It is a rare treat in any archive to be able to look at both sides of an international incident. Thanks to papers in the GFM series – which is largely underused and deserves more attention – I have been able to look at both British and German views on an espionage case in 1915.

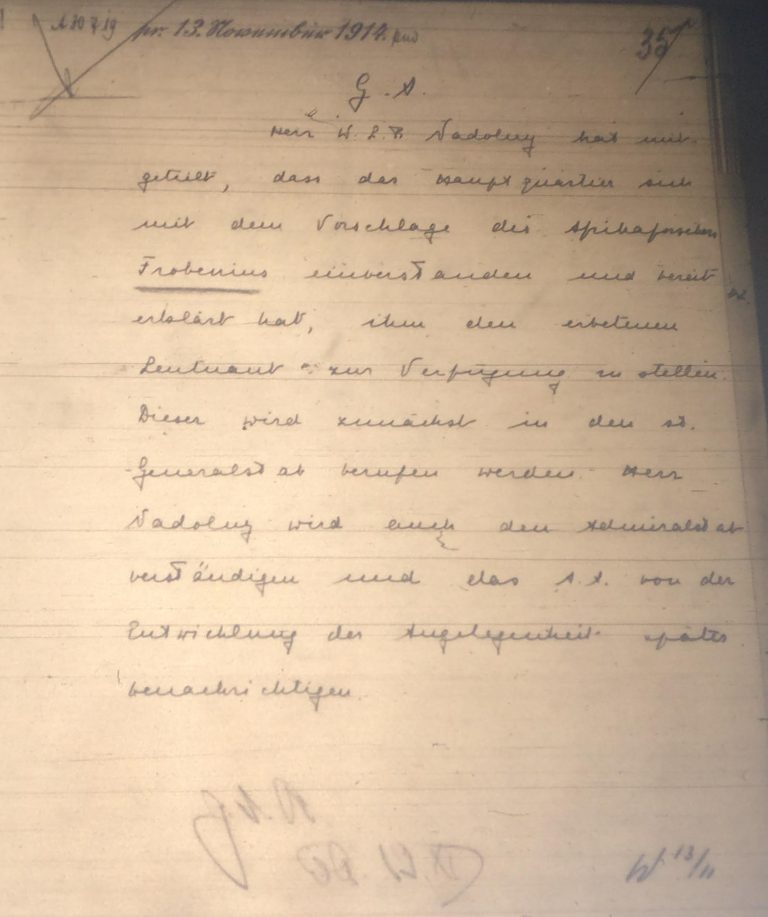

In November 1914, German ethnologist and adventurer Leo Frobenius was granted a rather generous sum of money to lead a mission to Abyssinia. The main objective was to convince the Abyssinians to renounce their neutrality and attack Britain in the Sudan, in order to make it easier for the Ottomans to attack the Suez Canal and Egypt (GFM 14/138).

Leo Frobenius’ mission approved, 13 November 1914 (catalogue reference: GFM 14/138)

Before he could set off for Africa, a few details needed to be ironed out. First, he needed a good cover story. The German Ambassador to Constantinople, Wangenheim, thought it would be a good idea to pretend he was delivering the post to the German Legation at Addis Ababa, Abyssinia, who were rather isolated.

