Why Schools Need to Change

Reclaiming Education through Community Partnerships

Topics

Today’s learners face an uncertain present and a rapidly changing future that demand far different skills and knowledge than were needed in the 20th century. We also know so much more about enabling deep, powerful learning than we ever did before. Our collective future depends on how well young people prepare for the challenges and opportunities of 21st-century life.

A high schooler's perspective on why going back to normal, to abandon what this virus has revealed, will be to fail. We must transform, coming back stronger than before in every possible way.

Throughout the pandemic, and the consequential shutdowns, there is often talk of wanting to go “back to normal,” to fall back into the past, the thought of which provides us comfort and a sense of security, to forget COVID-19 ever happened. Though there is no doubt this pandemic must be fought, I beg that we do not return to “business as usual.”

To go back to normal, to abandon what this virus has revealed, will be to fail. We must transform, coming back stronger than before in every possible way.

I personally have found the school shutdowns to be extremely enlightening. High school has not treated me kindly, and I believe I speak for many students in saying so. Despite having been labeled a “smart kid” from a young age, I feel no more compatible with the traditional high school path than those who learn at a slower pace. We are all frustrated. Many of us are left behind or cast aside for wanting to move faster. Students often feel abandoned due to the limits set by the education system, limits which tell us how and what to learn. I by no means intend to speak against the notion of our standard subjects or say that there is nothing worthwhile happening in our schools. However, I do wish to make the case that we can do much better because we all have different interests and different minds.

I have lived my entire high school career aching for a subject which I have not yet touched, planning my college experiences around a major which I have never explored academically.

Quarantine and remote learning have taught me that I learn better with less guidance, that I thrive when given my own schedule and the ability to move at my pace. It has shown me a world I do not want to leave, in which I have control. My own interests—architectural engineering, calligraphy, and economics—are niche, and thus understandably I have less access to them. But high school has actively hindered my ability to explore anything about which I am passionate.

In my sophomore year, for a science project, I was asked to interview some professional architects and architecture students. Through this project I was told not how to access this subject and enrich myself, but instead that I “didn’t need to worry about it until college.” But I have lived my entire high school career aching for a subject which I have not yet touched, planning my college experiences around a major which I have never explored academically. I must go on the sole basis of this feeling in my bones that it is right for me, supplemented only by some books I have skimmed between classes.

Our entire grade was asked to take career aptitude tests, only for the results to sit in a portfolio. In a small school, only certain subjects can be accessed, and so students must carve their own mediocre path on the sidelines. All my interests, everything which sparks interest in my mind and my heart, are things which I must find on my own. Students are being asked to trust-fall into the world blindfolded.

That is why I joined the Peoples Academy Community Asset Mapping Team through the Vermont Community Learning Network. We were a small group of students taking the first steps toward a broader education system, one which will not be overwhelmed by the diverse interests of students. This, we believed, can be done if we only look beyond the walls of our school. When we reach out of our campus and into the community, not only can we accommodate students with unique career goals or different learning goals, but we can give students access to genuine experiences and connections which can be enhanced by a classroom.

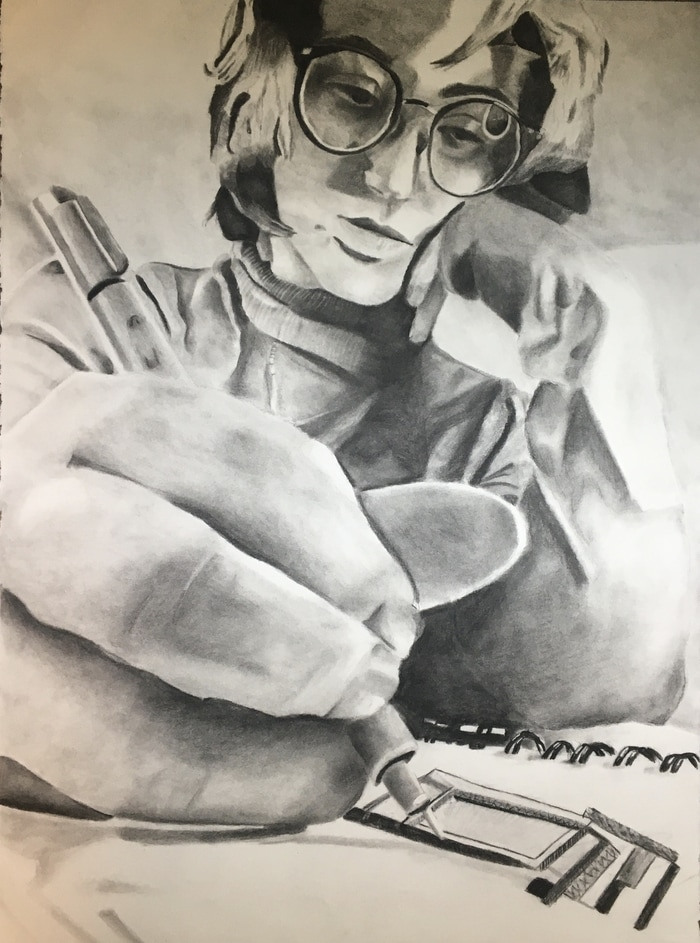

A charcoal self-portrait by the author.

We need to connect young people with those who share common interests and bring them to adults in their community who can guide them. The broader we allow students to reach, the easier it is to prepare them for the workforce, for their communities, and for the world. For the moment, these broader connections must be exclusively digital, but they may later lead to face-to-face relationships.

Remote learning presents us with a new opportunity to work with countless students like myself who feel out of place or forgotten in the public schooling system and even for adults hoping for new experiences. Those like myself who are now facing more free time and fewer interactions than ever before, who find themselves bored and even lonely, are craving new experiences which a community-based digital learning project can provide during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Not only will this greatly impact young lives, but it will improve the emotional, mental, and intellectual health of all involved through friendship, connection, and meaningful learning.

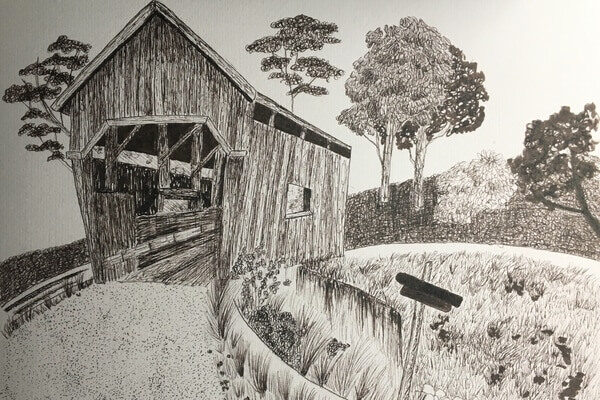

Image at top: A pen drawing by the author of a covered bridge.