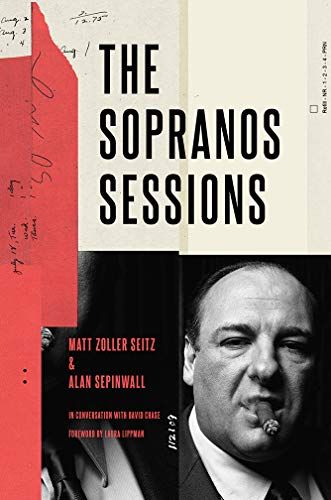

Twenty years ago today, HBO aired the first episode of a mobster show that would change television forever. Not since Twin Peaks 10 years prior had TV audiences seen such a revolutionary drama. And, at the time that The Sopranos aired, Alan Sepinwall and Matt Zoller Seitz—critics from New Jersey's The Star-Ledger—were among the first writers to document what would become a cultural phenomenon. Now, 20 years later, their book The Sopranos Sessions collects essays, recaps, and long-form interviews with series creator David Chase about every episode. Below is an excerpt from the book in which Seitz, Sepinwall, and Chase discuss the controversial scenes of violence in The Sopranos.

Matt Zoller Seitz: All the stuff related to Feech and Paulie’s battle over territory with the landscaping businesses reminded me of how almost every extremely violent scene in this show has an element of slapstick to it.

David Chase: Absolutely! I was just going to say that.

M: Do you have a particular aesthetic when it comes to violence?

D: For this show I do.

M: Can you talk about it more detail? I think this is important, because there were accusations that you were getting off on the violence, that it was sadistic and cruel. But at the heart of it, you’re saying it’s more Three Stooges or Laurel and Hardy?

D: It’s interesting you say that, because I am a huge Laurel and Hardy fan. They did a thing on The Sopranos at the Musum of Modern Art, and I was interviewed by Larry Kardish and he asked me about my influences. I said Laurel and Hardy, and I guess it’s probably still true! Terry Winter is a Three Stooges guy, and Terry is one of the best at depicting violence.

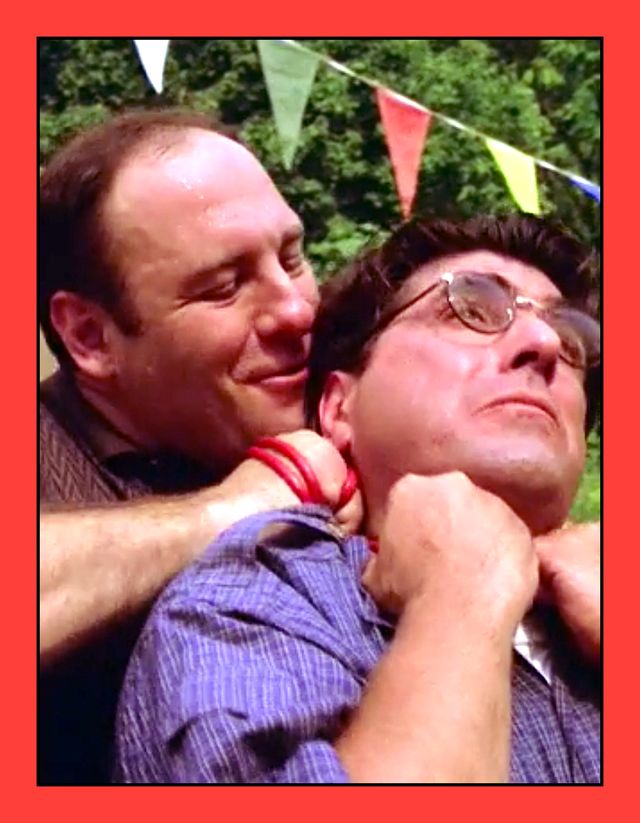

M: Even the emotionally intense violence that’s not supposed to be funny has elements of slapstick, like the fight between Tony and Ralphie resulting in Ralphie’s death. They use a frying pan and a can of bug spray, like a characters in a cartoon.

D: Ilene [Landress] used to tell me all the time that I should make a slapstick feature. But I don’t know that they work anymore.

M: I can’t deny that a lot of the violence is funny.

D: How did you feel about Lorraine Calluzzo being chased out of the living room with the towel snapping?

M: That was too much for me. It’s hard to describe why that was too much for me.

D: That’s why I asked you.

M: Maybe because I didn’t find her humiliation funny, but I felt like you wanted me to. Whereas Richie Aprile running over Beansie is not funny, and seemed like you didn’t want me to think it was.

Alan Sepinwall: About Lorraine Calluzzo: she’s styled in a very particular way, and there’s a scene outside Shea Stadium parking lot where Johnny complains to Tony, “All she ever wants is whack, whack this, whack that,” and at the time, there was some speculation that she was specifically modeled off of Linda Stasi, the TV critic at the New York Post who had written a screed at the end of season four about how the show wasn’t violent enough for her anymore.