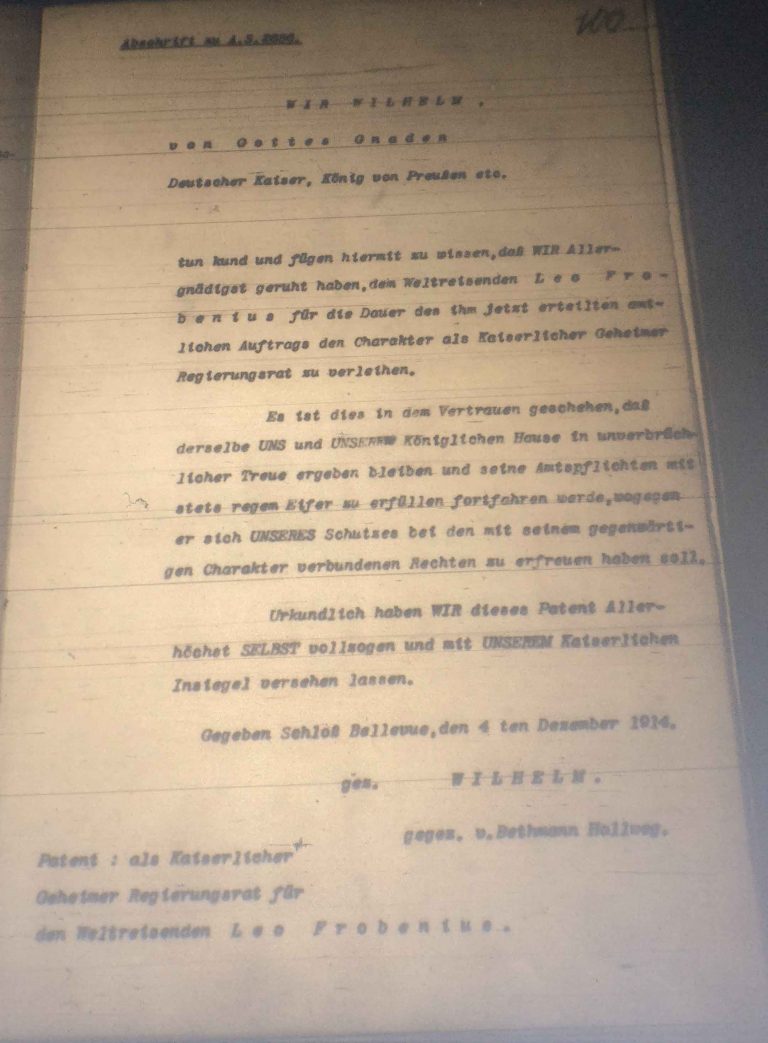

Frobenius also had to be given titles, to get more respect. He was appointed as Kaserlicher Geheimer Regierungsrat (Imperial Privy Council) on 4 December. He also insisted that he should be awarded Ottoman titles as he thought it would be most useful in Arabia. After much prevarication, the Ottoman Government agreed he could use ‘Pasha’ after his Arab alias, Abdul Kerim (GFM 14/138).

Frobenius’ appointment as Kaserlicher Geheimer Regierungsrat, 4 December 1914 (catalogue reference: GFM 14/138)

