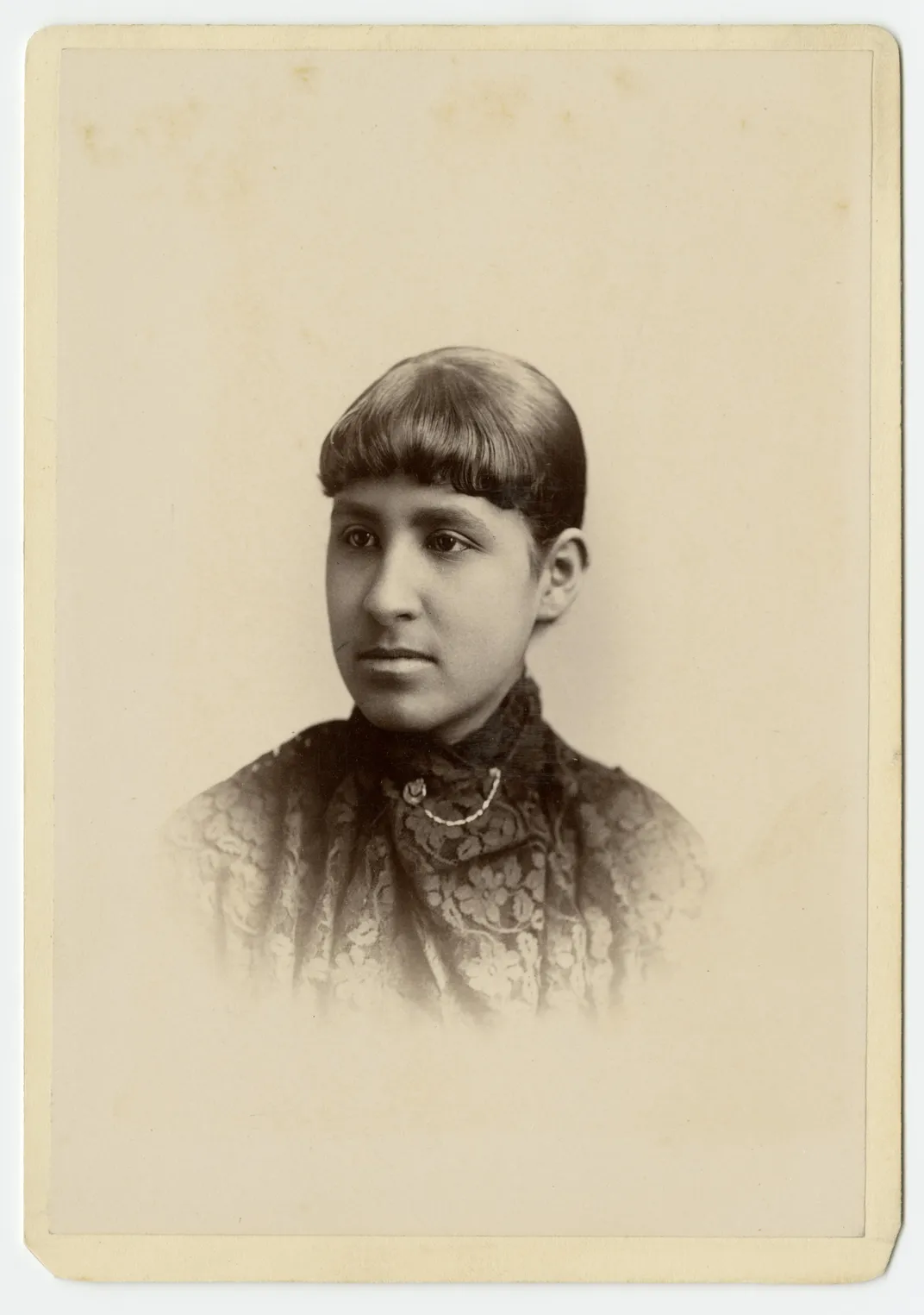

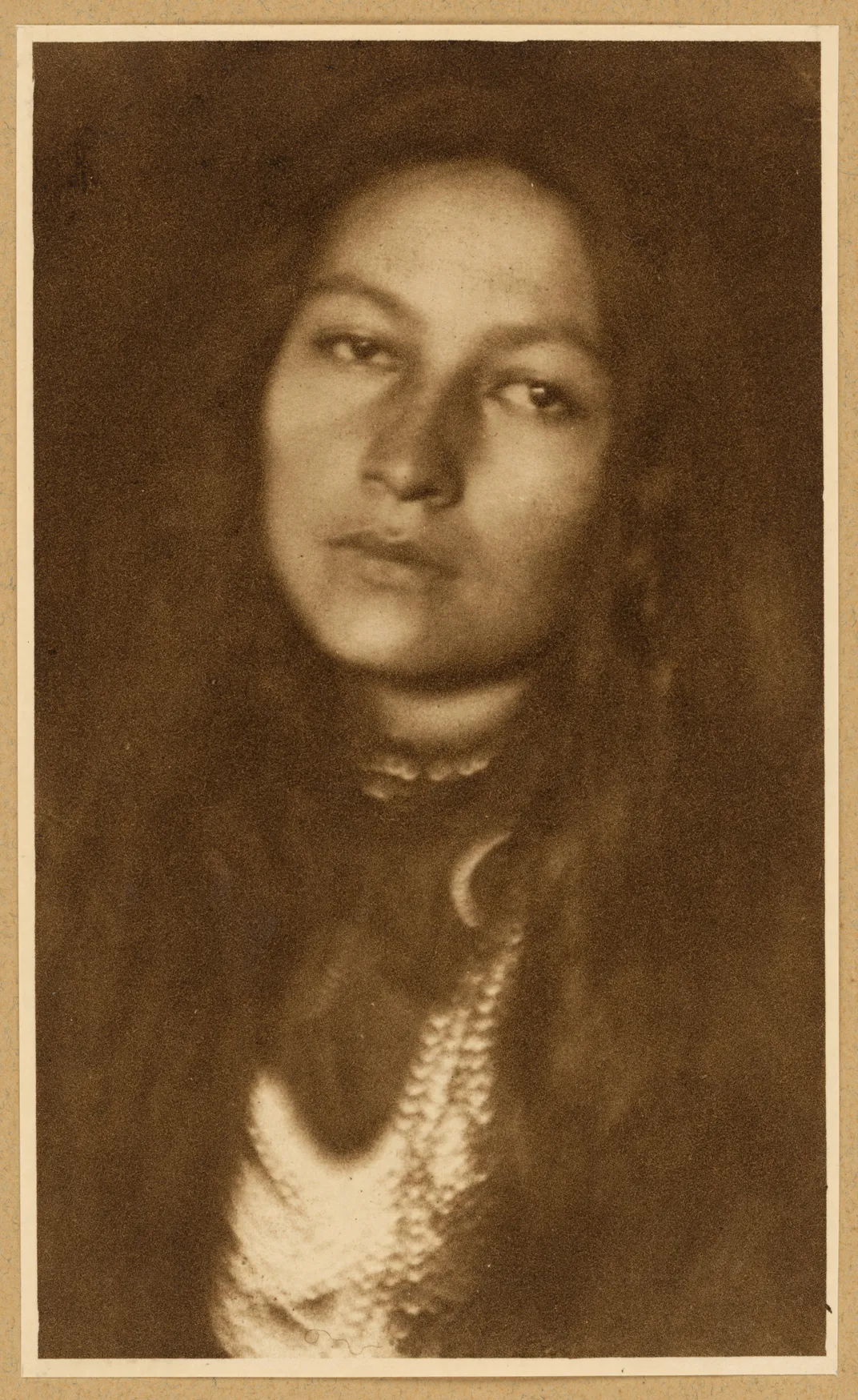

If you look at black-and-white photographs of suffragists, it’s tempting to see the women as quaint: spectacles and undyed hair buns, heavy coats and long dresses, ankle boots and feathered hats. In fact, they were fierce—braving ridicule, arrest, imprisonment and treatment that came close to torture. Persistence was required not only in the years before the 19th Amendment was ratified, in 1920, but also in the decades that followed. “It’s not as though women fought for and won the battle, and went out and had the show of voting participation that we see today,” says Debbie Walsh, director of the nonpartisan Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University. “It was a slow, steady process. That kind of civic engagement is learned.”

