Montgomery is the capital of Alabama. It is also a ghost town.

The trip from the airport to the city proper takes 20 minutes, and after you leave the freeway the traffic disappears and the ironies pile up. My taxi driver points out the home of Jefferson Davis, the only president of the Confederacy. A block later, we pass the Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church, where the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. presided between 1954 and 1960, followed soon after by the Alabama Confederate Monument. I'm reminded that this is a state where the day celebrating King is shared with Robert E. Lee, commander of the Confederate Army, and where the largest high schools, named for Davis and Lee, are 99 percent African-American.

Black and white photos of the civil rights movement had informed my vision of Montgomery: images of King entering the city at the head of a black voters' rights march in 1965; police dogs straining their leashes as African-American protesters emerge from a fog of tear gas; white people, their faces contorted with hate, yelling at women carrying signs demanding the integration of public schools. But on this evening in July, under a still bright-blue sky, the place is eerily quiet. My taxi passes meticulously preserved 19th-century homes, immaculate green lawns, stately, flowering trees. There's not a soul on the streets.

I get to chatting with the driver, an African-American who looks to be in his 60s. He tells me that he grew up and raised his children in Montgomery, that he loves it here, particularly the slow pace and the barbecue. He asks the reason for my visit. I explain that I'll be interviewing Bryan Stevenson, the lawyer, activist and director of the nonprofit Equal Justice Initiative. He nods in recognition. I ask if he's been to EJI's three-month-old National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which remembers the thousands of lynched African-Americans. "No," he says. "I don't need to go. I lived it." Has racism in Montgomery improved since his childhood? "A little," he says evenly, "but it will always be here. I don't expect that will change in my lifetime."

A few months into Barack Obama's presidency, Jimmy Carter told NBC Nightly News that he felt "an overwhelming portion of the intensely demonstrated animosity toward Obama is based on the fact that he's a black man." He got hammered by the media—America wasn't racist anymore!—but African-Americans knew what he was talking about. Bigotry had merely been pushed into the closet. And with the surprisingly successful campaign of Donald Trump, and his subsequent administration, that entrenched hatred emerged with a vengeance.

Nonwhite citizens of America grow up with an understanding: Even as racial discrimination has lessened, it remains embedded in our government, legal system and law enforcement. There is no post-racial America. There is, however, a neo–Jim Crow America. Consider the still segregated school districts, steering black children onto separate and unequal tracks (a 2016 report by the Government Accountability Office found the gains of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, which declared segregation of schools unconstitutional in 1954, have been almost entirely reversed); or that employment opportunities remain disproportionately stacked against people of color; or the relentless harassment of African-Americans by the police; or the prison population—the largest in the world—with its predominance of black and brown inmates. Systemic bias, it turns out, is as American as apple pie.

In his 1955 book, Notes of a Native Son, James Baldwin described America as having a "depthless alienation from oneself and one's people," and not "the faintest desire to look back." But the past, he went on, "is all that makes the present coherent, and further, the past will remain horrible for exactly as long as we refuse to assess it honestly."

These aren't black problems; they are the problems of a nation. As Baldwin also wrote, no one in America escapes the effects of racism, "and everyone in America bears some responsibility for it."

Roughly 65 years later, Stevenson is still making that argument, becoming one of the most prominent faces of the modern civil rights movement. Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption, his best-selling 2014 memoir (soon to be a film starring Michael B. Jordan), is an account of his decades of work as a lawyer representing poor clients wrongly convicted or excessively punished. The stories are horrifying and infuriating, but delivered with an unshakeable sense of hope and a belief that evil can be overcome.

Since EJI's founding in 1989, Stevenson and his staff, against tremendous odds, have overturned 135 death sentence convictions in Alabama and assisted in another dozen nationwide. They've taken four cases to the Supreme Court, two of them—Jackson v. Hobbs (2007) and Miller v. Alabama (2012)—resulting in landmark decisions: the abolishing of mandatory life without parole for children. And since 2008, EJI has expanded its scope to education, exposing a narrative missing from America's textbooks: A recent nationwide study revealed that, among other things, 92 percent of middle school students did not know slavery was a central issue of the Civil War.

In April, EJI opened two sites in Montgomery. The Legacy Museum depicts the history of black people in the U.S., beginning with slavery, through segregation, up to the systemic crisis of street-level harassment by police and mass incarceration. "Truth is not pretty, it's not easy," Stevenson will tell me, "but truth and reconciliation are sequential, so you need to get to the truth first."

The second site, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, informally known as the Lynching Memorial, remembers the more than 4,400 victims of racial terror lynchings in over 800 counties in 20 states between 1877 and 1950—sanctioned violence that forced 6 million black refugees to flee the South. Stevenson is not looking for financial reparations, like author Ta-Nehisi Coates, nor does he prioritize punishment, "but I do want to increase the shame index of America."