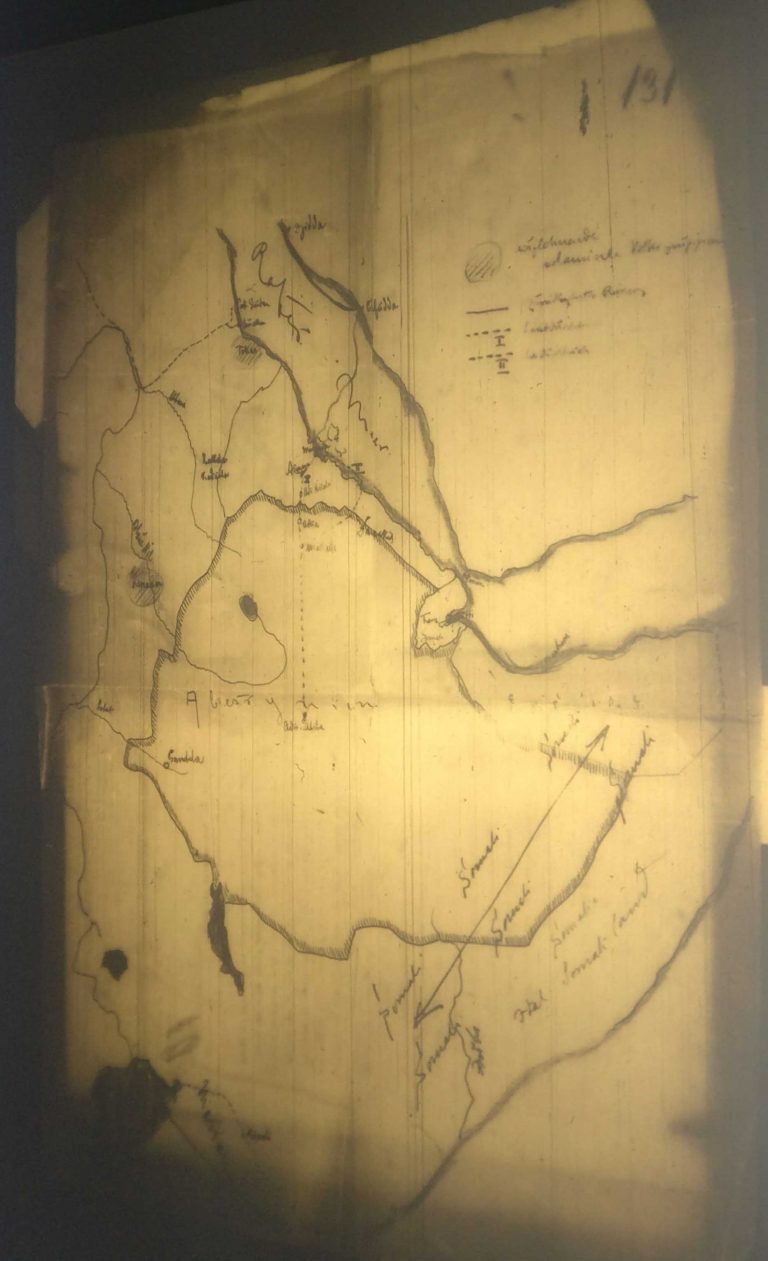

His route was a bit more straightforward to sort out. Leaving from Damascus, he would travel on the Hedjaz railway down to Al Ula, in Arabia, then reach Al Qunfudhah on the Red Sea, and cross to Massawa in Italian-controlled Eritrea, from where he would travel to Addis Ababa (GFM 14/138).

Leo Frobenius’ map (catalogue reference: GFM 14/138)

Frobenius gathered his team in Damascus in January 1915. There, having a bit of time to kill, they went to see ‘The Fall of Antwerp’ at the theatre.

Herr Frobenius described [in an interview given in April 1915 to an Italian newspaper] how the audience was convulsed with laughter at every mention of the activities of the British fleet (FO 371/2227).

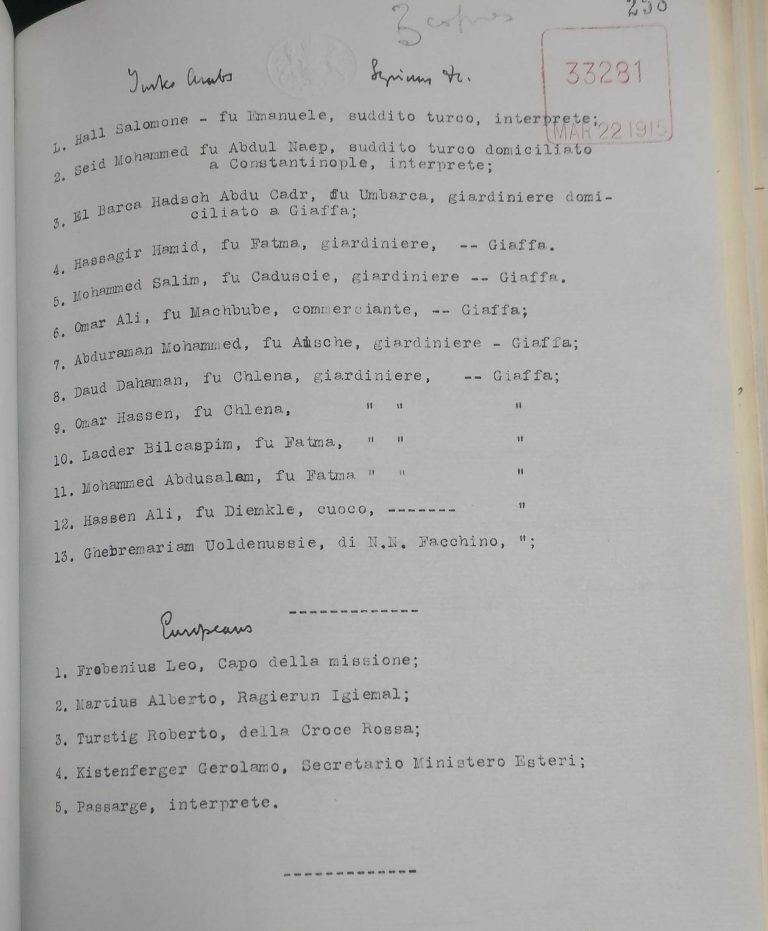

Having briefly stopped at Jaffa, in Palestine, to recruit most of the Arab members of the expedition (most of them were, for some reason, referred to as ‘gardeners’), Frobenius arrived in Al Ula on 15 January 1915. The mission members reached the Red Sea on camelback, and acquired a small dhow to sail along the coast to Al Qunfudhah, where they arrived on 7 February (GFM 14/138).

