On the surface, the equation seems simple: you sleep because you’re tired, and the more tired you are, the more you sleep. That’s presumably why athletes sleep so much: survey studies find that about half of national-team athletes are regular nappers. But a few months of stressed-out pandemic living offers a pretty stark reminder that being tired doesn’t guarantee that you’ll sleep well. And according to a new study, the link between training, fatigue, and napping in athletes isn’t that straightforward either.

The new findings come from researchers at Loughborough University, working with the English Institute of Sport, and are published in the European Journal of Sport Science. They invited three groups of 10 people (16 men, 14 women) to come into their laboratory and try to take a 20-minute nap: elite athletes, who averaged 17 hours of training per week; sub-elite athletes, who averaged 9 hours of training per week; and non-athletes. The key outcome was sleep latency: how quickly, if at all, would the subjects be able to fall asleep?

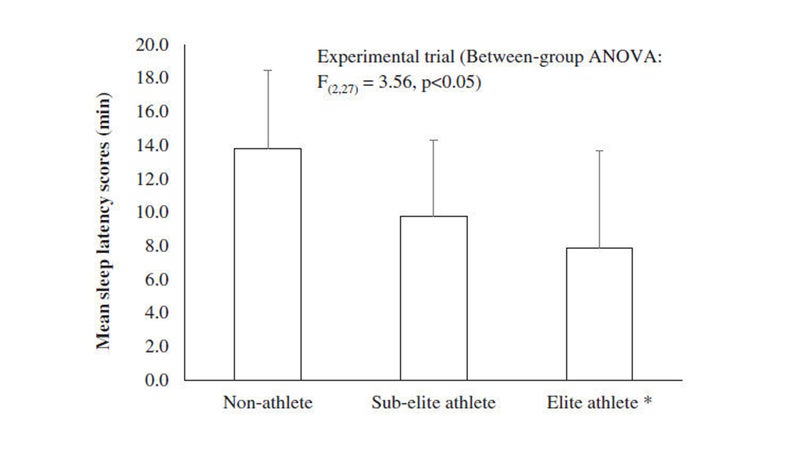

Let’s cut straight to the chase. As conventional wisdom would suggest, the elite athletes were quickest to fall asleep, the non-athletes were the worst, and the sub-elites were somewhere in the middle. Here’s what the average sleep latency times looked like for the three groups:

Any score below 8 minutes is considered to show a “high sleep tendency.” Just two of the non-athletes hit that threshold, compared to 6 of the sub-elites and 8 of the elite athletes.

But here’s the twist. The researchers also assessed how much each person slept the night before, and how tired they felt at 2:00 P.M., 2:30 P.M., and 3:00 P.M. immediately before the nap opportunity. Their sleepiness was assessed on a nine-point scale called the Karolinska Sleepiness Scale. And on these measures, there were no differences between the groups. The athletes got just as much sleep as the non-athletes, and reported virtually identical levels of sleepiness. They weren’t excessively tired—they were just really good at falling asleep.

The researchers link this finding to a concept called “sleepability,” which was first proposed in the early 1990s. Falling asleep quickly and easily is a skill, and some people are better at it than others. For example, it may be that athletes are better at managing levels of hyperarousal that interfere with sleep, or simply have lower levels to begin with. It’s interesting to think about the parallels between a cluttered, racing mind that keeps you awake, and a cluttered, racing mind that prevents you from hitting a free throw or running the perfect race. Elite athletes have to be able to turn off the latter; maybe that also helps them with the former.

It may also be that athletes are more used to falling asleep in unfamiliar environments, since they travel so much. To check that possibility, the researchers repeated the experiment twice to see if the results would differ once the laboratory environment was a bit more familiar. Both non-athletes and elite athletes fell asleep a few minutes more quickly the second time, but they improved by similar amounts, which suggests that the unfamiliar environment wasn’t the key driver. (The graph above is from the second trial.)

When you start digging into some of the references cited in the paper, you discover that there’s actually a long-running debate about why people do or don’t nap. A 2018 paper from researchers at University of California, Riverside suggested five different types of napping, which they summarized with the acronym DREAM:

- dysregulative: to compensate for shiftwork, illness, or exercise

- restorative: after poor or short sleep

- emotional: because you’re stressed or depressed

- appetitive: because it’s enjoyable, a habit, and you feel you do better with a nap

- mindful: to increase focus and alertness

Obviously there’s some overlap in those categories, and other papers use a simpler dichotomy between “appetitive” and “restorative” nappers, with the former defined as people who nap “primarily for reasons other than sleep need, and derive psychological benefits from the nap not directly related to the physiology of sleep.”

Our (or at least my) intuition suggests that athletes nap for dysregulative or restorative reasons: they’re really tired because they push their bodies so hard in training and can’t or don’t get enough sleep at night to compensate. The new Loughborough results argue instead that athlete napping is actually appetitive: they’re not excessively tired, but the naps make them feel like they perform better. Or to put it another way, they have low sleepiness but high sleepability. Intriguingly, previous research has found that appetitive nappers actually have better nighttime sleep quality and just as much sleep quantity as non-nappers, which is the opposite of what you’d expect if they were napping primarily to make up for inadequate nighttime sleep.

None of these studies address what we all really want to know, which is the magic recipe that will allow us to fall asleep instantly upon demand, anywhere, anytime. But they suggest a shift in how we think about naps. They’re not necessarily a warning that you’re failing to take care of yourself, or drowning in sleep debt. Sometimes they’re a sign that your mind is at peace, your body is at rest, and you’re lucky enough to have a half-hour to spare in the middle of the afternoon. Here’s hoping for more days like that.

For more Sweat Science, join me on Twitter and Facebook, sign up for the email newsletter, and check out my book Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance.