What Moon Craters Can Tell Us About Earth, and Our Solar System

Asteroid impacts have a bad reputation here on Earth — it's the dinosaurs' signature public relations victory — but it's the moon that really bears the scars of living in our messy neighborhood.

That's because Earth has an arsenal of forces that slowly wear away the craters left behind by impacts. And that's frustrating for scientists who want to better understand the debris hurtling around our solar system. So a new study uses the pockmarked lunar surface to trace the history of things smashing into both our moon and Earth, finding signs that our neighborhood got a lot messier about 290 million years ago.

"It's a cool study that talks about our dynamic solar system and it's good that it's out there," Nicolle Zellner, a physicist at Albion College in Michigan who was not involved in the new research, told Space.com. "It'll get people thinking and testing it, so that's exciting." [How the Moon Formed: 5 Wild Lunar Theories]

Earth and the moon are close enough on the solar system scale that stray asteroids should crash into each at about the same frequency. (Earth may attract a few extra with its stronger gravity, and Earth likely suffers more hits because of its larger surface area — but in terms of impact per square mile, they should be clocking in about the same.)

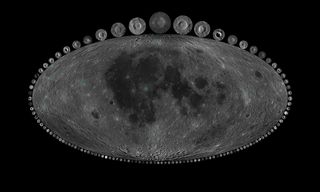

Scientists have identified only about 180 impact craters here on Earth, as opposed to hundreds of thousands of lunar impact craters. Earth wipes them away with winds and rainfall, oceans and plate tectonics. "The moon is perfect for studying craters," Sara Mazrouei, a planetary scientist who led the new research during her doctoral studies at the University of Toronto, told Space.com. "Everything stays there."

But in order to trace the history of impacts, scientists needed to not just identify craters, but also estimate their ages. And that's much harder on the moon than on Earth, since geologists can't currently sample lunar craters directly.

So the team behind the new research settled on what may be a surprising measurement: how well nearby rocks retain heat during the long, cold lunar night. That might seem like an awfully random measurement. But when a large impactor strikes the moon, it scoops out a crater and litters the surrounding landscape with boulders sourced from that material. Over time, those rocks are struck by smaller impactors that break them into smaller and smaller rocks, which eventually become dusty regolith, so the team argued that older craters would be surrounded by finer rocks and younger craters by larger ones.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Then, when that landscape transitions from a 14-day lunar day to a 14-day lunar night, it changes temperature at different rates. "The idea is that big rocks can hold heat throughout the night, whereas that regolith or sand loses heat," Mazrouei said. "As craters get older, they become less rocky." In turn, they cool off faster.

So Mazrouei and her colleagues looked at thermal imaging data from an instrument called the Diviner on board NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, which has been circling the moon since 2009. The team identified 111 individual craters that they knew were less than 1 billion years old, analyzed their heat signatures and, using a model of how quickly lunar boulders disintegrate, estimated their age.

The result showed an intriguing pattern: a spike in impact rates about 290 million years ago, when cratering rates appear to have more than doubled. That would suggest something significant changed in our solar system around then — perhaps, the team proposes, a large space rock in the asteroid belt breaking up and wandering closer to Earth and the moon. And comparing the craters we do know about here on Earth to their results, the team sees similar patterns, suggesting scientists have found a pretty representative, if small, collection of craters.

Not everyone is convinced. "The results are intriguing, but I think that the actual support for these conclusions is pretty weak," Jay Melosh, a planetary scientist at Purdue University who wasn't involved in the new research, told Space.com. In particular, he's not sold on the boulder- disintegration model they used — he thinks it doesn't properly account for how that process speeds up as rocks get smaller. And he doesn't see enough Earth craters to support solid statistical analyses; he worries that they're working from too small a sample size. [The Moon: 10 Surprising Lunar Facts]

"That doesn't mean it's wrong, but it also doesn't mean that it's right — we just really don't know," Melosh said. "This is a noble attempt to go just a little bit farther than the data support."

Zellner understands how difficult studying lunar craters can be: she's worked with the droplets of glass created by impacts and carried back to Earth in samples gathered by the Apollo astronauts. But dating that glass is still a challenge even with lab technology, and the samples all come from a small patch of the moon's surface. Orbiter data puts scientists at more of a distance, but covers the entire lunar surface — neither method is perfect.

"We're doing the best we can with what we have now," Zellner said. "This is science, right? We put ideas out there, and then we find ways to test those ideas, and the idea either stands the test of time or it doesn't."

And all three scientists offered compelling reasons why doing the work to figure out the moon's impact history is worthwhile. First, of course, there's the self-interested approach: Earth craters can come with some unpleasant side effects.

"Everybody is interested in the cratering rate on Earth because we don't want to end up like the dinosaurs," Melosh said. The catastrophic aftermath of the impact wiped out a staggering three out of four species alive at the time, although the extinctions left plenty of room for our own mammalian ancestors to thrive. "We should thank our lucky meteorite, but it was pretty bad for everybody else on the planet." Learn enough about impacts, the theory goes, and we may be able to save our own skins the next time around.

For Zellner, there's a more exotic appeal as well: Learning more about our own solar system could help scientists understand not just our own neighborhood, but also the processes that have shaped the alien solar systems that scientists keep discovering.

Mazrouei sees the work as an example of how different solar system bodies can shed light on each other. One of her co-authors is already looking forward to how the BepiColombo mission to Mercury, armed with an instrument much like that at the moon now, will be able to add another dimension to cratering studies.

Earth is great to live on, but scientists can't piece together its past from home. It takes studying the moon and its pristinely cratered surface to understand what our planet has been through, Mazrouei said. "We get to detangle a lot of Earth's history as well."

The new research is described in a paper published today (Jan. 17) in the journal Science.

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us @Spacedotcom and Facebook. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.