The members of Frobenius’ Expedition (catalogue reference: FO 371/2227)

Having rested and gathered supplies, they left for Massawa on 13 February. Frobenius was convinced that the British had known about the expedition since the very start. In the morning of 13 February, he woke up almost surrounded by enemy vessels. The dhow was stopped by the French cruiser Dessaix and searched by a French Officer, while Frobenius and the European members of his Mission were hiding under the deck boards. ‘He came so close to our knees,’ Frobenius reported, ‘that he could have touched them.’ (GFM 14/138)

Sir Rennel Rodd, the British Ambassador to Italy, commented: ‘The examination cannot have been very exhaustive’. He deplored the loss of ‘a good occasion (…) of obtaining the documents which they had brought with them for circulation in Africa’ (FO 371/2227).

The mission reached Massawa on 15 February.

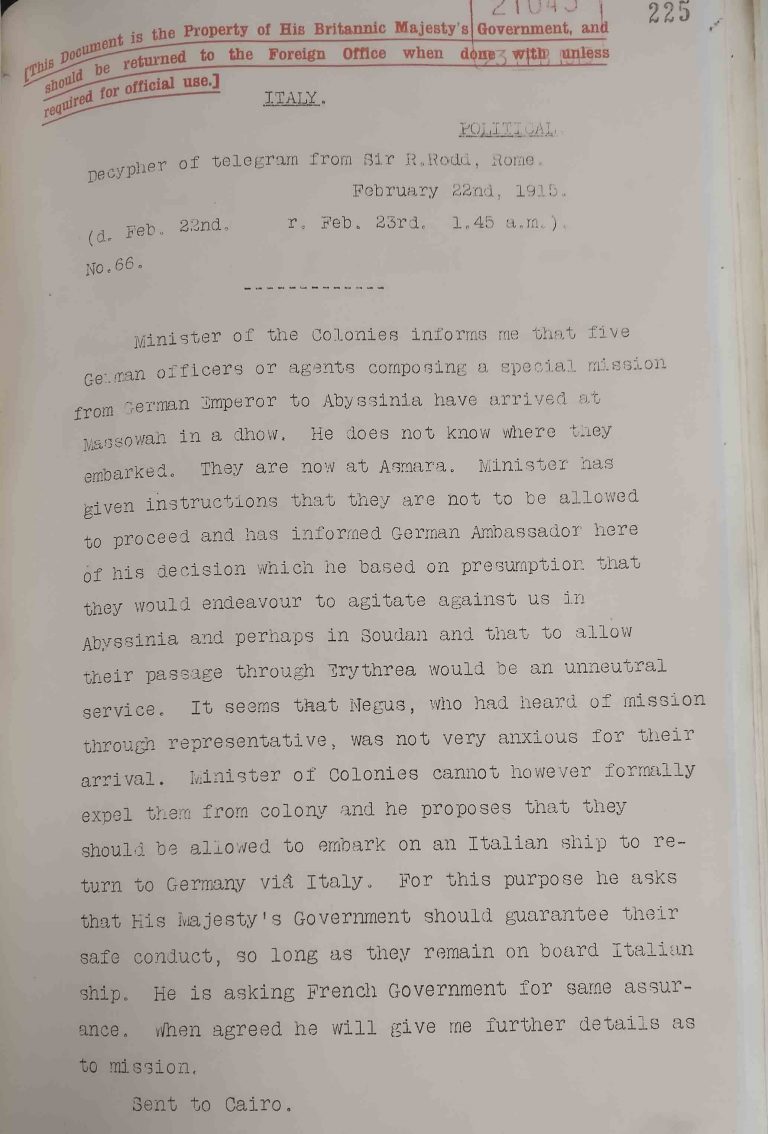

In Eritrea, Frobenius ran into a series of problems. While he had hoped he could cross into Abyssinia easily enough – especially as the Abyssinian government gave him permission to travel to Addis Ababa – the Italian Government declared that he couldn’t possibly travel through Eritrea ‘due to the general provisions in force during the war’ (GFM 14/138). Italy, still neutral at the time, had to tread carefully. The Minister of the Colonies informed Rodd, in Rome, of the presence of the Frobenius Mission in Massawa and added: ‘[allowing] their passage through Eritrea would be an unneutral service’. He suggested that the Germans should return to Germany via Italy on an Italian ship, for which the British and French governments should guarantee safe conduct.

