Recently, I found a typo in the District of Columbia’s legal code and corrected it using GitHub. My feat highlights the groundbreaking way the District manages its legal code.

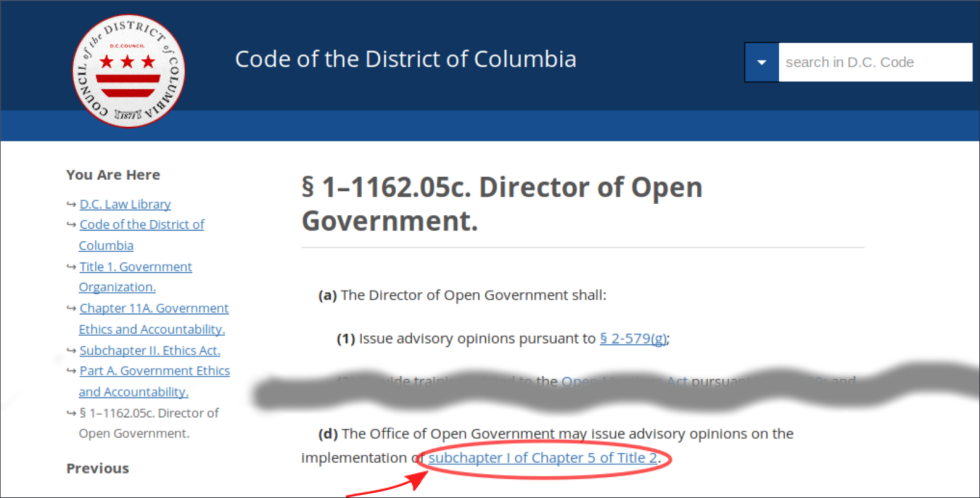

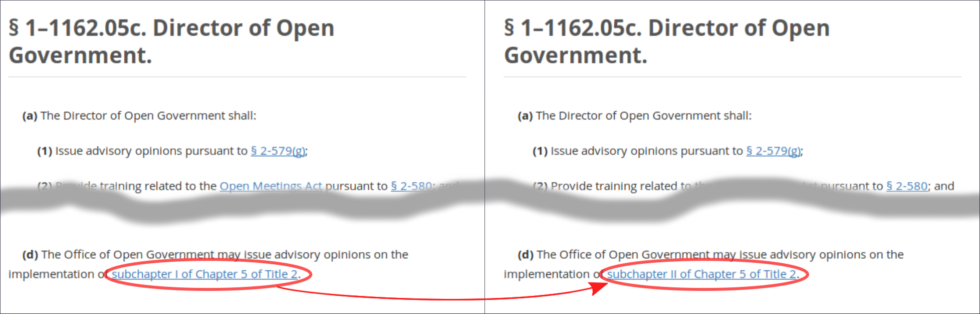

As a member of the DC Mayor’s Open Government Advisory Group, I was researching the law that establishes DC’s office of open government, which issues regulations and advisory opinions for the District’s open meetings law (OMA) and open records law (FOIA). The law was updated last month, and something seemed to have changed: there was no longer a reference to issuing advisory opinions for FOIA. Comparing the DC Code to the act that made the change, I noticed that something was amiss in section (d):

(d) The Office of Open Government may issue advisory opinions on the implementation of subchapter I of Chapter 5 of Title 2.

It had a typo.

Subchapter I of Chapter 5 of Title 2 of the DC Code is about how the DC government makes regulations. FOIA is subchapter II, not subchapter I. In other words, the link to “subchapter I of Chapter 5 of Title 2” took visitors to the wrong part of the law.