The memorial is a deeply moving step in that direction. But it also provides a bold bid for reconciliation. Each implicated county has a monument, and EJI is inviting those communities to claim and erect a duplicate where a lynching occurred—an offer that 300 counties have expressed interest in, and which will involved a deliberate process for claiming.

Stevenson's mission for reconciliation is more urgent than ever. Trump, who launched his modern political rise by questioning the legitimacy of Obama's presidency, won the 2016 election, in part, by casting racial and religious minorities as criminals and terrorists. When white supremacists marched on Charlottesville, Virginia, last year, a demonstration that resulted in the death of a counterprotester, he told reporters that there were "very fine people, on both sides." More recently, he warned that Democrats wanted migrants to "pour into and infest our country."

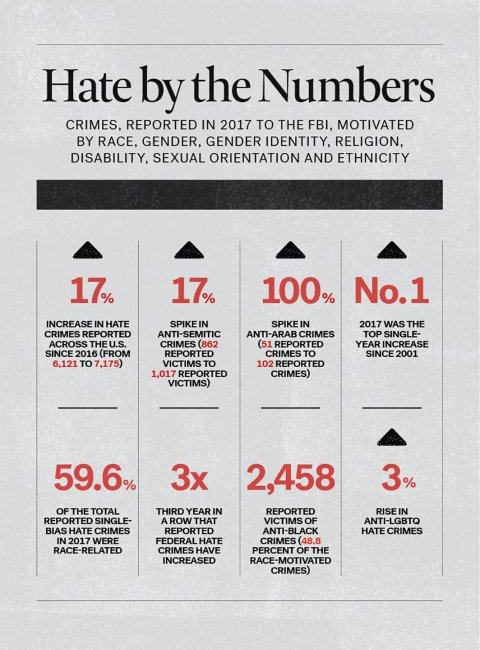

White supremacists have acknowledged that such rhetoric has inspired them to speak and act out in openly racist ways, and it has certainly reset the terms of acceptable discourse, at least in the Republican Party—chillingly demonstrated by November's midterms, including voter suppression and startling numbers of GOP candidates attacking minority opponents in nakedly bigoted terms. A week after the midterms, and three weeks after a shooter killed 11 in a Pittsburgh synagogue, an FBI report made all of this plain: Hate crimes rose 17 percent last year, with nearly three out of five motivated by race and ethnicity. African-Americans made up roughly half of all victims. The election of a biracial president felt like progress, but it's clear we overplayed the symbolism.

Lynching, it might shock you to learn, has never been classified as a federal crime. Passing a bill to abolish it would be a symbolic gesture of atonement, as well as a strong statement about the present and future. There have been dozens of anti-lynching bills introduced since the first in 1918, all of them aggressively opposed by members of the House and Senate. In June, Representative Bobby Rush of Illinois, and 35 members of the Congressional Black Caucus, introduced the latest, H.R. 6086. In doing so, Rush said, "you only need to look at the events in Charlottesville last year to be reminded that the racist and hateful sentiments that spurred these abhorrent crimes are still prevalent in today's American society."

As Stevenson likes to say: Slavery didn't end in 1865. It evolved.

"A PLACE THAT SILENCES YOU"

Stevenson is walking toward me, trim and smiling broadly as if an interview at 8:30 a.m. on an already steaming summer day is his idea of a good time. We've met at the entrance of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. "You're an optimist," I say, gesturing to his long-sleeved button-down shirt.

Three months after the memorial's April 26 opening, Stevenson is still marveling over its effect on visitors—20,000 in the first few days alone, and 30,000 in July. He tells me that people have been bugging him for a sequel to Just Mercy, and this, to his mind, is it—"another way of communicating to the world something I think we need to hear and see."

The memorial sits on six acres in Cottage Hill, what was, for generations, the heart of the black community. The women behind the yearlong bus boycott of 1955, a galvanizing moment in the civil rights movement, organized in this neighborhood. The Reverend Ralph Abernathy's church was here too.

In 1959, as black America was benefiting from worldwide attention for this movement, Sam Engelhardt—who had run for lieutenant governor on the campaign slogan "Segregation every day in every way"—was named director of Alabama's State Highway Department. By 1967, 1,700 homes, 75 percent of them black-owned, had been bulldozed to create Interstate 85, essentially boxing off the neighborhood from the rest of Montgomery and effectively erasing a civil rights incubator.