D: I remember being really angry at it. I thought it was a stupid comment. What did happen before that was that [Stasi] came in to read for a part. I never should’ve agreed to it. She read, didn’t get the part, and then she turned negative after that.

A: I found in some of the archival Star-Ledger material a quote you gave me at the start of season five: “There was one woman writer back then who was saying, ‘Whack somebody! Whack somebody, for god’s sake!’ So this year, we decided to whack somebody who looks like her.”

D: Right! I’m glad I said it!

M: I want to get back to this slapstick thing. Certain types of screen violence are acceptable and other kinds are not. Some kinds are controversial and problematic, and others are not. Why?

D: I’m not sure. All I know is none of us want to see violence against an animal. A dog, a cat, whatever. It’s outré.

M: Why?

D: Because they’re really innocent, I guess. Same as a baby or a child. And . . . I guess maybe the reason a lot of the violence on this show seems funny is because of a notion that we’ve all done bad things, we’re all jerks in some way or another, but here you see somebody get their comeuppance. Of course I can only talk about it in The Sopranos. For instance, Beansie had it coming in some way. I don’t mean just with the Mob. For example, if we’d had Mr. Wegler fall down some stairs and break his collarbone, we’d all be hooting about that right now.

M: Why, because he’s a bit of a pretentious person?

D: He was.

M: That’s an interesting idea—that, to quote Clint Eastwood in Unforgiven, “We’ve all got it coming.”

D: Yeah, yeah. I don’t mean in Mob-speak, either.

M: You think we’ve all got it coming? In what sense do you mean? Cosmically?

D: You know what it is? We all have this image we want to portray, that we’re in control. Control is a big issue in human life. Falling down, or having violence arrayed against you, is a lack of control, and all your pretenses, your image—that all goes down the toilet, who you’re trying to project yourself as.

A: But some characters don’t suffer on camera. Arguably, the most memorable bit of violence in season five happens off-camera: Adriana crawls away from Silvio, he raises the gun, and you don’t see her death. Why did we not get to see that, yet you were happy to show us other stuff in detail?

D: Part of it was, I liked the whole image of her crawling through the leaves, and the sound it makes, and how autumn is so cozy, and you don’t see her killed for those reasons, aesthetic reasons having to do with the architecture of the shots.And then later on, when Carmela and Tony are sitting together in the woods, it’s a callback to that. But I really wonder why I didn’t show Adriana getting it. I’ve thought about it a lot, the fact that you don’t see her get shot. I guess it just felt wrong. It’s probably something that I didn’t want to see. I liked that character too much. She’d suffered enough. And she wasn’t pretentious. She was not a phony intellectual. She was just trusting, sobbing-prone. She was innocent.

M: She always wanted to believe the best of people.

D: She really did, and she fell into this trap of the FBI’s that wasn’t really her doing, and she didn’t even really understand it.

A: Did Edie, Jim, and Lorraine, as three of your more prominent actors, give you pushback on story ideas?

D: Edie, no. Lorraine, some. Jim, all the time.

A: What in particular did he tend to object to?

D: Brutality, I think.

A: Did he say why?

D: Because it was so dissonant with his own values. I could say, “Well, Jim was a big guy, an angry guy, and he was concerned about that. He didn’t want to be taken for a bully or a thug, even before the show.” It was for the obvious reasons: he didn’t like what the characters were doing and he didn’t want to portray that.

A: So what would you tell him?

D: We’d go around and around, I’d say this and he’d say that. It depended on the case. In the end, he’d always do it.

M: I watched a documentary about Jim. It included a part about just him acting. Working on the set, working with the lines, the blocking and so forth. There were snippets of behind-the-scenes footage of him getting frustrated, like if he felt like a scene wasn’t working for him, if he didn’t think he could play it or it just wasn’t right. You’d actually see him snap and go like, “Goddammit! This doesn’t work!”

D: He did that a lot.

A: The confrontation between Tony and Gloria, when they’re in her house and he picks her up—

D: That was a scene Jim objected to. That was an all-day sucker, to get him to do that.

M: Why didn’t he want to do it?

D: He just didn’t want to do that. And we don’t know what it’s like to have to pick up a woman and throw her. I mean, I hope you don’t know. He didn’t want to be seen that way, thought of that way—he probably didn’t want to experience it, because he has to go there to do it. It has to be believable, and he actually has to be doing it. He didn’t want to be thought of as a beast, you know?

M: I remember there were a lot of complaints during season three, because I heard them, about violence against women. That was the season not only with Tracee dying in “University,” but with Dr. Melfi’s rape in “Employee of the Month.” And also, related images like Silvio manhandling Tracee by the car in “University.”

A: And Ralphie laughing while he’s doing it.