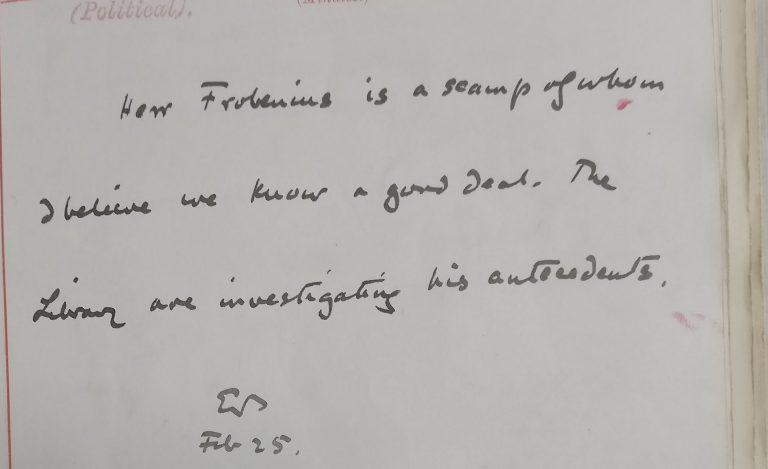

The Foreign Office commented: ‘Herr Frobenius is a scamp of whom I believe we know a great deal. The Library is investigating his antecedents.’ (FO 371/2227)

Rodd to Foreign Office, 22 February 1915 (catalogue reference: FO 371/2227)

Foreign Office minute, 25 February 1915 (catalogue reference: FO 371/2227)

Parallel discussions then started in Germany and between France, Britain and Italy, and lasted for about a month.

In Britain, all agreed that it was ‘extremely important that [the] mission should not be allowed to reach Abyssinia’, but there wasn’t much choice. On 25 February, the Foreign Office wrote to the Admiralty about the safe conduct:

Sir E. Grey feels it would be difficult to refuse such a safe conduct in view of the great service undoubtedly rendered by the Italian Government in stopping this mission which would otherwise have been able to do considerable harm in Abyssinia. (FO 371/2227)

The French Government agreed to the principle of a safe conduct on 28 February, but asked the Italian Government to provide a comprehensive list of the members of the mission, to make sure all the right people were sent back to Italy.

It was, however, more difficult than expected to get Frobenius and his team out of Africa.

It was agreed with the Italian government that the Germans would board an Italian ship; however, the first one available – postal steamship Porto di Abalia – couldn’t sail before 26 March. Frobenius, who had managed to make his way down to Asmara, suggested that ‘one of the party should return to Germany and report, and that the rest of the mission should remain and engage in archaeological and ethnographical studies’ (FO 371/2227).

In Rome, Rodd – who didn’t think Frobenius should be allowed to stay – talked to his German counterpart, Bernhard von Bülow. Bülow who, back in 1914, had asked for information and received very little, was not best pleased. ‘Not having been consulted and having no knowledge of the Mission’, Rodd wrote, ‘he was not particularly disposed to give it any assistance.’ (FO 371/2227)