"That isolated and killed the community," says Stevenson of a strategy that was repeated in cities across America during the '60s. "The area fell into decline, with low-income housing, vice and drugs." Six years ago what was left of the neighborhood was razed. "Transforming this space back into something that has beauty and meaning, that represents this history," he says, "was really important."

The stunning site—a collaboration with Mass Design Group—has a Zen simplicity, with winding gravel paths featuring sculptures and poetry that contextualize racial terror. "Art can communicate things words lose," says Stevenson. A heartbreaking piece by Ghanaian artist Kwame Akoto-Bamfo features chained Africans being sold at auction. "We wanted something that revealed the anguish and brutality," says Stevenson, "but that was also human and had dignity."

He's been heartened by reactions to it. "A lot of people in their 50s and 60s have told me, 'You know, I've lived in this country my entire life, and I've never seen a sculpture about slavery.'" An institution, he adds, "that so profoundly shaped this nation."

Dixie pride—the celebration of the Confederacy and white supremacy—is communicated relentlessly in the South, with monuments, memorials and historical signs. It's worth noting that the majority were erected long after the Civil War's end, during the Jim Crow era, when racial subordination was codified, creating America's official system of apartheid. Such totems were pointedly placed in locations with political or judicial significance, like on courthouse lawns. And that scenario continues: In recent years, "heritage" laws have been passed in some states to protect these monuments. (Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, Florida and Georgia still include Confederate symbols in their flags.)

Over the years, Stevenson, who is 58, came to realize that holding America accountable for racial injustice extended beyond winning cases. As he and others have noted, the North won the Civil War in 1865, but it lost the narrative war. "We are taught a version of 19th-century history that is romantic," says Stevenson. "There's this false idea that things were so fantastic back in the '40s and '50s, or the early 19th century. We have a president who ran on the theme of make America great again. For black people, what decade is that supposed to be? When was it great?"

To see the endurance of this myth, look no farther than Roy Moore's extraordinary comment during his failed campaign for the Senate last year. Asked by a black voter when he thought America was last "great," the former chief justice of the Alabama Supreme Court fondly recalled the era of slavery: "I think it was great at the time when families were united—even though we had slavery. They cared for one another. People were strong in the families. Our families were strong. Our country had a direction."

But on the flip side, says Stevenson, excessive celebration of the achievements of the civil rights movement is problematic too, because "we think we accomplished more than we did."

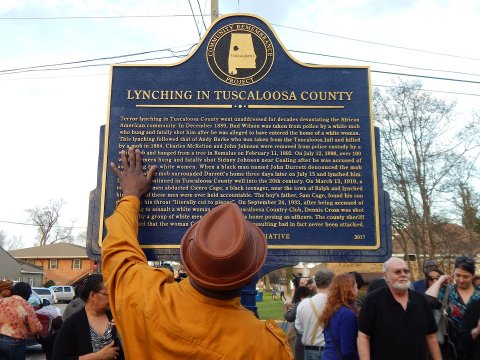

EJI is dedicated to eradicating such misconceptions. To that end, it has published three landmark reports on slavery, lynching and segregation; the 2015 lynching study raised the number of recognized victims by over 800 men, women and children. And thanks to the nonprofit's efforts, there are now three historical markers in Montgomery acknowledging the city's participation in the slave trade.

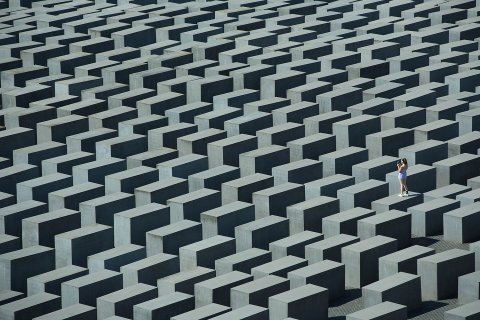

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice is a marker writ large—exposing not just Montgomery's and the South's participation in lynching but also the nation's. Plans for it began in 2010. Stevenson had visited Rwanda and South Africa. In both places, he was impressed by the commitment to acknowledging and detailing white oppression and genocide. The Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg, in particular, planted a seed. So, too, did a visit to the Holocaust Memorial in Berlin, an outdoor site of nearly 3,000 concrete gravestone-like slabs memorializing the millions of Jews exterminated during World War II. But he was also disturbed to see visiting schoolchildren climbing and running across the stelae, as if they were in a playground.

"When I got back, I said to my staff that I wanted to be very intentional in calling [the memorial] a sacred space," he says. "In our signage, we ask people not to talk loudly. And it's why we haven't allowed any video cameras or big equipment on the site. This is a somber place for reflection, much like Arlington [National] Cemetery—a place that silences you."

And devastates in equal measure. The violence you are faced with is scary and incomprehensible. "You'll see people—black and white—just weeping," says Stevenson. "The number one complaint the first week was: You need to have some Kleenex." They now order thousands of little packs.

