How Poetry Soothed a Nation in Mourning for John F. Kennedy

First the jolt of shock, then a shroud of sadness struck the nation in the weeks following that fateful day

:focal(1378x675:1379x676)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/71/fc/71fcca09-e7a9-42c1-b480-e78e1420f610/jfks_family_leaves_capitol_after_his_funeral_1963.jpg)

On that unsettling day 55 years ago this month, the nation began a pageant of tears. President John F. Kennedy was dead of an assassin’s bullet.

Schoolchildren were stunned to see strict and intimidating teachers weeping in the hallways. A Greenwich, Connecticut, mail carrier reported meeting a long line of sobbing housewives as he made his way from house to house. People lined up in front of appliance store windows to watch the latest news on a row of televisions. Before the four-day weekend had ended, more than a million had taken an active role in saying farewell to the president, and millions more had formed an invisible community as television linked living room to living room and brought almost every American within a big tent infused with unsettling questions.

Dazed citizens struggled to regain their equilibrium. Within minutes after gunfire stopped echoing in Dallas’s Dealey Plaza, this murder sent millions reeling, drawing them into a monumental event that would send a shock wave through the nation and create a commonwealth of grief.

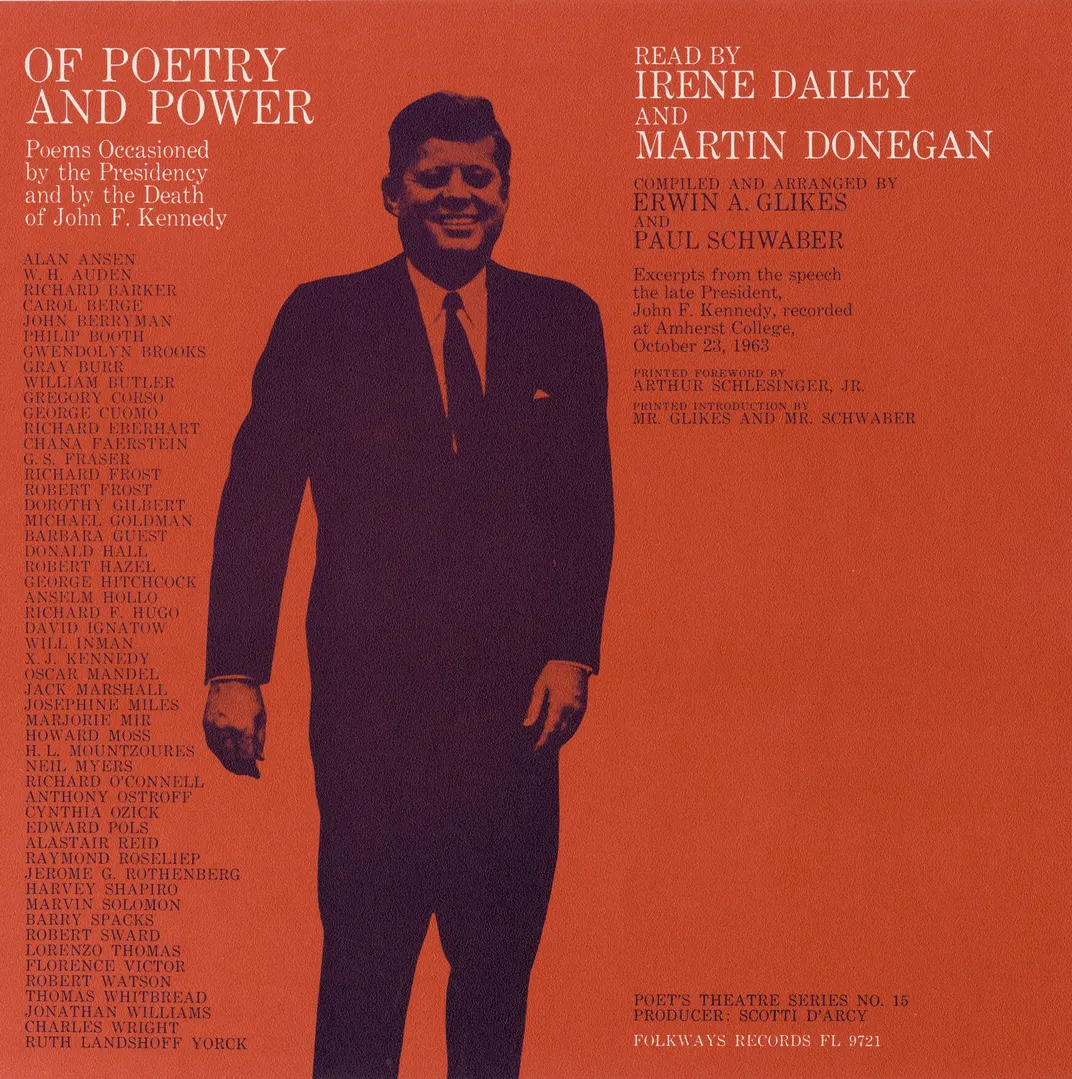

In the wake of Kennedy’s death, many newspapers published poetry tied to that weekend. Subsequently, editors Erwin A. Glikes and Paul Schwaber solicited poems about the assassination. Those works, along with some written during Kennedy’s presidency, were compiled into a book published in 1964 and an audio album recorded a year later. Both are entitled Of Poetry and Power: Poems Occasioned by the Presidency and by the Death of President John F. Kennedy, and the album’s tracks are available on Smithsonian Folkways. The album itself, with Irene Dailey and Martin Donegan reading the works, can be found in the Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections at the Smithsonian.

“There is a sad felicity in the fact that the murder of John Fitzgerald Kennedy should have provoked this memorial volume,” wrote historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr, in the forward of the album’s liner notes. Poetry played a prominent role in Kennedy’s vision of America. “He believed that the arts were the source and sign of a serious civilization and one of his constant concerns while in the White House was to accord artists a nation’s belated recognition of their vital role.” The poems, he noted, “convey the impact an emphatic man can have on his times.”

