January 24, 2019; Colorlines and Texas Observer

Teen pregnancy is a problem. But the good news is that the rate of teen pregnancies in the United States has been reaching new lows…unless you happen to be a teenage girl in foster care in the state of Texas.

In the state of Texas, the rate of teen pregnancies of girls ages 13 to 17 in foster care is nearly five times that of their peers, according to a report from the nonprofit Texans Care for Children. The rate of teen pregnancies for girls in foster care is generally higher than the population at large. The National Center for Health Research reports that, “Teenage girls in the foster care system are twice as likely to get pregnant before turning 19 than teenage girls who are not in foster care.” But it’s clear the pregnancy rate among Texan girls who are in that state’s foster care system is extreme.

In looking for root causes, Texas shares challenges with other states that also have overworked and understaffed social service systems. Social workers making foster placements see their teen clients infrequently and rarely get enough time to establish relationships with them. This does not make talking about pregnancy prevention or sex easy. And when teens see their social workers infrequently, and shift frequently from placement to placement, an issue of trust comes into play. The same holds true for foster parents and guardians, who change frequently in the Texas system.

It is hard enough for teens to build trust when they are constantly being moved. Teens see their peers as their most reliable and consistent sources of information and advice. With no one to talk to, and those around them getting pregnant and having babies, teenage girls in foster care in Texas may see pregnancy as a way to join the crowd. As one teen said to Rebecca Grant, writing for the Texas Observer, “All my friends that I was in placements with—every single one—either has a kid or is pregnant right now.”

But in Texas, there is yet another barrier between teens and the information and resources that might help prevent teen pregnancies. That barrier is repercussions for adults who even discuss sex education, beyond abstinence, with a teen.

Adults in the system who do make sex-ed a priority can face repercussions. Six child-welfare professionals described to the Observer a prevailing culture of fear that they could be fired, delicensed, cited or sued for discussing sex or facilitating access to birth control or abortion.

“I know when I was a caseworker, I was so scared to talk about birth control and stuff with the kids,” said Mary Green, who now manages a youth center in Houston. “It’s scary, as the adult, to talk about with someone under 18 because of the rules, the laws.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Texas has become a hotbed for laws often inspired by the beliefs of the religious right. In 2017, Texas passed a law that allowed faith-based agencies with “sincerely-held religious beliefs” to act on those beliefs in their work. This allows for them to not discuss the use of contraceptives among foster teens. They can bar LGBTQ, Jewish, and Muslim adults from serving as foster or adoptive parents. And agencies that help frightened teens in their care obtain the morning-after pill risk losing state funding.

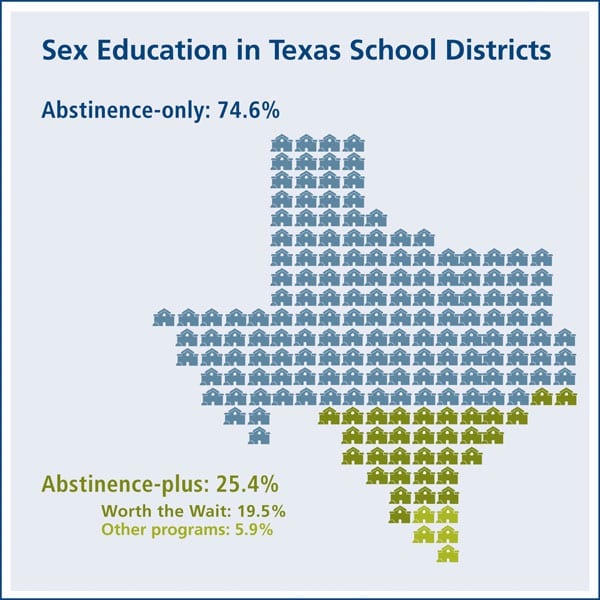

The myriad issues of sex education have been a political football for years at the local, state, and national levels. Texas has been part of this game, seeking funding for its abstinence-only programs and restricting what can and cannot be taught in schools. (NPQ reported on one highly successful pregnancy prevention program’s ups and downs during the “un-funding” in 2018.)

Race may be an added driver of the high pregnancy rate. While racial disparities in teen pregnancy rates have declined markedly since the 1990s, a gap persists, primarily because “teens of color are less likely to have access to quality health care and contraceptive services, and are much more likely to live in neighborhoods where jobs and opportunities for advancement are scarce,” according to Teresa Wiltz of the Pew Charitable Trusts. The racial breakdown of children in the Texas foster care system, according to a 2018 report from the Child Welfare League of America, indicated that 42 percent were Latinx and 21 percent were Black in 2015.

So, is Texas the perfect storm of an embattled system, with limited resources and restrictions on what can be taught about sex? Are there options? For one Texas judge, Darlene Byrne, who presides over placements in Travis County (county seat: Austin), a better tracking system of the individual foster teens’ sexual health would help her see how girls in foster care are doing and who is getting lost in the system.

The state has taken some steps to address teen pregnancy in the foster care system, such as incorporating reproductive health into its minimum standards and developing the PAL [Peer Assistance Learning] curriculum. Collecting data on the total number of pregnant and parenting foster youth also helps provide insight into the scale of the problem. The report from Texans Care for Children acknowledged these steps but found that “well-intentioned efforts have suffered from a lack of focus and follow through.”

Shortly after the report was released, DFPS [Department of Family and Protective Services] Commissioner Hank Whitman said in a statement that it was “based on misleading conclusions and flawed methodology.” He emphasized that foster care does not cause teen pregnancy and that the agency “continues to work to improve outcomes for all children in our care.”

But with one of the highest teen pregnancy rates in the nation, perhaps Texas needs to evaluate how well its systems are working. Social service systems, and not just those in Texas, must reassess how much time their social workers get with their teenage charges. Building relationships within foster placements that allow for accurate, up-to-date information on sex education and options for pregnancy prevention are crucial. Nonprofits should not fear loss of funding for providing young people with information and resources to make good choices.

The children in foster care in Texas deserve better, and those who entrust them to this system expect more.—Carole Levine