The memorial structure is a winding colonnade sheltered from the sun but open to the air. The over 800 counties implicated in lynchings each have a visual representation, or monument, at the memorial—a 6-foot column with the names of the victim or victims etched into the surface. When you enter the colonnade, they are at eye level, "so you can see the names and read it and touch it," says Stevenson. "It gives you a sense of the arbitrariness of lynching, and how in some counties one or two people were lynched, in others dozens. They are almost like report cards on the communities."

As you make your way through the structure, the monuments begin to rise up: What look like large gravestones at eye level begin to resemble hanging bodies. "It's when they're above you that you begin to sense what it was like to live underneath this reign of terror," says Stevenson. "If there's been terrorism in America, this is it."

Terrorism, some maintain, should be applied only to political acts, like 9/11—an incident that lasted a single day and over which America went to war. But what is more of a political act than over a century of presidents, the Supreme Court and local governments condoning the systematic murder of its citizens?

"When you torture people in public," says Stevenson, "and don't allow the families to claim the dead because their bodies need to serve as warnings; when you drag their bodies behind cars, through black neighborhoods, for every person of color to see—that intention was to terrorize."

Such brutality is made plain in the CorTen steel used to make the monuments. Fiberglass was an early suggestion, but "it just didn't bring the gravity I thought this needed," says Stevenson. The steel, which arrives from the factory the color of silver, oxidizes in the air. In certain light they are brown; in shadow the color resembles dried blood. "It feels organic," he says, "as if there's something alive there. We wanted them to take on the feeling of bodies, particularly as you get deeper in."

Stevenson's father died last year. "I thought, My dad will look at this and say, 'They aren't pretty!'" He laughs. "But then I realized that wasn't what I wanted to achieve."

He is aware of the challenges in asking America to apologize to its black citizens. "You start talking about racial justice and people look for exits," he says. Still, it's no different than his clients going up for parole. "I tell them you're going to have to express remorse to the parole board or they're not going to trust you to go back on the street."

America, however, has never been good at remorse. In a society as punitive as ours, "where every mistake merits harsh punishment," says Stevenson, "apologizing means you did something wrong, and that implies that you're weak. But that's a critical part of recovery, that's how you heal."

Over 500 counties have yet to be soliticted by EJI. Some, I imagine, argue that it's best to put this hideousness behind us. Why open old wounds; what does it have to do with today? Because, Stevenson says, "we can't understand the police violence we are seeing, or sustained racial inequality, without understanding this history."

Is he hopeful about the new anti-lynching legislation before Congress? "I've been encouraged by the broad bipartisan support, yes," he says. "It's shameful that Congress has never said we have to stop this. It suggests that bigotry and discrimination and oppression are somehow OK."

Stevenson and EJI have received numerous death threats. The organization therefore took pains to keep the true purpose of the memorial's construction under wraps for as long as possible. Stevenson used a 2016 New Yorker profile by Jeffrey Toobin to announce the project. Toobin spoke to a local legislator to get his reaction. The notably hostile response: "They better not be getting any government money from this." Stevenson thought: Well, that's too bad.

And now? "Two weeks after the opening," he says, "I got a letter from that same legislator saying he was really moved by the experience of visiting and that he'd like to lead the effort to get the Montgomery [lynching] monument erected."

The success of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice appears to be softening hard-line feelings in Montgomery, a notably conservative city. The white mayor, Todd Strange, attended the memorial's grand opening, a two-day event featuring speakers and concerts by John Legend and Stevie Wonder. Strange "came up to me and said, 'Best night in Montgomery ever!'" says Stevenson. "And it couldn't have been more sincere. He just kept saying, 'Thank you.'"

"I NEVER SEEN A LAWYER WHO CARES SO MUCH FOR HIS CLIENTS"

The Alabama River winds through downtown Montgomery. At the foot of what is now Commerce Street, slaves would arrive in the holds of ships or in railcars. From there, they were marched along the avenue, to the warehouses where they were penned before auction.

Today, the gentrified street is filled with trendy restaurants and bars, the EJI building the only reference to its grim past. On a thin strip of grass, a historical marker identifies the site as the former warehouse of slave trader H.W. Farley. It includes a portion of an advertisement regarding the sale of a boy: "about fourteen," it reads, "very likely and sprightly."

Sia Sanneh, a senior attorney, has been with EJI for 10 years; she arrived when it was just 25 people and a copy machine. Now there are 60 full time staffers—including lawyers and the employees running the memorial and the Legacy Museum, which sits in the same immense former warehouse, its entrance a block away. "One of the misconceptions after Just Mercy, as Bryan's become more of a public figure," says Sanneh, "is that he is simply the public face of EJI. He's out there giving inspiring speeches, and meanwhile we're back here doing the work. But he is so deeply invested in every detail of what we do. He is always available."