That impact was felt with paralyzing emotions in America’s homes and in its streets, as the nation—both Republican and Democratic—wrestled with an unrelenting sense of disbelief. Many could not imagine such a crime in the United States’ modern democracy. The last presidential assassination had been more than 60 years earlier when William McKinley had been slain in a nation existing before radio, television, automobiles and airplanes had revolutionized American life.

Charles Wright’s “November 22, 1963” captured the hollow shock in the streets of Dallas.

Morning: The slow rising of a cold sun.

Outside of town the suburbs, crosshatched and wan,

Lie like the fingers of some hand. In one

Of these, new, nondescript, an engine starts,

A car door slams, a man drives off. Its gates

Bannered, streets flagged and swept, the city waits.

JFK had been the first president to conduct live televised news conferences, so he visited American homes frequently in an informal capacity. His intelligence and wit permeated both popular and political culture. While what he said was no more profound than the words of wartime leaders like Abraham Lincoln and Franklin Roosevelt, television made him more familiar; his connection, more personal. He still holds the highest average approval rating—70.1 percent—since the Gallup Poll began collecting this data more than 70 years ago. Furthermore, American historians’ most recent rankings place him as the eighth best president and the sole leader in the Top Ten to serve less than a full term.

In concise, sharp phrases, poet Chana Bloch marked JFK’s absence from the airwaves in “Bulletin.”

Is Dead. Is Dead. How all

The radios sound the same.

That static is our seed.

Is dead. We heard. Again.

More like something out of a dream than a part of daily life, that weekend indelibly imprinted scenes in American memory: the riderless horse, the rat-a-tat-tat of the muffled drums, the brave widow, the toddler saluting his father’s casket. The televised murder of the apparent assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald, by Jack Ruby reinforced the sense of unreality. What is often absent from American memory is the near-universality of the shared bereavement and the wide range of emotions that struck even those who had been Kennedy’s opponents but never expected his presidency to end like this. When he was gone, few found joy in his absence. The shock, the tears, the shame engulfed America.

Poet Cynthia Ozick portrayed the politics of death in “Footnote to Lord Acton,”

The forgotten speaker,

The alternate delegate,

The trampled demonstrator,

The shunned and shunted eldest statesman with his honed wail unheard,

How irrelevant is death to the pieties of men!

Death the dark, dark horse.

And Robert Hazel, explored the unimaginable grief of the widow and her children in “Riderless Horse:”

Above the muffled drums,

the high voice of a young soldier

tells the white horses how slow to go

before your widow and children, walking

behind the flag-anchored coffin—

and one riderless black horse dancing!

