You’d think it would be easier to run down a mountain than to run up it. And sure, if you’re talking about gasping for air and feeling your heart pounding, that’s true.

But as far as your legs are concerned, running downhill for a long period of time is one of the cruelest punishments you can inflict. The eccentric muscle contractions (your quadriceps and calf muscles are trying to shorten but are being forced to lengthen each time your foot hits the ground) cause significant microscopic damage to your muscle fibers, including fatigue and eventually pain, and then delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS) in the days that follow. In fact, downhill running is commonly used in labs to study DOMS.

A pair of recent papers, one in the European Journal of Applied Physiology and the other in the journal Sports Medicine, from researchers in France and Canada led by Guillaume Millet of the University of Calgary, take a deep dive into the fatigue associated with both downhill and uphill running—and beyond the physiology, they offer some interesting practical advice.

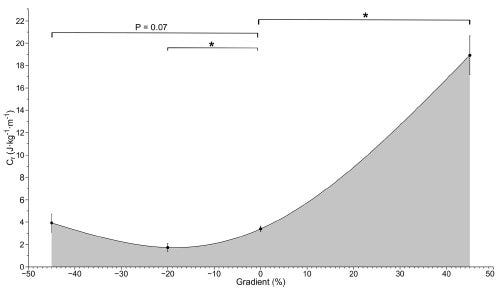

For starters, here’s an estimate of the energy cost of running at various slopes, drawing on a 2002 paper:

The interesting point: Yes, you use less energy running downhill when the slope is less than about 20 percent. Beyond that, though, each step requires more braking and provides less acceleration, so you start burning more energy again.

So how do you maximize the benefits of running downhill while minimizing the harm? In the EJAP paper, Millet and his colleagues consider the following strategies:

- Increase your cadence: Shortening your stride by increasing stride frequency by 8 percent reduced muscle damage in one study.

- Vary your foot strike: There’s a bit of evidence that landing on your toes on a downhill puts extra strain on muscles compared to landing on your heels, resulting in greater muscle damage. That said, a more useful strategy to keep in mind is to mix things up to vary the load on different muscle groups, by switching between different foot-strike patterns. That happens naturally on uneven trails, but might involve a deliberate decision on smoother downhills.

- Lose weight: Not a big surprise, but being heavier accentuates the damage from running downhill. If you figure out a reliable way of losing weight, you could also market it to the general public and become a millionaire.

- Train for it: As the authors note: “Among all strategies to attenuate the negative effects of downhill running, training remains the best option. Several studies demonstrated that a previous bout of eccentric exercise produces a protective adaptation, such that, after a subsequent bout of similar exercise (the so-called ‘repeated bout effect’), symptoms of muscle damage and strength loss are alleviated up to 10 weeks after exercise.”

This is the big one. If you’re planning a race that includes substantial downhill, make sure you do some significant downhill running in training—significant enough that it makes you sore. If you live on the prairies and there are no hills around, find a treadmill and set it to run downhill.

I don’t know exactly how much downhill running is needed, or how often, to maximize the benefits (though the fact that some benefits can last as long as 10 weeks is certainly impressive). It would depend, in part, on how grueling the course you’re planning to race is. You don’t want to make yourself so sore that you miss a week of training—but I suspect that it’s a good idea to do enough that you’re at least a bit sore the next day, and repeat that process several times.

***

Discuss this post on the Sweat Science Facebook page or on Twitter, get the latest posts via e-mail digest, and check out the Sweat Science book!