EJI has roughly 250 cases, and Stevenson continues to meet with clients in prison, to argue in court and to work with those who have been released (there's an extensive re-entry program). There have been victories since Just Mercy, like the cases banning mandatory life without parole for children. Many of the young people Stevenson wrote about are now free, and a few work at EJI. Others have been resentenced and have a chance to get out.

"All my life I never seen a lawyer who cares so much for his clients," says Anthony Ray Hinton, one of Stevenson's greatest victories. On April 3, 2015, Hinton was released from prison after 30 years; he was among the longest-serving prisoners on Alabama's death row to be freed after presenting evidence of innocence—a conviction, argued Stevenson, that had everything to do with poverty, race and inadequate legal assistance. (His memoir, The Sun Does Shine, was an Oprah Book Club pick in June.)

Hinton has a booming voice, warm as a hug, and he tells me a story about Stevenson. When he was still in prison, the two would generally speak on Friday afternoons, after Alabama rulings are delivered. On this particular call, says Hinton, "I could tell by the way Bryan said hello that it wasn't good news. So I went into character; I said, 'Bryan, Ray had to go and this is Anthony. He told me to tell you to go out and have a good time this weekend. Have a nice dinner. See some friends. He'll call you on Monday.'" Stevenson laughed and said OK.

First thing Monday, Hinton calls him back. "Bryan's voice sounded stronger. He says to me, 'Please thank Anthony for his advice. I'm back on it now.' I got off the phone and thought to myself, What lawyer needs a person—let alone someone on death row—to give him permission to have a good weekend?"

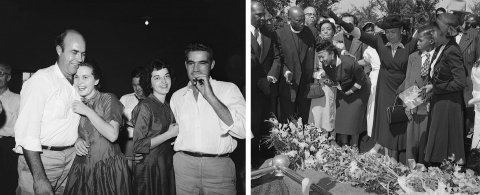

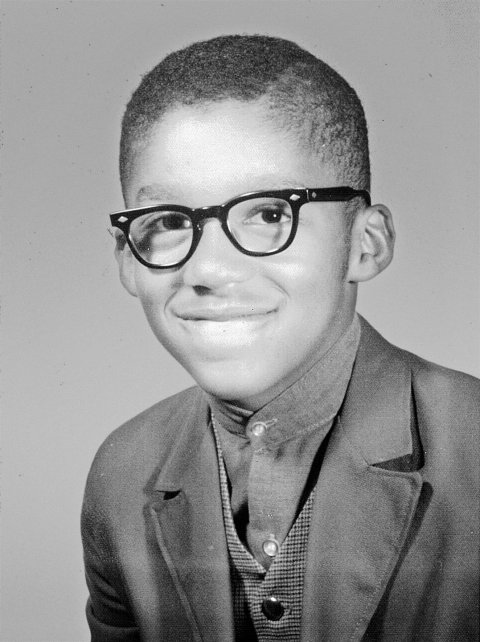

When I meet up with Stevenson again, in a conference room at EJI, I mention news I assume he'll welcome, reported in the paper that morning: The Justice Department had announced it will be reopening the Emmett Till case. Till, a 14-year-old boy, was falsely accused of whistling at Carolyn Bryant, a white woman, in Mississippi. He was subsequently tortured and lynched by her husband, Roy and his half-brother, J.W. Milam, in 1955 (She later recanted the most incendiary parts of her account). Till's death became a potent symbol of the civil rights movement.

But Stevenson tells me the news is generating mixed responses, and he is clearly not convinced the case needs to be reopened either. The killing was solved, he explains. Bryant and Milam were acquitted and, a year later, in an interview for Look magazine, confessed without remorse but could not be retried (both have since died). "If you were really going to reopen the case, you'd be asking, How is it that we refuse to hold people accountable when their guilt was so clear? And that's not an investigation into the crime," says Stevenson, "that's an investigation into our justice system, how it failed to protect black people, and why."

As guilty as the killers, he says, are the politicians, judges and law enforcement members who were speaking against integration and endorsing acts of violence through laws and rhetoric. "I can guarantee you that's not on the agenda," Stevenson says. "And that makes it a little self-serving—it creates a false sense of justice and closure and remedy." The publicity around the reopening of the case is also problematic "when we have all these shootings and horrific attacks which are of no interest to the Justice Department."