M: I don’t think we’d ever seen Silvio commit violence before. There was this sense that the characters were . . .

D: Uncaged.

M: Yeah. They were animals toward women, they were brutal. It was as big a shock to the system as hearing the unbridled racism in the back half of season one.

D: I’m only saying, the only thing I ever read about it at that time was feminist complaints about the death of Tracee. I never heard anything about Silvio or any of that stuff. It’s interesting that they all got clotted in that one season, though. Melfi’s rape, that was the same season?

A: She’s raped in episode four, Tracee dies in episode six. And in between, Burt Young coughs himself to death. It was a happy stretch of the show. [Laughs]

M: It was. I remember having conversations with people at the Star-Ledger about the level of violence on the show.

D: Really?

M: Yes, and the blunt sexual humiliation and violence, the stuff with Tracee, the rape. There was one writer Alan and I both knew who said, “I can’t watch the show anymore, it’s become pornography.” Everybody’s breaking point is different with regard to that.

D: But here’s what I don’t understand: If Melfi’s rape had not happened in tandem with Tracee . . . how would it have been outré to do a story about rape? Because it was so graphic?

A: I think, to a degree, people were protective of Dr. Melfi. Like, she’s this “strong woman” in the context of the show, and here, she’s brought terribly low.

D: Oh, I see.

M: Here’s what I was trying to get at with these violence questions: Was there ever any frustration on your part, or the part of the other writers, that the audience loved these gangsters so much?

D: Yes.

M: Was there any element in this stuff we’re talking about—violence against women, racism, escalating levels of brutality, the sadism of characters like Ralphie—where this was your response to these viewers? Like, “You can’t like these guys! Goddammit, what’s wrong with you?”

D: Yes.

M: So you were trying to answer the question, “What do we have to do to make you people not like these guys?”

D: Yeah—to make you see what this show is about. It’s about people who’ve made a deal with the devil, starting with the head guy. It’s about evil. I was surprised by how hard it was get people to see that. I mean, you only have me to trust about this, but I can tell you, there would’ve been a limit as to how far we’d have gone to make sure people got that.

M: In “University,” the show parallels the tragedy of Tracee and her death at the hands of Ralphie with Meadow and Noah. What was the thinking of intertwining those two stories?

D: I think it was just to compare the upbringing of Meadow with the upbringing of Tracee, like Tracee’s mother burning her hand on a stove. It went back to this TV movie I had made called Off the Minnesota Strip,10 about teenage hookers from Minneapolis. I remember when I went out there, I began to see how to some that was about class. I wanted to compare Meadow’s soft upbringing with Tracee’s. Meadow thought her life was full of drama, but Tracee’s was really full of drama. I think I included Noah because he was such a soft guy, a decent man.

M: I wonder if one of Tony’s main sources of guilt over Tracee is that he didn’t want to hear about her problems.

D: Tony never wants to hear about people’s problems, and that was a big one. I think he was aware, on some level, that he had one kind of daughter, and then there were lots of other daughters running around this country—strippers, prostitutes, the women that he preys on.

A: After Tracee dies, Tony attacks Ralphie and Ralphie screams out, “I’m a made guy! You can’t do that!” We’ve seen Tony do that to made guys before. He stapled Mikey, he’s done a number of things. Did you have a sense of what the rules were and weren’t for somebody like Tony?

D: It’s all horseshit. [Laughs] Ralphie was citing horseshit, and he knew it. It’s all about money. Didn’t we say there were monetary problems because they’d fallen out? That’s the reason Tony has to make good with him. Another deal with the devil.

A: Rosalie, despite being a Mob wife, is one of the better human beings on the show.

D: She is, yes. She was good.

M: And Ralphie really is the devil.

D: We did that whole scene [in season four’s “Whoever Did This”] with “Sympathy for the Devil,” where we quoted the lyrics, in the hospital and in the scene with the priest. That was a lot of fun.

