If I didn’t currently have a painful bruised rib (thanks, pick-up basketball!), the first thing I would have done upon reading a recent paper in JAMA Network Open was drop to the floor and start doing push-ups. It’s pretty much irresistible. The study promises a glimpse into the crystal ball, predicting your likelihood of future “cardiovascular events”—things like being diagnosed with clogged arteries or, say, dropping dead of a heart attack—based on how many push-ups you can do. How could you not be curious?

Researchers at Harvard Medical School and several other institutions analyzed health records from 1,100 male firefighters in Indiana who completed baseline physical tests between 2000 and 2007. One of those tests was how many push-ups they could do, to the rhythm of a metronome set to 80 beats per minute (one beat up, one beat down, meaning 40 full push-ups per minute), until they either gave up, fell behind the pace, had three consecutive attempts with incorrect form, or hit 80 reps. Their subsequent health was monitored for an average of 9.2 years after the baseline test, to see whether their push-up score predicted the likelihood of a cardiovascular event (of which there were a total of 37 during the study).

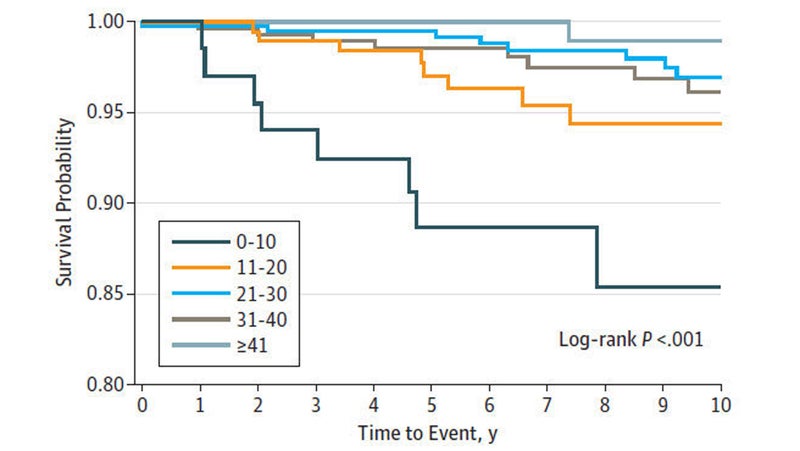

As you’ve probably guessed, the push-up score did indeed have predictive power. The headline result was that those who completed more than 40 push-ups were 96 percent less likely to suffer a heart problem than those who completed fewer than 10. That’s an enormous difference. More generally, each additional 10 push-ups tended to result in a lower risk, even after taking into account factors like age and BMI.

Here’s what the survival probability looked like over time depending on the number of push-ups subjects managed:

Given the small number of cardiac events, the relationship isn’t perfect: those who did 31 to 40 push-ups actually fared a bit worse than those who did 21 to 30. But the trend is pretty clear, and it’s very obvious that those who managed less than 10 push-ups were at significantly higher risk. (These numbers, unfortunately, are specific to men in their 30s and 40s like the firefighters in the study. As is so often the case, we’d need a broader study to figure out useful benchmarks for the rest of the population.)

Still, when my rib settles down, I’m eager to see whether I can eke out 40 push-ups at that 40-per-minute rhythm. It could go either way, but I suspect there’s a pretty good chance I’ll drop off the required pace somewhere around 30. Here’s the crucial question, though: if I don’t make it, but then spend a month or two focusing on push-ups so that I can hit 40 in 60 seconds, will I really have changed my long-term cardiovascular prognosis? Or will I have simply cheated—and thus invalidated—the test by cramming for it?

The reason the push-up test is interesting is because it’s simple, easily accessible, and free. There are plenty of other ways of assessing heart health, including treadmill tests, but they take more time, equipment, and money. As it happens, the firefighters in this study all completed a submaximal treadmill test that estimated their VO2max based on the speed they reached at 85 percent of their estimated max heart rate. This type of test isn’t as accurate as true maximal tests, where you go until you fall off the back of the treadmill, but it gives a decent estimate of cardiovascular fitness. Amazingly, in the firefighter study, the push-up score provided a slightly better predictor of cardiovascular risk than the submaximal treadmill test.

That doesn’t mean that upper body strength is the most important predictor of heart health, though. Instead, the push-up test has a lot in common with other tests of functional capacity. For example, there are dozens and dozens of studies showing that grip strength is a powerful predictor of future disability and death, including from cardiovascular disease. Same with self-chosen walking speed, and even, in older populations, the time it takes you to get up from a chair.

You can come up with arguments for why these tests make sense—maybe poor grip strength means you can’t get the peanut butter jar open, so you waste away. But overall, deliberately trying to improve any of those parameters probably isn’t the best way to go. In fact, there’s some evidence that typical strength training routines don’t improve your grip strength anyway. Instead, all of these tests likely reflect a larger constellation of healthy traits and behaviors: people who walk fast, have a crushing handshake, and can do a lot of push-ups probably tend on average to eat well, stay active, pay attention to their health, and so on.

So, by all means, check your push-up prowess. But remember that it’s just one among many indicators of your general robustness, along with others like, say, how easily you get injured while playing basketball. The best defense? Focus on the whole picture, rather than the details: do hard things, find new challenges, and don’t stop just because you’re getting older and feeling more fragile—because that’s a self-fulfilling prophecy.

My new book, Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance, with a foreword by Malcolm Gladwell, is now available. For more, join me on Twitter and Facebook, and sign up for the Sweat Science email newsletter.