Troubling, too, is America's recurring response to racist acts. "There has been this dynamic in the South," he says, "where we want to reduce the ugliness of the hate and racial animosity to a handful of extremists—the Ku Klux Klan and the illiterate, poor white bad actors who can represent the sins of a nation or state. Prosecute them and we can feel good about ourselves."

Congress apologizing for its mistakes doesn't help the millions of people who have been, and continue to be, traumatized by systemic racism, of course. "But I do think institutions need to reconcile themselves to their own failures. Their decisions made it legal for slavery and the terrorism of African-Americans to exist following Reconstruction," he says.

There's a shadow, too, on the Supreme Court. Atonement might begin, Stevenson suggests, with a special opinion overruling Plessy v. Ferguson, the 1896 landmark decision that upheld the constitutional law of racial segregation (the doctrine that came to be known as "separate but equal").

EJI's battles for racial justice extend nationwide, but Alabama has particular challenges. Among them: Language in the state's constitution still prohibits black and white children from attending school together, even though it's not enforced. The only way you can remove that language is with a statewide referendum, which has been attempted twice. In 2004, 52 percent of the people in the state voted to keep it. In 2012, as Obama pursued a second term, the number jumped to 63 percent.

That, Stevenson believes, is directly connected to the stories we don't tell. "The narrative battle, for me, is the greatest challenge we face," he says. "If you don't have Martin Luther King Day but it's Martin Luther King/Robert E. Lee Day, you have a narrative problem in your state."

Why, I ask him, are Americans so resistant to the idea of one national story, as opposed to a divided narrative—white people and everyone else? Why, to this day, are issues related to minorities in America "their" problem and not "our" problem?

"If you go anywhere in the world where there is clear oppression or abuse of some group, or of women, or of different ethnicities, if you ask people to defend that oppression, they will give you a narrative of fear and anger," says Stevenson. "We saw that in America in the mid-1940s, when Japanese were put in concentration camps. We saw it when African-Americans were hanged and burned and drowned and beaten in the first half of the 20th century."

Fear and anger are powerful motivators, the scaffolding for abuse. It's a short hop from white slave owners equating Africans with godless animals; to 1930s politicians classifying blacks as uneducated, shiftless and dishonest; to Hillary Clinton labeling African-American youth "superpredators"; to President Trump tweeting about unpatriotic black athletes who bend a knee. That sort of rhetoric and propaganda, says Stevenson, turns citizens and law enforcement into foot soldiers of oppression, creating a reality where, among other things, African-Americans are 2.5 times more likely to be shot and killed by police officers.

"We may have stopped the public spectacle of lynchings," Stevenson says, "but by not expressing sorrow or holding the people accountable for that violence, there's this sense that you're never going to be held accountable for bigotry and racism."

"THE LION'S STORY WILL NEVER BE TOLD IF THE HUNTER TELLS IT"

Stevenson has a habit of smiling gently when delivering uncomfortable information—a useful tool for mediating the anguish and weight of true horror. "One purpose of it, I think, is to demonstrate to you that he's talking with you, not at you," says Vanzetta McPherson, a retired African-American judge who has known Stevenson for many years. "He knows who's to blame, but he isn't telling the listener that it's all his or her fault. It's easier to hear something when it doesn't have that baggage."

Watch his 2013 TED Talk (over 5 million views to date) and you see that strategic smile and a humility and empathy honed in the local Pentecostal church of his Southern Delaware hometown. His father, Howard Sr., a lab technician at General Foods, was the believer. "He had us in church all the time," says Stevenson's older brother, Howard (there's a younger sister, Christy, too). "He wanted us to pray for people who treated us bad. For my mother, you prayed afterwards."

The fierce, urbane Alice worked as an accounting clerk at the local Air Force base. Raised in North Philadelphia, she was forever appalled by the Deep South attitudes of Southern Delaware—particularly the deference shown to whites by African-Americans. "She would get upset if people treated us bad and we didn't respond in real time," Howard says. "Her approach was in your face. You don't let people demean you. You don't have to just swallow it. So we learned how to fight instead of avoiding these moments."

When Stevenson speaks, you can hear the push-pull of Howard and Alice. "I look at my brother now, the way he argues in court is similar to how my mother would argue in public," Howard says, "with a fire and fierceness that is unmistakable. But he also knows when to fight and when to persuade."

During McPherson's 15 years as a federal judge in Montgomery for the Middle District of Alabama, Stevenson never argued before her, but they've spent a lot of time commiserating about affairs in their city and in the criminal justice system. She admires his commitment not just to his clients, and to reforming the criminal justice system, but to creating an organization dedicated to telling the truth about African-American history to white and black people.

"Don't forget," says McPherson, "that we, like white Americans, went to schools with textbooks that absolutely avoided any accreditation of our history." The retired judge is 71, and this was true for her own books and those of her 44-year-old son. She suggests this may have changed.