When Air Force One returned home to Andrews Air Force Base about five hours after Kennedy’s death in Dallas, family, friends and officials were there to greet Jacqueline Kennedy, the casket and the nation’s new president, a shaken Lyndon B. Johnson. However, these dignitaries were not alone. Hidden in the darkness behind a fence stood 3,000 anonymous Americans, largely unseen. During the autopsy at Bethesda Naval Hospital, thousands more entered the hospital grounds. When the body finally left Bethesda on its way to the White House at around 4 a.m. on November 23, author William Manchester reported that members of the official party saw “men in denim standing at attention beside cars halted at intersections, and all-night filling station attendants were facing the ambulance, their caps over their hearts.” Unofficial cars joined the ghostly caravan to the White House.

The palpable grief for the young dead father and husband is painted vividly and gruesomely in Richard O’Connell’s “Nekros”

A head dropped back and dying

Pouring blood from its skull . . .

All history stark in that flow

The next day, the family and close friends remained mostly hidden within the White House, planning a well-choreographed, unforgettable funeral while confronting the first awkward moments of the transition from a young, clever and eloquent president to a plain-speaking, drawling Southerner who practiced the in-your-face, in-your-space politics of friendly intimidation. Johnson was a consummate politician, something Kennedy was not, and the new president possessed none of the intellectual aura and glamour that surrounded his predecessor.

On Sunday, the mourning again invited public participation. Late that morning, Washington sidewalks filled with 300,000 Americans gathered to watch a caisson deliver the president’s body to a funeral bier in the Capitol. At 3 p.m., the stately palace of the nation’s lawmakers opened its doors to a constantly replenished stream of 250,000 Americans, some waiting in line ten hours, to walk past the catafalque and say their goodbyes. On Monday morning, 5,000 people waiting in line were turned away. Preparations for the funeral had to begin.

Poet David Ignatow fled ritual, seeking reality in “Before the Sabbath”

Good father of emptiness,

you keep saying over and over

in the birth of children

that we are not born to die,

but the mind is dulled,

for the man is gone on a Friday

before the Sabbath of the world remade.

Smiling, he is dead,

too quickly to explain.

More than a million lined the capital’s streets to see the coffin travel from the Capitol to the White House and then stood amazed as international figures such as French General Charles de Gaulle and Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie followed Jacqueline, Robert and Edward Kennedy in a walk through the streets to St. Matthew’s Cathedral where the funeral Mass occurred. Afterwards, a line of official cars passed crowded sidewalks as it followed the casket to Arlington National Cemetery.

The stark rhythm of that moment resonated in William Butler’s “November 25, 1963”.

Drums, drums, I too am dead.

I breathe no breath, but only dread.

I have no soul, but lay my head

Upon his soul, and on that bed

I stop.

Audiences at home had a more intimate view inside the Capitol, within the cathedral and at the cemetery, where the Kennedys lit the eternal flame. The Nielsen ratings estimated that the average American home tuned into assassination-related events for 31.6 hours over four days. Many American children attended their first funeral when they watched services for JFK. Even to most adults, the Latin funeral Mass for the nation’s first Roman Catholic president was something new.

John Berryman’s anger at the senseless loss erupted in his “Formal Elegy”

A hurdle of water, and O these waters are cold

(warm at outset) in the dirty end.

Murder on murder on murder, where I stagger,|

whiten the good land where we have held out.

These kills were not for loot,

however Byzantium hovers in the mind:

were matters of principle—that’s worst of all—

& fear and crazed mercy.

Ruby, with his mad claim,

he shot to spare the Lady’s testifying,

probably is sincere.

No doubt, in his still cell, his mind sits pure.

Smithsonian Folkways sprang from a decision to acquire “extinct record companies” and preserve their work, according to Jeff Place, curator and senior archivist of Folkways. Moses Asch, Folkways founder, wanted to create “documentation of sound,” Place explains, and he wanted to share the sounds with a broad spectrum of the population rather than serving as an archive. Understanding the written materials that accompanied each recording plays a vital part in the process.

The spoken poems written about JFK’s death fit into the Folkways collection well, Place says. Folkways has other documentary recordings on topics including the U.S. presidency, the Watergate scandal, the House Un-American Activities Committee and other political themes.

As the texts within Of Poetry and Power reveal, JFK’s assassination struck a raw emotional chord that still rasps through the nation’s psyche. Trust in government has collapsed since his death. The Pew Research Center’s survey for 2017 showed only 3 percent believed the government could be trusted to do the right thing “just about always” and just 15 percent believed the government could be trusted “most of the time.” Trust hit an all-time high of 77 percent in 1964 as Americans clung to Lyndon Johnson like a sinking ship in featureless ocean; by 1967, distrust inspired by the Vietnam war—and growing belief in an assassination conspiracy—had begun to take hold.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)