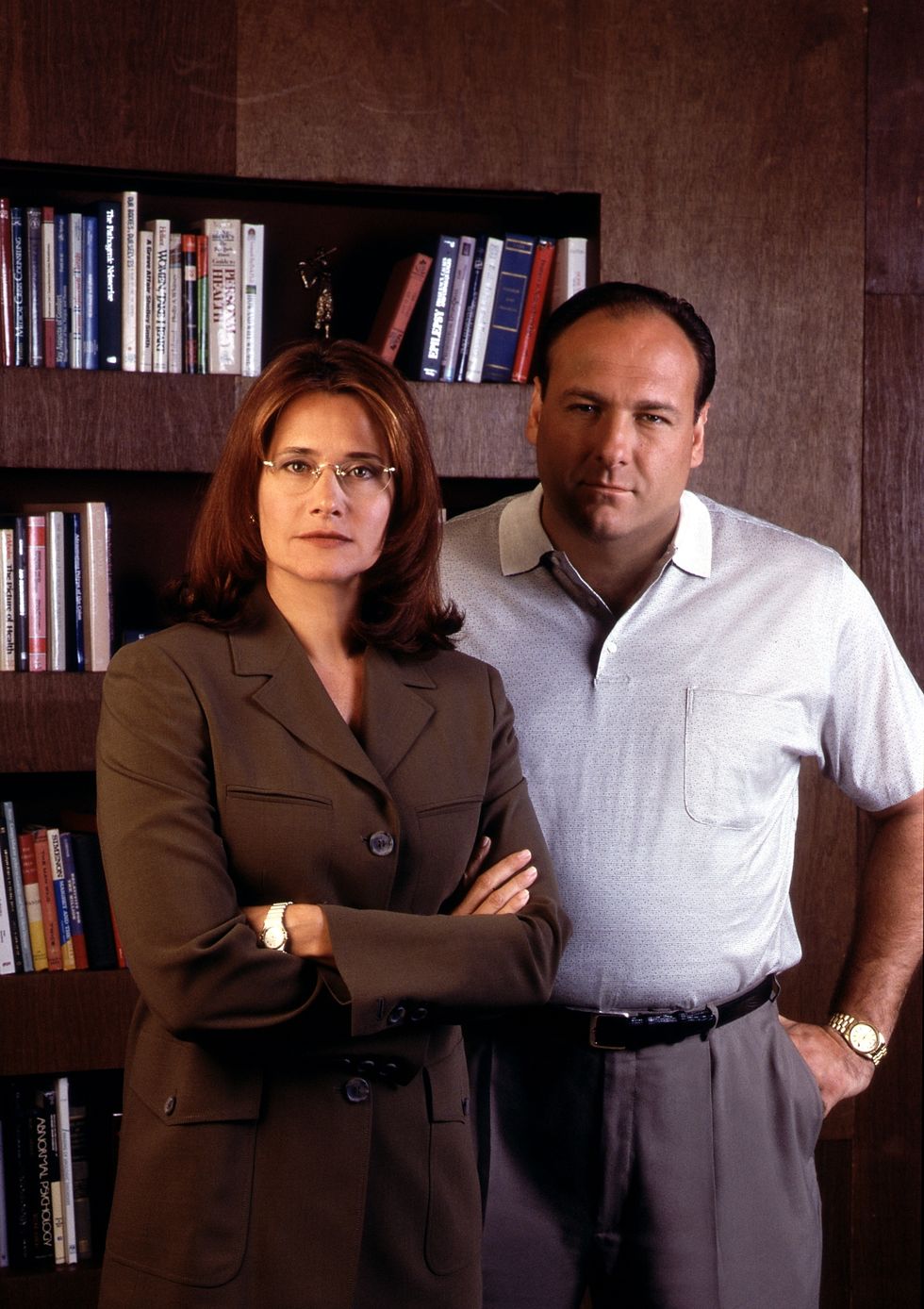

A: By the time we get to “Employee of the Month,” Melfi is looking to offload Tony to another therapist. Was there any concern in your mind of, “If she solves the panic attacks, why does he keep going to see her, and how do we maintain this relationship over the life of the show?”

D: No. I thought by that time, he was in it. He was hooked on therapy, like so many people.

M: What kind of progress do you think Tony thought he was making?

D: “I bought my wife a nice fur hat, I’m not yelling as much, I’m a better listener.” I’m sure he thought all that. [Laughs]

M: But not the deeper stuff that Melfi wants him to think about.

D: No. These things would pertain to the deeper stuff, but if you’re a better listener,ergo, you’re a better person.

M: You have a lot of characters on this show who are in therapy, or at least have occasional visits there, or who speak in the language of self-help. Sometimes even Paulie!

D: That stuff is all around, that’s why. It’s all over the place. And Christopher’s “I gotta be a better friend to myself.” [Laughs] But it’s always self-justifying.

A: Melfi sometimes turns out to be a better consigliere to Tony than Silvio. She’ll give him advice without realizing its context, like when she tells him to read The Art of War. How complicit do you feel she actually was?

D: Not complicit. Or at least not consciously complicit.

A: You talked before about how she made a deal with the devil to continue treating him.

D: That’s the whole thing: “This is my patient.” When have you ever heard of a therapist yell at a client and say, “What are you doing? That’s terrible! You shouldn’t do that!” When have you ever heard them go that far? I think to therapists, the parents are automatically at fault—which they are! Everything results from parents’ mistakes. But they can’t help it most of the time.

M: A lot of time the parents are just repeating the mistakes that were made [with] them.

Adapted excerpt from the new book The Sopranos Sessions by Matt Zoller Seitz and Alan Sepinwall published by Abrams Press; © 2019 Matt Zoller Seitz and Alan Sepinwall