This forgotten endurance will be overlooked no more, thanks to “Votes for Women: A Portrait of Persistence,” a major new exhibit at the National Portrait Gallery through January 5, 2020, that features more than 120 artifacts, including the images and objects on these pages. “I wanted to make sure we honored the biographies of these women,” says Kate Lemay, a Portrait Gallery historian and the curator of the exhibit, which portrays the suffragists as activists, but also as students, wives and mothers. “I wanted to recognize the richness of their lives,” Lemay says. “I think that will resonate with women and men today.” The exhibit is part of the Smithsonian American Women’s History Initiative, intended to be the nation’s most comprehensive effort to compile and share the story of women in this country.

The suffrage movement began in the 1840s, when married women still had no right to property or ownership of their wages; women were shut out of most professions, and the domestic sphere was considered their rightful place. The idea of women casting ballots was so alien that even those who attended the landmark 1848 Seneca Falls Convention on women’s rights found it hard to get their heads around it. The delegates unanimously passed resolutions favoring a woman’s right to her own wages, to divorce an abusive husband and to be represented in government. A resolution on suffrage passed, but with dissenters.

Twenty years later, just as the movement was gaining traction, the end of the Civil War created a new obstacle: racial division. Though many white suffragists had gotten their start in the abolition movement, now they were told that it was what the white abolitionist Wendell Phillips called the “Negro’s hour”: Women should stand aside and let black men proceed first to the polls. (Everyone treated black women as invisible, and white suffragists marginalized these allies to a shameful extent.) The 15th Amendment gave African-American men the right to vote; differences among suffragists hobbled the movement for 40 years.