It has not. For a new report, "Teaching Hard History: American Slavery," the Southern Poverty Law Center surveyed U.S. high school seniors, social studies teachers and 10 popular U.S. history textbooks used nationwide. Less than half of the books contained what the researchers considered a comprehensive examination of slavery or the enslaved, or made a connection between slavery and the Civil War. In a tiptoe in the right direction, the State Board of Education in Texas voted in November to change the way its public school students learn about the war: Beginning in fall of 2019, slavery will be presented as playing "a central role" for the first time.

But that move does not affect textbooks. Nor do they reference slavery's integral role in shaping our nation, financially and otherwise. (Recall the outrage over Michelle Obama's comment, in a 2009 speech, that she was living in a house constructed by slaves.)

Among the report's other revelations: Teachers, while serious about teaching the subject of slavery, are "uncomfortable" doing so. "Some adults refuse to tell children things because of their own fears, which is separate from what children can know and understand," says Howard, who is a professor at the University of Pennsylvania and director of its Racial Empowerment Collaborative, which counsels on education issues. Teachers and parents "use age as an excuse to avoid these topics," he says, "but the bigger issue is not the information, it's that we aren't teaching children to emote and feel and talk about things that are uncomfortable period."

Related to this discomfort is, as "Teaching Hard History" noted, the tendency to put the best spin possible on slavery, with focuses on feel-good stories about, say, the Underground Railroad. "Children's books, in particular, tend to be heroic, so kids have this misguided understanding around slavery being not so bad," says Howard, who has his own TED Talk. In it, he quotes an African proverb: "The lion's story will never be told if the hunter is the one to tell it."

Extend the lion metaphor to the people who design school curriculums. EJI has consulted on tests for the American Advanced Placement Exam. Eight or nine years ago, a question about Native Americans included the word genocide. "There was such a strong reaction from teachers against the word being invoked in association with what happened to Native people," Stevenson tells me, "that they pressured school boards to retreat from the question."

AP tests are created by the College Board, which also owns and publishes the SAT, long criticized for bias. All of these tests help determine school curriculums and how much time teachers devote to topics. If questions about Native American or African-American history are incomplete or don't exist, they are less likely to be taught comprehensively—or at all.

The Legacy Museum is a brick-and-mortar gesture toward filling that gap. In just 11,000 square feet, it depicts, with a visceral power, the history of black Americans. Most profoundly, it succeeds in making the case that, regardless of who you are, black history is your history. "One of the things that working here has made me more aware of is how the South and North have been deeply connected in this narrative," says Sanneh, who is African-American and grew up in Boston. "The history that created this climate would never have happened without complicity from the North and the federal government."

The museum draws a direct line from enslavement to convict leasing, a system finally receiving widespread attention (thanks in part to Douglas Blackmon's 2009 Pulitzer Prize–winning Slavery by Another Name). With the emancipation of slaves, hundreds of thousands of black men were arrested for petty crimes in the South, creating another unpaid labor force (roughly two-thirds of Alabama's 1898 state revenue was produced by convict leasing). The practice was phased out in the early 20th century—South Carolina was the last to prohibit it in 1933—but not before many of the prisoners perished under inhumane conditions.

When President Ronald Reagan declared his war on drugs in 1982, a new phase of enslavement and intimidation began: the modern era of mass incarceration. That, and mounting police violence against black and brown people, makes it clear this isn't a problem created by Southern conservatives. Racial injustice is a bipartisan issue. "Liberals are complicit," says Howard. "I wouldn't say one is as equally problematic as the other, but the demands are larger than what political conversations entertain."

One of the consistencies of racist ideology is that it's easy to undermine. Hinton had told me a story about confronting a member of the Klan in prison. "I said to him, 'Tell me why you hate me.' And Henry started to answer generally about black people. And I said, 'I didn't ask you a damn thing about blacks. I asked why you didn't like me.' He had no answer.

"I truly love talking to racist people," Hinton adds. "I say, 'You've been taught to have a cancer. Why in the world would you want to have that cancer?'"

The culture at EJI, as Sanneh had explained it to me, is shaped by Stevenson's faith that no one is defined by his or her worst act. "Dr. King believed that behind the violence and animosity and bitterness was a heart worth saving and inspiring," Stevenson says to me now. "And I've been moved and shaped by that consciousness."

It strikes me that, though we have talked about hate, he never uses the word to describe his own feelings. "Yeah, well, I just see it as something that burdens the person who is experiencing it more than the objects of it," he says. "Hatred will push you into violence and dark places where you can't love even the people you want to love. And once you're in that place, you've given up the most precious thing you get as human beings—the capacity to care for others."