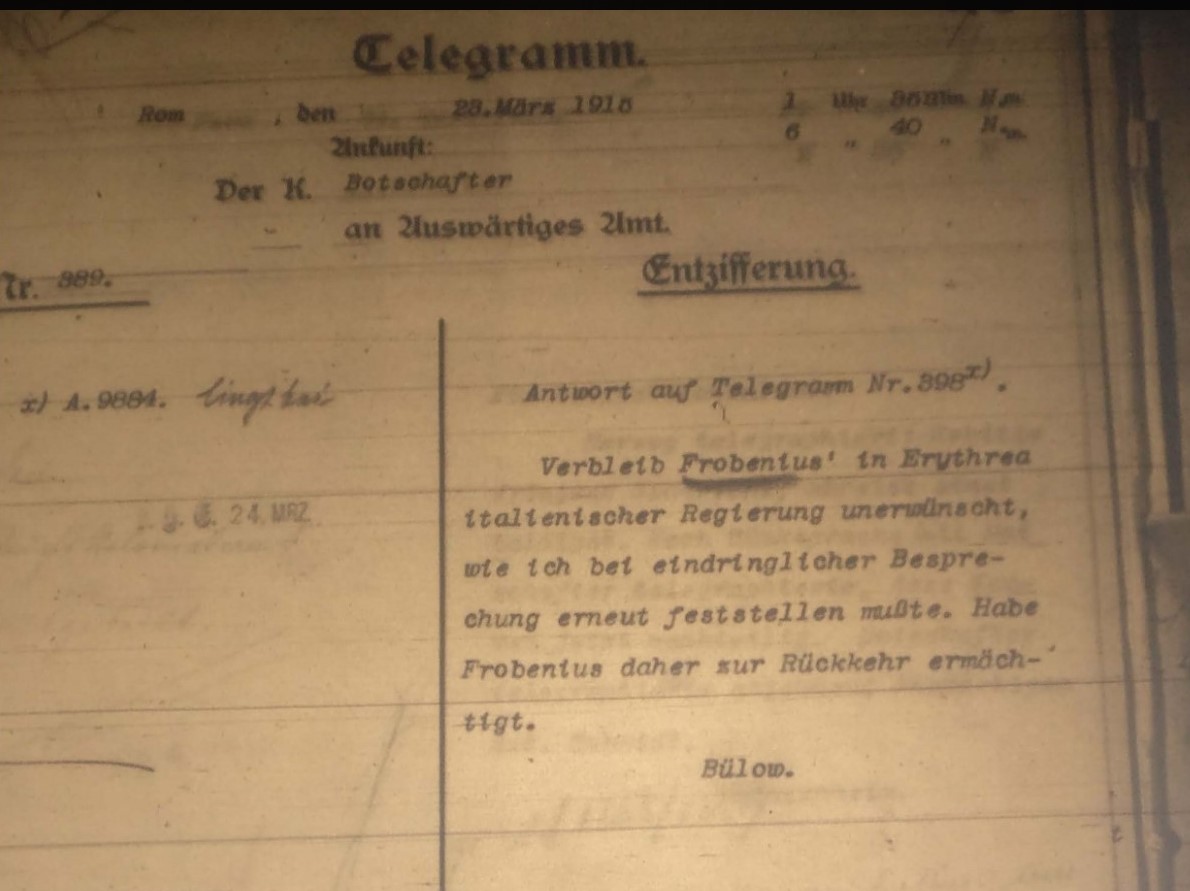

On 18 March, Bülow informed the Auswärtiges Amt that Frobenius and his whole team had to leave Eritrea ‘for political reasons’ and return to Germany via Italy. He wrote again on 23 March:

The Italian government does not want Frobenius to remain in Eritrea, which was once again made clear to me in an urgent meeting. I have therefore authorised Frobenius to return. (GFM 14/138)

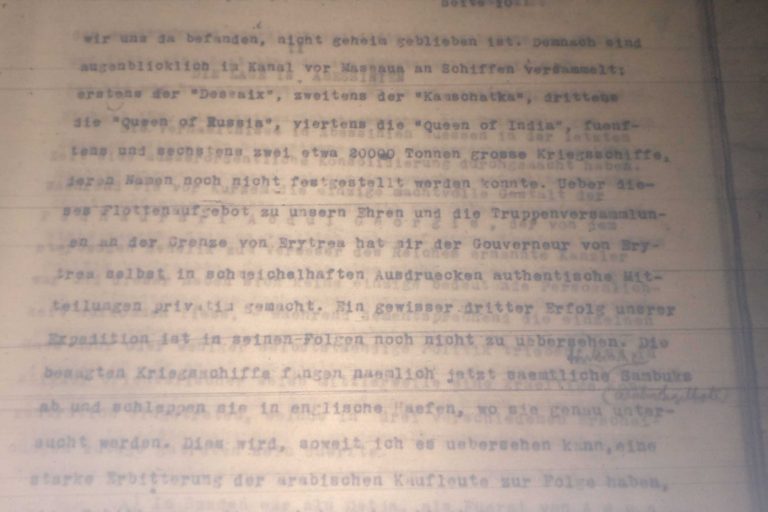

On the same day, Frobenius, always full of self-confidence, reported from Asmara that a lot of enemy ships were patrolling the Massawa canal and that troops were gathering on the border. He wrote:

I have been informed of this array of ships in our honour and of the mustering of troops on the border of Eritrea by the Governor of Eritrea himself […]. The possibility of a certain third success for our expedition cannot be ruled out yet. (GFM 14/138)

Frobenius’ report (Bericht) VIII, 23 March 1915 (catalogue reference: GFM 14/138)

Frobenius and his team finally left as planned, on 26 March 1915. Once in Italy, they started giving interviews. Much to the annoyance of Bülow and Wangenheim, Frobenius – who had initially denied having been involved in any kind of espionage activities – conceded that his own personal goal had been to ‘influence the Arab regions on behalf of the Ottoman Government’ (GFM 14/139).

He managed to cross into Austria just before Italy entered the war alongside Britain and her allies.