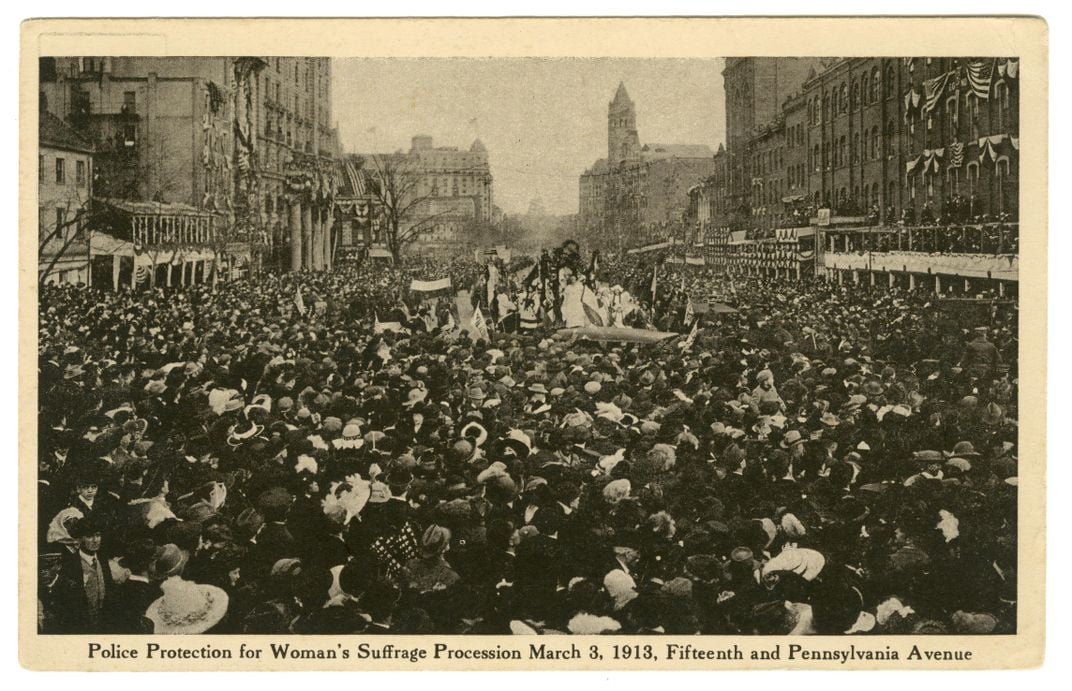

Even after a new generation took up the cause, one faction favored incrementalism—winning the vote one state at a time—while another wanted a big national victory. In 1913, young radicals, led by Swarthmore graduate Alice Paul, kicked off a drive for a constitutional amendment with a parade down Washington’s Pennsylvania Avenue featuring more than 5,000 marchers as well as bands, floats and mounted brigades. Tens of thousands of spectators packed the streets, many of them men in town for Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration the next day.

“No one had ever claimed the street for a protest march like this one,” Rebecca Boggs Roberts writes in her book Suffragists in Washington, D.C.: The 1913 Parade and the Fight for the Vote. Spectators started hurling slurs and more at the marchers—scores ended up in the hospital—but the headline-making fracas played into the women’s desire for publicity.

Radical suffragists began picketing the White House by the hundreds, even in the freezing rain that attended Wilson’s second inauguration four years later—“a sight to impress even the jaded senses of one who has seen much,” wrote Scripps correspondent Gilson Gardner. As the pickets continued, women were arrested on charges like “obstructing sidewalk traffic.” Nearly 100 of them were taken to a workhouse in Occoquan, Virginia, or to the District of Columbia jail. When some of them went on a hunger strike, they were force-fed via a tube jammed into the nose. “Miss Paul vomits much. I do too,” wrote one, Rose Winslow. “We think of the coming feeding all day. It is horrible.”

But on January 10, 1918, Jeannette Rankin, a Republican House member from Montana—the first woman elected to Congress—opened debate on the Susan B. Anthony Amendment, which would prohibit states from discriminating against women when it came to voting. On August 18, 1920, Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify it, and the 19th Amendment was promulgated on August 26.

Many histories of the suffragist movement end there—but so much more was still to come. Some states disenfranchised women—particularly black and immigrant women—by instituting poll taxes, literacy tests and onerous registration requirements. And many women didn’t yet see themselves as having a role, or a say, in the public sphere. People “don’t immediately change their sense of self,” says Christina Wolbrecht, a political scientist at the University of Notre Dame. “Women who came of political age before the 19th Amendment was ratified remained less likely to vote throughout their entire lives.” The debate over the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which at first addressed only racial discrimination, included a key moment when Representative Howard Smith, a powerful Virginia Democrat, inserted “sex” into the bill in a way that led many to believe he was trying to tank it. The gesture backfired—and the bill passed. “Women get equality on paper because of a political stunt,” says Jennifer Lawless, Commonwealth professor of politics at the University of Virginia. In 1964, women outvoted men numerically—37.5 million men versus 39.2 million women—and the trend continued.

By the 1970s, as a result of feminism and the movement of more women into the workplace, women finally understood themselves to be autonomous political actors. And in 1980, the fabled gender gap emerged: For the first time, women voted in greater numbers and proportions than men, and began to form blocs that candidates ignored at their peril.

Women’s representation in office remained tiny, though; to date, just 56 women have served in the Senate and 358 in Congress overall. But as of this writing, a record 131 women are serving in Congress, a woman wields the House speaker’s gavel, and five women have announced plans to run for president in 2020. True, the officeholders’ numbers skew strongly Democratic, and full parity for women will depend on the election of more female Republicans. And yet, something has changed, something real, says Walsh: “We’re in a new era of women’s engagement.”

:focal(2619x1579:2620x1580)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/85/cc/85ccfaa2-44f2-4213-bd1e-a7c16dc69b29/edited.jpg)