Hinton now works for EJI, speaking regularly about racial injustice. Like Stevenson, and despite 30 years on death row for two murders he didn't commit, he seems to have bottomless reserves of hope and compassion. Hinton reflects on the audacity of racists telling him to go back where he came from—which would be Alabama. "Your ancestors did all of this to my ancestors," he tells them, "but yet I find room to love you."

"AMERICA WAS NEVER AMERICA TO ME. AND YET I SWEAR THIS OATH—AMERICA WILL BE!"

My taxi driver back to the airport is a black man who looks to be in his early 40s. He tells me that he came to Montgomery from Atlanta for his wife—a move he deeply regrets. What don't you like about the city? I ask. "Name something," he says.

I again explain the reason for my visit. He, like my first driver, hasn't been to the memorial or the Legacy Museum, but he's interested in why he should go. I tell him about the museum's section on convict leasing, which I had known little about, and its connection to mass incarceration today. This is news to my driver as well, and it reminds him of a recent fare, a man who had just been released after 16 years in prison. His father and son were still incarcerated—all convicted of separate nonviolent drug offenses—and they, too, would get out in a few months. "The guy told me it was the first time they would all be free at the same time," says the driver, "and the first time the grandfather would meet his grandson."

I mention this to Stevenson when we speak a last time, by phone, in late October. It's 7:30 a.m., and his voice is still froggy with sleep, but he jumps into the conversation with practiced energy. Ending mass incarcertation and excessive punishment in the United States is, of course, the commitment of EJI, as well as challenging racial and economic injustice. Alabama has the highest per-capita capital punishment rate in the country, and it remains the only state in the nation that allows a non-unanimous jury to impose the death penalty.

RELATED: Prisoners have the answers to our prison crisis, say Hank Willis Thomas and Baz Dreisinger

Stevenson had just argued his fourth death penalty case before the Supreme Court, Madison v. Alabama, a few weeks before we speak (Brett Kavanaugh had yet to assume the bench), and he was cautiously optimistic, even in this new era. "It's no secret that most of the decisions we've won were 5–4, with Justice Anthony Kennedy the decisive vote. Now that he's off the court," he says with his customary and strategic pragmatism, "the advocacy has to change."

After our interview, there seemed to be good news for EJI: Trump, after firing hard-line Attorney General Jeff Sessions, endorsed a bipartisan criminal justice reform bill. The First Step Act would reverse some tough-on-crime policies of the '80s and '90s—"a great start" when we "desperately need reform," EJI had said when the bill was announced.

The non-profit's views on the First Step Act continue to evolve. But other advocates have roundly criticized the legislation for not going far enough. Because Trump is famously fickle, it's hard to gauge the depth of his commitment to reform. He has expressed a desire to overhaul the system while granting clemency in a few high-profile cases, like that of Alice Marie Johnson, a 63-year-old grandmother serving a life sentence for a nonviolent drug offense. But he also campaigned on a law-and-order platform, and his administration has implemented policies that could drive, not relieve, mass incarceration. The true test could be in how he handles Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, who appears to be sidelining the bill in favor of other priorities in the final days of the legislative session.

What's clear is that Stevenson's message is beginning to break through. The memorial, he tells me, has been a greater success than he imagined, with over 300,000 visitors to date, and attendance is expected to rise dramatically in the spring, with EJI's formal effort to bring schools to the site. "I'd like to get every high school student in the state to come here," he says.

In mid-November, Montgomery hosted the U.S. Council of Mayors. Thirteen of them visited the memorial and spent over an hour with Stevenson. "To a person, they were awed," says Montgomery's Mayor Strange. "The conversation was around these hate crimes we're having throughout our country. I'm not going to tell you we're never going to have another one here, but I will tell you we're having a positive dialogue, with the memorial as a centerpiece." The conversation with Stevenson focused on "justice, mercy, love and compassion," Columbia, South Carolina, Mayor Stephen Benjamin said. "He touched the people, of every political persuasion, different faiths, different backgrounds."

Moments like that encourage Stevenson: "When people who have never seen a slavery sculpture finally see one, it changes them. People who didn't know about lynching now know about it. All of that will create a new relationship to those topics. I don't think it's too late."

But as hopeful as he remains, he is also clear-eyed about America's track record. Langston Hughes wrote the poem "Let America Be America Again" on a train ride in 1935. One stanza says,

"O, yes/I say it plain/America was never America to me/And yet I swear this oath—America will be!"

"Our forebears assumed everything gets better in time," Stevenson had said back in the EJI conference room. "That's obviously not true. If we stay silent for another generation, two other people will be sitting here in 50 years having the same conversation." — Additional reporting by Anna Menta