All in all, the Frobenius Mission was a disaster. First, its expulsion from Eritrea had a rather damaging effect on German prestige in the region (FO 371/2349), as well as in the Middle East where the ‘gardeners from Jaffa’, sent back to their hometown, spread the news of the German expedition’s failure (FO 371/2227).

Secondly, it put some strain on German-Ottoman relations. On 6 July 1915, Wangenheim reported: ‘The Turkish government has become extremely touchy regarding our various expeditions. Frobenius, in particular, has created great mistrust.’ (GFM 14/139)

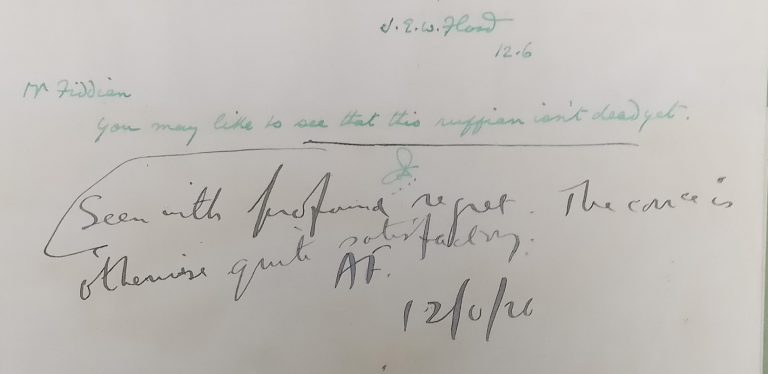

It also made it difficult for Frobenius to return to Africa. Long after the end of the war, in 1926, he expressed an interest in travelling to the Sudan to study desert tribes. At the Colonial Office, he was mostly remembered for smuggling antiquities out of Nigeria back in 1911. In June, Flood, of the West African Department, left a note for his colleague Alexander Fiddian: ‘Mr Fiddian, you may like to see that this ruffian isn’t dead yet.’ Fiddian replied: ‘Seen with profound regret’ (CO 533/621).

Exchange of minutes between Flood and Fiddian, June 1926 (catalogue reference: CO 533/621)

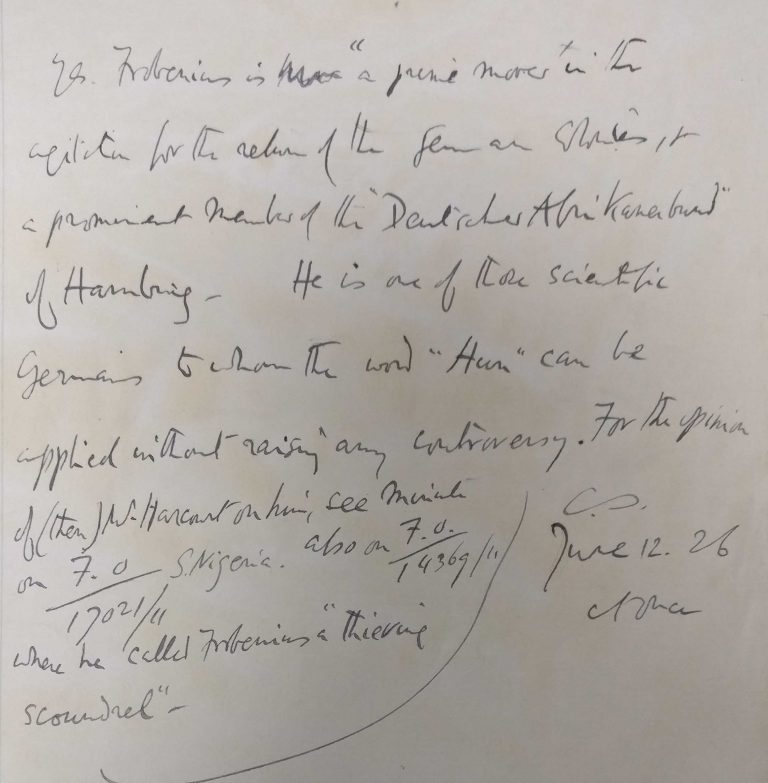

Sir Charles Strachey, the Assistant Undersecretary of State concurred rather vehemently: ‘He is one of those scientific Germans to whom the word “Hun” can be applied without raising any controversy.’ He added that Frobenius was generally regarded as a ‘thieving scoundrel’ (CO 533/621).