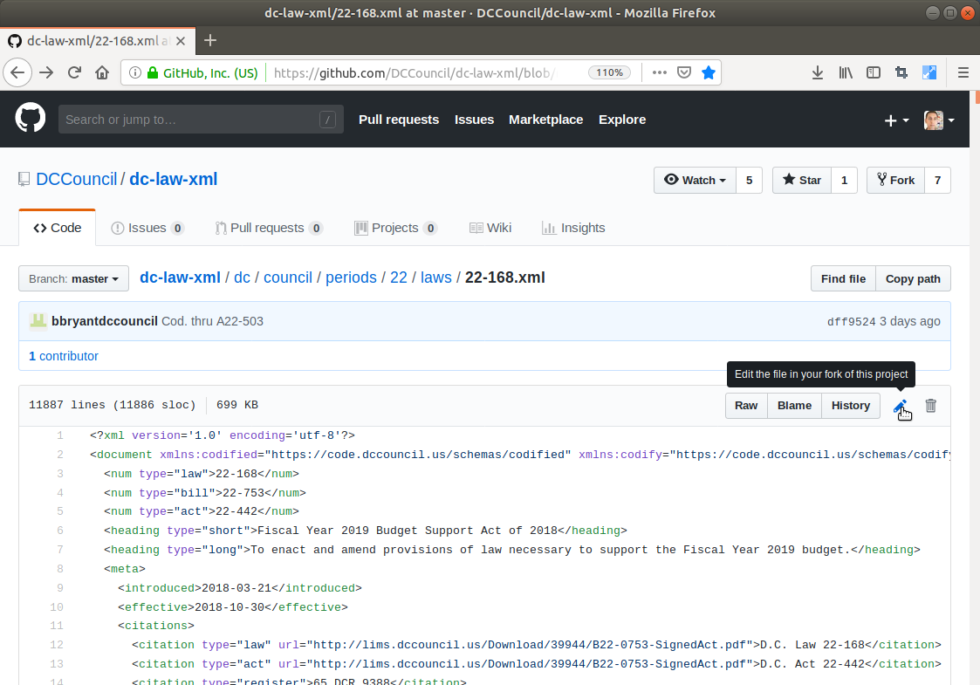

The District does something with its legal code that no other jurisdiction in the world does (to my knowledge): it publishes the law on GitHub. GitHub is a website used primarily by software developers to share and collaborate on software code.

Lawyers and engineers noticed in the early part of this decade that lawmaking and software engineering have a lot in common when it comes to tracking changes to their code—whether it be legal code or software code. The District has managed to take a practice of modern software development and apply it to its legal code by putting its legal code onto GitHub at https://github.com/DCCouncil/dc-law-xml.

This isn’t a copy of the DC law. It is an authoritative source. It is where the DC Council stores the digital versions of enacted laws, and this source feeds directly into the Council’s DC Code website at https://code.dccouncil.us/dc/council/code/.

Last week, I opened the file on GitHub that had the typo, edited the file, and submitted my edit using GitHub’s “pull request” feature. A pull request is a request to the file’s maintainer to review a change and then, if approved, pull it in to the main file:

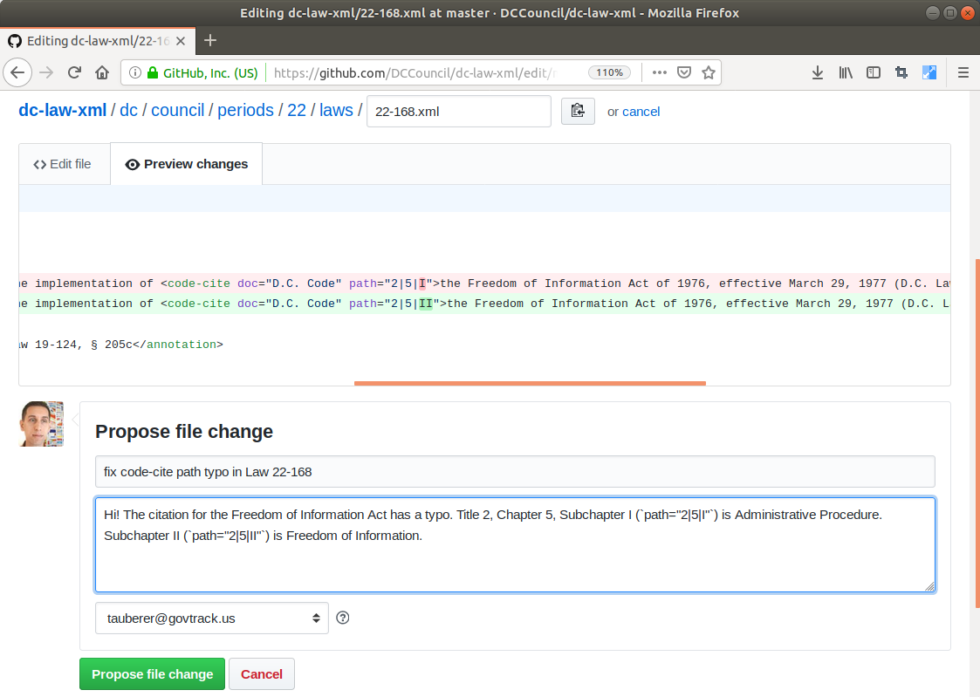

Here I’m editing the file and changing the roman numeral “I” to “II” in the XML markup of the citation:

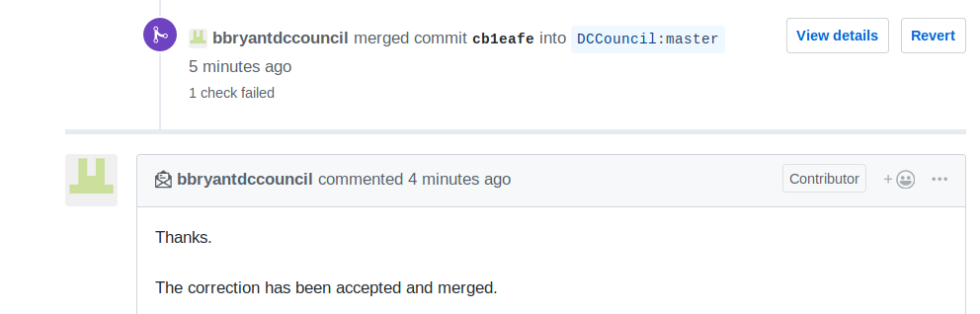

A few days later, the Council’s codification lawyer merged my pull request:

... and the DC Code website was automatically updated, showing what you’ll see on the page today:

This is a milestone in the advancement of open government and open legal publishing. No one should expect that editing the law on GitHub is going to become the new normal, however.

My edit wasn’t substantive. This sort of “technical correction,” as lawyers would call it, didn’t need to be passed by the Council and signed by the Mayor. I also happen to have expertise in this particular law, GitHub, XML, and the Council’s new publishing process created by the Open Law Library. So I knew what change to submit, and DC’s codification counsel was able to merge it with the click of a button. That’s not how lawmaking works, and GitHub’s pull-request feature isn’t going to replace public hearings, expert testimony, negotiations between stakeholders, votes by elected representatives, etc. — and it shouldn’t.

Yet Open Law Library’s new legal publishing process is groundbreaking.

The Open Law Library is changing how we change the law

The Code of the District of Columbia (the “DC Code”) is the compilation of laws enacted by our local legislative body, the Council of the District of Columbia. Each time the Council passes an act, it amends existing law—add a section, strike a semicolon, and so on. Those piecemeal changes in the act are then incorporated, one by one, into the Code in a process called codification. During codification, lawyers not only strike those semicolons, but they also make thoughtful decisions about how to arrange new parts of the law so that everything makes some logical sense all together.

The Council’s codification process has been overhauled in recent years. What was once a largely manual process of dissecting Word documents containing the acts and placing parts into other Word documents containing the organized DC Code, this workflow is becoming more and more automated by the Open Law Library, the Council’s new nonprofit codification contractor.

Open Law Library’s mission as a nonprofit is to make all laws as open and accessible as possible. The library’s strategy is to achieve openness by making openness pay off for governments: it uses open, machine-readable laws to build software tools that make codification faster and more accurate. The cool thing about this is that governments can benefit from using Open Law Library’s software even if open data isn’t their highest priority, but in the background they’ll still be publishing their laws in an open and accessible format—everybody wins.

Today, instead of authoring the DC Code in Word documents stored on a hard drive in a locked room in a basement, the Code is now stored in XML format in a place everyone can see—on the Web.

If you looked closely, you may have noticed that the screenshots above aren’t all showing the same document. The Open Law Library’s new technology transforms the XML file that stores DC Law 22–168 (the file I edited) into the website for DC Code § 1–1162.05c. The software changes the text of the citation from “the Freedom of Information Act” into “subchapter I of Chapter 5 of Title 2” and adds an HTML link based on the XML tag around the citation.

It’s full circle for me

I’m thrilled that the District has come so far in innovating legal publishing—partly because I helped put this all in motion. This transition began in 2013 when local civic hacker Tom MacWright, epic legal data liberator Carl Malamud, the Council’s own lawyer Dave Zvenyach, and I put the first full download of the District’s legal code online. Malamud bought a printed copy of the DC Code, digitized it, and mailed it around on USB thumb drives. After two hackathons and some funding from the Council, by 2014 we had converted the DC Code into XML and posted in unofficially on GitHub for anyone to use.

I wrote more about our efforts back in 2014, but putting the law online is an ongoing issue. Eighteen states and the District have now enacted Uniform Electronic Legal Material Acts (UELMA), which is driving adoption of modern legal publishing practices by the states.

But some states are resisting. Earlier this year, Malamud won a case against the state of Georgia which tried to prevent him from sharing electronic copies of the state’s legal code! And in DC, while the Council is making progress with the DC Code, other parts of DC law, including regulations, now lag behind.

Besides the District, several other jurisdictions are publishing their legal codes with official bulk XML downloads: the US federal government began publishing XML downloads for the Code of Federal Regulations in 2009 and the United States Code in 2013.

There are also dozens of private/nonprofit sector projects to create open legal data where it doesn’t exist officially elsewhere, such as CourtListener for the US courts, and my organization GovTrack.us did the same for bills before Congress until Congress itself began publishing open legislative data. And there have been many unofficial attempts to put legal codes on collaboration websites like GitHub (e.g., in Germany, France), and related efforts by Waldo Jaquith and the OpenGov Foundation on their State Decoded project in three states and three cities.

But the District appears to be the first jurisdiction to combine the two by putting its legal code on GitHub and accepting a change from a member of the public.

Why it matters

Publishing legal codes on GitHub is a real government innovation. It isn’t like the techno-solutionist blockchain nonsense that is in vogue lately. It’s the cherry on top of real work happening inside the DC government improving a process hundreds of years old:

- The Council is able to publish the law better and faster than ever before. With the District’s previous codification contractor, updates to the DC Code were published three times a year, and there could be a five-to-seven month delay in seeing the latest laws. But the Open Law Library has shortened the publication process to about a week after a law is enacted.

- It also means we’re all getting to see more of the actual law that governs us—not the law as it was months ago.

- The laws are now published on an easy-to-use, modern, searchable, mobile-friendly, and free website: https://code.dccouncil.us/dc/council/code/.

- This increases access to justice for District residents and lawyers at legal aid organizations who don’t have access to high-priced legal research tools.

I hope other jurisdictions learn from the District and move the law forward with the Open Law Library, and I especially hope that the District expands its use of Open Law Library tools to other aspects of DC law starting with the DC Municipal Regulations (DCMR).

Joshua Tauberer is a civic hacker based in the District of Columbia best known for founding GovTrack.us, which created the first comprehensive open data for legislation in the US Congress. He previously was a consultant for the DC Council, where he created the first data standards for the Council’s ongoing work to modernize the DC Code, and the US House of Representatives’s Office of the Law Revision Counsel, which publishes the United States Code. He is currently a contractor for GovReady PBC and a member of the DC Mayor’s Open Government Advisory Group.

reader comments

64