Minute by Charles Strachey, 12 June 1926 (catalogue reference: CO 533/621)

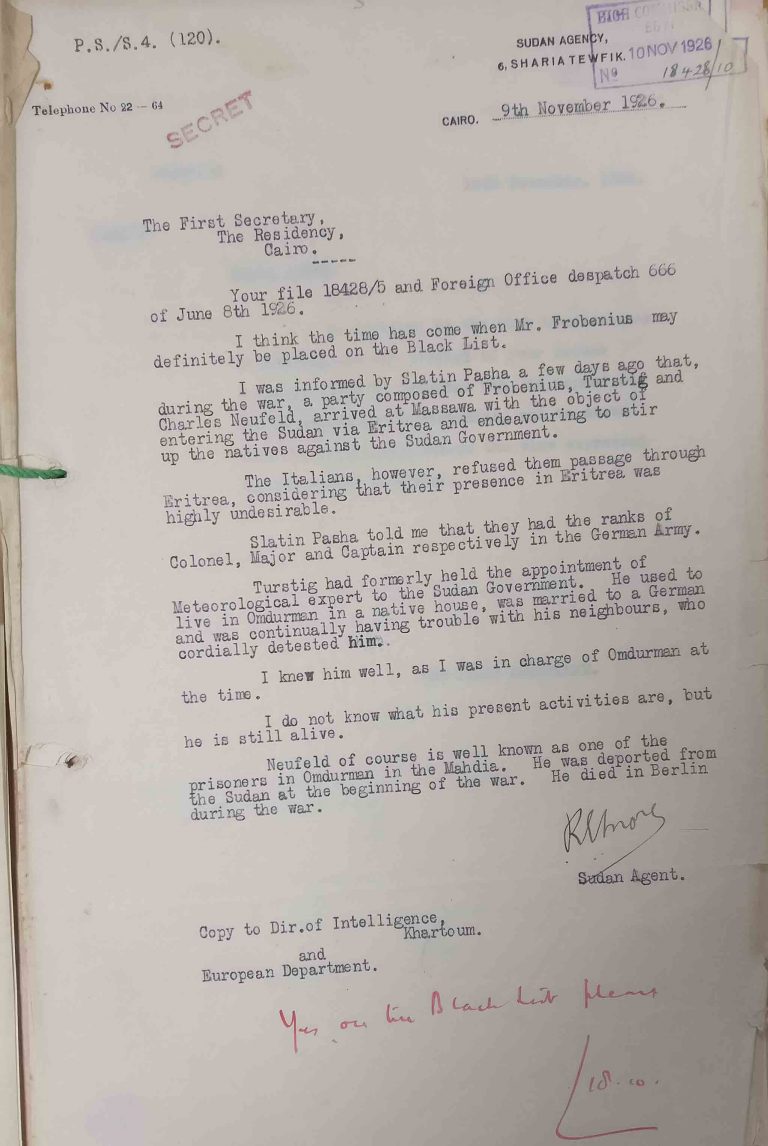

Frobenius wasn’t any more popular at the Foreign Office. In November 1926, the Sudan Agent noted: ‘I think the time has come when Mr. Frobenius may definitely be placed on the Black List.’ The First Secretary commented: ‘Yes, on the Black List please’ (FO 141/787/19).

Frobenius to be put on the Black List, November 1926 (catalogue reference: FO 141/787/19)

A year later, as Frobenius wanted to travel to the Union of South Africa and to the Belgian Congo via Northern Rhodesia, Strachey wrote:

I do not want to encourage his work, especially as his scientific reputation – which is the only reputation left to him – seems to be as second rate as his reputation for decent behaviour – now vanished. I daresay he is tamed now, Nevertheless, I would put every obstacle in his way that can legitimately be put there. (CO 822/3/12)

This was understandable, but a bit harsh. Frobenius had been sent to Abyssinia because he knew Africa very well, and was often described in German correspondence as ‘der bekannte Afrikaforscher Leo Frobenius’ – the famous explorer of Africa. His reports were incredibly pompous and, I suspect, not that useful, but they were well documented as well as verbose. Today he remains a major figure of German ethnography. Wangenheim, Bülow, the Ottomans and the British Government all agreed that he was a spy and a scoundrel, but we must concede that he was also a scholar.

For anyone who doesn’t know the GFM records are those of the German Foreign Ministry which were captured and copied at the end of the Second World War and the National Archives, Kew, have copies. They are interesting especially about the Second World War, needless to say most of them are in German.

I have previously only come across Frobenius as an explorer rather than as a spy.